Author Affiliations

Abstract

The Murraya paniculata (MP) methanolic extracts were subjected to Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis, a NO assay for measuring antioxidant activity, and an estimate of significant phytochemicals. When compared to conventional ascorbic acid, the presence of abundant polyphenols, flavonoids, and tannins exhibits good antioxidant activity (50.88 %) (53.87 %). The principal 13 active phytochemicals in the crude extract are further confirmed by the LC/MS analysis. To identify the most powerful phytochemicals, these compounds were molecularly docked on the human estrogen receptor (a target protein for breast cancer). In this investigation, the 5,7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl) coumarin exhibits good drug-like qualities and a greater binding interaction (-30.3502 Kcal/mol) than the conventional 5-flurourasil (-25.3186 Kcal/mol). We also use molecular dynamics modeling to confirm the protein stability, Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), and Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) of this phytochemical with the target. Finally, we discovered seven phytochemicals with powerful anti-breast cancer properties.

Keywords

Murraya paniculata, Antioxidant, Molecular docking, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity, Breast cancer.

Introduction

The oldest form of healthcare still in use today is herbal medicine. Since natural products make up more than half of today’s medications, they play a critical role in the expansion of the pharmaceutical business. Plants release phytochemicals, which they synthesize in response to environmental factors or disease. Although they are not required for plant metabolism, they aid in the treatment of some illnesses in humans. To support their use as possible sources of antimicrobial agents, plant materials must first undergo a thorough investigation of their composition and biological activity.[1] The development of antibiotic-resistant microorganisms has accelerated the quest for novel antibacterial drugs. The incidence of several drug-resistant diseases has increased because of widespread antibiotic misuse or incorrect antibiotic management, which has caused many antibiotics to lose their effectiveness against some microorganisms.[2]

The Rutaceae family includes MP, a widespread plant in the Indian subcontinent also known as orange jasmine, Honeybush, or Kamini.[3] From the Malesian region to northeastern Australia and New Caledonia, as well as in India, Bangladesh, tropical Sri Lanka, Myanmar, southern China, Taiwan, Thailand, and Caledonia, this tree is widespread throughout Asia—a small tree with a spreading crown and a short stem. Alternating, impercipient leaves are 10–17 cm long; leaflets are normally 3–7 cm long; they are oblong, elliptic–lanceolate, or rhomboid; glossy above; gland-dotted; and have a rounded or cuneate base. The leaves are astringent and stimulant in nature. They are used successfully to treat dysentery and diarrhoea in several countries.[4] It is rumoured that these leaves can be used to make a paste with mustard oil to cure joint pain. The leaves also have anti-diabetic, anti-nociceptive, anti-inflammatory, anti-diarrheal, anti-oxytocic, and anti-fertility properties in vitro.[5,6]

Compounds derived from herbal treatments have long been thought of as a starting point for the development of medications, especially anticancer drugs. Since they have low adverse effects, plants and other natural resources are exploited to make anti-cancer medications.[7,8] Research on medicinal plants has increased recently to reduce drug toxicity and resistance in the treatment of cancer. Numerous plants have been shown to be free of harmful side effects and possess anticancer qualities.[9] Some herbal medicines have been shown to have anticancer properties. Numerous plant-derived anticancer compounds, including those that inhibit breast cancer [10-12], have been discovered using intensive screening procedures.[4]

In this study, the identical plant MP was utilized to assess antioxidant activity and phytochemical analyses. Furthermore, using LC/MS, molecular docking, molecular dynamics, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) analysis, we discovered that MP’s powerful phytochemicals have anti-breast cancer action.

Methodology

Plant materials and preparation of plant extract: MP dried leaf powder was purchased from Siddha and Ayurvedic stores. The 50 g of powder from each leaf was extracted using a Soxhlet method with 98 % methanol and filtered through Whatman filter paper. For additional photochemical screening, antioxidant activity testing, and LC-MS analysis, the resulting MP filtrates were concentrated under vacuum in a rotatory evaporator at 40°C and kept at 4°C.

Preliminary phytochemical screening analysis: MP aqueous extract was subjected to preliminary phytochemical screening using the techniques described to look for alkaloids, flavonoids, polysaccharides, saponins, phenols, tannins, terpenoids, proteins, cardiac glycosides, and steroids.[13]

Nitric Oxide (NO) free radical scavenging assay: At physiological pH, sodium nitroprusside creates nitric oxide in an aqueous solution, which then interacts with oxygen to create nitrite ions, which may be seen at 550 nm on a spectrophotometer. Chemicals and reagents: sodium nitroprusside, phosphate buffer, 0.1 % N 1-naphthyl ethylenediamine hydrochloride, and five mM Griess reagent (1 % sulphonyl amide) (pH 7.4). The plant extract was dissolved in methanol for this measurement. Different quantities (100-500 g/ml) of methanol extract were incubated for three hours at 29°C with sodium nitroprusside (5 mM) in standard phosphate buffer saline (0.025 m, pH 7.4). An equivalent amount of buffer was used in a control experiment that was run without the test substances as a blank. After three hours of incubation, the samples were diluted with 1 ml of Griess reagents. At 550 nm on a spectrophotometer, the absorbance of the color formed during the diazotization of nitrite with sulphanilamide and its subsequent coupling with naphthyl ethylenediamine hydrochloride was detected. The same procedure was carried out using ascorbic acid, a standard, as opposed to the methanol extract. A formula was used to determine the % inhibition in contrast to the standard, and a graph was drawn as a result.

Formula: % inhibition = (%) = ((A-B)/A) X 100

A = Optical density of the blank, B = Optical density of the sample

LC-MS studies: A Mariner Bio spectrometer with a binary pump was used for the LC-MS analysis to evaluate the chemical components of the methanol extracts of MP.

In silico study: Molecular docking study on MP phytochemicals as anti-breast cancer activity.

In the current work, Auto Dock Vina, Swiss ADME, and Schrodinger’s Desmond module software were used to conduct in silico molecular docking ADMET toxicity investigations and molecular dynamics simulation.

Preparation for protein: For this investigation, a crystal structure with a resolution of 1.90 of the human estrogen receptor alpha ligand-binding domain in combination with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (PDB ID: 3ERT) was used. By applying the CHARM forcefield and the Forcefield algorithm to add hydrogens to the 3ERT protein, the protein energy was reduced. We applied the previously established molecular docking study parameters.[14]

Ligand preparation: The active MP molecules (1,3-Pentadiene, 5,7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl) coumarin, 7,8-Methoxycoumarin, Auraptene, Coumarin, Coumurrayin, Glibenclamide STD, Methyl 2,5-dihydroxycinnamate, Methyl 4-hydroxycinnamate, murralongin, murrayatin, Omphamur The list of MP main active phytochemicals was compiled from a variety of sources.[15]

Docking study: To identify the protein-ligand complex’s most prevalent structure, a molecular docking analysis was carried out. To better understand the structural underpinnings of these target proteins, AutoDock Vina software was employed in this molecular docking investigation to evaluate structural complexes of the 3ERT with collected molecules as well as conventional chemicals. Different binding processes between the ligands and these target proteins were examined inside the (CHARMm-based DOCKER) technique. To supply a complete ligand, the method makes use of CHARMm power fields. Utilizing binding energy, interaction energy, hydrogen bonds, binding energies, protein energy, and ligand-protein complex energy, the ligand binding affinity was estimated. Negative numbers are used to represent energy. More negative value energy is produced because of the ligands’ increased affinity for the target protein.

ADMET toxicity analysis: In drug development and environmental hazard assessment, it is essential to predict the ADMET profile for drug candidates and environmental pollutants. To categorize the likely harmful effects of these substances on humans, the ADMET properties of the filtered compounds were estimated using SWISSADME software. Included are the characteristics of solubility, absorption, Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB), Human Intestinal Absorption (HIA), ADMET, and risks. The absorption levels of the HIA model describe the 95 % and 99 % confidence ellipses in the ADMET PSA 2D, ADMET alogP98 aircraft.[16]

Molecular dynamics simulation: The MD simulation was performed using Schrodinger’s Desmond module. To control Crystal, add water, the finest phytochemicals, and using the System Builder tool, human estrogen receptor structures were placed in the orthorhombic box with a buffer distance of 10, and a water model was created using single point charge (SPC). To neutralize the systems, Sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl-) ions were added until a concentration of 0.15 M was reached. Using OPLS3 force field settings as the default protocol associated with Desmond, the constructed solvated system was minimized and relaxed prior to performing the simulation. At 300 K and 1.013 bar pressure, the MD simulation was run using an isothermal isobaric ensemble (NPT). During a 250-picosecond simulation, 1000 frames were recorded to the trajectory. Finally, the Simulation Interaction Diagram (SID) tool was used to investigate the MD simulation track.[17]

Result & Discussion

Phytochemical screening analysis: Alkaloids, flavonoids, carbohydrates, saponins, phenols, tannins, terpenoids, proteins, cardiac glycosides, and steroids were found in the phytochemical analysis of methanol extracts of MP (Table 1). Checking the extract’s phytochemical composition for alkaloids, flavonoids, phenolic chemicals, and tannins. Metabolites are crucial to the health of the plant. Alkaloids are present in plant materials and are antibacterial, antiseptic, and antimalarial. Flavonoids may have anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, anti-cancerous, and anti-allergenic effects. The plant materials contain phenolic components and saponins that have immunomodulatory, antibacterial, and antifungal effects. The extracts’ tannin content can be used to quicken the healing of wounds and inflamed mucous membranes. Finally, the presence of these phytochemicals demonstrates the therapeutic effectiveness of MP leaf extracts.

| S.No. | Phytoconstituents | Methanol | Ethanol | Ethyl acetate | Acetone | Petroleum ether |

| 1 | Alkaloids | – | – | + | – | + |

| 2 | Flavonoids | + | + | + | + | – |

| 3 | Carbohydrates | – | + | – | – | – |

| 4 | Saponins | + | + | + | + | + |

| 5 | Phenols | + | + | + | – | – |

| 6 | Tannins | – | + | – | – | – |

| 7 | Terpenoids | + | – | – | + | + |

| 8 | Proteins | + | – | – | – | – |

| 9 | Cardiac Glycosides | – | + | + | – | – |

| 10 | Steroids | – | – | – | – | – |

Table 1: Qualitative phytochemical screening of MP leaf extract

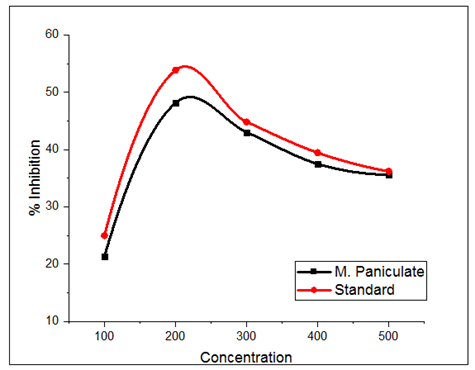

NO assay: NO is a pleiotropic inhibitor of physiological functions, including platelet aggregation inhibition, neuronal signalling, smooth muscle relaxation, and cell-mediated toxicity regulation. Along with reactive oxygen species, NO has also been connected to cancer, pathological diseases, and inflammation. It is believed that NO, a free-radical moiety that is present in many tissues and organ systems, plays a significant part in neuromodulation.[18]

MP has been shown to contain several phytochemicals, some of which are significant contributors to antioxidative action, in addition to triterpenoids and essential oils. The inhibitory value of MP leaf extracts is shown in Table 2. Figure 1 illustrates how MP extracts can neutralize NO radicals and ascorbic acid. The maximal activity of all the plant extracts in methanol was 50.88 % at 200 g/ml, while ascorbic acid showed a 53.87 % inhibition.

The results show that the MP plant’s methanol extracts include a variety of bioactive substances with antioxidant potential. The plant extract might help to stop or slow the development of disorders linked to oxidative stress. It might contribute to the creation of newer, stronger natural antioxidants. The methanol extracts of MP demonstrated significant antioxidant activity when compared to ascorbic acid. The results of this study suggest that MP may be a potential source of natural antioxidants that may be helpful as therapeutic agents in preventing or slowing the development of oxidative stress-related degenerative illnesses. These discoveries might help scientists and pharmaceutical firms create effective medicines to address conditions brought on by oxidative stress.

| Conc. µg/ml | MP | Standard |

| % of Inhibition | ||

| 100 | 21.342 | 24.996 |

| 200 | 50.88 | 53.874 |

| 300 | 43.040 | 44.827 |

| 400 | 37.502 | 39.451 |

| 500 | 35.618 | 36.205 |

Table 2: Inhibition efficiency of methanolic leaf extracts of MP (NO Assay)

Figure 1: NO scavenging assay of MP and ascorbic acid

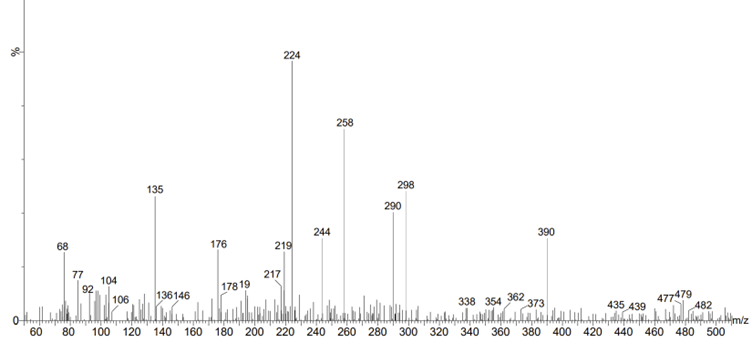

LC-MS analysis of MP: Due to the highly diverse biochemistry of plants, which includes many semi-polar chemicals and important secondary metabolite groups that can best be separated and detected by LC-MS techniques, LC-MS-based approaches are anticipated to be particularly important in plants. Several molecular ion peaks were found by LC-MS analysis of methanol extracts of MP (shown in Figure 2 and Table 3). A previously reported literature review validated the phytochemicals’ reported LC-MS molecular weight.[19] Table 3 contains a list of the candidates’ mass (m/z) and the resulting molecular weight spectrum for MP. To find the powerful phytochemicals with anti-breast cancer activity, these phytochemicals were subjected to additional in silico analysis.

Figure 2: LC-MS analysis of the methanolic extract of the MP

| S. No | Phytochemicals | Molecular weight |

| 1. | 1,3-Pentadiene | 68.12 |

| 2. | Coumarin | 146.14 |

| 3. | 7-Methoxycoumarin | 176.17 |

| 4. | Methyl 4-hydroxycinnamate | 178.18 |

| 5. | Methyl 2,5-dihydroxycinnamate | 194.18 |

| 6. | Coumurrayin | 224.31 |

| 7. | Osthol | 244.28 |

| 8. | Murralongin | 258.26 |

| 9. | 5,7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl)coumarin | 290.31 |

| 10. | Auraptene | 298.44 |

| 11. | Scopolin | 354.31 |

| 12. | Murrayatin | 362.4 |

| 13. | Omphamurrayone | 390.40 |

Table 3: LC-MS analysis of the MP

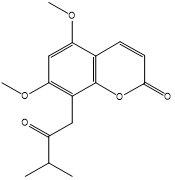

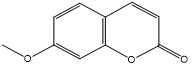

Molecular docking studies: The molecular docking study examined the anti-breast cancer effect of the 13 primary phytochemicals that were extracted from MP by blocking the human estrogen receptor protein. Table 4 provides a summary of the phytochemical structures found in MP. Table 5 provides a list of these phytochemicals’ binding energies. In this section, 3D and 2D figures are used to explain the most effective phytochemicals in comparison to standard medicine.

| S. No | Phytochemicals | Structure |

| 1. | 1,3-Pentadiene | |

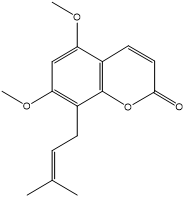

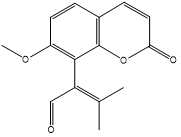

| 2. | 5,7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl) coumarin |  |

| 3. | 7-Methoxycoumarin |  |

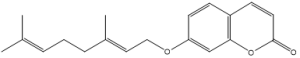

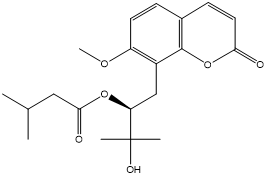

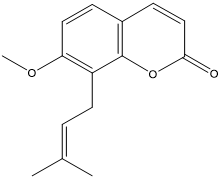

| 4. | Auraptene |  |

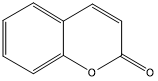

| 5. | Coumarin |  |

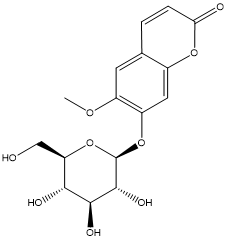

| 6. | Coumurrayin |  |

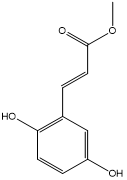

| 7. | Methyl 2,5-dihydroxycinnamate |  |

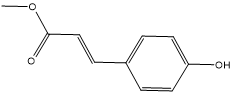

| 8. | Methyl 4-hydroxycinnamate |  |

| 9. | Murralongin |  |

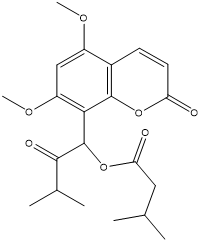

| 10. | Murrayatin |  |

| 11. | Omphamurrayone |  |

| 12. | Osthol |  |

| 13. | Scopolin |  |

Table 4: List of the major active phytochemicals of MP

| Phytochemicals | Binding energy |

| 5_7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl) coumarin | -35.2403 |

| Methyl_4-hydroxycinnamate | -30.3502 |

| Methyl_2_5-dihydroxycinnamate | -29.3661 |

| Murrayatin | -28.8854 |

| 7-Methoxycoumarin | -27.2899 |

| Omphamurrayone | -26.5787 |

| Coumarin | -25.7939 |

| 5-fluorouracil (Standard drug) | -25.3186 |

| Coumurrayin | -8.66125 |

| Osthol | -6.38308 |

| 1_3-Pentadiene | -4.74112 |

| Murralongin | -3.59922 |

| Scopolin | -3.3544 |

| Auraptene | -11.318 |

Table 5: Docking energy of phytochemicals of MP

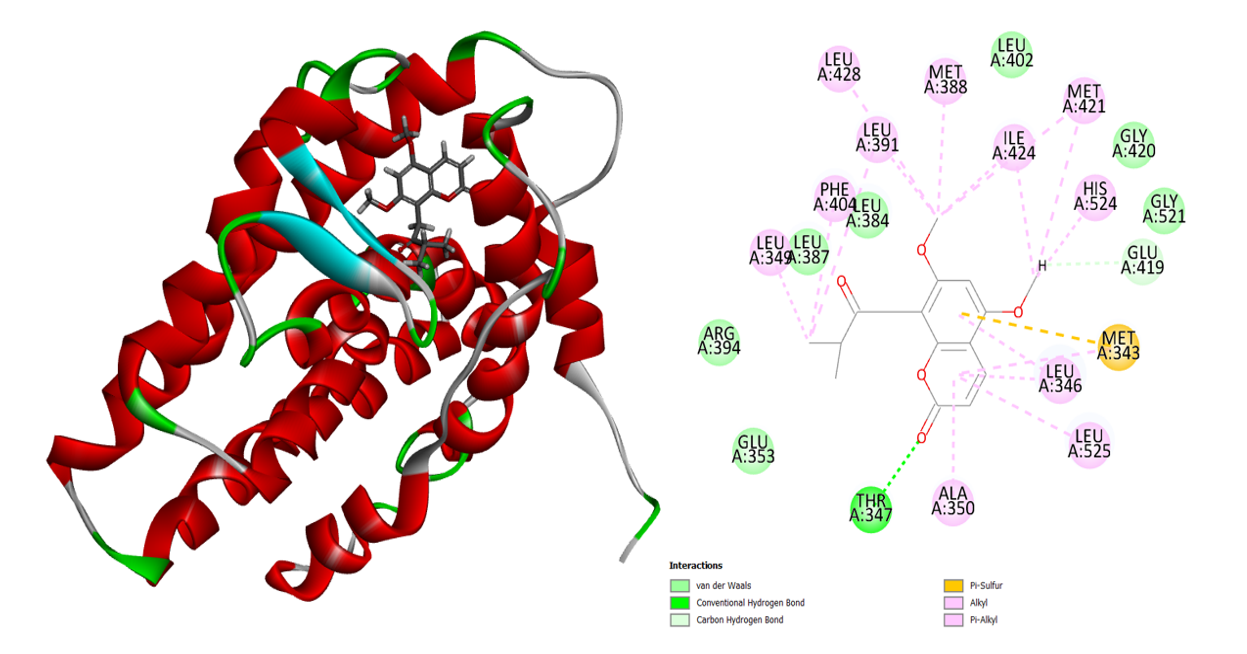

The plant from MP, 5,7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl) coumarin, exhibits a greater binding affinity to the human estrogen receptor. The 5,7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl) coumarin has a binding energy of -35.2403 Kcal/mol. The ketone group of this molecule interacts strongly with the amino acid Thr 347 to produce one H-bond (Figure 3). Most of the aromatic and alkyl groups in the 5,7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl) coumarin molecule engage with the human estrogen receptor’s active site through alkyl and Pi-alkyl interactions. Van der Waals interaction involves the other active site residues.

Figure 3: 3D and 2D interaction of the 5,7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl) coumarin in the active site of the human estrogen receptor

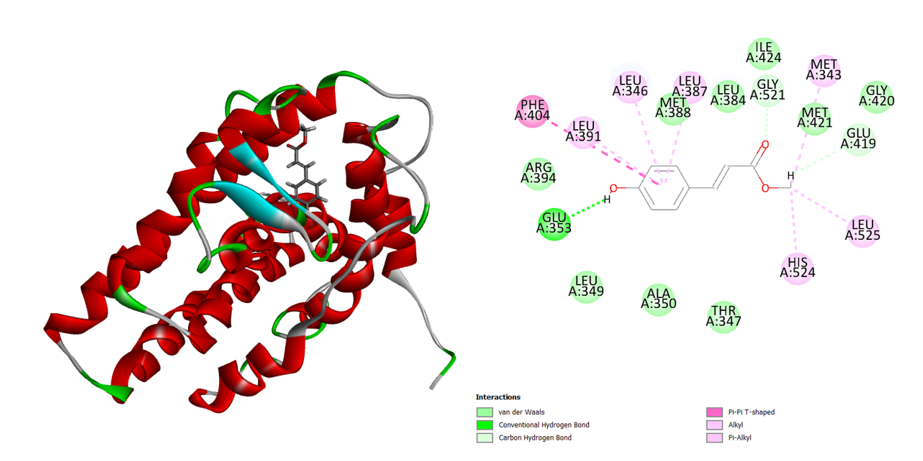

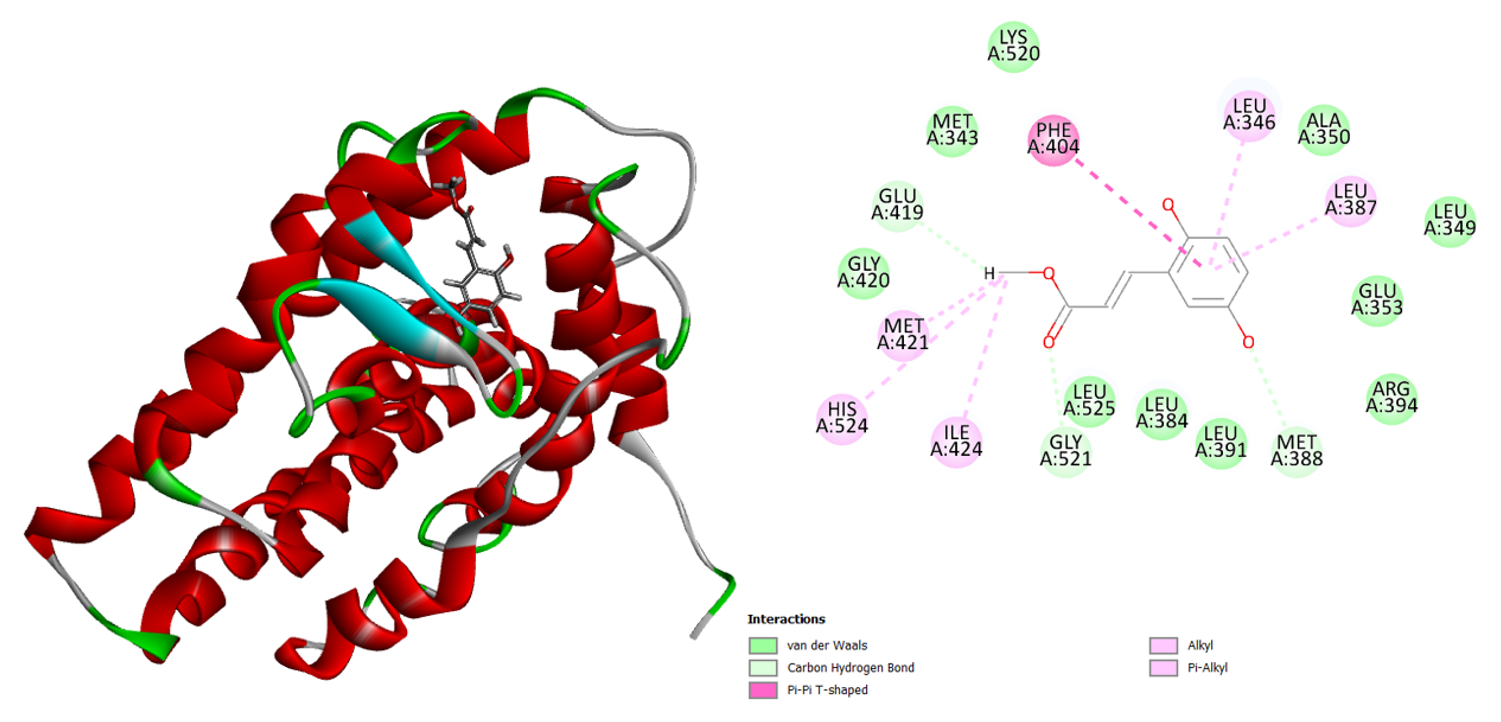

Within the active site, the methyl 4-hydroxycinnamate exhibits excellent binding contact. Methyl 4-hydroxycinnamate’s -OH group interacts with the amino acid Glu 353 to generate a potent H-bond. The Phe 404 amino acid interacts in a Pi-Pi T shape with the aromatic benzene molecule. Leu 525, His 524, and Met 343 amino acids were affected by the other methoxy molecule through alkyl interactions (Figure 4). Van de Waals contact with human estrogen receptors is formed by the amino acids Arg 39, Leu 349, Ala 350, Thr 347, Met 388, Leu 384, Ile 424, Gly 521, and Gly 420. Methyl 4-hydroxycinnamate from MP has a binding energy of -30.3502 Kcal/mol.

Figure 4: 3D and 2D interaction of the Methyl_4-hydroxycinnamate in the active site of the human estrogen receptor

The human estrogen receptor exhibits a similar binding affinity to methyl 2,5-dihydroxycinnamate. One H-bond and other non-bonding interactions improve the binding contact in this molecule docking analysis compared to the typical medication. With the corresponding amino acid, the carboxylic acid creates three alkyl contacts and one H-bond (Figure 5). The phenyl group of the methyl 2,5-dihydroxycinnamate interacts with the Phe 404 amino acid to produce a Pi-Pi T-shaped connection.

Figure 5: 3D and 2D interaction of the Methyl_2_5-dihydroxycinnamate in the active site of the human estrogen receptor

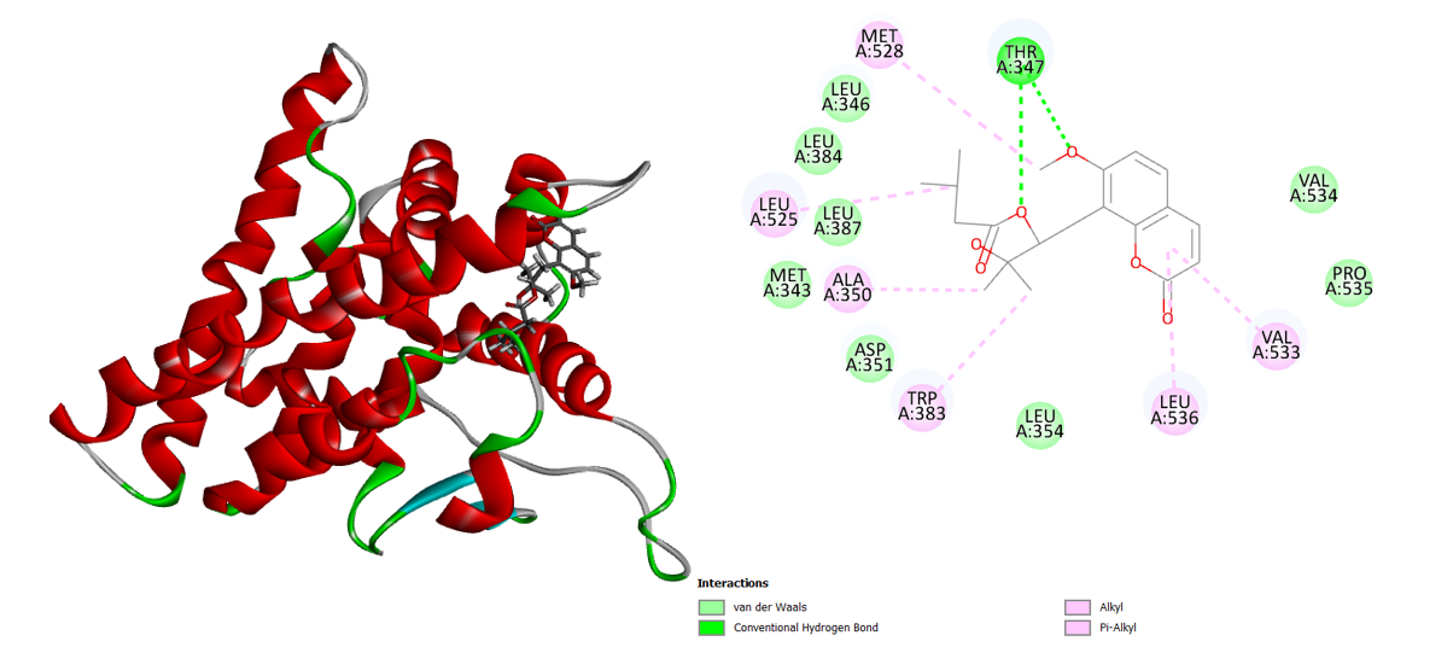

Two robust H-bonds between the murrayatin phytochemical and the amino acid Thr 347 are visible (Figure 6). Most other alkyl and aromatic compounds interact with the amino acids Val 533, Leu 536, Trp 383, Ala 350, Leu 525, and Met 528 to create alkyl and pi-alkyl associations. The murrayatin’s binding energy is -28.8854 Kcal/mol.

Figure 6: 3D and 2D interaction of the murrayatin in the active site of the human estrogen receptor

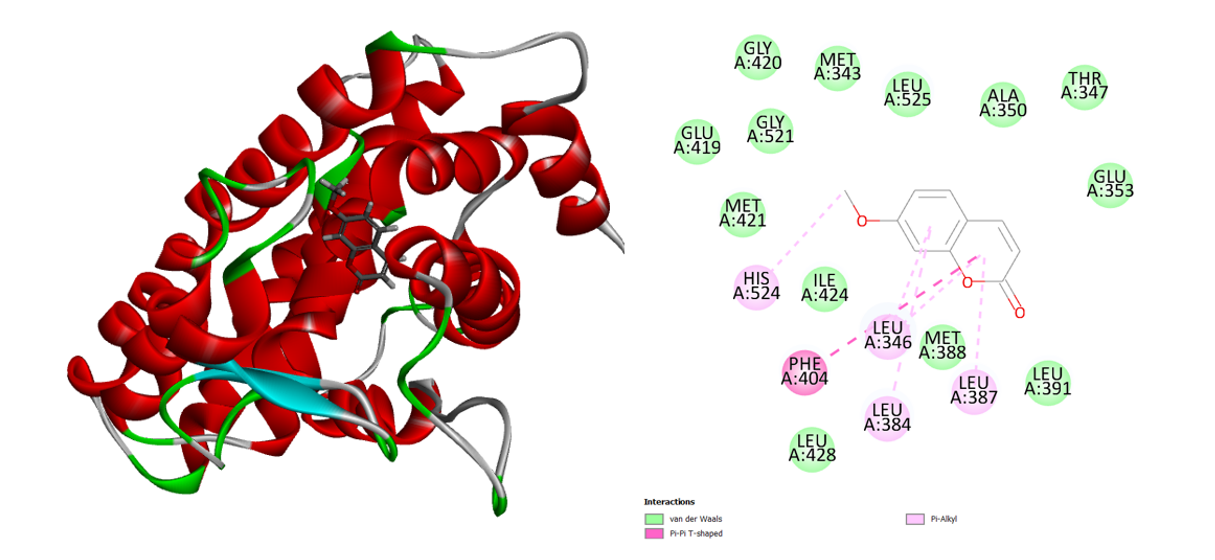

The phytochemical omphamurrayone interacts with active-site amino acids exclusively non-bondedly (Figure 7). This molecule forms an alkyl association with the amino acids Leu 346, Leu 387, and Leu 384 and has two aromatic rings. The phenyl ring of the Omphamurrayone interacts in a Pi-Pi-T configuration with the Phe 404 amino acid. Omphamurrayone’s binding energy is -26.5787 Kcal/mol.

Figure 7: 3D and 2D interaction of the Omphamurrayone in the active site of the human estrogen receptor

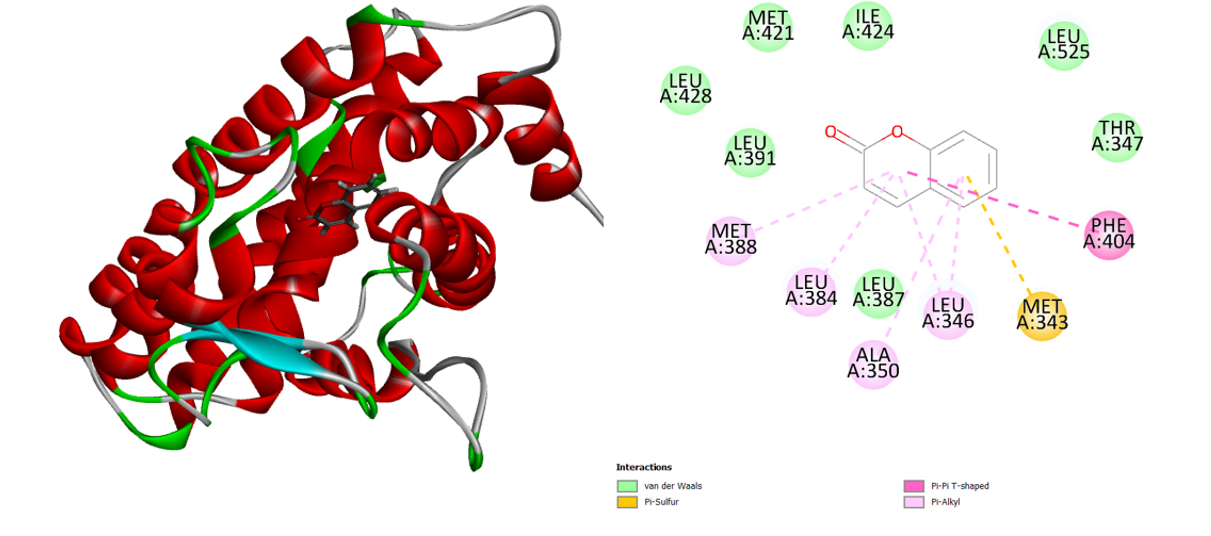

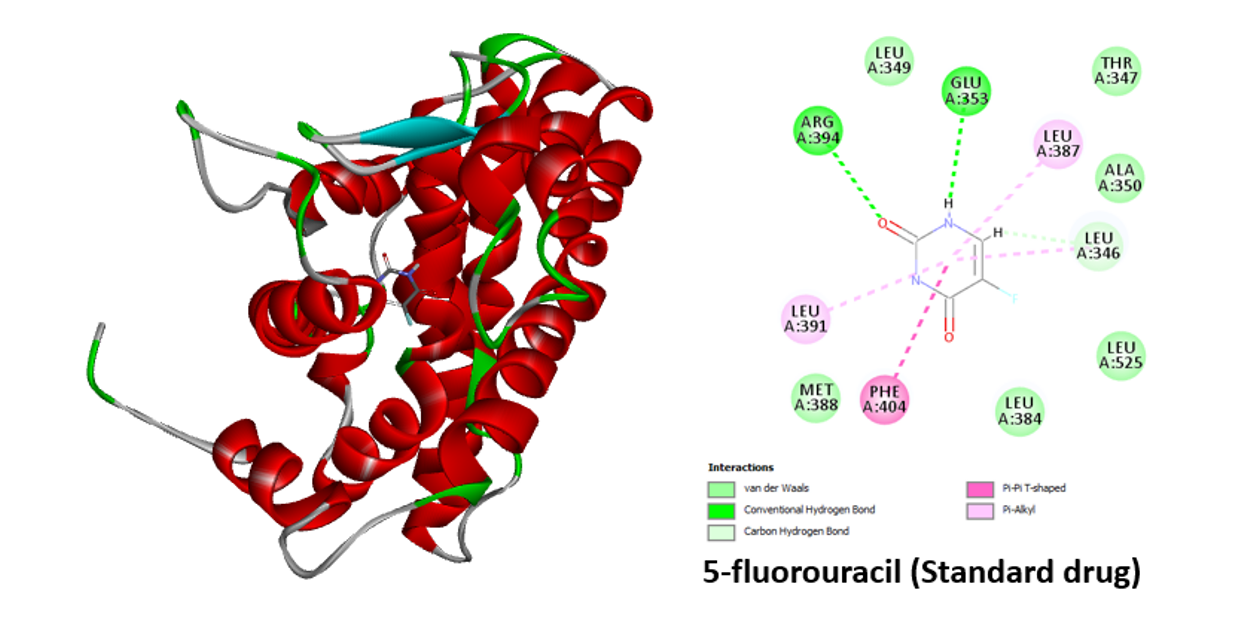

Similar binding interactions between coumarin and the human estrogen receptor are also seen. Van der Waals, Pi-alkyl, Pi-sulfur, and Pi-Pi-T-Shaped interactions were all included in this interaction analysis (Figure 8). Two hydrogen bonds are formed between the amino acids Arg 394 and Glu 353 and the common medication 5-fluorouracil (Figure 9). Compared to most of the ligands, the typical medication exhibits lower binding energy.

Figure 8: 3D and 2D interaction of the Coumarin in the active site of the human estrogen receptor

Figure 9: 3D and 2D interaction of the 5-fluorouracil in the active site of human estrogen receptor

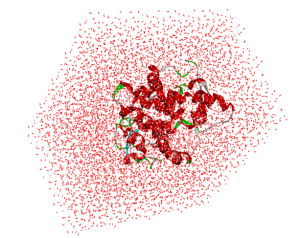

Molecular dynamics of 5,7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl) coumarin (MP): Based on docking data, we selected the best 5,7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl) coumarin with 3ERT protein for molecular dynamics simulation investigation. The simulation was done on binding complex systems to examine the dynamic behaviour of the intended protein. To get the protein ready for additional stability testing, Na, Cl, and water molecules were added to it during the solvation process (Figure 10). Temperature, pressure, and potential/kinetic energy values for the simulated system were examined to validate the simulations. According to the results, the quality check parameters remained constant throughout the simulation period.

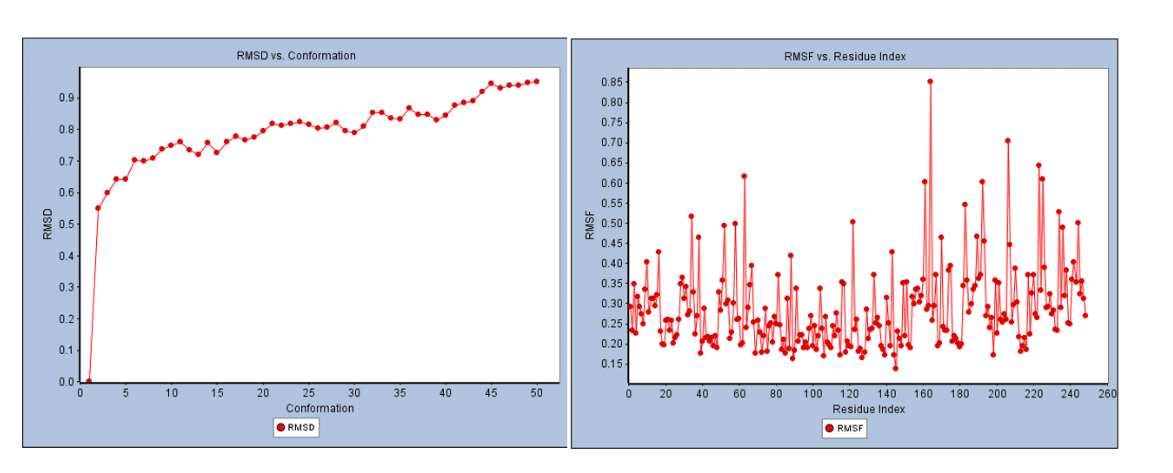

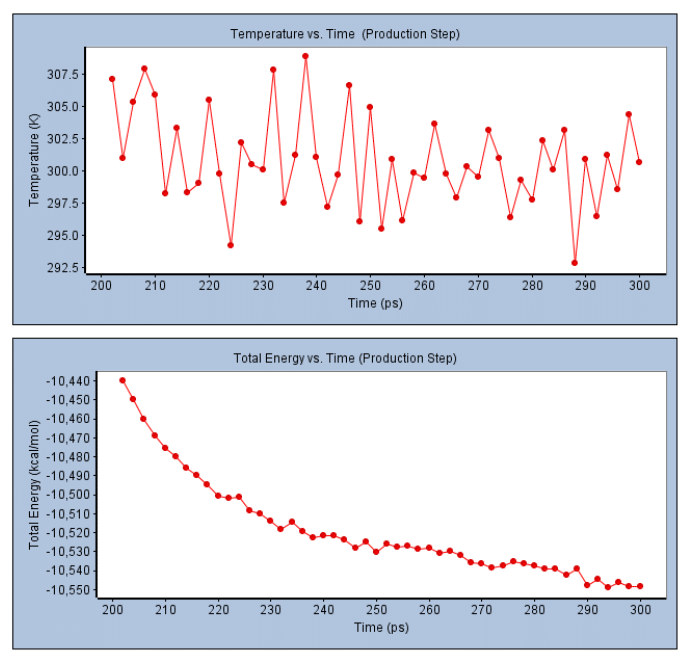

The results of the MD simulation for the 5- and 7-dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl)coumarin complex are shown in Figures 11 and 12. The systems were stable and displayed no appreciable changes in density, temperature, volume, kinetic/potential/total energies, or pressure in the unbound and lead ligand/standard inhibitor-bound protein/protein complex during the 300 ps MD simulation period. The RMSD and RMSF complexes did not differ significantly from unbound protein (Figure 11). Using RMSF, the effect of lead 5,7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl) coumarin binding on the targeted protein’s flexible region was examined. The 3ERT complex’s RMSF values were dramatically decreased. The 3ERT complex is stable, as evidenced by its temperature and stability (Figure 12). Finally, the 5,7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl) coumarin complexes did not significantly differ from unbound protein.

Figure 10: Solvation analysis of 3ERT protein with ,7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl) coumarin

Figure 11: RMSD and RSMF analysis of 3ERT protein with 5,7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl) coumarin

Figure 12: Temperature and total energy analysis of 3ERT protein with 5,7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl) coumarin

ADMET: Table 6 displays the results of the ADMET study of the main phytochemicals in MP The human estrogen receptor protein target has a better docking score for some phytochemicals than for others. Thirteen phytochemicals are present, but only 10 of them comply with the ADMET limitations and the drug-likeness LogP values (Table 6). These chemicals satisfied the requirements for lipophilicity, hydrophobicity, and polarity. The best phytochemical with drug-like qualities and polarity of phytochemical permeability in biological systems were found with the help of this study. By contrasting the marginal value with the resultant value, ADMET results are understood: Low intestinal absorption of less than 30%, high Caco-2 permeability projected value > 0.90, high BBB permeability logP > 0.3, and low logP are all indicators of poorly distributed logP. These ten phytochemicals were chosen for a protein-ligand interaction investigation to find potential hits that bind at the active sites of the corresponding human estrogen receptor protein targets.

| Molecule name | Absorption level | Solubility level | BBB level | PPB level | Hepatotoxic level | CYP 2D6 | PSA 2D | AlogP98 |

| Methyl_4-hydroxycinnamate | Good | Extremely good | Low | <90% | No | No | 61.391 | 2.761 |

| Methyl_2_5-dihydroxycinnamate | Good | Extremely good | Low | <90% | No | No | 35.16 | 1.883 |

| 5,7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl) coumarin | Good | Good | Low | <90% | No | No | 71.013 | 3.136 |

| Murrayatin | Good | Extremely good | Low | <90% | No | No | 35.16 | 5.175 |

| 7-Methoxycoumarin | Good | Extremely good | Low | <90% | No | No | 26.23 | 1.899 |

| Coumarin | Good | Extremely good | Low | <90% | No | No | 44.091 | 3.723 |

| Auraptene | Good | Extremely good | Low | <90% | No | No | 87.622 | 3.863 |

Table 6: ADMET properties of the MP phytochemicals

Limitations:

- Reliance on in silico methods: The study is limited to computational techniques, including molecular docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulations. No in vitro cell line assays or in vivo animal studies were performed to validate the anticancer efficacy or safety of the identified phytochemicals.

- Single protein target: The research focuses exclusively on the human estrogen receptor (PDB ID: 3ERT). Breast cancer is heterogeneous, and other receptor subtypes and signaling pathways (e.g., HER2, p53, BRCA1/2) were not explored, potentially limiting the broader applicability of the findings.

- Simplified ADMET prediction: The ADMET analysis was conducted using SwissADME, which, while widely used, provides theoretical predictions that may not fully represent actual pharmacokinetic behavior or toxicity profiles in humans.

- No quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling: The study lacks QSAR modeling, which could have strengthened the correlation between molecular properties and biological activity.

- Limited phytochemical spectrum: Although LC-MS identified several compounds, only a subset was analyzed through docking and dynamics simulations. Other potentially active components may have been overlooked.

Future directions

- Experimental validation: Future studies should incorporate in vitro assays using breast cancer cell lines (e.g., MCF-7, T47D, or triple-negative types) and in vivo models to validate the anticancer activity and toxicity of the lead phytochemicals.

- Mechanistic studies: Detailed investigations are needed to understand the molecular mechanisms through which these phytochemicals exert their effects on cancer signaling pathways.

- Multi-target docking: Expanding the docking studies to include multiple cancer-relevant proteins will provide a more comprehensive profile of potential anticancer efficacy.

- Lead optimization and QSAR: Future research could involve the structural modification of lead compounds followed by QSAR modeling to optimize their efficacy, selectivity, and drug-like properties.

- Synergistic effects and formulation studies: Examining the synergistic effects of these phytochemicals with existing chemotherapy agents and exploring suitable drug delivery systems (e.g., nanoparticles, liposomes) would be valuable for therapeutic development.

- Toxicological profiling and bioavailability studies: Detailed pharmacokinetic and toxicological studies are necessary to assess absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and potential side effects in animal models or preclinical settings.

Conclusion

The leaves of MP are pharmacologically active due to the presence of the discovered compounds. Their value in the prevention, management, and treatment of different diseases may be attributed to their antioxidant activity. When compared to reference compounds, all MP extracts showed acceptable antioxidant activity in vitro. The results of this study lend credence to the idea that MP, a common medicinal herb in India, may be a source of antioxidants. The use of a leaf extract as an antioxidant in natural goods for human health is a realistic alternative. To isolate and describe the pure Phyto active components for augmentation, more research is advised. Toxicity tests should be carried out to determine the safety of MP leaf extracts.

Based on in silico analysis, we found that the phytochemicals Methyl 4 hydroxycinnamate, Methyl 2 5 dihydroxycinnamate, 5,7-Dimethoxy-8-(2-oxo-3-methylbutyl) coumarin, murrayatin, 7-Methoxycoumarin, Coumarin, and Auraptene from MP have substantial binding affinity and drug-like properties. Additionally, tests on their absorption and toxicity revealed that they are both risk-free and non-toxic. These substances can therefore be utilized to fight the target proteins. Additionally, molecular dynamics simulations were employed to confirm these results, and they showed that these phytochemicals have no impact on the structural alterations in the protein complex. These results will be important in selecting a lead phytochemical for later drug development. The results, in our opinion, will facilitate the development of conventional medicine-based treatment modalities and the identification of potential hits for lead optimization in the future for the treatment of breast cancer.

References

- Nair R, Chanda S. Activity of some medicinal plants against certain pathogenic bacteria strains. Indian J Pharmacol. 2006;38(2):142-144. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.24625 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Chowdhury R, Anupam C, Costas DM. Using gene essentiality and synthetic lethality information to correct yeast and CHO cell genome-scale models. Metabolites. 2015;5(4):536-570. doi:10.3390/metabo5040536 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sharma S, Sharma S. Pharmaceutical activities of phytochemicals in Murraya spp. – A review. J Pharm Res. 2015;9:217-236. Pharmaceutical activities of phytochemicals in Murraya spp- A review

- Wu L, Li P, Wang X, Zhuang Z, Farzaneh F, Xu R. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activities of Murraya exotica. Pharm Biol. 2010;48:1344-1353. doi:10.3109/13880201003793723 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rahman MA, Hasanuzzaman M, Shahid N. Anti-diarrhoeal and anti-inflammatory activities of Murraya paniculata (L.) Jack. Pharmacologyonline. 2010;3:768-776. Anti-diarrhoeal and anti-inflammatory activities of Murraya paniculata (L.) Jack

- Kong YC, Ng KH, But PP, et al. Sources of the anti-implantation alkaloid yuehchukene in the genus Murraya. J Ethnopharmacol. 1986;15:195-200. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(86)90155-8 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Buranrat B, Mairuae N, Konsue A. Cratoxylum formosum leaf extract inhibits proliferation and migration of human breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;90:77-84. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2017.03.032 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Machana S, Weerapreeyakul N, Barusrux S, et al. Cytotoxic and apoptotic effects of six herbal plants against the human hepatocarcinoma (HepG2) cell line. Chin Med. 2011;6(1):39-46. doi:10.1186/1749-8546-6-39 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gullett NP, Amin AR, Bayraktar S, et al. Cancer prevention with natural compounds. Semin Oncol. 2010;37(3):258-281. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2010.06.014 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Pezzuto JM. Plant-derived anticancer agents. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;53(2):121-133. doi:10.1016/s0006-2952(96)00654-5 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Buranrat B, Mairuae N, Kanchanarach W. Cytotoxic and antimigratory effects of Cratoxylum formosum extract against HepG2 liver cancer cells. Biomed Rep. 2017;6(4):441-448. doi:10.3892/br.2017.871 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Liang C, Pan H, Li H, Zhao Y, Feng Y. In vitro anticancer activity and cytotoxicity screening of phytochemical extracts from selected traditional Chinese medicinal plants. J BUON. 2017;22(2):543-551. In vitro anticancer activity and cytotoxicity screening of phytochemical extracts from selected traditional Chinese medicinal plants

- Shaikh JR, Patil MK. Qualitative tests for preliminary phytochemical screening: An overview. Int J Chem Stud. 2020;8(2):603-608. doi:10.22271/chemi.2020.v8.i2i.8834 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rauf MA, Zubair S, Azhar A. Ligand docking and binding site analysis with PyMOL and AutoDock/Vina. Int J Basic Appl Sci. 2015;4(2):168. doi:10.14419/ijbas.v4i2.4123 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ng MK, Abdulhadi-Noaman Y, Cheah YK, Yeap SK, Alitheen NB. Bioactivity studies and chemical constituents of Murraya paniculata (Linn) Jack. Int Food Res J. 2012;19(4):1306-1312. Bioactivity studies and chemical constituents of Murraya paniculata (Linn) Jack

- Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1-13. doi:10.1038/srep42717. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sheikh IA, Jiffri EH, Ashraf GM, Kamal MA. Structural insights into the camel milk lactoperoxidase: Homology modeling and molecular dynamics simulation studies. J Mol Graph Model. 2019;86:43-51. doi:10.1016/j.jmgm.2018.10.008 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sun J, Zhang X, Broderick M, Fein H. Measurement of nitric oxide production in biological systems by using Griess reaction assay. Sensors. 2003;3(8):276-284. doi:10.3390/s30800276 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gautam MK, Goel RK. Exploration of preliminary phytochemical studies of leaves of Murraya paniculata (L.). Int J Pharm Life Sci. 2012;3:1871-1874. Exploration of preliminary phytochemical studies of leaves of Murraya paniculata (L.)

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

No Funding

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Sri Ramya Totakura

Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry

Care College of Pharmacy, Kakatiya University, TS, India

Email: sriramya2912@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Samatha Ampeti

Department of Pharmacology

Kakatiya University, University College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Warangal, TS, India

Swarnalatha Katherashala

Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry

Vagdevi College of Pharmacy, Kakatiya University, TS, India

Purnachandra Reddy Guntaka

Department of Pharmaceutics

GITAM Institute of Pharmacy, GITAM (Deemed to be University), Visakhapatnam, AP, India

Swapna Bongoni

Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry,

Scient Institute of Pharmacy, Ibrahimpatnam, Ranga Reddy, Hyderabad

Venkata Suresh Babu Agala

Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry

Gurunanak Institutions Technical Campus, School of Pharmacy, Ibrahimpatnam, Hyderabad

Sravanthi Chirra

Department of Pharmaceutics

Scient Institute of Pharmacy, Ibrahimpatnam, Ranga Reddy, Hyderabad

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest Statement

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Sri Ramya T, Samatha A, Swarnalatha K, et al. Virtual Screening of Potent Phytochemicals of Murraya Paniculata for Anti-Breast Cancer Activity: Molecular Docking and Dynamics Approaches. medtigo J Pharmacol. 2025;2(2):e3061223. doi:10.63096/medtigo3061223 Crossref