Author Affiliations

Abstract

Background: Early Warning Scores (EWS) have been widely studied and applied in high-income countries (HIC) for more than a decade, especially in Europe. However, the EWS in low-income countries (LIC’s) such as Tanzania has not been assessed. Given the high acuity and wide range of challenges in the management of critically ill patients in the emergency departments (ED) in LIC’s, it is possible that having an EWS would improve patient management and outcomes.

Methods: A prospective study of adult non-trauma, non-pregnant patients from October 2018 to January 2019 at Muhimbili National Hospital (MNH) and Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences’ (MUHAS) Academic Medical Center (MAMC), where blood pressure (BP), pulse rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, temperature, Alert, Verbal, Pain, and Unresponsive (AVPU) were used to calculate an EWS obtained at 15 minutes (EWS1) and after 2 hours (EWS2). The primary outcomes were need for mechanical ventilation, cardiac arrest and death (regarded as serious adverse events (SAEs)) in the EDescriptive non parametric data were reported with median and interquartile range while a proportion was used to describe incidence of categorical descriptive variables. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) was drawn to calculate the optimum cut-off of the EWS, as well as its sensitivity and specificity. The odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals was used to determine predictors of serious adverse events, P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results: We enrolled 527 patients with a median age of 52.0 (interquartile range (IQR) 38.5-66.0) years, and 52.0% were males. A total of 522 (99%) out of the 527 received an initial EWS assessment (EWS1), and 507 (96.2%) received a second EWS (EWS2). The median EWS1 was 5.0 (IQR 2-5) and ranged from 0 to 14, whereas the median for EWS2 was 3.0 (IQR1-5) and ranged from 0 to 15. A total of 62 (11.9%) patients developed serious adverse events during the initial assessment (EWS1) with the median EWS in this group was 6.4 (IQR4-9) while patients who did not develop SAEs 460 (88.1%) had a median EWS1 of 4.0 (IQR 2-4). A total of 54 out of 507 who were recorded in the second assessment developed SAE’s with the median EWS2 of 5.4 (4-8), whereas the remaining 453 patients who did not develop serious adverse events had the median early warning score (EWS2) of 3.0 (IQR1-5), p <0.001. The AUROC-1 curve for EWS1 for overall SAEs was 0.76 (p-value 0.0001, 95% CI 0.69-0.83), with the optimum cut-off point (EWS) score of 5.5, which had a sensitivity of 72.5% and specificity of 70 %. AUROC -2 curve for EWS2 for overall SAEs was 0.75 (p-value 0.0001, 95% CI 0.68-0.82) with the optimum cut-off (EWS2) score of 4.5 and sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 72 %.

Keywords

Early warning score, Emergency department, Serious adverse events, Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, Low-income countries.

Introduction

EWS was introduced based on the fact that acute or critical illness, which can result in serious clinical adverse outcomes such as cardiac arrest and death, are normally preceded by derangement of physiological parameters called “Early Warning Signs”; these are actually not something different but Vital signs.[3] Therefore, close monitoring of the early warning signs can assist doctors or nurses in easily recognizing or predicting patient clinical deterioration and so escalating the response for interventions.[4,5]

In many HICs, the EWS has been externally and internally validated and applied in pre-hospital, in-hospital, and emergency settings. It has been shown to have a significant positive impact on the care of patients, helping to identify patients before undergoing serious adverse events or catastrophic deterioration.[6,7] However, the utility and implementation of the EWS in the population of LIC, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, is still very low, and there are very few studies done in this part of the world.[8,9] In LICs, triage is a relatively new concept and is generally simplified to 3 levels; the levels give a general idea of the patient’s clinical stability and direct where and when to be attended in the ED. However, once in that area, there is no further designation of acuity to direct which patients should be cared for first. Emergency Medicine (EM) and critical care in LICs have many challenges, including crowding of EDs with very critical patients, the EWS has not been used, but could be useful to distinguish patients who need close monitoring. However, many patients have different diseases, and usually come in later in their illnesses, and it is not certain if the EWS could be adapted to our settings.[10,11] This means that after the initial stabilization, as more patients come into the room, a system that would make sure that patients remain stable and are not further deteriorating while paying attention to new patients.

Studies have shown that longitudinal measurements and continuous monitoring of routine early warning signs in ED particularly in LIC’s are inadequate due to shortage of equipment, trained clinical staff and inefficiency in capturing reliable patient data for intervention in clinical settings for example patients must be removed from cardiac and oxygen monitors to assess the next patient. For instance, conditions such as sepsis or lactate can rarely be identified in clinical settings, and unfortunately, it is difficult to re-evaluate patients frequently and adequately using laboratory investigations (like lactate in sepsis) due to limited resources. Therefore, deteriorating patients may be at risk of going undetected during their ED stay and so make them vulnerable to develop serious adverse clinical outcomes such as unexpected respiratory failure and cardiac arrest, mechanical ventilation including intubation, increased length of hospital stay, and unnecessary admissions, which result in increased consumption of resources.[12]

Decisions to dispose of patients to Intensive care unit (ICU) or High dependent unit (HDU) are determined by factors such as availability of beds, availability of nurses, ventilators, and sometimes the btype of illness and age. With limited availability of HDU and ICU, identifying or recognizing the sickest patients allows appropriate prioritization and allocation to the correct level of care, and avoids or prevents serious adverse events or clinical outcomes, including death, as well as prevents unnecessary utilization of limited resources. The advantage of using the EWS as a longitudinal and objective patient scoring system, compared with other triage systems, is that it is simple and easy to apply. The early warning score is particularly appropriate for use in resource-limited settings and situations where health service providers have limited training and experience and where laboratory testing is limited by resources and the patient’s ability to pay. Additionally, EWS standardizes assessment and monitoring of critically ill patients, enabling a rapid and timely response using a common language in the ED.[13] Despite the validation, wide acceptance, and application of the early warning score in high-resource countries, the most important question is whether the EWS can equally apply in LIC, considering the fact that these countries have different patient demographics, disease patterns, health systems, clinical settings, and resources.[14]

In Tanzania and especially at the EMD of MNH, and MUHAS Academic Medical Center, the EWS is not applied. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the utility of the early warning scores in predicting serious adverse events or clinical outcomes in the population and clinical setting of LIC’s such as Tanzania.

Methodology

Study design: This was a prospective observational study of adult non-trauma patients triaged to the resuscitation rooms (level 1 acuity) in the EMD of MNH and MUHAS Academic Medical Center in Dar es Salaam Tanzania, over a period of three months (October 2018- January 2019).

Study setting: This study was conducted at two EDs of university teaching hospitals in Dar es Salaam, United Republic Tanzania. MNH is situated in Ilala, one of the five municipalities of Dar es Salaam City. MNH is the university teaching hospital serving as the national referral hospital with a bed capacity of 1500 beds. The ED of MNH opened in 2010 and is the largest of all EDs in the country, with a daily attendance of about 200 patients. The ED of MUHAS Academic Medical Center was inaugurated in 2017, situated in Ubungo municipal in the City of Dar-es –salaam about 20 kilometres from Muhimbili National Hospital. It is the second largest ED of a University Teaching Hospital in the country, receiving about 20,000 admissions per year, which equals around 50 patients per day.

Study participants: All adult patients aged 18 years and above were taken to resuscitation rooms in the ED of MNH and MUHAS academic medical center, excluding those who were pregnant and trauma cases.

Study protocol: Research assistants were scheduled to collect data in 12-hour shifts, and during that time, all patients who were triaged to resuscitation rooms were enrolled consecutively. Demographics, clinical presentation, records of six vital signs (BP, Pulse rate, Respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, temperature and level of conscious-AVPU) and calculation of early warning score (EWS) at 15 minutes on arrival (EWS1) and after 2 hours (EWS2), all enrolled patient were followed for 24 hours and outcomes were documented using a structured case report form then used to record all participants’ information and entered into a Redcap software program (Research Electronic Data Capture) (RedCap, version 6.0.1, Vanderbilt University Tennessee, USA). All patients were followed up in a hospital ward (if admitted) or through mobile phone calls if discharged to determine their outcome, including mortality, within 24 hours.

Outcomes: The primary outcomes were mechanical ventilation, cardiac arrest, and death in the EDs (called SAEs); secondary outcomes were disposition status and 24-hour mortality.

Data analysis: Data from the RedCap (Version 6.0.1, Vanderbilt University, Tennessee, USA) was exported into an Excel file (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), then imported and analyzed using IBM statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) statistics v23x64. Descriptive nonparametric data were reported with median and interquartile range, while a proportion was used to describe the incidence of categorical descriptive variables. The AUROC curve was drawn to calculate the optimum cut-off of the EWS, sensitivity, and specificity. The Odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals was used to determine predictors of serious adverse events, P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

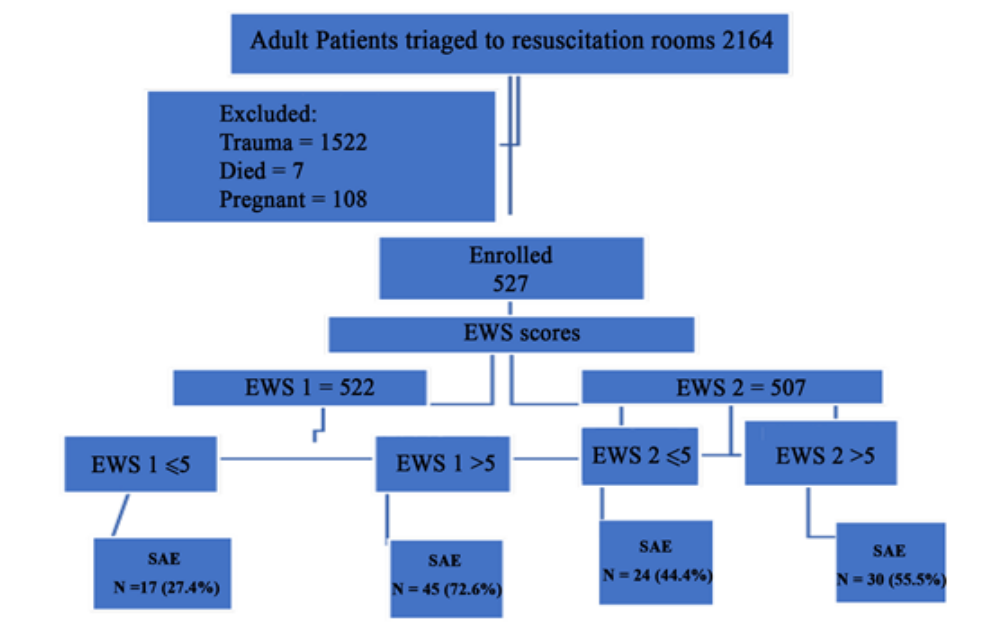

Demographics and clinical profiles: A total of 2164 adult patients who were triaged to level 1 of care at EMD (or resuscitation rooms) and excluded 1637 (75.6%) of these; 1522 were trauma patients, 108 were pregnant and 7 died immediately before any assessment. We therefore enrolled 527 patients who met the inclusion criteria. The median age was 52.0 (IQR 38.5-66.0) years, and 52.0% were males. Half of the patients, 266 (50.7%), who met the inclusion criteria were referred from other hospitals, and others were self-referrals or brought by police or good Samaritans. The majority (62.2%) had one or more comorbidities, with hypertension (HTN) being the most common. A total of 522 (99%) out of the 527 received an initial EWS assessment (EWS1), and 507 (96.2%) received a second EWS (EWS2). Complete data for both time points could not be obtained because some patients were taken out for diagnostic tests, shifted to other units, or simply not recorded at all (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1: Screening flow diagram

| Demographics | Numbers | Percentage (%) | |

| Age | 18-40 | 153 | 29.0 |

| 41-60 | 194 | 36.8 | |

| 61-80 | 152 | 28.8 | |

| >81 | 28 | 5.3 | |

| Sex | F | 253 | 48.0 |

| M | 274 | 52.0 | |

| Referral

|

Hospital | 266 | 50.7 |

| Home/unknown/police | 259 | 49.3 | |

| Comorbidity | HTN | 178 | 35.7 |

| Diabetes mellitus (DM) | 86 | 17.3 | |

| Human immune-deficiency virus (HIV) | 58 | 11.6 | |

| Chronic kidney disease(CKD) | 37 | 7.4 | |

| Cancers | 23 | 4.6 | |

| Heart failure | 18 | 3.6 | |

| None | 188 | 37.8 | |

Table 1: Demographic characteristics

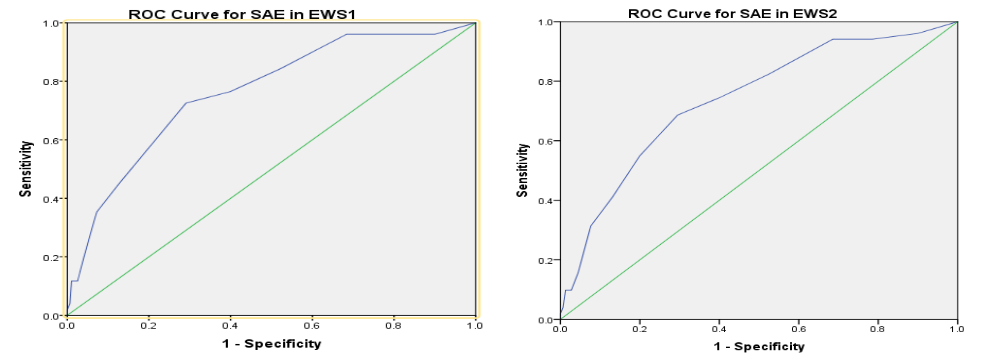

ROC curve performance for EWS: The AUROC-1 for EWS1 for overall SAEs was 0.76 (p-value 0.000, 95% CI 0.69-0.83), with the optimum cut-off point (EWS) score of 5.5, which had a sensitivity of 72.5% and specificity of 70 %. The AUROC -2 for EWS2 for overall SAEs was 0.75 (p-value 0.00, 95% CI 0.68-0.82) with the optimum cut-off (EWS2) score of 4.5 with a sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 72 % (Figures 2).

ROC curve for EWS1 and EWS2:

Figure 2: ROC curves

EWS and prediction of SAEs: Overall 62 developed SAEs during initial assessment with median (EWS1) of 6.4, of these 45 (72.6%) patients had median EWS1> 5, (odds ratio (OR) 5.9 95%, CI 3.2-11.1, p value 0.001) and 54 patients developed SAEs during consecutive assessment with median (EWS2) of 5.4, of these 30 (55.5%) patients had median EWS2> 5 (OR 6.2 (95% CI 3.4-11.5, p value 0.001) The difference in median EWS1between those with and without SAE’s was statistically significant (Using Mann-Whitney U test, p<.0001) (Table 2).

| Overall | SAEs | NO SAEs | Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon W (Test) | P-value | |

| EWS1 | 5.0 (2-7) | 6.4 (4-9) | 4 (2-6) | -4 .09 | 0.001 |

| EWS2 | 3.0 (1-5) | 5.4 (4-8) | 3 (1-5) | -6.001 | 0.001 |

Table 2: Overall early warning score and SAEs

A total of 174 patients had median EWS1 > 5; of these, 35 were mechanically ventilated, while 16 of 348 with median EWS1 ≤ 5 were mechanically ventilated (OR = 5.23, 95% CI 2.8-9.7, P value 0.001). A total of 8.0 (4.6%) patients out of 174 with EWS1 > 5 developed cardiac arrest compared to 1 (0.3%) out of 348 with EWS ≤ 5 who developed cardiac arrest (OR = 16.7, 95% CI 2.1-134.8, = 0.001) and 2.0 (1.1%) out of 174 with EWS1>5 died compared to no death out of 348 patients with EWS1 ≤5 (Odds ratio = 1.012, 95% CI 0.99 -1.03, p value 0.11). A total of 17 (18.7%) patients out of 91 with median EWS2 >5 were mechanically ventilated compared to 17 (4.1%) out of 399 patients with median EWS2 ≤ 5 (Odds ratio = 5.392, 95% CI 2.63-11.04). A total of 3.0 (3.3%) out of 91 patients with EWS2 >5, developed cardiac arrest as compared to 1.0 (0.2%) out of 416 patients with EWS2 ≤5, (OR =14.15, 95% CI 1.45-137.6, p value 0.020), and 10 (11.0%) out of 91 with EW>5 died as compared to 6 (1.4%) out of 416 with EWS2 ≤5 (OR = (8.43, 95% CI 2.98-23.8. P value 0.001) (Table 3).

| Overall N=522 |

EWS1≤5 N= 348 |

EWS1>5 N = 174 |

OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Mechanical Ventilation | 51 (9.7%) | 16 (4.6%) | 35 (20.1%) | 5.2 (2.8-9.7) | 0.001 |

| Cardiac Arrest | 9 (1.7%) | 1 (0.3%) | 8 (4.6%) | 16.7 (2.1-134.8) | 0.001 |

| Death | 2 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.1%) | 1.0(0.99.103 | 0.111 |

| Overall | EWS2≤5 N = 416 |

EWS2>5 N=91 |

|||

| Mechanical Ventilation | 34(62.9%) | 17 (4.1%) | 17 (81.3%) | 5.4(2.63-11.0) | 0.001 |

| Cardiac arrest | 4 (7.4%) | 1 (0.2%) | 3 (3.3%) | 14.2(1.45-137.6) | 0.020 |

| Death | 16(29.6%) | 6 (1.4%) | 10 (11.0%) | 8.4 (2.98-23.8) | 0.001 |

Table 3: Early warning and prediction of SAEs

Disposition and 24-hour mortality:

The majority of patients (430, 81.6%) were admitted to the general ward with a median EWS1 of 5.0 (IQR 3.0-9.0) and EWS2 of 4.0 (IQR 2-6). Fifty (9.5%) patients were admitted to HDU/ICU, their median EWS1 and EWS2 were 7.3 (IQR5.0-13.) and 5.5 (IQR3.0-8.0) respectively. Of the 20 (3.0%) discharged home, the median EWS1 and EWS2 was 3.0. A total of 18 (3.4%) died in the EMD (EMD mortality), the ICU/HDU mortality in 24 hours was 18%, and the overall 24-hour mortality was 40 (7.9%) (Table 4).

| Disposition status | Number | (%) | EWS1 (median) |

IQR | EWS2 (median) |

IQR | ||

| Discharge home | 20 | 3.0 | 3.0 | (0-4) | 3.0 | (0-4) | ||

| Wards | 430 | 81.6 | 5.0 | (3-9) | 4.0 | (2-6) | ||

| ICU/HDU | 50 | 9.5 | 7.3 | (5-13) | 5.5 | (3-8) | ||

| Died at EMD | 18 | 3.4 | 8.0 | (5-14) | 7.2 | (4-13) | ||

| ICU/HDU mortality | 9 | 18.0 |

* Excluding EMD mortality **Including EMD and Inpatient

|

|||||

| Ward mortality | 13 | 3.0 | ||||||

| Overall Inpatient mortality* | 22 | 4.5 | ||||||

| 24-hour mortality** | 40 | 7.9 | ||||||

Table 4: Disposition and 24 hours mortality

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prospective observational study to be conducted at two EDs in Tanzania and East Africa using the standard early warning score. The AUROC of the EWS for any SAE was 0.76 for the first score (EWS1) and 0.75 for the second (EWS2), indicating fair discriminatory power of EWS in our setting.

The calculated optimum cut-off for the EWS to predict the occurrence of serious adverse events was found to be 5.5 for EWS1 and 4.5 for EWS2. In prior studies in HIC, a cut-off of ≥ 5 has been used in both wards and ED as a critical value of the early warning score.[15,16]

This study revealed that patients who developed SAE’s had overall relatively high early warning scores with medians of 6.4 and 5.4 for EWS1and for EWS2respectively. In South Africa, a study done using a MEWS found that patients with a MEWS of ≥ 5 were more likely to be admitted (risk ratio 1.7; 95% CI 1.5 to 2.0), and 24% of those admitted died during the hospital stay.[17,18]

A study done in the Netherlands (a HIC), which recorded EWS at different intervals, showed that an EWS obtained immediately on arrival was associated with ICU admission, length of hospital stay, and mortality.[11]

In Denmark a study done using a nurse administered EWS found that a total of 32 patients who had an EWS ≥ 5, were associated with a significantly increased risk of death within 48 hours of arrival (RR 20.3; 95% CI 6.9-60.1), ICU admission within 48 hours of arrival (RR 4.1; 95% CI 1.5- 10.9) and of being critically ill accordingly (RR 6.8; 95% CI 3.3-13.8) compared to a EWS < 5. Furthermore, EWs were capable of categorizing patients into high-risk and low-risk.[19,20]

In Uganda (a LIC), a study was done that involved in-hospital patients, demonstrating that 11.7% of ward patients were critically ill using the MEWS with a cut-off of 5.0.[21]

The median of EWS1, which was obtained 15 minutes after entering the resuscitation room, was 5.0, and that of EWS2 was 3.0; the decrease in EWS from 5.0 to 3.0 could be explained by resuscitative interventions or efforts undertaken for the period of two hours. The study also illuminated the important role of the ED in resuscitating acutely ill patients. A similar study was done in the United Kingdom with a sample of 709 patients, which demonstrated that MEWS obtained immediately on arrival was relatively high as compared to scores obtained later, which suggested the benefit of treatment. Hence, it was recommended that MEWS could be applied as a tool for assessing the efficiency and effectiveness of medical interventions.[6]

A total of 430 (81.6%) patients were admitted to the general ward with a median EWS1 of 5.0, while 50 (9.5%) were admitted to the ICU/HDU with a median EWS1 of 7.3. This compares equally with a study in Scotland, which looked at the utility of a single early warning score in patients with sepsis in the ED. The results showed that patients admitted to the ICU had a NEWS of 9.0 and the non-ICU group had a NEWS of 6.0 (p<0.05).

Strengths of this study include a prospective observational design, using a heterogeneous group of patients with a variety of conditions, and a multicenter study. The EWS was measured at different time points after a patient was triaged to the resuscitation room; differences in the early warning score could be used to assess the efficiency of interventions. We also followed patients after admission for 24 hours to determine how well the score could be used to predict the need for a higher level of care or serious adverse events in the wards. This study demonstrated that the use of the standard EWS is possible and easier in the EMD in low-resource settings and further demonstrated its applicability and ease of use because it is based on information routinely gathered in any ED and is objective in that it uses quantitative measurements.[22,23,24,25] Therefore, in settings of limited (material and human) resources, such as Tanzania, the tool can be conveniently applied to sort out and accelerate consultation, discharge, and admission to general, high-dependent, or intensive care units. This has the potential to speed decision making, increase smooth patient flow, and reduce overcrowding in the ED.

Errors in data collection and calculations, the process of taking vital signs and scoring was associated with challenges and unpreventable errors due to machines, observer variability, difficulty in keeping time, due to overcrowding, and vital signs could be used for another patient in a different room. A study that used an admission early warning score to predict patient morbidity, mortality, and treatment success in Ireland also reported similar study limitations. Another limitation is that the EWS was not used for decision making; it is not clear what would happen if providers used EWS to prioritize care and make admission decisions. The number of patients analyzed for demographic and clinical profile (527) differs from those analyzed for early warning score EWS1 = 522, and EWS2 = 507. It was not possible to collect all data for all patients at all-time points due to inevitable logistic reasons, such as some patients were shifted to other triage units, or immediately admitted, avoiding overcrowding, or taken to the operating room; This, however, did not affect the sample size, as it was larger than expected.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that the EWS is applicable to EDs in limited resource settings. EWS can be obtained quickly, does not require any laboratory investigations, and uses all physiological parameters routinely taken in ED settings in LIMCs. Its ability to discriminate between those who will and won’t have AE is comparable to that found in higher-income settings. Use of EWS could provide a useful objective longitudinal monitoring ssystem in the resuscitation units for early prediction and recognition of patients with greatest risk of undergoing serious adverse events. Further studies should focus on validation using a heterogeneous population, using the sequential scoring of EWS, in which providers would be aware of whether EWS prevents serious events.

References

- Subbe CP, Kruger M, Rutherford P, Gemmel L. Validation of a modified Early Warning Score in medical admissions. QJM. 2001;94(10):521-526. doi.10.1093/qjmed/94.10.521. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Subbe CP, Gao H, Harrison DA. Reproducibility of physiological track-and-trigger warning systems for identifying at-risk patients on the ward. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(4):619-624. doi.10.1007/s00134-006-0516-8. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Franklin C, Mathew J. Developing strategies to prevent in-hospital cardiac arrest: analyzing responses of physicians and nurses in the hours before the event. Crit Care Med. 1994;22(2):244-247. Developing strategies to prevent in-hospital cardiac arrest: analysing responses of physicians and nurses in the hours before the event

- Buist MD, Jarmolowski E, Burton PR, Bernard SA, Waxman BP, Anderson J. Recognising clinical instability in hospital patients before cardiac arrest or unplanned admission to intensive care: a pilot study in a tertiary-care hospital. Med J Aust. 1999;171(1):22-25. doi.10.5694/j.1326-5377.1999.tb123492.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD). Cardiac Arrest Procedures: Time to Intervene? Report. 2012. National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD)

- Groarke JD, Gallagher J, Stack J, et al. Use of an admission early warning score to predict patient morbidity and mortality and treatment success. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(12):803-806. doi.10.1136/emj.2007.051425. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bleyer AJ, Vidya S, Russell GB, et al. Longitudinal analysis of one million vital signs in patients in an academic medical center. Resuscitation. 2011;82(11):1387-1392. doi.10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.06.033

PubMed | Crossref Google Scholar - Government of Ireland. Housing for All – A New Housing Plan for Ireland. 2021. Housing for All: A New Housing Plan for Ireland

- Opio MO, Nansubuga G, Kellett J. Validation of the VitalPAC™ Early Warning Score (ViEWS) in acutely ill medical patients attending a resource-poor hospital in sub-Saharan Africa. Resuscitation. 2013;84(6):743-746. doi.10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.02.007 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Royal College of Physicians. National Early Warning Score (NEWS): Standardizing the Assessment of Acute-Illness Severity in the NHS. London: RCP; 2012. Royal College of Physicians. National Early Warning Score (NEWS): Standardizing the Assessment of Acute-Illness Severity in the NHS.

- Alam N, Vegting IL, Houben E, et al. Exploring the performance of the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) in a European emergency department. Resuscitation. 2015;90:111-115. doi.10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.02.011 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Abbott TEF, Vaid N, Ip D, et al. A single-center observational cohort study of admission National Early Warning Score (NEWS). Resuscitation. 2015;92:89-93. doi.10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.04.020 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rylance J, Baker T, Mushi E, Mashaga D. Use of an early warning score and ability to walk predicts mortality in medical patients admitted to hospitals in Tanzania. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103(8):790-794. doi.10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.05.004. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cattermole GN, Mak SP, Liow CE, et al. Derivation of a prognostic score for identifying critically ill patients in an emergency department resuscitation room. Resuscitation. 2009;80(9):1000-1005. doi.10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.06.012 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hancock A, Hulse C. Recognizing and responding to acute illness: using early warning scores. Br J Midwifery. 2014. Recognizing and responding to acute illness using early warning scores

- Duncan KD, McMullan C, Mills BM. Early warning systems: The next level of rapid response. Nurs. 2012;42(2):38-44. doi.10.1097/01.NURSE.0000410304.26165.33 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Burch VC, Tarr G, Morroni C. Modified early warning score predicts the need for hospital admission and in-hospital mortality. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(10):674-678. doi.10.1136/emj.2007.057661 PubMed | Crossref |

Google Scholar - Fullerton JN, Price CL, Silvey NE, Brace SJ, Perkins GD. Is the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) superior to clinician judgment in detecting critical illness in the pre-hospital environment? Resuscitation. 2012;83(5):557-562. doi.10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.01.004 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Christensen D, Jensen NM, Maaløe R, Rudolph SS, Belhage B, Perrild H. Nurse-administered early warning score system can be used for emergency department triage. Dan Med Bull. 2011;58(6). Nurse-administered early warning score system can be used for emergency department triage

- Armagan E, Yilmaz Y, Olmez OF, Simsek G, Gul CB. Predictive value of the modified Early Warning Score in a Turkish emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2008;15(6):338-340. doi.10.1097/MEJ.0b013e3283034222 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kruisselbrink R, Kwizera A, Crowther M, et al. Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) identifies critical illness among ward patients in a resource-restricted setting in Kampala, Uganda: a prospective observational study. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151408 doi.10.1371/journal.pone.0151408 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Haniffa R, Isaam I, De Silva AP, et al. Performance of critical care prognostic scoring systems in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):18. doi.10.1186/s13054-017-1930-8 PubMed | Crossref |

Google Scholar - So SN, Ong CW, Wong LY, Chung JYM, Graham CA. Is the Modified Early Warning Score able to enhance clinical observation to detect deteriorating patients earlier in an Accident & Emergency Department? Australas Emerg Nurs J. 2015;18(1):24-32. doi.10.1016/j.aenj.2014.12.001 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Corfield AR, Lees F, Zealley I, et al; Scottish Trauma Audit Group Sepsis Steering Group. Utility of a single early warning score in patients with sepsis in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2014;31(6):482-487. doi.10.1136/emermed-2012-202186 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bilben B, Grandal L, Søvik S. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) as an emergency department predictor of disease severity and 90-day survival in the acutely dyspneic patient: a prospective observational study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24:80. doi.10.1186/s13049-016-0273-9 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank all participants, including Dr. Mpembeni and research assistants, for making the project successful.

Funding

This project was self-funded; the principal investigators used their own funds to facilitate all activities related to the research.

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Kitapondya Deus Ngelela

Department of Emergency Medicine

Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Email: kitapondya@yahoo.com

Co-Authors:

Uwezo Edward, Hendry R. Sawe, Michael Kiremeji, Juma A. Mfinanga

Department of Emergency Medicine

Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Mike Runyon

Department of Emergency Medicine

University of North Carolina, Atrium Health system, USA

Ellen J. Weber

Department of Emergency Medicine

University of California, San Francisco, USA

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Informed Consent

Not applicable

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the MUHAS Senate of Research and publication committee (institutional review board). The executive director of MNH and MAMC, as well as the heads of the department of emergency medicine, provided permission and facilitation for the data collection process. All eligible patients who were taken to resuscitation rooms were enrolled after obtaining informed consent from them, relatives, or any caretaker. Data was coded to hide the patient’s identity and stored on a computer with a password known only to researchers. Patient management/treatment was not affected in any way by study procedures.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Kitapondya ND, Uwezo E, Michael K, et al. The Utility of Early Warning Score (EWS) in Predicting Serious Adverse Events Among Patients Presenting to Emergency Departments of Muhimbili National Hospital and MUHAS Academic Medical Center. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622421. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622421 Crossref