Author Affiliations

Abstract

We report the case of a 46-year-old male who presented to the emergency department (ED) in critical condition. He was found unresponsive, tachypneic, and with signs of severe respiratory distress, with both airway patency and breathing severely compromised. Due to his unstable clinical status, immediate intubation was performed to secure the airway and provide adequate ventilation. An initial electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed ventricular tachycardia with the classic morphology of Torsades de Pointes (TdP), characterized by a twisting QRS axis around the baseline. This polymorphic ventricular tachycardia is often life-threatening and requires urgent intervention to prevent progression to ventricular fibrillation. Alongside the ECG findings, arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis showed severe respiratory alkalosis, with a markedly elevated pH of 7.64, suggesting significant hyperventilation. Notably, there was also evidence of a concurrent metabolic acidosis, with a bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) level of 7.2 mmol/L, indicating a mixed acid-base disturbance likely exacerbated by underlying physiological stressors. This case also serves as a reminder that in patients with seizure disorders and multiple metabolic imbalances, clinicians should remain vigilant for arrhythmias like TdP to prevent life-threatening outcomes.

Keywords

Torsades de Pointes, Electrocardiogram, Emergency department, Arterial blood gas, Generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

Introduction

Torsades de Pointes is a unique and potentially life-threatening type of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia that typically arises in the context of a prolonged QT interval, which can disrupt the heart’s normal electrical repolarization and lead to instability in cardiac rhythms.[1] TdP often presents with a characteristic “twisting” of the QRS complexes around the isoelectric line on an ECG, giving it a distinct, sinusoidal appearance. If not identified and treated promptly, TdP can rapidly deteriorate into ventricular fibrillation, resulting in sudden cardiac death.[2]

A range of predisposing factors has been associated with the development of TdP. Electrolyte imbalances are among the most significant, particularly abnormalities in potassium, magnesium, and calcium levels. These electrolytes are crucial for proper cardiac cell function and maintaining the electrical gradient across cell membranes. Hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, and hypocalcemia can all contribute to prolonging the QT interval, thereby increasing the risk of TdP.[3] Additionally, myocardial infarction (MI) is a recognized trigger, as ischemic damage to heart tissue can disrupt electrical pathways and predispose to arrhythmias.[4]

Various medications also play a significant role in prolonging the QT interval and increasing TdP risk. Drugs such as antiarrhythmics (e.g., amiodarone), certain antibiotics (e.g., macrolides and fluoroquinolones), and some antipsychotics (e.g., haloperidol) are known to have QT-prolonging effects. These medications can alter the balance of ion channels or delay repolarization, heightening the susceptibility to arrhythmias.[5] Moreover, underlying cardiac conditions such as heart failure, cardiomyopathy, and congenital long QT syndrome further increase the risk of TdP, as structural and functional abnormalities of the heart can lead to electrical instability.[6]

Compounding these factors, respiratory failure and generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCS) can both contribute to and exacerbate electrolyte imbalances, hypoxia, and acid-base disturbances. During respiratory failure, reduced oxygenation and elevated carbon dioxide levels can lead to cellular hypoxia and acidosis, creating an environment conducive to arrhythmogenic events, including TdP.[7] Similarly, GTCS episodes can lead to transient hypoxia and severe metabolic changes, which can precipitate or worsen electrolyte disturbances, thereby increasing the risk of TdP.[8]

Identifying and managing these contributing factors is critical for preventing TdP, especially in high-risk patients. This often involves correcting electrolyte imbalances, avoiding QT-prolonging drugs when possible, and addressing any underlying medical conditions that may predispose a patient to TdP.[9] In emergency settings, interventions like intravenous magnesium sulfate are frequently used to stabilize the cardiac membrane and prevent progression to fatal arrhythmias.

Case Presentation

History and general examination: A 46-year-old male arrived at the ED unresponsive and tachypneic, exhibiting signs of a compromised airway and breathing. He had a history of weakness for 4 days and fever for the last 2 days. The emergency medical services (EMS) reported a history of generalized tonic-clonic seizures 15 minutes ago, which was controlled by a single dose of IV midazolam, suggesting he may have been in a postictal phase upon arrival. Initial vital signs revealed a temperature of 105°F, blood pressure (BP) 112/90 mmHg, a heart rate of 200 beats per minute, and tachypnea. The Patient also did not have a pulse. Random blood sugar (RBS) showed a glucose level of 290 mg/dl, which was severely hyperglycemic.

Laboratory investigations: The patient’s ABG analysis and ECG were done immediately and revealed the following findings:

ABG – Severe mixed respiratory and metabolic disturbances:

- pH: 7.64

- pCO₂: 6.6 mmHg (compensated respiratory alkalosis)

- HCO₃⁻: 7.2 mmol/L (severe metabolic acidosis)

- Base excess (BE): -13.6

Additional laboratory findings indicated:

- Sodium (Na⁺): 115 mmol/L (hyponatremia)

- Potassium (K⁺): 3 mmol/L (borderline hypokalemia)

- Calcium (Ca²⁺): 0.97 mmol/L (hypocalcemia)

- Glucose: 298 mg/dL (hyperglycemia)

- Lactate: 10.19 mmol/L (elevated, suggesting lactic acidosis)

| Parameter | Result | Units | Reference range | Interpretation |

| Gases | ||||

| pH | 7.646 | High | 7.350 – 7.450 | Alkalotic |

| pCO2 | 6.6 mmHg | Low | 35.0 – 48.0 | Hypocapnia |

| pO2 | 82.4 mmHg | Low | 83.0 – 108.0 | Hypoxemia |

| cHCO3 | 7.2 mmol/L | Low | 21.0 – 28.0 | Low bicarbonate |

| BE extracellular (BEecf) | -13.6 mmol/L | Low | -3.0 – 3.0 | Base deficit |

| cSO2 | 98.5 % | High | 94.0 – 98.0 | High saturation |

| Chemistry | ||||

| Na+ | 115 mmol/L | Low | 137.0 – 145.0 | Hyponatremia |

| K+ | 3.0 mmol/L | Low | 3.5 – 4.5 | Hypokalemia |

| Ca++ | 0.97 mmol/L | Low | 1.15 – 1.32 | Hypocalcemia |

| Cl- | 84 mmol/L | Low | 98.0 – 107.0 | Hypochloremia |

| tCO2 | 5.7 mmol/L | Low | 22.0 – 27.0 | Low Total CO2 |

| AGap | 29 mmol/L | High | 10.0 – 16.0 | High anion gap |

| Hematocrit (HCT) | 46 % | – | Normal | |

| Chromogranin B (CHGB) | 15.5 g/dL | – | Normal | |

| BE blood (BE(b)) | -8.0 mmol/L | Low | -3.0 – 3.0 | Base deficit |

| Metabolic | ||||

| Glucose | 298 mg/dL | High | 70.0 – 105.0 | Hyperglycemia |

| Lactic acid test | 10.19 mmol/L | High | 0.5 – 1.6 | High lactate |

| Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) | <3 mg/dL | Low | 8.0 – 23.0 | Low BUN |

| Urea | <1 mg/dL | Low | – | Low urea |

| Creatinine | 1.00 mg/dL | 0.6 – 1.2 | Normal |

Table 1: Laboratory investigations

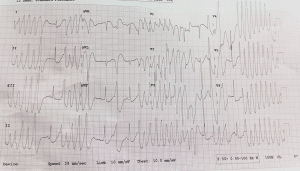

ECG findings:The initial ECG showed ventricular tachycardia with TdP morphology, likely secondary to prolonged QT due to electrolyte imbalances and recent seizure activity. The patient was pulseless on presentation with a heart rate of 200

(Figure 1).

Figure 1: ECG showing a wide QRS complex with TdP morphology

Diagnosis: TdP secondary to Respiratory Failure and GTCS accompanied by severe respiratory alkalosis and metabolic acidosis.

Case Management

Given his compromised airway and respiratory status, he was intubated with an 8.0 endotracheal tube for airway protection and ventilation support. Since the patient was pulseless on arrival, advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) protocols were immediately initiated. Magnesium sulfate and amiodarone were administered to stabilize the cardiac rhythm. Sodium bicarbonate (50 cc) was administered to correct the metabolic acidosis observed on the ABG.

To manage the patient’s hyperthermia, acetaminophen (paracetamol) was given. Midazolam and fentanyl were used for sedation during intubation, and levetiracetam (Levipil – 1 gm) was administered to manage potential seizure recurrence.

Outcome and disposition: After converting to sinus rhythm, the patient was stabilized. Despite the critical nature of his presentation, unfortunately, no ICU beds were available, so he was stabilized and transferred out to another hospital. Arrangements were made to continue close observation and supportive care.

Discussion

In respiratory failure, respiratory alkalosis and metabolic acidosis create a high-risk environment for TdP by

- Hypoxemia: Low oxygen damages cardiac cells and affects potassium channels, disrupting electrical stability.

- Respiratory Alkalosis: This causes low ionized calcium and hypokalemia, which prolongs the QT interval.

- Metabolic Acidosis: Worsens electrolyte shifts, especially affecting potassium and calcium, further impairing repolarization.

- Medication Interactions: Acid-base imbalance can heighten levels of QT-prolonging drugs.

These combined effects lead to prolonged QT intervals and increase TdP risk.[1,2,5]

This case underscores the complex interplay between metabolic disturbances, seizure activity, and cardiac arrhythmogenesis in TdP. Our patient presented with multiple risk factors that likely combined to trigger TdP. First, his metabolic abnormalities were profound, as reflected in a severe metabolic acidosis with a compensatory respiratory alkalosis. Elevated lactate levels suggested a high degree of tissue hypoxia, likely exacerbated by seizure activity, while the elevated glucose levels could indicate a stress response or possible underlying metabolic derangement.

Electrolyte abnormalities, specifically hyponatremia, hypocalcemia, and borderline hypokalemia, further contributed to the risk of TdP. Both potassium and calcium are essential in stabilizing myocardial cell membranes and maintaining normal cardiac conduction. Even modest deficiencies in these electrolytes, especially when combined, can prolong the QT interval, which predisposes the heart to arrhythmias such as TdP. The hypocalcemia may have lowered the threshold for TdP in this case, while hyponatremia likely contributed to his seizure and subsequent postictal state, worsening the metabolic and respiratory compromise.

The patient’s high fever, recorded at 105°F, also likely contributed to triggering the arrhythmia. Hyperthermia can increase the metabolic rate, exacerbating hypoxia and metabolic acidosis, which can destabilize the myocardium. Fever may also increase sympathetic activity, thereby heightening the risk of arrhythmias in patients with QT prolongation. Moreover, the elevated temperature and tachycardia raised his metabolic demand even further, perpetuating a cycle of worsening tissue hypoxia and acidosis.

Finally, the patient’s history of generalized tonic-clonic seizures introduces another layer of complexity. Seizure activity often leads to substantial catecholamine release, potentially predisposing the myocardium to arrhythmias. Additionally, the hypoxemia and metabolic imbalances seen post-seizure may have worsened cardiac electrical instability. Given the pre-existing QT prolongation due to electrolyte imbalances, the combination of recent seizure activity and metabolic disturbances likely created an environment highly conducive to TdP.

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of rapid, targeted intervention for patients presenting with TdP and complex metabolic and electrolyte disturbances. In cases like this, TdP is often precipitated by a combination of factors rather than a single cause, and each contributor—electrolyte imbalance, seizure-related catecholamine surge, acid-base disturbance, and hyperthermia—should be addressed promptly to stabilize the patient. Recognition and correction of these predisposing factors were critical in achieving a favorable short-term outcome, as TdP is potentially fatal without early intervention.

Additionally, this case emphasizes the need for a multidisciplinary approach in the emergency setting, especially when ICU resources are limited. In such situations, immediate and comprehensive management of metabolic, respiratory, and cardiac factors becomes essential to stabilize the patient and prevent recurrent arrhythmias. This case highlights the importance of sustaining vigilance for arrhythmias such as TdP in patients with seizure disorders and multiple metabolic imbalances to prevent potentially life-threatening outcomes.

References

- Tsuji Y, Yamazaki M, Shimojo M, Yanagisawa S, Inden Y, Murohara T. Mechanisms of torsades de pointes: an update. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1363848. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2024.1363848 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Viskin S, Marai I, Rosso R. Long QT Syndrome and Torsade de Pointes Ultimately Treated With Quinidine: Introducing the Concept of Pseudo-Torsade de Pointes. Circulation. 2021;144(1):85-89. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.054991 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Chen Y, Guo X, Sun G, Li Z, Zheng L, Sun Y. Effect of serum electrolytes within normal ranges on QTc prolongation: a cross-sectional study in a Chinese rural general population. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2018;18(1):175. doi:10.1186/s12872-018-0906-1 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Xu X, Wang Z, Yang J, Fan X, Yang Y. Burden of cardiac arrhythmias in patients with acute myocardial infarction and their impact on hospitalization outcomes: insights from China acute myocardial infarction (CAMI) registry. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2024;24(1):218. doi:10.1186/s12872-024-03889-w PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Roden DM. A current understanding of drug-induced QT prolongation and its implications for anticancer therapy. Cardiovasc Res. 2019;115(5):895-903. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvz013 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Tleyjeh IM, Kashour Z, AlDosary O, et al. Cardiac Toxicity of Chloroquine or Hydroxychloroquine in Patients With COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-regression Analysis. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(1):137-150. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2020.10.005 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Perkins GD, Ji C, Connolly BA, et al. Effect of Noninvasive Respiratory Strategies on Intubation or Mortality Among Patients With Acute Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure and COVID-19: The RECOVERY-RS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2022;327(6):546-558. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.0028 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Nardone R, Brigo F, Trinka E. Acute Symptomatic Seizures Caused by Electrolyte Disturbances. J Clin Neurol. 2016;12(1):21-33. doi:10.3988/jcn.2016.12.1.21 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Shenasa M, Shenasa H. Hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, and sudden cardiac death. Int J Cardiol. 2017;237:60-63. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.03.002 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

Not reported

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Rajkumar Usdadia

Department of Emergency Medicine

Saifee Hospital, Mumbai, India

Email: raj.usdadiya79@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Arman Kunju

Department of Emergency Medicine

Saifee Hospital, Mumbai, India

Ridhava Singh

Department of Medicine

Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences, Loni, India

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s daughter for publication of this case report.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Rajkumar U, Ridhava S, Arman K. Torsades de Pointes Secondary to Respiratory Failure and GTCS. medtigo J Emerg Med. 2024;1(1):e3092115. doi:10.63096/medtigo3092115 Crossref