Author Affiliations

Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis are increasing over the period. The cause of neurological disorders is linked to the immune system’s malfunction. This review aims to explore the correlation between immunity and neurological disorders. Immune cells such as microglia, astrocytes, and tissue-resident memory T cells play an important role in normal brain functioning as well as neuroinflammatory responses. Recent research also highlighted that gut microbiota impacts immune responses, playing a vital role in neurological diseases. This review also included the mechanism of interaction between immune cells and neurons. It also identifies that acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter, has potential therapeutic implications. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR-Cas9) gene editing is an emerging therapy for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. It aims to correct genetic mutations and modulate immune responses. Future research should focus on rigorous clinical trials to enhance efficacy and decrease the adverse effects of the promised medicines. To develop innovative therapies to address neurodegenerative disorders, a deep understanding of the connection between immunity and neurological diseases is essential. With the advancements in these subject matters, we can pave the way to developing effective, safe, and targeted therapeutic strategies.

Keywords

Neuroinflammation, Neurodegenerative diseases, Immunotherapy, Gut-brain axis, Neuroimmune interactions, Emerging therapies.

Introduction

The immune system is a network of cells, tissues, and organs that defend the body against harmful pathogens. It plays a significant role in maintaining homeostasis of the body. Furthermore, it also helps in wound healing, tissue repair, and chronic inflammation, leading to cardiovascular disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer.[1]

Nowadays, neurotherapy is an emerging subject of interest in the medical sector. It has shown potential in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, dementia, depression, and anxiety.[2] The nervous system plays a crucial role in homeostasis of the body, and the disruption in the nervous system leads to various neurological disorders affecting overall health and well-being. Critical research on neurotherapy is essential to improving neurological disorders and treatment outcomes.[3]

Recent studies revealed that the immune system is linked to the nervous system. For understanding this relation, a concept of neuroimmunology has emerged to explore deep into the correlation between the nervous system and immune responses. Many neurological disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and parkinson’s disease, are now recognized to be caused by immunological dysfunction. Neuroinflammation is an important hallmark for various neurodegenerative diseases and is due to activation of immune cells within the central nervous system (CNS).[4] Chronic neuroinflammation can lead to progressive neuron loss, which in turn worsens these disorders. Therefore, a novel approach for the treatment of these disorders is to target the immune system.[5] Immune cells such as microglia and astrocytes are involved in learning and memory through the process called synaptic pruning. Dysregulation of this process leads to disorders such as autism and schizophrenia.[6] In addition, the gut-brain axis is another aspect to be considered in the immunity-neurotherapy intersection. The microbiota present in the gut is involved in the production of neurotransmitters, immune modulation, and metabolite release, which influences brain function. Many conditions, such as depression, anxiety, and neurodegenerative diseases, are linked with disruption in the gut microbiota.[7]

Neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative diseases

Neuroinflammation plays a vital role in a range of neurodegenerative diseases by causing damage within the CNS. The release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and other inflammatory mediators stimulates the immune cells, resulting in the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO). This ROS and NO cause oxidative stress and neuronal damage, leading to neuroinflammation. Subsequently, neuroinflammation can disrupt the blood-brain barrier (BBB), allowing peripheral immune cells to infiltrate the CNS. This further accelerates the inflammatory response, causing neurodegeneration. Research has shown that a toxic environment is created due to chronic activation of microglia and astrocytes, which leads to continuous loss of neurons and synapses. Thus, neuroinflammation is a driving force in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, parkinson’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.[8]

Alzheimer’s disease: Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by the accumulation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles made up of hyperphosphorylated tau protein. The progression of disease is seen due to the presence of significant neuroinflammation. Recent investigations on Alzheimer’s disease have shown that in response to Aβ plaques, microglial cells get activated, producing pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6). This cytokine exacerbates neuronal damage and contributes to the spread of tau protein throughout the brain.[9] Additionally, microglia are activated to clear Aβ plaques through phagocytosis, but due to insufficient clearance, sustained microglial activation takes place, and as a result, chronic neuroinflammation occurs.[10] The main multiprotein complex reported to cause neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease is the nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich–containing family, pyrin domain–containing–3 (NLRP3) inflammasome. The activation of this multiprotein complex within microglia releases IL-1β, which promotes inflammation and neuronal death.[11] Genetic studies to understand the correlation between neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease have shown the involvement of innate immune receptors, such as Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2), in modulating the microglial response to amyloid beta.[12]

Parkinson’s disease: Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative problem characterized by continuous loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. This leads to impaired motor symptoms such as tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia. Research studies have shown that neuroinflammation can contribute to parkinson’s disease. The presence of activated microglia in the substantia nigra confirms the role of neuroinflammation in parkinson’s disease. This leads to the production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, causing damage to dopaminergic neurons.[13] Additionally, the accumulation of alpha-synuclein, a protein that aggregates to form Lewy bodies in parkinson’s disease, can activate microglia and further propagate the inflammatory response.[14] An increased level of inflammatory cytokines in the blood of parkinson’s disease patients shows that systemic immune response may influence the CNS. Moreover, peripheral T-cells, which infiltrate the brain due to neuroinflammation, attack neurons expressing modified alpha-synuclein, contributing to neuronal loss and exacerbating the disease. Genetic investigations have identified several genes, such as leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) and Parkinsonism-associated deglycase 7 (PARK7), associated with parkinson’s disease. Any mutation to this gene can dysregulate the immune responses.[15] The role of the gut-brain axis in parkinson’s disease, where gut microbiota influences neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, adds another layer of complexity to understanding the immune response in parkinson’s disease.[16]

Multiple sclerosis: Multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune disease characterized by the attack of immune cells on the myelin sheath of the nerve fibers. This demyelination disrupts the transmission of electrical impulses in the CNS, resulting in motor weakness, sensory disturbances, and cognitive impairment. The pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis involves an immune response mediated by autoreactive T cells that recognize myelin as a foreign antigen and attack it. Further, it activates microglia and astrocytes, which leads to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines.[17] The recruitment of additional immune cells, including B cells and macrophages, due to an inflammatory response further contributes to myelin damage and neuronal loss.[18] The B-cell-mediated immune response in the CNS causes demyelination and plaque formation. The presence of oligoclonal bands in the cerebrospinal fluid reflects a B-cell-mediated immune response.[19] The immune cells in the blood are thought to be primed by molecular mimicry, where viral or bacterial antigens resemble myelin protein, leading to cross-reactivity. Environmental factors such as viral infections, vitamin D deficiency, and smoking are contributing factors in triggering or exacerbating the autoimmune response in multiple sclerosis.[20] Moreover, neuroinflammation also plays an important role in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Chronic inflammation in multiple sclerosis leads to irreversible disability.[21]

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is a neurological disorder characterized by the loss of motor neurons, which leads to muscle weakness, paralysis, and finally death. The exact mechanism of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is unknown, but one of the important features of this disease is neuroinflammation. Motor neuron degeneration activates the immune cells of the brain, which causes the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines that cause more damage to the motor neurons.[22]

Immune mechanisms in the brain

There are various specialized immune cells in the CNS that respond to injury or infection in the brain and maintain homeostasis. Some are discussed here:

Microglia: Are primary defensive macrophages that continuously maintain tissue integrity and clear debris via phagocytosis. When it encounters pathogens or injury, it gets activated and produces pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6. It also releases neurotrophic factors that support neuronal survival and repair. However, chronic microglial activation causes neuroinflammation and neuronal toxicity, and leads to neurodegenerative diseases.[23]

Astrocytes: Play an important role in maintaining the BBB, regulating neurotransmitter levels, and providing metabolic support to neurons. During neuroinflammation, reactive astrocytes are formed, which causes hypertrophy and the upregulation of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). It also participates in producing ROS, cytokines, and chemokines, which lead to neuroinflammation. Hence, it is another important glial cell in the brain that contributes to neurodegenerative diseases.[24,25]

Perivascular macrophages: Also perform immune surveillance in the CNS. It resides around blood vessels and helps to maintain BBB integrity. It facilitates adaptive immunity by presenting antigens to T cells. They are particularly responsible for conditions such as multiple sclerosis, where they contribute to the immune-mediated attack on the myelin sheath of the neurons.[26]

Tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM cells): Play a significant role in providing localized, long-term immunity after an initial infection. Recent studies have shown that they can rapidly respond to reinfection or reactivation of latent pathogens. The markers present on these cells are cluster of differentiation 69 (CD69) and CD103, which help exert an immediate effect. In viral infection, these cells are important in controlling the spread of the infection and viral reactivation in the CNS. Although they are involved in protective responses, their presence and activity could also exacerbate chronic inflammation, particularly in multiple sclerosis.[27]

B cells: Are mostly involved in humoral immunity. In the normal CNS, they are present in less number, mainly in the meninges and perivascular spaces. However, in disease states, it infiltrates the CNS and contributes to the immune-mediated attack on myelin, particularly in multiple sclerosis. Additionally, it also involves the production of antibodies, which form an immune complex and activate the complement system, which further damages myelin and neurons.[28]

Oligodendrocytes: Play a vital role in supporting neuronal function. However, recent research suggested that it also has immune functions. It participates in the immune response by interacting with microglia and astrocytes. The loss of oligodendrocytes has a significant effect on neuronal function and thus contributes to the progression of the disease.[29]

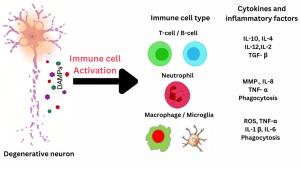

Figure 1: Damage–associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) are released in response to injury. Then, an innate immune response and infiltration of peripheral immune cells into the brain occur. This further leads to secondary brain injury, further destroying brain tissue and causing neurodegenerative diseases.[42]

Gut microbiota and neuroinflammation

The gut microbiota actively communicates with the CNS via a bidirectional communication network called the gut-brain axis. This network involves neural, endocrine, and immune pathways through which gut microbiota can influence brain function and behavior. Recent studies have shown that gut microbiota can modulate the immune response. They produce a wide range of metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which can cross the BBB, thus influencing the CNS function. For instance, butyrate has anti-inflammatory properties and can enhance the integrity of the BBB, thereby protecting the brain from inflammatory insults.[30] Therefore, dysbiosis of the gut microbiota can contribute to neurological disorders such as anxiety, depression, and Alzheimer’s disease.

Neurological disorders and gut microbiome: Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota has contributed to many mental health disorders. Neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease have also been linked to gut dysbiosis. In Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, there is an accumulation of amyloid-beta plaques and alpha-synuclein in the brain, respectively, due to dysbiosis. These findings suggest that by focusing on the gut microbiota, new therapeutic strategies can be developed that could be able to prevent or slow down the progression of neurodegenerative diseases.[31]

Microbiota-immune interactions and their effects on the brain: The gut microbiota plays a key role in shaping the population of immune cells in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). These immune cells, including regulatory T cells (Tregs) and dendritic cells, are essential for maintaining immune tolerance and preventing excessive inflammation.[32] The gut microbiota produces SCFAs, which modulate the function of Tregs and other immune cells. Thus, it protects against neuroinflammation. For example, butyrate has been shown to enhance the differentiation of Tregs, which helps in preventing excessive neuroinflammation.[33]

Neuroimmune interactions: Synapses and Neurotransmitters

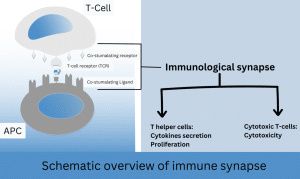

Immunological synapses and neural function: Immunological synapses are specialized junctions where immune cells communicate with each other and other cells for an immune response. In the CNS, immunological synapses are implicated in both protective and pathological immune responses. For example, in multiple sclerosis, the formation of immunological synapses causes the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and neurotoxic mediators, which in turn causes neurodegeneration. Conversely, under non-pathological conditions, these synapses can promote tissue repair and protection of the neurons by releasing neurotropic factors and clearing damaged cells.[34] Recent research has also shown the involvement of microglia, tissue-resident immune cells, in the formation of immunological synapses. Microglia-neuron interaction is important for synaptic pruning in the adult brain. Any problem in this interaction can cause neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease.[35,36]

Figure 2: T cell activation requires first engagement of the T cell receptor (TCR) with peptide-bound MHC II on the surface of argon plasma coagulation (APC). Ligand recognition causes the T cell to stop migration and to form an immune synapse with the corresponding APC.

Neurotransmitters and immune regulation: Serotonin or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), which is primarily known for regulating the mood, has also shown immunomodulatory effects in the context of immune regulation. Serotonin receptors are present in immune cells such as T cells and macrophages, thus responding to the serotonin signal. Depending on the receptor subtype activated, serotonin can have either pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory effects. For instance, activation of the 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors on T cells has been shown to reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and enhance inflammatory responses, respectively.[37,38]

Acetylcholine (ACh) is another neurotransmitter that helps in preventing excessive inflammation via the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. When ACh binds to the alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAChR) on macrophages, it inhibits the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6. This anti-inflammatory effect of ACh is crucial for maintaining immune homeostasis and preventing chronic inflammation.[39]

Acetylcholine also involves neuroprotection and can be a promising target for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. In neurotherapy, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) are used to treat Alzheimer’s disease. AChEIs may also exert immunomodulatory effects, as increased ACh levels can dampen neuroinflammation through the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway.[40]

Discusssion

Novel approaches in immunomodulation for neurotherapy

Innovative strategies in immunomodulation are emerging as promising approaches in neurotherapy.

CRISPR/Cas and gene therapy: Genetic mutation is one of the important reasons for neurodegenerative disorders. The CRISPR/Cas9 system enables precise gene editing. By correcting the mutated gene, neurological diseases can be treated. This technology is being explored for its ability to edit genes involved in neuroinflammation or neurodegeneration, with research underway on familial Alzheimer’s disease.[41]

Cell-based therapies: Stem cell therapy and adoptive cell transfer are two of the most promising approaches for the treatment of neurological problems. This novel approach is under investigation in neurotherapy. Stem cells can differentiate into neurons and glial cells; thereby, they have the potential to replace damaged cells in neurodegenerative disorders. In addition, adoptive cell transfer has been shown to suppress neuroinflammation in conditions such as multiple sclerosis.[42]

Nanomedicine: Nanomedicines are another novel therapeutic strategy to deliver drugs specifically to the CNS. Nanoparticles and nanocarriers can deliver the drug to the targeted site, thus enabling targeted modulation of immune responses and reduction of neuroinflammation.

Biologics and small molecules: This novel approach, where biologics like monoclonal antibodies, which target specifically cytokines or immune checkpoints, and small molecules that modulate immune cell activity are under investigation. This therapeutic strategy offers targeted treatment options for neurodegenerative diseases.

Future research directions

To advance neurotherapy and improve patient outcomes, several research areas warrant attention:

Clinical trials: A rigorous clinical trial should be conducted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the immunotherapeutic approaches. The trial must target a diverse range of patients with long-term pharmacovigilance to assess the safety and effectiveness of the novel neurotherapeutic drugs.

Personalized medicine: Research on pharmacogenomics and biomarker discovery is crucial to tailoring individualized patient therapy. It can enhance the treatment outcomes and reduce adverse effects.

Mechanistic studies: Research should be conducted to get in-depth insight into the mechanisms underlying the interaction between the brain and the immune system, along with understanding the efficacy of new therapies on these interactions.

Translational research: Collaborative efforts between researchers, clinicians, and industry partners can help bridge the gap between preclinical findings and clinical applications of novel therapies.

Integration of multi-omics approaches: Utilizing multi-omics approaches, including genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, can provide comprehensive insights into disease mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Integrating these approaches into research and clinical practice may enhance the development of targeted and effective neurotherapies.

Conclusion

This review has explored the role of the immune system in neurological health and disease conditions. Chronic neuroinflammation is the main feature of neurodegenerative diseases, causing neuronal damage and disease progression. The role of immune cells in neuroinflammation helps researchers develop novel therapies for the treatment of neurological diseases. Moreover, the influence of gut microbiota in immune responses through the gut-brain axis is another key area to be explored to design a new treatment approach in neurotherapy. Understanding neurotransmitters and immunological synapse (IS) can aid in developing targeted therapies that modulate both immune and neural functions. In the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders, CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, cell-based therapies, and nanomedicine also open a new avenue for researchers as an emerging therapy. By targeting specific immune mechanisms, it offers the potential to improve disease outcomes, personalize treatment, address the unmet needs of the neurological patient, and improve therapeutic options. The integration of immune-based approaches into neurotherapeutic strategies has the potential to revolutionize the management of neurodegenerative diseases by enhancing therapeutic efficacy, reducing side effects, and providing long-term benefits to the patient.

References

- Abbas AK, Lichtman AH. Basic Immunology: Functions and Disorders of the Immune System. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017 Basic Immunology

- Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM. Principles of Neural Science. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013 Principles of Neural Science

- Ransohoff RM. How neuroinflammation contributes to neurodegeneration. Science. 2016;353(6301):777-783 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Heneka MT, Carson MJ, El Khoury J, et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(4):388-405 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bilbo SD, Schwarz JM. The immune system and developmental programming of brain and behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2012;33(3):267-286 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behavior. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(10):701-712 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ransohoff RM, Perry VH. Microglial physiology: Unique stimuli, specialized responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:119-145 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Heneka MT, Carson MJ, El Khoury J, et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(4):388-405 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Heppner FL, Ransohoff RM, Becher B. Immune attack: The role of inflammation in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(6):358-372 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Heneka MT, Golenbock DT, Latz E. Innate immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(3):229-236 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bilbo SD, Schwarz JM. The immune system and developmental programming of brain and behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2012;33(3):267-286 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behavior. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(10):701-712 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ransohoff RM, Perry VH. Microglial physiology: Unique stimuli, specialized responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:119-145 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Heneka MT, Carson MJ, El Khoury J, et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(4):388-405 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Heppner FL, Ransohoff RM, Becher B. Immune attack: The role of inflammation in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(6):358-372 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Heneka MT, Golenbock DT, Latz E. Innate immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(3):229-236 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Keren-Shaul H, Spinrad A, Weiner A, et al. A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2017;169(7):1276-1290.e17 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hirsch EC, Hunot S. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease: A target for neuroprotection? Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(4):382-397 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lee HJ, Bae EJ, Lee SJ. Extracellular alpha-synuclein-a novel and crucial factor in Lewy body diseases. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(2):92-98 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kannarkat GT, Boss JM, Tansey MG. The role of innate and adaptive immunity in Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2013;3(4):493-514 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sampson TR, Mazmanian SK. Control of brain development, function, and behavior by the microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17(5):565-576 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Frohman EM, Racke MK, Raine CS. Multiple sclerosis-The plaque and its pathogenesis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(9):942-955 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hauser SL, Oksenberg JR. The neurobiology of multiple sclerosis: Genes, inflammation, and neurodegeneration. Neuron. 2006;52(1):61-76 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lucchinetti CF, Popescu BF, Bunyan RF, et al. Inflammatory cortical demyelination in early multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2188-2197 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ascherio A, Munger KL. Environmental risk factors for multiple sclerosis. Part II: Noninfectious factors. Ann Neurol. 2007;61(6):504-513 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mahad DH, Trapp BD, Lassmann H. Pathological mechanisms in progressive multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(2):183-193 PubMed| Crossref | Google Scholar

- Philips T, Robberecht W. Neuroinflammation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Role of glial activation in motor neuron disease. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(3):253-263 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ransohoff RM, Perry VH. Microglial physiology: Unique stimuli, specialized responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:119-145 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sofroniew MV, Vinters HV. Astrocytes: Biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119(1):7-35 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Witte ME, Geurts JJ, de Vries HE, van der Valk P, van Horssen J. Mitochondrial dysfunction: A potential link between neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration? Mitochondrion. 2010;10(5):411-418 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mildner A, Schmidt H, Nitsche M, et al. Microglia in the adult brain arises from Ly-6ChiCCR2+ monocytes only under defined host conditions. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(12):1544-1553 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Smolders J, Remmerswaal EB, Schuurman KG, et al. Characteristics of differentiated CD8+ and CD4+ T cells present in the human brain. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(4):525-535 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hauser SL, Oksenberg JR. The neurobiology of multiple sclerosis: Genes, inflammation, and neurodegeneration. Neuron. 2006;52(1):61-76 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Brambilla R, Bracchi-Ricard V, Hu WH, et al. Inhibition of astroglial nuclear factor kappaB reduces inflammation and improves functional recovery after spinal cord injury. J Exp Med. 2005;202(1):145-156

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Dalile B, Van Oudenhove L, Vervliet B, Verbeke K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:231 PubMed | Google Scholar

- Vogt NM, Kerby RL, Dill-McFarland KA, et al. Gut microbiome alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2017;7:13537 PubMed| Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(43):16731-16736 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504(7480):446-450 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Dustin ML. The immunological synapse. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2(11):1023-1033

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Prinz M, Priller J. Microglia and brain macrophages in the molecular age: From origin to neuropsychiatric disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(5):300-312 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kettenmann H, et al. Microglia: New roles for the synaptic stripper. Neuron. 2013;77(1):10-18 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Baganz NL, Blakely RD. A dialogue between the immune system and brain, spoken in the language of serotonin. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2013;4(1):48-63 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Shajib MS, Khan WI. The role of serotonin and its receptors in activation of immune responses and inflammation. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2015;213(3):561-574 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rosas-Ballina M, Tracey KJ. The neurology of the immune system: Neural reflexes regulate immunity. Neuron. 2009;64(1):28-32 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. Neural regulation of immunity: Molecular mechanisms and clinical translation. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20(2):156-166 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gaj T, Gersbach CA, Barbas CF. ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2013;31(7):397-405 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Singer NG, Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells: Mechanisms of inflammation. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2011;6:457-478 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Finger CE, Moreno-Gonzalez I, Gutierrez A, Moruno-Manchon JF, McCullough LD. Age-related immune alterations and cerebrovascular inflammation. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(2):803-818

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

None

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Sannu Ahmed

Department of Pharmacy

National Academy for Medical Sciences, Old Baneshwor, Kathmandu, Nepal

Email: pr.sannu.ahmed@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Pradip Regmi

Department of Pharmacy

Nepal Institute of Health Sciences, Jorpati, Kathmandu, Nepal

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Not reported

Guarantor

Not reported

DOI

Cite this Article

Sannu A, Pradip R. The Role of Immunity in Neurodegenerative Disease: A Literature Review. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(3):e3062251. doi:10.63096/medtigo3062251 Crossref