Author Affiliations

Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a worldwide health emergency, accounting for millions of deaths every year. 7–10% of community antibiotic prescriptions are from dentistry, frequently in contexts where operative management would be preferable. This misuse speeds up resistance, drives up the costs of healthcare, and puts patients at avoidable risk. Antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) within dentistry is therefore paramount to achieve rational prescription. Core principles of AMS include choosing the appropriate drug, dose, and duration while reducing undesirable outcomes and maintaining antibiotic effectiveness. Recommendations are made to prioritize dental interventions like extraction, root canal, or drainage, with antibiotic use limited to systemic infection or high-risk individuals. Successful AMS strategies involve professional education, audit with feedback, guideline dissemination, and application of digital decision-support systems. Patient education and engagement with physicians and pharmacists also support stewardship activities. The following barriers, however, impede the way forward: poor adherence, constraints of resources, limited IT infrastructure, and patient demand. There is a need for sustainable policies, ongoing professional development, and strong surveillance frameworks to bridge AMS into established dental practice.

Keywords

Antimicrobial resistance, Dentistry, Antimicrobial stewardship, Rational prescribing, Patient safety, Guidelines.

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance is a significant threat to global public health and development. In 2019, bacterial AMR was linked to roughly 4.95 million deaths, with about 1.27 million deaths directly caused by it.[1] This shows that resistant infections significantly impact global mortality and disability. Projections suggest that AMR-related deaths could rise considerably if current trends continue.[2]

AMS aims to optimize antimicrobial therapy selection, dosage, method, and duration to enhance patient outcomes while minimizing resistance.[3] Recognizing international and national dental organizations (like the Fédération Dentaire Internationale [FDI] World Dental Federation and the American Dental Association) and public health entities have promoted dental AMS principles. Pilot antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) in dental settings have shown that education, guideline implementation, and decision support tools can significantly reduce inappropriate prescriptions. Recent reviews confirm that stewardship interventions in dental settings can greatly reduce inappropriate prescribing.[4] By identifying areas where stewardship is most needed and which interventions have proven effective, this review seeks to help clinicians, policymakers, and researchers integrate AMS principles into standard dental care.

Overview of AMS: AMS involves a structured approach to promote the cautious use of antimicrobials. This includes coordinated efforts to ensure access to effective treatments, enhance patient outcomes, and minimize AMR.[5]

According to the guidelines established, the primary objectives are:

- Improving patient health outcomes by ensuring the safe and effective use of antimicrobials.

- Reducing antibiotic resistance through responsible prescribing practices.

- Minimizing harm and unnecessary expenses, such as adverse drug reactions and Clostridioides difficile [6]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines particular stewardship goals, such as effectively treating illnesses, safeguarding patients from damage, and managing antibiotic resistance.[6]

CDC core elements (Outpatient): The CDC identifies four key components for outpatient stewardship:

- Commitment: Demonstrate leadership commitment.

- Action for policy and practice: Implement prescribing policies based on evidence.

- Tracking and reporting: Monitor prescribing practices and provide feedback.

- Education and expertise: Educate providers and patients and ensure access to stewardship expertise.[7]

Global initiatives and One Health: The One Health approach emphasizes the need to address AMR across human, animal, and environmental sectors. The FDI World Dental Federation, for example, promotes the integration of stewardship into dental practice, highlighting the importance of surveillance, guideline development, and education for all stakeholders.[8]

World Health Organization (WHO): The WHO offers general stewardship frameworks and tools, such as the AWaRe antibiotic classification, to promote the rational use of antibiotics, but it does not provide specific guidelines for dental practice. The AWaRe system categorizes antibiotics into Access, Watch, and Reserve groups to support global stewardship strategies.

World Dental Federation (FDI): Defines antibiotic stewardship in dentistry as coordinated efforts to encourage appropriate antibiotic use and support sustainable therapeutic access. Encourages dental professionals to stay informed about AMR, align their prescribing practices with the best available evidence, and implement stewardship policies that include infection control measures. Strongly supports national dental associations (NDAs) in developing stewardship plans and educating both practitioners and patients.[8]

Antimicrobial use and misuse in dentistry

Amoxicillin remains the foundational antibiotic for odontogenic infections, especially when combined with metronidazole to address anaerobic pathogens. A recent German study (2025) found that among dental antibiotic prescriptions, amoxicillin accounted for 54.2%, amoxicillin-clavulanate for 24.5%, and clindamycin for 21.0%, with a high clindamycin usage despite known safety concerns.[9]

Antibiotics are indicated for systemic involvement, such as fever, spreading infection, cellulitis, systemic signs, or where local surgical and operative care cannot be performed immediately.[10] Studies reveal frequent overprescribing, with antibiotics often given for non-indicated conditions, e.g., pulpitis, localized abscesses, and for longer durations (7 to 10 days) instead of the recommended 3 to 5 days or a single preoperative dose.[11] Major guidelines, including those from the American Dental Association (ADA), emphasize local treatment as the primary approach and antibiotics only for select high-risk situations.

- High prevalence of inappropriate use: Systematic reviews report that over 70-90% of dental antibiotic prescriptions in some regions are not guideline-compliant.

- Unnecessary prophylaxis: Large U.S. datasets show that most antibiotics prescribed before dental visits were given to patients without guideline-defined risk factors.[12]

| Antibiotic | Class | Typical Dental Indications | Typical Adult Dose (oral) | Typical Duration (dental practice) |

Guideline

|

| Amoxicillin | Aminopenicillin (β-lactam) | First-line for odontogenic infections, periapical abscesses, and prophylaxis | 500 mg TDS | Usually 3–7 days; review at 48–72 h | Preferred first-line as per the American Dental Association

|

| Penicillin V | Narrow-spectrum penicillin | Alternative first line for odontogenic infections | 500 mg QID | Typically, 5 days

|

Similar indications to Amoxicillin

|

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate (Co-amoxiclav) | β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor | Odontogenic infections, failed monotherapy, severe infections | 625 mg BD | 5–7 days | Use the lowest dose available.

|

| Metronidazole | Nitroimidazole | Anaerobic oral infections: often combined with amoxicillin | 400–500 mg TDS | 5–7 days | Avoid alcohol; useful as an adjunct to β-lactam

|

| Clindamycin

|

Lincosamide | Alternative for penicillin-allergic patients (non-anaphylactic) or for some severe infections | 300–450 mg TDS | 5–7 days

|

Reserve for true penicillin allergy (or when indicated)

|

| Azithromycin

|

Macrolide | Alternative in penicillin-allergic patients | 500 mg once daily | 3–5 days depending on regimen

|

Interactions with other drugs increase resistance; use judiciously.

|

| Doxycycline

|

Tetracycline

|

Used for periodontal infections, sometimes as an adjunct in periodontal therapy

|

100 mg BD

|

Varies

|

Not for children <8 years or pregnant; photosensitivity risk

|

Table 1: Commonly prescribed antibiotics in dentistry with their typical indications, doses, and durations based on guideline recommendation

Therapeutic misuse: Cochrane reviews show that systemic antibiotics have little to no benefit for disorders such as irreversible pulpitis or symptomatic apical periodontitis when competent endodontic therapy is offered; yet, antibiotics are still often administered.[13]

Regional variation: Studies from countries such as India, the UAE, and Pakistan also demonstrate indiscriminate prescribing and wide variability in regimens.[14]

Consequences of inappropriate antibiotic use: Inappropriate antibiotic use, such as unnecessary prescriptions, incorrect drug/dose/duration, and misuse in non-humans, accelerates the selection of resistant bacteria. At the population level, this drives higher mortality and complicates routine care such as surgery, chemotherapy, and intensive care. Updated 1990-2021 analysis shows 1.14 million attributable deaths and the greatest rise among adults ≥ 70 years since 1990.[15]

Mechanistically, misuse expands the “resistome” (reservoir of resistance genes) in humans, animals, and the environment. In Asia, particularly India, the misuse and overuse of antibiotics have led to a significant increase in drug-resistant bacterial strains, posing a major public health challenge. In Bangladesh, resistance rates are particularly alarming: 60 to 70% of Escherichia coli are resistant to third-generation cephalosporins and ≥80% to fluoroquinolones, while Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) prevalence stands at 40–50%.[15]

Any antibiotic can cause side effects like allergies, anaphylaxis, rash, gastrointestinal toxicity, QT prolongation, and cytopenia. U.S. surveillance shows 13.7% of adult Emergency Department (ED) visits for adverse drug events are antibiotic-related; in broader estimates, antibiotics account for 1 in 5 drug-related ED visits across all ages. In children, there were about 69,000 ED visits per year from 2011 to 2015, most of which were due to allergic reactions to these antibiotics. A particularly severe harm is Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) after antibiotic exposure. Recent case-control data rank clindamycin and later generation cephalosporins as the highest risk, while doxycycline/minocycline are lower risk. Preventing unnecessary exposure is therefore a key safety strategy.[16]

Antibiotics disrupt the gut microbiome, causing dysbiosis by reducing microbial diversity, eliminating beneficial fermenters such as butyrate-producing bacteria, and promoting blooms of pathobionts like Enterobacteriaceae. Classic longitudinal studies show that recovery is often incomplete months after therapy, with individual-specific trajectories, even after short courses; some microbiomes fail to recover by 6 months.

Recovery is variable across individuals: some cohorts regain near baseline community structure within 6 weeks, but persistent species-level losses and metabolic functions change are common. Modeling suggests that certain regimens can push the microbiome into long-term alternative stable states, not a complete restoration. In one study, ciprofloxacin reduced Escherichia coli and Bifidobacterium, with some species requiring up to one year for recovery. Likewise, disruption of the urogenital microbiome may increase infection risk in vulnerable groups.[17] Maintaining microbial eubiosis across body sites is therefore a key principle of AMS, underscoring the need to prescribe antibiotics only when clearly indicated.[17] Beyond mortality, AMR and antibiotic harms impose substantial health system and societal costs.

Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines:

Antibiotic prescribing in the dental field should be oriented toward definitive dental treatment (DCDT) and limit antibiotics to obviously indicated situations, with use of the narrowest appropriate agent for the briefest appropriate period. The ADA 2019 evidence-based guideline for pulpal and periapical diseases discourages routine use of antibiotics in most immunocompetent adults with dental pain or local swelling if DCDT is present, with reassessment in 3 days and discontinuation 24 hours after resolution of symptoms (resulting in short courses).[18] CDC/ADA chairside materials reinforce these recommendations and highlight urgent referrals for sepsis or deep-space infection. Narrative and comparative overviews emphasize that most dental infections are optimally treated operatively, and that excess precipitates resistance and side effects, backing stewardship and aligned, guideline-driven care.[19] Global guidelines (e.g., UK Faculty of Dental Surgery 2020) also dictate first-line penicillin, prefer brief courses (≤5 days), and warn against broad-spectrum drugs except where clearly needed.[20]

Prophylaxis during dental procedures:

Infective endocarditis (IE): Contemporary prevention of IE is shifting from blanket prophylaxis to directed prophylaxis for the highest-risk cardiac patients and sound oral hygiene. The American Heart Association (AHA) 2021 scientific statement outlines that, in the case of dental procedures with gingival manipulation, prophylaxis is indicated only for prosthetic valve or repair material, previous IE, some congenital heart disease, and cardiac transplant with valvopathy; oral health is more critical than a dose of an antibiotic. AHA wallet guidelines also highlight that only a small proportion of IE cases are potentially avoidable by prophylaxis and limit prophylaxis to the highest-risk individuals.[21] Current guidelines agree and urge oral stewardship with respect to IE prophylaxis and prosthetic joints, combining AHA/ADA/IDSA recommendations.[22]

Adults should take 2 g of amoxicillin orally 30 to 60 minutes before the dental operation as a preventative measure. For penicillin-allergic patients with documentation of allergies, alternative use can be made of azithromycin 500 mg, with clindamycin being less commonly prescribed due to its link with a greater risk of Clostridioides difficile infection.[21]

Prosthetic joint infections (PJI): The ADA (2015) clinical practice guideline saw no correlation between dental surgery and PJI and does not endorse routine prophylaxis in most patients with prosthetic joints; consider case-by-case in only highly selected, medically complicated patients following consultation with the orthopedic surgeon.[23,24] Prophylaxis in dentistry reviews also identify past overuse and call for individualized decision-making rather than routine prescribing.[25]

Therapeutic use for dental infections:

Pulpal and periapical disease: For symptomatic irreversible pulpitis, apical periodontitis, and localized acute apical abscess, definitive dental care (e.g., pulpotomy, root canal therapy, drainage) is prioritized. Antibiotics provide minimal added value and are reserved for cases with systemic compromise (fever, malaise, lymphadenitis), extension of infection, or high-risk host.[26] If antibiotics are warranted, amoxicillin should be used as the first-line agent; metronidazole may be added if anaerobic coverage is required; Macrolides and fluoroquinolones should be avoided except in allergy/resistance or unusual microbiology.[23] Global narrative reviews again stress limiting indications and highlight that widespread prescribing continues in the face of guidance, highlighting the disconnect between practice and evidence.[27]

Periodontal and peri-implant disease: Systemic antibiotics are adjuncts, not alternatives, for mechanical debridement. They should be reserved for aggressive/refractory periodontitis or cases with acute systemic signs (e.g., cellulitis) and apply narrow-spectrum combinations (e.g., amoxicillin ± metronidazole). According to local guidelines, we should omit routine courses following uncomplicated scaling/root planning.[28,29]

Oral surgery and third molars: There is evidence of limited or procedure-specific prophylactic benefit; routine post-extraction antibiotics are not normally required in healthy patients. When prophylaxis is applied (e.g., high risk of infection, extensive bone surgery, immunocompromise), utilize short durations and critically review the need to avoid resistance and side effects.[30,31]

Dose optimization and duration of therapy: Principles across guidelines are:

- Use shortest effective duration (typically 3–5 days)

- stop 24 h after symptom resolution

- re-assess within ~72 h

- not to use broad-spectrum agents unless required by clinical severity or culture.

First-line options continue to be phenoxymethylpenicillin or amoxicillin; reserve metronidazole for anaerobes or amoxicillin-clavulanate for severe spreading infection; use clindamycin with caution in consideration of CDI risk and increasing resistance patterns.[31]

AMS approaches in dentistry:

Education and training of dental professionals: Integrating AMS into undergraduate education, house-officer training, and CPD significantly enhances the quality of dental prescribing. In a combined clinical audit and workshop dental course, prescribing in accordance with national guidelines increased from 19% to 79%, and total prescription errors decreased from 23% to 9% in 12 months.[33] Targeted digital education can enhance these gains. One new scholarly-clinical collaboration developed the ‘dentalantibiotic.com’ decision guide and tested it in learners and dentists: users of the app had higher scores on pharmacology exams and found it helpful for daily antibiotic decisions. (The study shows higher mean scores in the app group and enhanced confidence.)[34,35]

Audit and feedback mechanisms: Audit–feedback in dentistry works both in trials and in day-to-day quality improvement:

- RAPiD cluster RCT (Scotland): targeted feedback to GDPs reduced antibiotic prescribing rates by 5.7% compared with control based on normal NHS data.[36]

- Future clinical audit (England): an education + audit multi-practice program decreased unnecessary prescriptions and corrected dose accuracy from 43% to 78%.[37]

Recent systematic reviews reaffirm audit, education, and guideline overviews as reliably effective levers for decreasing dental antibiotic excess use and enhancing rational choice.[38]

Decision support tools and mechanisms: Chairside support (digital pathways, embedded guideline prompts) is now more palatable to dentists and can normalize indications, agents, dose and duration. Qualitative and mixed-methods research demonstrates moderate confidence among trainees for antibiotic choices and cites CDS and structured pathways as preferred supports; apps such as dentalantibiotic.com execute this at the point of care.[39]

Patient education and engagement: Patient expectation is a recognized driver of ambulatory care unnecessary antibiotics, and dentistry is not different. Realistic solutions such as short counseling, printed information, and short videos are suggested components of outpatient stewardship strategies and dental toolkits, to reset expectations and decrease demand for “quick-fix antibiotics.” Education integrated into multi-component dental ASPs (with protocols and feedback) has also translated into significant improvements in proper use in private offices.[40,41]

Interdisciplinary working with pharmacists and physicians: Engaging pharmacists in dental practice integrates real-time scrutiny of allergy pathways, drug–drug interactions, renal dosing, and duration particularly for medically complex patients:

- Pharmacist-driven, multi-perspective ASP (Japan, university dental hospital): real-time prescriber feedback, student teaching, and formulary optimization altered dentists’ prescribing patterns across several drug classes.[42]

- Dental ASP implementation (U.S. academic dental urgent-care): a multimodal program based on CDC Core Elements yielded an ~73% relative decrease in urgent-visit antibiotic prescribing (8.5% to 2.3%, P<.001).[42]

Narrative and scoping reviews of dentistry also feature pharmacist–dentist collaboration as a high-yield strategy for stewardship results and drug safety.[43]

Narrow-spectrum antibiotic use and delayed prescribing: Dental stewardship prioritizes treatment with procedures initially (e.g., debridement, drainage) and then reserves antibiotics for systemic infection or certain indications, and when they are used, narrow-spectrum drugs, appropriate doses, and the shortest effective courses are to be used. The updated Antimicrobial Prescribing in Dentistry Good Practice Guidelines (3rd ed.) from the College of General Dentistry/FDS present condition-specific tables clearly and support selective prescribing; and delayed prescriptions are also addressed where clinically appropriate (e.g., where observation for progression is possible.[44,45]

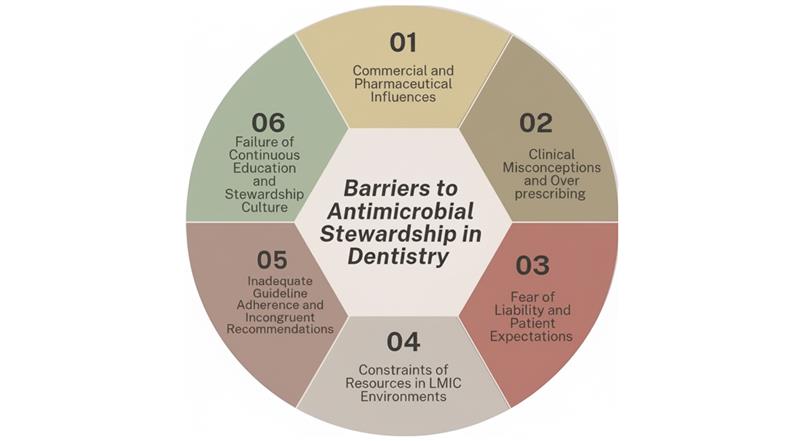

Barriers to successful AMS in dentistry:

Inadequate guideline adherence & incongruent recommendations: Providers of dental care are often presented with incongruent guidelines or clinical ambiguity. The Minnesota survey of dentists demonstrated that 44% reported conflicting provider guidelines, and another 44% stated conflicting scientific evidence as a major barrier to guideline adherence. Additionally, dentists tend to prescribe prophylactic antibiotics in situations not supported by guidelines, such as prosthetic joints or controlled diabetes, showing a guideline-practice discrepancy.[46]

Fear of liability & patient expectations: Prescribing habits are significantly shaped by fear of liability. A qualitative analysis revealed that dentists tend to respond to patients’ expectations, particularly if they think a physician recommended prophylaxis without checking, just to prevent legal action. They also often write “just in case” antibiotics for future travel or because they themselves will be absent, resulting in unwarranted prescriptions. Moreover, pressures of satisfaction, fear of patient loss, or harm to online reputation can also propel dentists to overprescribe.[47]

Limited access to evidence-based resources and support tools: Dental clinicians usually have insufficient real-time, evidence-based decision support. A pre-implementation survey revealed that dentists depended on anecdotal experience; they gave in to physicians’ recommendations, had poor access to evidence-based information, and had a high interest in clinical decision-support tools (CDSTs) to inform antibiotic prescribing. Confidence was affected by levels of training but not by actual prescribing knowledge, reflecting the requirement for systematic support.[48]

Inadequate IT infrastructure and data support: Even though most of the literature addresses hospital environments, it indicates that infrastructure deficiencies, such as IT and diagnostics, hinder AMS. A dearth of health IT hampers monitoring, auditing, and enacting stewardship strategies. Such constraints are probably present in dentistry, too, especially in environments that lack integrated electronic health records or prescribing monitoring systems.[49]

Absence of governance, enforcement, and institutional support: In health care facilities in general, inadequate enforcement of stewardship policies and weak organizational support weaken stewardship programs. In Saudi hospitals, for instance, poor policy enforcement, fragmentation of the team, communication problems, and staff shortage were key impediments to AMS implementation.[49] In Pakistan, AMS programs are hindered by weak administrative support, the absence of accreditation standards, and inadequate infrastructure, which erodes long-term sustainability. Within dental settings, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), there is limited leadership and governance of AMS that probably reflects these same limitations.[50]

Constraints of resources in LMIC environments: LMICs often do not have basic laboratories and logistical facilities. Research has indicated that obstacles such as sub-optimal diagnostic capabilities, insufficient microbiology support, restricted antimicrobial availability, and weak governance mechanisms hamper AMS activities. While such studies tend to focus on hospital environments, in dentistry and especially in less-resourced settings, such structural shortfalls most likely equate to limited AMS capacity.[51]

Commercial and pharmaceutical influences: In the veterinary sector, professionals report that pharmaceutical industry pressure and poor regulation drive excessive use of antibiotics. While this is beyond dentistry, the marketing power of the pharmaceutical industry and lack of enforcement of prescribing laws could, in the same way, impact dental antibiotic prescribing practices, particularly where promotional campaigns target private practitioners or unregulated markets.[52]

Clinical misconceptions & overprescribing: There are still misconceptions regarding antibiotic necessity. For instance, most dentists have prescribed antibiotics for self-limiting or non-indicated conditions such as gingival pain (38%), upcoming vacations (38%), or legal issues (24%). This implies a larger trend of overprescription by misestimation instead of clinical necessity.[53]

Patient misunderstanding and demand: While dental literature is not necessarily in-depth here, more general evidence points to how patient misunderstanding wanting antibiotics for trivial complaints encourages prescribing. Public unawareness plays a large role in overuse. While this might be less overtly so in dentistry, the same principle holds that patients perceive antibiotics as stopgaps, putting pressure on professionals.[54]

Failure of continuous education and stewardship culture: Finally, stewardship sustainability hinges on education, audits, and organizational culture. Research emphasizes that repeated training, e-learning, audits, and feedback can enhance guideline adherence (e.g., from 19% to 79% compliance between audited cycles). Without this ongoing educational infrastructure and culture, stewardship fails.[55]

Figure 1: Key challenges to implementing effective antimicrobial stewardship in dentistry

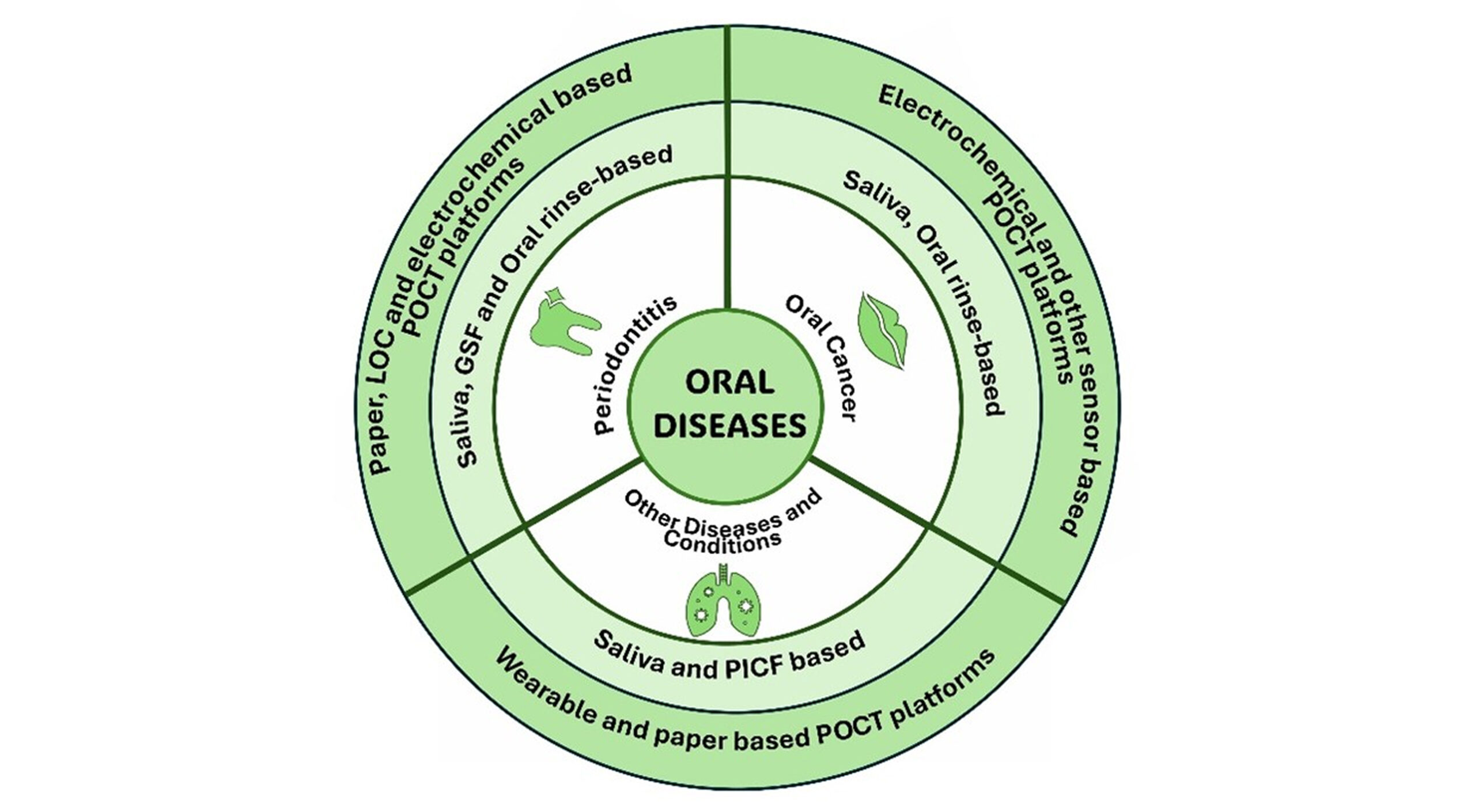

Electronic & technological equipment assisting AMS in dentistry:

Point-of-Care Tests (POCTs) in dental practice: While POCTs such as C-reactive protein (CRP) testing are not yet routine in dentistry, primary care research illustrates their potential to decrease empirical antibiotic prescribing by assisting clinicians in making distinctions between bacterial and viral or self-limiting infections. A systematic review estimated that CRP-POCT decreased immediate antibiotic prescribing by approximately 21%, with effects persisting in the long term and no effect on recovery outcomes.[56] A Northern England cluster randomized controlled trial had a ~21% reduction in antibiotic prescribing for acute cough consultations through CRP-POCT. Qualitative feedback additionally demonstrates that clinicians feel more confident in refusing antibiotics when a negative CRP result underpins their decision.[57]

For oral infections like localized abscesses or early-stage cellulitis, a dental chairside CRP or similar biomarker test could significantly reduce unnecessary antibiotic use, especially when clinical signs suggest viral or non-infectious etiologies. Limitations include test cost, equipment availability, and reimbursement models, mirroring barriers experienced in primary care.[58]

Figure 2: Schematic overview of oral diseases and their diagnostic approaches using POCT platforms, highlighting saliva, gingival crevicular fluid (GCF), oral rinse, and peri-implant crevicular fluid (PICF) as key biofluids for detection

Electronic health records (EHRs) & prescription monitoring: Integrated EHR systems with antibiotic prescription modules allow tracking of antibiotic history, dose, and duration, and can also notify deviation from guidelines. Though direct dental studies are scant, more general AMS models focus on EHR-based surveillance and clinical decision support software to identify non-compliant prescriptions and enable feedback loops. A dental EHR might signal clinicians when a prescription is beyond recommended duration or when a broad-spectrum agent is prescribed unjustifiably, eliciting reconsideration or consultation with stewardship guidelines.[59]

Tele-dentistry and AMS: Tele-dentistry may serve as a stewardship key by facilitating remote triage, evaluating symptom severity, and recommending when there is a need for in-person care (e.g., for procedures), preventing unnecessary prophylactic antibiotic prescriptions. This model was invaluable during the COVID-19 pandemic and other public health emergencies by limiting avoidable visits and conserving antibiotic use for proven needs. Online consultations can enable dentists to give self-care guidance or follow up on cases periodically, preventing default antibiotic prescription if patients can’t be seen in clinics in person.[60]

Artificial Intelligence (AI) integration in stewardship: AI and machine learning (ML) hold promise to enhance AMS by examining patterns in large data sets to make predictions about resistance, recommend empiric antibiotic selection, and tailor dosing. Systematic review across settings of healthcare concluded that AI could improve empirical antibiotic selection and compliance with stewardship guidelines. In dentistry, AI might systematically scan patient history (e.g., comorbidities, antibiotic exposure history) and oral images (e.g., radiographs) and suggest narrow-spectrum agents or flag stewardship-concordant options. Trust from the clinician and interpretability are key; evidence in other fields indicates that although confidence can be instilled by AI recommendations, acceptance will rely on transparency. Ethical frameworks should also be included to facilitate decision-making in uncertain clinical situations.[61]

Case Studies

To combat AMR, a variety of AMS interventions have been established in different nations.

UK (NHS programs): Using a realism implementation approach, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) and the National Health Service England (NHSE) launched a nationwide rollout of TARGET (Treat Antibiotics Responsibly, Guidance, Education, and Tools) AMS training in October 2022 (Ashiru-Oredope & Hopkins, n.d.).A comprehensive analysis of 23 research studies (1997–2023), including pre–post and randomized controlled trials, evaluated the effects of interventions, including audit, education, and feedback, on dentists’ prescription practices for antibiotics. When taken as a whole, these initiatives reduced the incorrect prescription of antibiotics by 70%.[62]

USA: In 2019, the ADA released guidelines suggesting that antibiotics be prescribed carefully to treat tooth discomfort and swelling.[63,64] Despite various restrictions, dentists continued to prescribe antibiotics. Antibiotic use in outpatient settings decreased overall, but between 2020 and 2022, dentists prescribed more antibiotics than any other group, accounting for almost 10% of all outpatient prescriptions. This increase may have been caused by the spread of COVID-19.[64] Because of the lack of clinical expertise, data from LMIC indicate that antibiotic use has increased over time. Raising professional and public knowledge of the dangers of antibiotic usage is crucial, as is creating AMS programs and inspection procedures.

Lessons learned from implementation: The UK’s NHS TARGET program achieved a 70% reduction in incorrect dental antibiotic prescribing, demonstrating how effective AMS significantly improves prescribing behavior by combining clinical audit, education, feedback, and clear rules.[65] While significant high-income countries, sub-themes proved more specific and precise, such as mandatory enforcement, various profiles, and staff required for excellent management and appropriate design, LMIC sub-themes demonstrated that money and surveillance remained crucial challenges for interventions.[66] Addressing AMR has become more difficult because of the COVID-19 epidemic and the alterations it has caused in the healthcare system. Recent data indicated a modest increase in dental prescriptions, particularly in LMICs, even though community antibiotic use had reduced in the early phases of the pandemic. This suggests that present AMS efforts need to be strengthened.[67]

Future directions and research priorities:

Innovations in antimicrobial development: The rising AMR concerns require immediate attention. For this, a variety of drug delivery methods are being created. Localized antimicrobials, such as chlorhexidine encapsulated in nanoparticles (Nano-CHX), are recent developments. These have demonstrated strong in-vitro efficacy against oral biofilms, providing promising oral cavity anti-biofilm techniques.[68,69] Phage therapy, which incorporates bacteriophages to break down dental biofilms, is another focused strategy currently being employed.[70] Visible-light trigger systems are one of the innovations in smart medicine delivery systems. These methods use a double-layered stack of TiO₂ nanotubes to deliver antibiotics in a regulated manner.[71]

Behavioral change interventions: Both patient-focused and dentist-focused activities are used in behavioral change strategies. Prescription audits, feedback, and continuous education are dentist-focused tactics that greatly lower antibiotic abuse. A prospective cohort study involving weekly audits and stewardship education was carried out among dentists in Ohio, USA. Adequate antibiotic use increased from 19% to 87.9% because of the strategy.[72] Patient-focused initiatives emphasize the importance of alternative pain management and inform patients about the dangers of self-medication. Digital health technologies (DHTs) offer scalable and adaptable ways to improve ASPs, especially through focused public, student, and clinician education initiatives.[73]

Policy development and advocacy: According to WHO guidelines, AMS programs must be included in national dental AMR action plans. Compared to medicine, dental treatment is currently frequently left out of surveillance programs. Global health policy must incorporate dental monitoring systems and push professional associations to create official standards to address these concerns.[74]

Integration of AMS into undergraduate and postgraduate dental curriculum: The Dentistry curriculum worldwide lacks protocols on AMS training. The subjects are not sufficiently covered, and there are no standardized procedures to put theoretical understanding into reality.[75] Various survey-based studies showed that students in dentistry are aware of this educational gap and try to refer to various websites to address their shortcomings.[76] A better prescribing culture will be achieved by incorporating prescribing activities, assessments, and modules.

Conclusion

AMS in dentistry is essential to combat rising AMR by promoting evidence-based prescribing, prioritizing local treatments, and restricting antibiotics to justified cases. Dentists can play a vital role in reducing resistance. Education, audits, decision-support tools, and collaborative care models have shown clear benefits. Strengthening AMS policies and ensuring consistent guideline adherence will safeguard antibiotics as effective treatments for generations to come.

References

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance. 2023. Antimicrobial resistance

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629-655. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- FDI World Dental Federation. Antibiotic Stewardship in Dentistry. 2019. Antibiotic Stewardship in Dentistry

- Gross AE, Hanna D, Rowan SA, Bleasdale SC, Suda KJ. Successful Implementation of an Antibiotic Stewardship Program in an Academic Dental Practice. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(3):ofz067. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofz067 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rachael England. Antibiotic stewardship in dentistry: Adopted by the General Assembly: September 2019, San Francisco, United States of America. Int Dent J. 2020;70(1):9-10. doi:10.1111/idj.12553 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kates OS. What Is Antimicrobial Stewardship?. AMA J Ethics. 2024;26(6):E437-E440. doi:10.1001/amajethics.2024.437 PubMed | Crossref

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship. 2025. Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship

- FDI World Dental Federation. Preventing AMR and Infections. Preventing AMR and Infections

- Cirkel LL, Herrmann JM, Ringel C, Wöstmann B, Kostev K. Antibiotic Prescription in Dentistry: Trends, Patient Demographics, and Drug Preferences in Germany. Antibiotics (Basel). 2025;14(7):676. doi:10.3390/antibiotics14070676 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rutherford SJ, Glenny AM, Roberts G, Hooper L, Worthington HV. Antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing bacterial endocarditis following dental procedures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;5(5):CD003813. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003813.pub5 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Salgado-Peralvo ÁO, Kewalramani N, Pérez-Jardón A, Pérez-Sayáns M, Mateos-Moreno MV, Arriba-Fuente L. Antibiotic prescribing patterns in the placement of dental implants in Europe: A systematic review of survey-based studies. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2024;29(3):e441-450. doi:10.4317/medoral.26450 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Suda KJ, Calip GS, Zhou J, et al. Assessment of the Appropriateness of Antibiotic Prescriptions for Infection Prophylaxis Before Dental Procedures, 2011 to 2015. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e193909. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3909 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Agnihotry A, Thompson W, Fedorowicz Z, van Zuuren EJ, Sprakel J. Antibiotic use for irreversible pulpitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;5(5):CD004969. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004969.pub5 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bhuvaraghan A, King R, Larvin H, Aggarwal VR. Antibiotic Use and Misuse in Dentistry in India-A Systematic Review. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021;10(12):1459. doi:10.3390/antibiotics10121459 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ahmed I, Rabbi M, Sultana S. Antibiotic resistance in Bangladesh: A systematic review. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;80:54-61. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2018.12.017 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bernatz JT, Safdar N, Hetzel S, Anderson PA. Antibiotic Overuse is a Major Risk Factor for Clostridium difficile Infection in Surgical Patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(10):1254-1257. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.158 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rajasekaran JJ, Krishnamurthy HK, Bosco J, et al. Oral Microbiome: A Review of Its Impact on Oral and Systemic Health. Microorganisms. 2024;12(9):1797. doi:10.3390/microorganisms12091797 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lockhart PB, Tampi MP, Abt E, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on antibiotic use for the urgent management of pulpal- and periapical-related dental pain and intraoral swelling: A report from the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc. 2019;150(11):906-921.e12. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2019.08.020 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Moretta A, Scieuzo C, Petrone AM, et al. Antimicrobial Peptides: A New Hope in Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Fields. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:668632. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2021.668632 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Guerrini L, Monaco A, Pietropaoli D, Ortu E, Giannoni M, Marci M. Antibiotics in dentistry: A narrative review of literature and guidelines considering antibiotic resistance. Open Dent J. 2019;13:383-398. doi:10.2174/1874210601913010383 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wilson WR, Gewitz M, Lockhart PB, et al. Prevention of Viridans Group Streptococcal Infective Endocarditis: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(20):e963-e978. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000969 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Goff DA, Mangino JE, Glassman AH, Goff D, Larsen P, Scheetz R. Review of Guidelines for Dental Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Prevention of Endocarditis and Prosthetic Joint Infections and Need for Dental Stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(2):455-462. doi:10.1093/cid/ciz1118 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- American Dental Association. Antibiotic Prophylaxis Prior to Dental Procedures. ADA Library & Archives, Oral Health Topics. 2022 Jan 5. Antibiotic Prophylaxis Prior to Dental Procedures

- Sollecito TP, Abt E, Lockhart PB, et al. The use of prophylactic antibiotics prior to dental procedures in patients with prosthetic joints: Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for dental practitioners–a report of the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146(1):11-16.e8. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2014.11.012 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Merlos A, Vinuesa T, Jané-Salas E, López-López J, Viñas M. Antimicrobial prophylaxis in dentistry. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2014;2(4):232-238. doi:10.1016/j.jgar.2014.05.007 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lockhart PB, Tampi MP, Abt E, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on antibiotic use for the urgent management of pulpal- and periapical-related dental pain and intraoral swelling: A report from the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc. 2019;150(11):906-921.e12. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2019.08.020 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Contaldo M, D’Ambrosio F, Ferraro GA, et al. Antibiotics in Dentistry: A Narrative Review of the Evidence beyond the Myth. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(11):6025. Published 2023 Jun 1. doi:10.3390/ijerph20116025 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kherul Anuwar AH, Saub R, Safii SH, et al. Systemic Antibiotics as an Adjunct to Subgingival Debridement: A Network Meta-Analysis. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022;11(12):1716. doi:10.3390/antibiotics11121716 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- De Waal YCM, Vangsted TE, Van Winkelhoff AJ. Systemic antibiotic therapy as an adjunct to non-surgical peri-implantitis treatment: A single-blind RCT. J Clin Periodontol. 2021;48(7):996-1006. doi:10.1111/jcpe.13464 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Menon RK, Gomez A, Brandt BW, et al. Long-term impact of oral surgery with or without amoxicillin on the oral microbiome-A prospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):18761. Published 2019 Dec 10. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-55056-3 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Prajapati A, Prajapati A, Sathaye S. Benefits of not Prescribing Prophylactic Antibiotics After Third Molar Surgery. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2016;15(2):217-220. doi:10.1007/s12663-015-0814-1 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Teoh L, Cheung MC, Dashper S, James R, McCullough MJ. Oral Antibiotic for Empirical Management of Acute Dentoalveolar Infections-A Systematic Review. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021;10(3):240. Published 2021 Feb 28. doi:10.3390/antibiotics10030240 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Murray CJL, Ikuta KS, Sharara F, et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629-655. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Böhmer F, Hornung A, Burmeister U, et al. Factors, Perceptions and Beliefs Associated with Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing in German Primary Dental Care: A Qualitative Study. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021;10(8):987. Published 2021 Aug 16. doi:10.3390/antibiotics10080987 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Roganović J, Djordjević S, Barać M, Crnjanski J, Milanović I, Ilić J. Dental Antimicrobial Stewardship: Developing a Mobile Application for Rational Antibiotic Prescribing to Tackle Misdiagnosis. Antibiotics (Basel). 2024;13(12):1135. Published 2024 Nov 26. doi:10.3390/antibiotics13121135 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Elouafkaoui P, Young L, Newlands R, et al. An Audit and Feedback Intervention for Reducing Antibiotic Prescribing in General Dental Practice: The RAPiD Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. PLoS Med. 2016;13(8):e1002115. Published 2016 Aug 30. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002115 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Chate RA, White S, Hale LR, et al. The impact of clinical audit on antibiotic prescribing in general dental practice. Br Dent J. 2006;201(10):635-641. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4814261 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mendez-Romero J, Rodríguez-Fernández A, Ferreira M, et al. Interventions to improve antibiotic use among dentists: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2025;80(6):1494-1507. doi:10.1093/jac/dkaf118 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Schneider-Smith EG, Suda KJ, Lew D, et al. How decisions are made: Antibiotic stewardship in dentistry. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2023;44(11):1731-1736. doi:10.1017/ice.2023.173 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors. Promoting Antibiotic Stewardship in Dentistry: Policy Statement. April 2020. Promoting Antibiotic Stewardship in Dentistry: Policy Statement

- Goff DA, Mangino JE, Trolli E, Scheetz R, Goff D. Private Practice Dentists Improve Antibiotic Use After Dental Antibiotic Stewardship Education From Infectious Diseases Experts. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(8):ofac361. Published 2022 Jul 25. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofac361 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Okihata R, Michi Y, Sunakawa M, Tagashira Y. Pharmacist-led multi-faceted intervention in an antimicrobial stewardship programme at a dental university hospital in Japan. J Hosp Infect. 2023;136:30-37. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2023.04.006 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Thabit AK, Aljereb NM, Khojah OM, Shanab H, Badahdah A. Towards Wiser Prescribing of Antibiotics in Dental Practice: What Pharmacists Want Dentists to Know. Dent J (Basel). 2024;12(11):345. Published 2024 Oct 29. doi:10.3390/dj12110345 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Chopra R, Merali R, Paolinelis G, Kwok J. An audit of antimicrobial prescribing in an acute dental care department. Prim Dent J. 2014;3(4):24-29. doi:10.1308/205016814813877270 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Johnson TM, Hawkes J. Awareness of antibiotic prescribing and resistance in primary dental care. Prim Dent J. 2014;3(4):44-47. doi:10.1308/205016814813877324 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Tomczyk S, Whitten T, Holzbauer SM, Lynfield R. Combating antibiotic resistance: a survey on the antibiotic-prescribing habits of dentists. Gen Dent. 2018;66(5):61-68. Combating antibiotic resistance: a survey on the antibiotic-prescribing habits of dentists

- Ramanathan S, Yan C, Suda KJ, et al. Barriers and facilitators to guideline concordant dental antibiotic prescribing in the United States: A qualitative study of the National Dental PBRN. J Public Health Dent. 2024;84(2):163-174. doi:10.1111/jphd.12611 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ashiru-Oredope D, Hopkins S; English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilization and Resistance Oversight Group. Antimicrobial stewardship: English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilization and Resistance (ESPAUR). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(11):2421-2423. doi:10.1093/jac/dkt363 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Alghamdi S, Atef-Shebl N, Aslanpour Z, Berrou I. Barriers to implementing antimicrobial stewardship programmes in three Saudi hospitals: Evidence from a qualitative study. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019;18:284-290. doi:10.1016/j.jgar.2019.01.031 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Khan M, Khan S, Basharat S. Gaps and Barriers to the Implementation of Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes in Hospitals of Pakistan. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2025;35(1):122-124. doi:10.29271/jcpsp.2025.01.122 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wu S, Tannous E, Haldane V, Ellen ME, Wei X. Barriers and facilitators of implementing interventions to improve appropriate antibiotic use in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review based on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement Sci. 2022;17(1):30. Published 2022 May 12. doi:10.1186/s13012-022-01209-4 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gunasekara YD, Kinnison T, Kottawatta SA, Kalupahana RS, Silva-Fletcher A. Exploring Barriers to One Health Antimicrobial Stewardship in Sri Lanka: A Qualitative Study among Healthcare Professionals. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022;11(7):968. Published 2022 Jul 19. doi:10.3390/antibiotics11070968 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Spittle LS, Muzzin KB, Campbell PR, DeWald JP, Rivera-Hidalgo F. Current prescribing Practices for Antibiotic Prophylaxis: A Survey of Dental Practitioners. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2017;18(7):559-566. Published 2017 Jul 1. doi:10.5005/jp-journals-10024-2084 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Shallcross LJ, Davies DS. Antibiotic overuse: a key driver of antimicrobial resistance. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(629):604-605. doi:10.3399/bjgp14X682561 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Telang LA, Nerali JT, Pishipati KV, Siddiqui FS, Telang A. Antimicrobial stewardship—implementation and improvements in antibiotic-prescribing practices in a dental school. Arch Med Health Sci. 2021;9(1):80-86. doi:10.4103/amhs.amhs_20_21 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Martínez-González NA, Keizer E, Plate A, et al. Point-of-Care C-Reactive Protein Testing to Reduce Antibiotic Prescribing for Respiratory Tract Infections in Primary Care: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020;9(9):610. Published 2020 Sep 16. doi:10.3390/antibiotics9090610 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Eley CV, Sharma A, Lee H, Charlett A, Owens R, McNulty CAM. Effects of primary care C-reactive protein point-of-care testing on antibiotic prescribing by general practice staff: pragmatic randomised controlled trial, England, 2016 and 2017. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(44):1900408. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.44.1900408 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gentile I, Schiano Moriello N, Hopstaken R, Llor C, Melbye H, Senn O. The Role of CRP POC Testing in the Fight against Antibiotic Overuse in European Primary Care: Recommendations from a European Expert Panel. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(2):320. Published 2023 Jan 15. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13020320 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lee SA, Brokowski T, Chiang JN. Enhancing antibiotic stewardship using a natural language approach for better feature representation. arXiv [preprint]. Posted May 30, 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2405.20419 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Dar-Odeh N, Babkair H, Alnazzawi A, Abu-Hammad S, Abu-Hammad A, Abu-Hammad O. Utilization of Teledentistry in Antimicrobial Prescribing and Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases during COVID-19 Lockdown. Eur J Dent. 2020;14(S 01):S20-S26. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1717159 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Harandi H, Shafaati M, Salehi M, et al. Artificial intelligence-driven approaches in antibiotic stewardship programs and optimizing prescription practices: A systematic review. Artif Intell Med. 2025;162:103089. doi:10.1016/j.artmed.2025.103089 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Garg AK, Agrawal N, Tewari RK, Kumar A, Chandra A. Antibiotic prescription pattern among Indian oral healthcare providers: a cross-sectional survey. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(2):526-528. doi:10.1093/jac/dkt351 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- American Dental Association. Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline on Antibiotic Use for the Urgent Management of Pulpal- and Periapical-Related Dental Pain and Intraoral Swelling: A Report from the American Dental Association. 2019. Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline on Antibiotic Use for the Urgent Management of Pulpal- a…

- Huynh CT, Gouin KA, Hicks LA, Kabbani S, Neuburger M, McDonald E. Outpatient antibiotic prescribing by general dentists in the United States from 2018 through 2022. J Am Dent Assoc. 2025;156(5):382-389.e2. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2024.12.003 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Teoh L, Thompson W, Suda K. Antimicrobial stewardship in dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2020;151(8):589-595. doi:10.1016/j.esmoop.2020.04.023 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Graells T, Lambraki I, Cousins M, et al. Exploring the factors that contribute to the successful implementation of antimicrobial resistance interventions: a comparison of high‑income and low‑middle‑income countries. Front Public Health. 2023;11. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1230848 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cooper D, Stevens C, Jamieson C, et al. Implementation of a National Antimicrobial Stewardship Training Programme for General Practice: A Case Study. Antibiotics (Basel). 2025;14(2):148. Published 2025 Feb 3. doi:10.3390/antibiotics14020148 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Seneviratne CJ, Leung KC, Wong CH, et al. Nanoparticle-encapsulated chlorhexidine against oral bacterial biofilms. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103234. Published 2014 Aug 29. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103234 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Yin IX, Udduttulla A, Xu VW, Chen KJ, Zhang MY, Chu CH. Use of Antimicrobial Nanoparticles for the Management of Dental Diseases. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2025;15(3):209. Published 2025 Jan 28. doi:10.3390/nano15030209 PubMed |Crossref | Google Scholar

- Zhu M, Hao C, Zou T, Jiang S, Wu B. Phage therapy as an alternative strategy for oral bacterial infections: a systematic review. BMC Oral Health. 2025;25(1):44. Published 2025 Jan 8. doi:10.1186/s12903-024-05399-9 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Xu J, Zhou X, Gao Z, Song YY, Schmuki P. Visible-Light-Triggered Drug Release from TiO2 Nanotube Arrays: A Controllable Antibacterial Platform. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55(2):593-597. doi:10.1002/anie.201508710 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mahmood A, Tabassum H, Hussain S, Ghauri M Q K, Baloch F, Sultan J. Dentists’ knowledge regarding antibiotic prescription, and dosage of the prescribed antibiotics. Pak J Med Health Sci. 2022;16:566‑568. doi:10.53350/pjmhs221610566 Crossref

- Monaci M, Rake A, Acampora M, Barello S. Digital educational interventions for antimicrobial stewardship: A systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2025;21(12):991-1012. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2025.07.003 PubMed |Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ticku S, Barrow J, Fuccillo R, McDonough JE. Oral Health Stakeholders: A Time for Alignment and Action. Milbank Q. 2021;99(4):882-903. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12525 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Martine C, Sutherland S, Born K, Thompson W, Teoh L, Singhal S. Dental antimicrobial stewardship: a qualitative study of perspectives among Canadian dentistry sector leaders and experts in antimicrobial stewardship. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2024;6(3):dlae082. Published 2024 May 22. doi:10.1093/jacamr/dlae082 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bajalan A, Bui T, Salvadori G, et al. Awareness regarding antimicrobial resistance and confidence to prescribe antibiotics in dentistry: a cross-continental student survey. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2022;11(1):158. Published 2022 Dec 11. doi:10.1186/s13756-022-01192-x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

The authors declare that there are no acknowledgments to disclose.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the publication of this review article.

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Uswa Mansoor

Department of Pharmacy

Quaid-I-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan

Email: uswamansoorwork@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Maida Noor, Muhammad Bilal Samra

Department of Pharmacy

Quaid-I-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan

Amna Farhat

Department of Dentistry

Bahria University of Health Sciences, Karachi, Pakistan

Samar Fatima, Momal Badar

Department of Pharmacy

The University of Faisalabad, Faisalabad, Pakistan

Pir Asif Ali

Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Medical University, Islamabad, Pakistan

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception, design, literature review, and writing of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable. This article is a review article and does not involve human or animal subjects.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Guarantor

Uswa Mansoor is the guarantor of the article and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole.

DOI

Cite this Article

Noor M, Mansoor U, Farhat A, et al. The Role of Antimicrobial Stewardship in Dentistry: Current Landscape and Prospects for the Future. medtigo J Pharmacol. 2025;2(4):e3061243. doi:10.63096/medtigo3061243 Crossref