Author Affiliations

Abstract

Appendicitis usually presents with a classic Murphy’s triad: McBurney’s sign, vomiting, and fever. While this presentation is most common, atypical cases can occur, making it difficult to diagnose and treat. The objectives are to explore the use of ultrasound (USG) in pediatric cases and to assess the diagnostic accuracy in unusual presentations of a disease. A 12-year-old female presented with periumbilical pain, vomiting food particles, constipation, and abdominal distension for 3 days, but without fever, leukocytosis, or McBurney’s point tenderness. She was afebrile and on abdominal examination, tender over the periumbilical region, the abdomen was distended, and flanks felt full. There were no bowel sounds, and no peristaltic movement was visible. White blood count (WBC) was normal, Lymphocytes were decreased, and C-reactive protein (CRP) was increased. X-ray of the abdomen in erect posture did not reveal any perforation or inflammation. USG of the abdomen revealed appendicitis with small bowel obstruction due to fecal impaction. Plain computed tomography (CT) confirmed the diagnosis. The patient underwent an open appendectomy, which revealed a subhepatic appendicular perforation that was gangrenous and abscessed. Child had an uneventful recovery and resumed her daily routine after 14 days. To summarize, USG can diagnose Appendicitis and bowel perforation in children even when they have atypical presentation, such as no fever, no McBurney’s point tenderness, and no WBC elevation, as long as enough time is allowed. USG can also reduce the need for CT, especially in the pediatric population, where radiation exposure should be minimized. Clinicians should be aware of the variability of appendicitis presentation and the value of USG as a diagnostic tool.

Keywords

Appendicitis, McBurney’s sign, Appendectomy, Use of ultrasound, Pediatric, Radio diagnostics.

Introduction

Acute appendicitis, inflammation of the appendix, is one of the most common causes of acute abdomen in children, yet it can be difficult to differentiate from other causes of acute abdomen, demonstrating how appendicitis can still be a challenging problem for the clinician.[1,2] Appendicitis usually presents with a classic Murphy’s triad: McBurney’s sign, vomiting, and fever.[3] While this presentation is most common, atypical cases can occur, challenging the diagnosis because clinical signs, symptoms, and instrumental data can be nonspecific and unreliable, especially in younger children.[4] In terms of legal implications, Acute appendicitis ranks as the second most common cause of malpractice claims among children aged 6-17 years, the third most common for patients aged over 18 years, and the most frequent in abdominal pain-related litigation.[5] Complications such as perforated appendicitis and abscess formation increase morbidity, highlighting the importance of a prompt and accurate diagnosis.[6] This case presentation explores an unusual appendicitis presentation, highlighting the importance of considering USG for diagnosis.

Case Presentation

The case is a female patient of 12 years old, who presented with abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and vomiting for the past 3 days. The mother reported the passage of hard stools 3 days back as the last bowel movement. The vomiting was insidious in onset, non-bilious, contained food particles, was not blood-tinged, and was not projectile. Abdominal pain was periumbilical, progressing from moderate to severe, non-radiating, with no aggravating or relieving factors. She did not present with fever, rashes, melena, or loss of appetite. She denied sick contacts, recent travel, or toxin ingestion.

On initial physical examination, the abdomen appeared distended with full flanks. On palpation, the patient presented periumbilical tenderness with no local rise of temperature, no bowel sounds or peristaltic movement, and was suggestive of obstruction. She did not have any tenderness at McBurney’s point in the right lower quadrant, and the pain did not aggravate when coughing. Vital signs were as follows: heart rate: 120 beats/min; respiratory rate: 33 breaths/min; oxygen saturation at 97%; and body temperature: 37.6°C.

Upon blood investigations, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) were increased. Total WBC count was within normal limits (9,600 μL), and lymphocytes were decreased. Serum sodium and chloride were decreased, whereas high-sensitivity CRP (HS-CRP) was increased (more than 5 mg/dl; normal: 0.5-1.5). An X-ray of the erect abdomen was taken in standing posture, which showed multiple air fluid levels, fundal air in the stomach, and no air under the diaphragm. This indicated that an obstruction might be present past the level of the small intestine. The X-ray (figure 1) shows no evidence of any air under the diaphragm, and multiple air-fluid levels are noted within the visualized small bowel loops. Fundal air in the stomach is present.

Figure 1: X-ray of erect abdomen

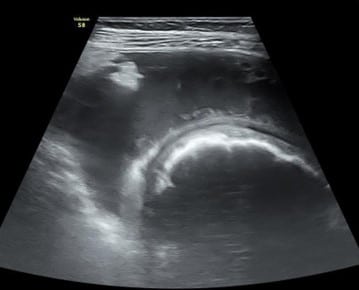

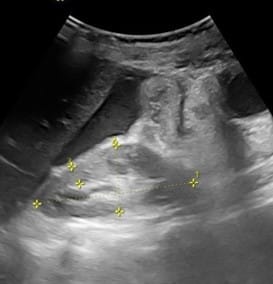

An ultrasound of the abdomen was also taken immediately after the X-ray, showing dilated bowel loops, Ascitic free fluid observed in the right iliac fossa, a Loculated collection with thick echos and echogenic lith in the appendix area, with part of the appendix visualized to be dilated, appears to be surrounded by free fluid and mesenteric inflammation. Figures 2 to 6 below show the USG images.

Figure 2: USG of abdomen showing dilated small bowel loops

Figure 3: USG of abdomen showing part of appendix- dilated, appears to be surrounded by free fluid and mesenteric inflammation

Figure 4: USG showing dilated bowel loop

Figure 5: USG showing ascitic free fluid observed in the right iliac fossa

Figure 6: USG showing loculated collection with thick echos and echogenic lith

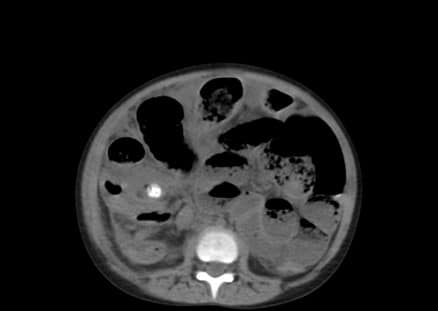

A plain CT of the abdomen was also taken to confirm the diagnosis before being taken to surgery. It showed dilated bowel loops, a radiopaque mass possibly fecalith or appendicolith, and an Inflamed and enlarged appendix. After taking the symptoms, signs, and investigations into consideration, the child was diagnosed with Appendicitis with small bowel obstruction and fecal impaction and taken to surgery. Figures 7 to 9 below show the CT images, axial section of the lower segment of the abdomen.

Figure 7: CT image of axial section of lower segment of abdomen showing dilated bowel loops

Figure 8: CT image showing radiopaque mass, possibly fecalith or appendicolith

Figure 9: CT image showing an inflamed and enlarged appendix with a possible faecolith or appendicolith

Case Management

Appendix was found to be in stage 4-perforated with abscess and gangrene formation. An open appendectomy and lavage were performed. Intraoperative findings showed an appendix that was found to be inflamed and gangrenous, with subhepatic perforation and abscess formation. (even though there was no air under the diaphragm on scanning). Pus was sent for culture and sensitivity, and the appendix specimen (figure 10) was sent to pathology. Revealed subhepatic appendicular perforation with gangrene and abscess formation.

Figure 10: Appendix specimen sent to pathology

A cover of antibiotics was given in the post-operative pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) ward. The patient recovered in the post-operative PICU, kept under observation for 2 days. Patient has passed gas and evacuated bowel, scar present at the site of surgery, which healed by primary intention. There were no new complaints or episodes of previous complaints. Child had an uneventful recovery and resumed her daily routine after 14 days.

Discussion

This case demonstrates how appendicitis can still be a challenging problem for the clinician.[2] USG can diagnose Appendicitis and bowel perforation in children even when they have atypical presentation, such as no fever, no McBurney’s point tenderness, and no WBC elevation, as long as enough time is allowed. The ability of the diagnostician to recognize appendicitis despite the atypical presentation is also an important factor in the diagnostic accuracy of USG. Classic symptoms are not always reliable or present. Training doctors to recognize unique presentations of a disease, beyond classic textbook presentations, should be encouraged.

Any misdiagnosis leads to various complications, such as delayed treatment or unnecessary surgeries, which in turn cause peritonitis and increased negative appendectomy rates.[5] CT is not always required, especially in the pediatric population. CT scan is associated with high levels of radiation. Some studies report that 20% to 40% of CT scans performed in children for the investigation of abdominal pain revealed no intra-abdominal pathology owing to the risks of radiation exposure.[7]

History and physical examination alone have a low sensitivity and specificity so that imaging may play a key role in the accurate and prompt diagnosis of suspected appendicitis. Ultrasonography has become the preferred imaging option in the assessment of children with abdominal pain.[1,8,9] Early detection and treatment depend on proper imaging and the skill of the technician. This can help prevent complications such as Appendiceal perforation, which continues to be a common occurrence in the young child and increases in frequency as the age of the patient decreases and the duration of symptoms lengthens. Besides, the complications did not vary significantly for children with suspected acute appendicitis who had CT versus USG, in conjunction with a surgical consult.[7] Perforation results in a significant increase in hospital length of stay and rate of abscess formation. Furthermore, this patient had suffered from stage 4 perforated appendix, which is an established sequelae in typically presented pediatric cases, leading to malpractice claims. USG is a valuable tool for the pediatric population, considering the time taken to diagnose using a USG versus CT. It is noninvasive, does not involve radiation, and can be carried out repeatedly with minimal harm to the patient.[9-11]

Conclusion

Appendicitis usually presents with a classic Murphy’s triad: McBurney’s sign, vomiting, and fever. While this presentation is most common, atypical cases can occur, making it difficult to diagnose and treat. USG can diagnose Appendicitis and bowel perforation in children even when they have atypical presentation, such as no fever, no McBurney’s point tenderness, and no WBC elevation, as long as enough time is allowed. Keeping cost effectiveness in mind and the speed of diagnosis by using the two modalities of imaging, USG is a better choice compared to CT. USG can also reduce the need for CT, especially in the pediatric population, where radiation exposure should be minimized. Clinicians should be aware of the variability of appendicitis presentation and the value of USG as a diagnostic tool.

References

- Wang Z hua, Ye J, Wang Y shui, Liu. Diagnostic accuracy of pediatric atypical appendicitis: Three case reports. Medicine. 2019;98(13):e15006. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000015006 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Beaumont O, Miller R. Guy Atypical presentation of appendicitis. BMJ Case Reports. 2016:bcr2016217293. doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-217293 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Borruel Nacenta S, Ibáñez Sanz L, Sanz Lucas R, Depetris MA, Martínez Chamorro. Update on acute appendicitis: Typical and untypical findings. Radiología (English Edition). 2023;65:S81-91. doi:10.1016/j.rxeng.2022.09.010 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Marzuillo P. Appendicitis in children less than five years old: A challenge for the general practitioner. WJCP. 2015;4(2):19. doi:10.5409/wjcp.v4.i2.19 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mostafa R, El-Atawi K. Misdiagnosis of Acute Appendicitis Cases in the Emergency Room. Cureus. 2024;16(3):e57141. doi:10.7759/cureus.57141 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bansal S, Banever GT, Karrer FM, Partrick DA. Appendicitis in children less than 5 years old: influence of age on presentation and outcome. Am J Surg. 2012;204(6):1031-1035. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.10.003 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Miano D, Silvis R, Popp J, Culbertson M, Campbell B, Smith. Abdominal CT Does Not Improve Outcome for Children with Suspected Acute Appendicitis. WestJEM. 2015;16(7):974-982. doi:10.5811/westjem.2015.10.25576 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Coursey CA, Nelson RC, Patel MB, et al. Making the Diagnosis of Acute Appendicitis: Do More Preoperative CT Scans Mean Fewer Negative Appendectomies? A 10-year Study. Radiology. 2010;254(2):460-468. doi:10.1148/radiol.09082298 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Marzuillo P, Germani C, Krauss BS, Barbi E. Appendicitis in children less than five years old: A challenge for the general practitioner. World J Clin Pediatr. 2015;4(2):19-24. doi:10.5409/wjcp.v4.i2.19 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Benabbas R, Hanna M, Shah J, Sinert R. Diagnostic Accuracy of History, Physical Examination, Laboratory Tests, and Point-of-care Ultrasound for Pediatric Acute Appendicitis in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(5):523-551. doi:10.1111/acem.13181 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Shah SR, Sinclair KA, Theut SB, Johnson KM, Holcomb GW, St Peter SD. Computed Tomography Utilization for the Diagnosis of Acute Appendicitis in Children Decreases With a Diagnostic Algorithm. Ann Surg. 2016;264(3):474-481. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001867 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

Not applicable

Author Information

Anusree Chalamalasetty

Department of Medicine

Sri Siddhartha Medical College, Tamilnadu, India

Email: alex.sergei.666@gmail.com

Author Contribution

The author contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles, and was involved in the writing – original draft preparation and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient and their attenders.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Anusree C. USG to the Rescue: Solving a Case of Atypical Appendicitis. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622445. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622445 Crossref