Author Affiliations

Abstract

As we recover from the effects of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, the medical community globally is seeing the emergence of another challenge, which is the neuropsychiatric consequences of patients with long COVID. As COVID-19 recovered patients battle the challenges of emotional, persistent cognitive, and autoimmune symptoms such as fatigue, depression, brain fog, anxiety, and sleep disturbances, which are now potentially being recognized as part of a more complex multisystem disorder, it is crucial to pay attention to new developments that this novel coronavirus is causing. The growing evidence clearly highlights biological mechanisms such as microvascular injury, neuroinflammation, neurotransmitter disruption, and immune dysregulation. Still, there are systemic issues such as the absence of properly defined clinical frameworks, a lack of diagnostic tests, and healthcare systems that lack interdisciplinary coordination and collaboration, which have left many patients either underdiagnosed or without support. Our perspective paper calls attention to the urgent need for integrated care models, emphasizing the role nursing can play in symptom management and early recognition of any new symptoms in patients. We also focus on a reimagined approach to treating such patients by improving the collaboration between healthcare specialists in neurology and psychiatry. We believe that without such a coordinated effort in responding to the threat of long COVID, there will be a silent wave of chronic disability in the future.

Keywords

Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome, Neuropsychiatric disorders, Etiology; Cognitive dysfunction, Neuroinflammation, Nursing care, Health services accessibility.

Introduction

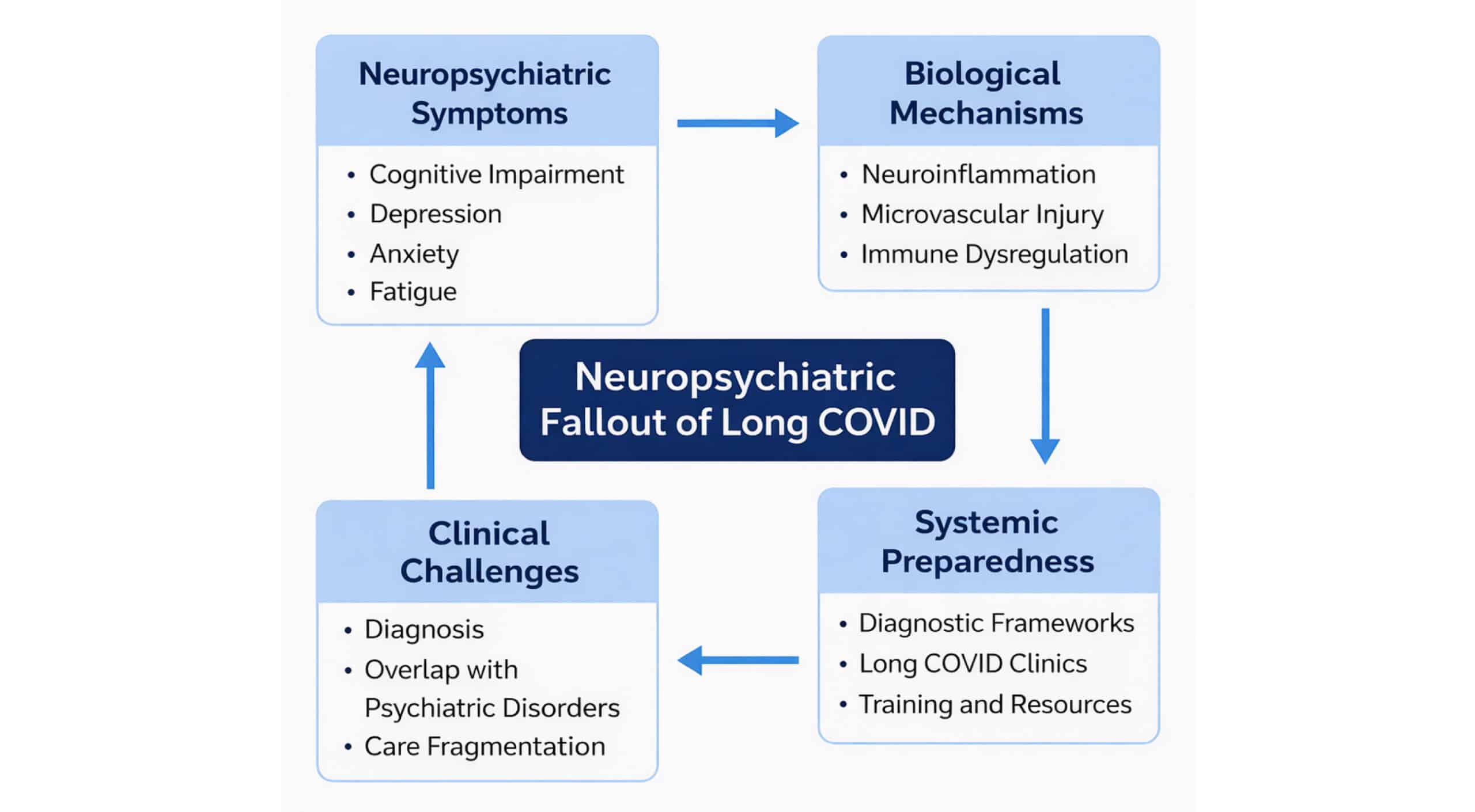

Since the first reported case of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in Wuhan in December 2019, which caused COVID-19, the world has seen multiple variants of the virus.[1] Researchers and scientists have been able to develop multiple strategies, including vaccine development, nanomedicine development, and novel therapeutics, including the use of artificial intelligence to fight the pandemic that caused mayhem in the normal day-to-day lives of individuals globally.[2,3] Today, almost five years since that first case, as the acute threat of the pandemic takes a back seat from making global headlines, another silent epidemic is rising to the surface: the long-term neuropsychiatric consequences of COVID-19 infection. This has been labelled as long COVID by experts due to the enduring and long-lasting nature of symptoms of the initial infection.[4-6] Many of these symptoms are cognitive or psychiatric and have emerged as a significant neurological public health burden. A graphical representation of the neuropsychiatric issues related to long COVID is shown in Figure 1. The clinical infrastructure, diagnostic methods, and public planning have been facing shortcomings and appear unprepared for this emerging challenge. The question that needs to be evaluated and answered is whether we are ready for the next wave, not the infection, but one of chronic disability.

Figure 1: Illustrative representation of the neuropsychiatric fallout of long COVID

The scope of the problem: Recent data from the World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that for every 100 patients who had COVID-19, about six develop long COVID.[7] Data from 2022 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that almost 6.9% of adults in the United States of America (USA) developed long COVID.[8] Another study estimates that about 400 million people are suffering from long COVID globally cumulatively.[9] Researchers have demonstrated that almost one in three people who are affected by COVID-19 develop or experience neuropsychiatric symptoms, which include brain fog, fatigue, memory loss, anxiety, depression, and psychosis.[10,11] The study by Taquet et al. in 2022 showed that the risk of psychotic disorders, seizures, and cognitive deficits was elevated when compared to that of influenza, thus proving the unique neurotropism of SARS-CoV-2.[11] Their study also highlighted that out of the 1.2 million patients included in the study, most patients were of a working-age population, indicating the significant impact of long COVID on the workforce, economy, and quality of life.[11] This is going to put additional strain on the global economic burden caused by neurological diseases.[9,12] Through this paper, the authors aim to highlight the biological, clinical, nursing, and systemic challenges and recommend readiness strategies in overcoming the dangers of long COVID.

Methodology

For this perspective article, a targeted review of literature between January 2020 and July 2025 was conducted. Databases in the search included PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Scopus, PsycINFO using keyword combinations “long COVID,” “post-COVID condition,” “neuropsychiatric,” “cognitive impairment,” “neuroinflammation,” “nursing care,” “health systems,” and “preparedness.” We focused on prioritizing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, large cohort studies, and papers related to policy matters that reported on cognitive or neuropsychiatric outcomes of long COVID. Further in the process, additional sources were identified by manually screening the reference lists of selected articles. Global organizations such as the WHO and the CDC were scanned for more information. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) peer-reviewed research papers published in English between January 2020 and November 2025, (b) reporting cognitive, neuropsychiatric, or psychological sequelae of long COVID, (c) articles that addressed nursing implications on healthcare systems, and (d) articles focusing on adult or mixed populations. Seminal or legacy papers were also included as necessary. Based on our findings, we organized this perspective article into four distinct domains as follows:

- Biological mechanisms

- Clinical challenges

- Nursing perspectives

- Systemic preparedness

1. Biological mechanisms of neuropsychiatric issues in long COVID :

The neuropsychiatric symptoms of long COVID have a distinct correlation with other underlying biological mechanisms. Research has proven the processes of neuroinflammation, microvascular endothelial injury, autoimmunity, dysautonomia, and neurotransmitter disruption.[13-19] Contemporary evidence points to additional layers of complexity in the disease process. Mitochondrial impairment has been shown to play a vital role in contributing to the many neurological symptoms, such as fatigue, vascular issues, or cognitive disturbances, associated with long COVID.[20] The study by Szögi et al.[21] focused on identifying novel biomarkers and found reduced levels of circulating cell-free mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid (ccf-mtDNA) in patients with long COVID. They proved the crucial role of long-term mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of long COVID. Epigenetic modifications, such as altered DNA methylation patterns due to pulmonary viruses such as SARS-CoV-2, can create a long memory of infection within immune and neural cells, thereby aiding in sustaining vulnerability even after viral load clearance.[22-24] Studies have highlighted a critical aspect linking SARS-CoV-2 in accelerating the pathways of neurodegeneration, such as enhanced tau phosphorylation and α-synuclein aggregation, thus raising concerns for long-term dementia, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s dementia.[25-29]

These findings highlight the multifactoral and systemic nature of long COVID. An all-inclusive framework linking immune dysregulation, vascular injury, viral persistence, and cellular dysfunction is needed to explain the wide-ranging neuropsychiatric presentation and to create pathways for future therapeutic targets. In Table 1, we list some of the biological mechanisms and the systemic correlations in long COVID.

| Mechanism | Description | Symptom correlates | References |

| Neuroinflammation | Cytokine storm and microglial activation contribute to widespread neuroinflammation and alteration in neuronal signaling. | Fatigue, brain fog, depression, cognitive slowing | 13 |

| Microvascular endothelial injury | Damage to endothelial cells may disrupt the blood–brain barrier, impairing central nervous system function, including oxygen and nutrient delivery. | Cognitive decline, headaches, strokes, microhemorrhages | 14 |

| Autoimmunity | Persistent viral fragments may trigger autoantibody production and immune dysregulation. | Mood disorders, chronic fatigue, and neuropsychiatric flare-ups | 15 |

| Dysautonomia | SARS-CoV-2 affects autonomic regulation, altering cardiovascular and respiratory function. | Postural tachycardia (POTS), sleep disturbance, and brain fog | 16,17 |

| Neurotransmitter disruption | Elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines interfere with neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate pathways. | Anxiety, depression, psychosis, anhedonia | 18,19 |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | Viral persistence and oxidative stress impair mitochondrial energy metabolism in neurons. | Cognitive fatigue, memory lapses, and reduced processing speed | 20,21 |

| Epigenetic modifications | Viral infection and inflammation induce DNA methylation and histone modifications, reprogramming gene expression. | Long-term susceptibility to depression, impaired synaptic plasticity, and cognitive rigidity | 22,23 |

| Viral persistence / Latency | Residual viral proteins and RNA may persist in the CNS or periphery, triggering chronic immune activation. | Ongoing fatigue, “relapsing-remitting” brain fog | 22-24 |

| Neurodegenerative pathway activation | SARS-CoV-2 proteins accelerate misfolding/ aggregation of tau and α-synuclein. | Parkinsonism, early cognitive impairment, memory decline | 25-29 |

Table 1: Biological mechanisms and symptom correlates in long COVID

2. Clinical challenges in diagnosis and management:

Coming to an accurate diagnosis and developing a practical management of the neuropsychiatric sequelae in long COVID presents us with complex and persistent challenges. These challenges point to the long-standing gaps in the manner in which psychiatric and cognitive symptoms are studied, coded, and treated in different healthcare systems globally. We present three key issues that, from our perspective, stand out.

- Symptom overlap with psychiatric and neurological disorders: Patients who have long COVID often present with cognitive symptoms such as poor concentration (brain fog), lapses in memory, along with fatigue, anxiety, or depression. These symptoms have a considerable overlap with primary psychiatric disorders (for example, major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder) and with neurologic syndromes (for example, mild cognitive impairment or post-concussive syndrome).[30] This can be challenging as it burdens the healthcare team and complicates diagnosis, thereby leading to errors by clinicians who can misdiagnose and attribute cognitive dysfunction to stress or burnout or psychiatric comorbidity instead of recognizing it as a potential neuropsychiatric manifestation of long COVID. Such misdiagnosis can delay correct therapeutic interventions.

- Lack of validated tools: Currently, the standardized diagnostic frameworks for cognitive and neuropsychiatric conditions post-COVID are in their infancy. Even though we have instruments such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), mini-mental state examination (MMSE), and NEUROSCREEN, which have been proposed and applied in research and clinical use, we do not have a validated consensus tool that is tailored towards neuropsychiatric assessment in long COVID or there os inconsistency in the application of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnostic codes.[31-35] This lack of synchronization and coordination in clinical practice often leads to limitations in cross-study comparability, which further weakens decision-making in the clinical setting.

- Under-recognition and stigma in patient encounters: Many patients have concerns that, due to various factors such as excessive workload on the clinicians, their cognitive or psychiatric complaints may go unnoticed or completely ignored by the clinicians as being transient or psychosomatic. Often, patients may appear high-functioning in the short clinical interactions but are struggling in real-world scenarios, including at work, caregiving, or multitasking.[36] Such a perception of under-recognition and illegitimacy tends to fuel stigma, thus discouraging patients from seeking the care they need and eroding overall trust in the healthcare system. Nurses can play an important role in helping overcome this stigma, as they often spend more time with patients and can validate and document these symptoms, thereby underscoring the importance of multidisciplinary care teams.

Studies have been documenting the severity, prevalence, and persistence of neurological and psychiatric sequelae in patients with COVID-19 infection. These include patient-led surveys, large-scale retrospective cohort studies using electronic health records (EHR), systematic reviews, and meta-analyses from 2021 to 2025, as seen in Table 2. Altogether, these studies highlight and reinforce the nature of clinical challenge in front of us and provide an evidence base to develop standardized diagnostic and management protocols.

| Author (Year) | Country / Setting | Design and sample | Neuropsychiatric outcomes | Key findings |

| Taquet et al.[37] (2021) | Multinational EHR network | Retrospective cohort of COVID-19 survivors; n=236,379 | Anxiety, mood disorders, insomnia, cognitive deficit, stroke, dementia | Substantial 6-month neuro/psychiatric morbidity vs other infections; risks are higher with severe COVID-19. |

| Hampshire et al.[38] (2021) | UK online cohort | Cross-sectional/observational; n=81,337 | Cognitive deficits (attention, planning, reasoning) | Significant global cognitive deficit vs controls; larger after hospitalization but present in community cases. |

| Davis et al.[39] (2021) | Global online survey | Longitudinal survey; n=3762 | Fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, PEM | After month 6, cognitive dysfunction is among the top symptoms; slow recovery trajectories, nursing-centered, patient-experience arguments. |

| Ahmed et al.[40] (2021) | Egypt | Observational; long-term; n=182 | Sleep, depression, anxiety | Long-term sleep & mood disturbances are common after COVID-19. |

| Riedel et al.[41] (2021) | Global

|

Nurses cohort

|

Anxiety, depression, burnout

|

Nurses reported significant mental health challenges post-COVID |

| Xu et al.[10] (2022)

|

USA Veterans Health | Cohort; n=154,068 COVID-19 vs controls | Memory problems, mental health disorders, stroke, seizures, and movement disorders | Increased 12-month risk across neurologic disorders; elevated even in non-hospitalized patients. |

| Taquet et al.[11] (2022) | Multinational EHR network | Retrospective cohort; n=1,284,437 | Anxiety/mood, psychosis, seizures, dementia, cognitive deficit | Anxiety/mood risks are transient, but psychosis, seizures, dementia, and cognitive deficits persist up to 2 years. |

| Premraj et al.[13] (2022) | Global | Systematic review/ meta-analysis (18 studies; patients n=10,530) | Fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, sleep, depression, anxiety | Fatigue=37%,

Brain fog=32%, Memory issues=22% Sleep disturbance=31%; Anxiety=23% Depression=17% |

| Hampshire et al.[42] (2022) | UK post-ICU | Observational; post-severe COVID; n=46 | Cognitive profile and recovery | Deficits relate to acute severity and recover slowly if at all; a multivariate profile is described. |

| Badenoch et al.[43] (2022) | Global | Systematic review/meta-analysis (51 studies; patients n=18,917) | Insomnia, fatigue, cognitive impairment, anxiety | Neuropsychiatric symptoms are common and persistent up to 6 months; notable sleep disturbances and fatigue. |

| Crivelli et al.[44] (2022) | Global | Systematic review (+meta-analysis subset); (27 studies; patients n=2049) | General cognition (MoCA), executive function, attention, and memory | COVID-recovered patients show lower general cognition vs controls up to 7 months. |

| Zeng et al.[18] (2023) | Global | Systematic review/meta-analysis (151 studies; patients n=1,285,407) | Long-term physical and mental sequelae | About 50% of survivors have persistent physical/psychiatric sequelae up to ≥12 months. |

| Ley et al.[45] (2023) | Multicenter/registry analyses | Retrospective cohort / EHR registry | Neurologic/psychiatric outcomes up to 2 years | EHR-based evidence that hospitalised patients have a higher long-term risk for seizures/epilepsy and other neurologic outcomes. |

| Taquet et al.[46] (2024) | United Kingdom | Prospective longitudinal cohort (hospitalized COVID-19 survivors); n=475 | Cognitive and psychiatric symptom trajectories, work outcomes | 2-3-year follow-up showing persistent cognitive/psychiatric symptoms after severe illness with measurable impact on employment and daily functioning. |

| Hampshire et al.[47] (2024) | Multi-country online cohort | Observational; n= 112,964 | Memory, executive function | Measurable cognitive deficits scale with illness severity and persist over time. |

| Jaywant et al.[36] (2024) | USA | Survey study; community adults; n=14,767 | Self-reported brain fog, memory/attention, functioning, employment, depression | Cognitive symptoms are common and tied to functional impairment and lower employment probability. |

| Seighali et al.[48] (2024) | Global | Systematic review/meta-analysis (165 studies) | Depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders in PCS | Substantial global burden of depression/anxiety/sleep disturbance in post-COVID syndrome. |

| Meca-García et al.[49] (2024) | Spain | Retrospective-prospective cohort mixed observational study; 2-year follow-up after severe COVID-19; n=201 | Depression, anxiety, PTSD, cognitive | Clinical/biological/social factors linked to persistent neuropsychiatric symptoms at 2 years. |

| Chau et al.[50] (2024) | Hong Kong | Cross-sectional / case-control study; n=223 post COVID and n=224 non COVID | Symptom phenotypes, persistent neuropsychiatric clusters | Defined phenotypes of chronic neuropsychiatric symptom clusters and linked them to quality-of-life measures. |

| Yasir et al.[51] (2024) | Cuba | Prospective follow-up study; n=178 | Psychosis, cognitive decline | COVID-19 patients with comorbidities have a high risk of getting severe COVID symptoms and long-term post-COVID neuropsychiatric issues. |

| Elboraay et al.[52] (2025) | Global | Systematic review/meta-analysis (125 studies) | Fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, mood disorders | Substantial prevalence of long-term neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with COVID-19 patients. |

| Panagea et al.[53] (2025) | Global | Systematic review (36 studies) | Executive function, memory, and attention deficits | High rate of recurrence of cognitive impairment post-COVID-19 infection. |

| Araújo et al.[54] (2025) | Portugal | Prospective cohort; 2-year follow-up; n=698 | Cognitive impairment post-mild to severe infection | Measurable cognitive deficits up to 2 years post-infection and linkage of deficits to severity & vaccination status. |

Table 2: Key studies highlighting the clinical challenges of long COVID

3. Nursing perspective:

- The frontline role: Nurses are the backbone of clinics and hospitals and are often the first point of contact and those who interact the most with the patients. So, from the nursing perspective, long COVID symptoms can present a multidimensional care challenge that can extend beyond clinical symptom management. As nurses spend a lot of their duty time in patient care, they are well-trained to identify any subtle changes in the patient’s symptoms, whether cognitive or emotional, that can sometimes go unnoticed in a brief physician-patient encounter. Nurses can play a crucial role in advocating for more rigorous neuropsychiatric assessment and pushing for guiding interdisciplinary care pathways.

- Early recognition and monitoring of subtle symptoms: Nurses play a critical role in detecting early signs and symptoms that can be overlooked, such as brain fog, irritability, short-term memory lapses, or sleep disturbances in long COVID patients. Routine conversations and repeated observations during hospital stays, or follow-ups in outpatient clinic visits, have put nurses in a unique situation to spot subtle behavioural or cognitive changes that may go under-reported by patients. Such vigilance provides early recognition and assists in creating opportunities for timely referrals to psychiatry or neurology-related services.

- Holistic interventions in everyday care: Nurses are uniquely positioned to implement more holistic interventions in low-resource settings, such as pacing strategies, nursing care plans, maintaining symptom diaries, and providing supportive education, thereby drastically improving patient agency and reducing psychological burden. A recent study noted that in dementia care in the post-pandemic era, nurses can play a key role in tracking neuropsychiatric symptoms and help maintain therapeutic consistency, which can, in turn, be applied to the broader population of patients with long COVID.[55]

- Gaps in training and the need for standardized frameworks: The absence of formal nursing frameworks for dealing with the challenges of long COVID can hinder the provision of a standardized nursing care delivery model. Despite their frontline position, nurses have reported feeling undertrained to manage post-COVID psychiatric or cognitive symptoms.[41,56]. Without well-established and clear protocols, the current approaches to assessment and management of such patients remain inconsistent, which in turn leads to variability in quality of care locally and globally. The need for developing evidence-based guidelines and integrating nurse specialists in long COVID clinics, both in resource-rich and low-resource settings, is all the more essential today.

4. Systemic preparedness:

As we are seeing improvement in recognition of long COVID as being clinically relevant, there is an insufficiency being noticed in overall systemic preparedness. The current fragmented nature of healthcare delivery, gaps in interdisciplinary collaboration, and shortages in workforce readiness tend to limit health systems in responding efficiently. Select key issues as described below help illustrate the challenges:

- Patchy access to long COVID clinics: Many tertiary hospitals or academic institutions in developed countries have launched long COVID clinics.[57-60] Even with this development, access can be inconsistent, especially in low-resource or rural areas. Patients can end up with long wait times for appointments, broken referral pathways, and ever-increasing financial burdens.[61-63] Data from the USA and European Union (EU) countries suggest that patients can frequently go undiagnosed or receive inadequate treatment due to the lack of standardization in the referral system or uneven geographic distribution of services.[64]

- Lack of integration between psychiatry and neurology: The separation of clinical specialities, especially neurology and psychiatry, in traditional healthcare often leads to issues related to the care of patients with long COVID.[65] Cognitive symptoms fall under neurology, but psychiatric specialists manage associated depression or anxiety, and there is often minimal coordination between these two specialties. This, in turn, can delay diagnosis, cause duplication of services, and cause economic burden on patients. Researchers have emphasized integrating neuropsychiatric approaches and acknowledged the biological and psychosocial overlap in patients with long COVID.[9,66]

- Workforce training deficiencies: Healthcare professionals, including physicians, nurses, and allied health workers, have reported limited training and a lack of confidence in managing patients with long COVID symptoms. Insufficient continuing education, lack of standardized clinical guidelines, and the general stigma associated with post-viral syndromes drastically increase these deficiencies. Surveys have shown that there is an urgent need for workforce-wide educational initiatives to overcome under-preparedness in identifying emotional and cognitive symptoms.[41,56]

- Policy-level changes and multidisciplinary unit models: The emergence of long COVID highlights the need for changes at the policy level to have an effective change at the care level by incorporating integration of different disciplines, including neurology, psychiatry, cardiology, pulmonology, rehabilitation, and nursing expertise into a single multidisciplinary unit of care. Select long COVID centers in the USA and the UK have successfully demonstrated the potential such an integrated care system has on improved patient outcomes.[64,66] International policy initiatives from global organizations such as the WHO and the CDC call for an increase in investments in long COVID research, standardization of diagnostic frameworks, and simplifying reimbursements, all while better understanding the complexity of post-COVID care of patients.[7,8]

The Way Forward: Integrating Mind and Brain

With growing evidence on the interlinkage of COVID and neuropsychiatric symptoms, we must move towards an integrated structure of diagnosis, treatment, research, and healthcare policy. To address this, we need to first acknowledge that the brain and mind function together, shaped by immunological, viral, and psychosocial factors, and we need to bridge the traditional divide between neurology and psychiatry. Below are five strategies that can prove essential to address this moving forward:

Standardized diagnostic frameworks: The most crucial step for advancing care is the development of a standardized diagnostic framework. Current instruments, such as the MoCA and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), are not validated specifically for long COVID neuropsychiatric sequelae.[67] Patients have to deal with inconsistent assessments, and cross-study comparability is limited due to a lack of harmonized criteria. It is important to add new ICD-11 categories of cognitive and psychiatric symptoms to emerging post-COVID conditions, as has been advised by the WHO.[7,9]. Incorporation of neurocognitive screening should be added as a standard diagnostic protocol.[34]

Multidisciplinary clinics: Multidisciplinary clinics play an important role in healthcare. Improved patient outcomes, especially in post-COVID care, have been noted by the integration of different disciplines such as neurology, psychiatry, pulmonology, cardiology, rehabilitation, and nursing.[64,66] Such setups streamline referral and provide continuity of care while validating patient experience.

Longitudinal biomarker studies: Research in the near future should focus on biomarkers and the natural evolution of the coronavirus to understand the underlying biological aspects of long COVID.[68] Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), neurofilament light chain (NfL), inflammatory cytokines, and other neuroimaging biomarkers are currently being studied for their diagnostic and prognostic potential in patients with long COVID neurological and psychiatric symptoms.[69,70,71] By distinguishing post-COVID cognitive impairment from non-COVID psychiatric illness with biomarker-driven pathways, we can develop targeted therapeutics and group patients for clinical trials.

Public awareness and destigmatization: The need of the hour is for the destigmatization of psychiatric symptoms of long COVID to improve patient outcomes. The focus in public health campaigns at the grassroots should be to educate that the neuropsychiatric sequelae are biological and not psychosomatic.[72,73] Awareness drives help reduce barriers to care and encourage patients to seek timely help. Timely incorporation of inputs from patient advocacy groups in policy and clinical guidelines will help ensure the interventions reflect real-world needs.[8,74]

Role of artificial intelligence and digital tools in rehabilitation: Digital health tools and artificial intelligence (AI) have shown promise in assessment and rehabilitation. AI-driven cognitive screening applications, wearable remotely monitored devices, and integration of machine learning models in the detection of relapses will transform the delivery of care and patient outcomes.[75-77]

Conclusion

In the post-COVID pandemic era, the emergence of long COVID is redefining the challenges in healthcare. There is an urgency of preparedness that cannot be overlooked. Globally, a new wave of chronic and disabling conditions is threatening us if decisive actions are not taken now. Systematic screening, early recognition, and proactive monitoring have to be actively scaled at primary and specialty care settings. We have to face this head-on collaboratively. As doctors and nurses play a critical role on the frontline, more research into biomarker discovery and novel therapeutic trials is needed. Policy has to be renewed so that patients are not left to go from door to door in search of quality care. The use of emerging technological tools in AI should be used to better assist in addressing the issues to safeguard global neurological and mental health and prepare us for the next public health crisis.

References

- Yamamoto V, Bolanos JF, Fiallos J, et al. COVID-19: review of a 21st century pandemic from etiology to neuro-psychiatric implications. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;77(2):459-504. doi:10.3233/JAD-200831

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Varahachalam SP, Lahooti B, Chamaneh M, et al. Nanomedicine for the SARS-CoV-2: state-of-the-art and future prospects. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021;16:539-560. doi:10.2147/IJN.S283686

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Gage A, Brunson K, Morris K, et al. Perspectives of manipulative and high-performance nanosystems to manage consequences of emerging new severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 variants. Front Nanotechnol. 2021;3:700888. doi:10.3389/fnano.2021.700888

Crossref | Google Scholar - Raveendran AV, Jayadevan R, Sashidharan S. Long COVID: an overview. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021;15(3):869-875. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2021.04.007

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, Topol EJ. Author correction: Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21(6):408. doi:10.1038/s41579-023-00896-0

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Altmann DM, Whettlock EM, Liu S, Arachchillage DJ, Boyton RJ. The immunology of long COVID. Nat Rev Immunol. 2023;23(10):618-634. doi:10.1038/s41577-023-00904-7

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - World Health Organization. Post COVID-19 condition (long COVID). Published February 26, 2025. Accessed July 24, 2025.

Post COVID-19 condition (long COVID) - Adjaye-Gbewonyo D, Vahratian A, Perrine CG, Bertolli J. Products data briefs number 480 September 2023. National Center for Health Statistics. doi:10.15620/cdc:132417

Crossref | Google Scholar - Al-Aly Z, Davis H, McCorkell L, et al. Long COVID science, research and policy. Nat Med. 2024;30(8):2148-2164. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03173-6

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Xu E, Xie Y, Al-Aly Z. Long-term neurologic outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2022;28(11):2406-2415. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-02001-z

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Taquet M, Sillett R, Zhu L, et al. Neurological and psychiatric risk trajectories after SARS-CoV-2 infection: an analysis of 2-year retrospective cohort studies including 1,284,437 patients. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(10):815-827. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00260-7

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Morris K, Nami M, Bolanos JF, et al. Neuroscience20 (BRAIN20, SPINE20, and MENTAL20) health initiative: a global consortium addressing the human and economic burden of brain, spine, and mental disorders through neurotech innovations and policies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;83(4):1563-1601. doi:10.3233/JAD-215190

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Premraj L, Kannapadi NV, Briggs J, et al. Mid and long-term neurological and neuropsychiatric manifestations of post-COVID-19 syndrome: a meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2022;434:120162. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2022.120162

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Lee MH, Perl DP, Nair G, et al. Microvascular injury in the brains of patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2033369

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Sher EK, Ćosović A, Džidić-Krivić A, Farhat EK, Pinjić E, Sher F. COVID-19 a triggering factor of autoimmune and multi-inflammatory diseases. Life Sci. 2023;319:121531. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121531

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Larsen NW, Stiles LE, Shaik R, et al. Characterization of autonomic symptom burden in long COVID: a global survey of 2,314 adults. Front Neurol. 2022;13:1012668. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.1012668

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Carmona-Torre F, Mínguez-Olaondo A, López-Bravo A, et al. Dysautonomia in COVID-19 patients: a narrative review on clinical course, diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Front Neurol. 2022;13:886609. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.886609

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Zeng N, Zhao YM, Yan W, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of long term physical and mental sequelae of COVID-19 pandemic: call for research priority and action. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28(1):423-433. doi:10.1038/s41380-022-01614-7

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Lai YJ, Liu SH, Manachevakul S, Lee TA, Kuo CT, Bello D. Biomarkers in long COVID-19: a systematic review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1085988. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1085988

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Molnar T, Lehoczki A, Fekete M, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in long COVID: mechanisms, consequences, and potential therapeutic approaches. Geroscience. 2024;46(5):5267-5286. doi:10.1007/s11357-024-01165-5

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Szögi T, Borsos BN, Masic D, et al. Novel biomarkers of mitochondrial dysfunction in Long COVID patients. GeroScience. 2025;47:2245-2261. doi:10.1007/s11357-024-01398-4

Crossref | Google Scholar - Griffin DE. Why does viral RNA sometimes persist after recovery from acute infections?. PLoS Biol. 2022;20(6):e3001687. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3001687

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Wrede D, Bordak M, Abraham Y, Mehedi M. Pulmonary Pathogen-Induced Epigenetic Modifications. Epigenomes. 2023;7(3):13. doi:10.3390/epigenomes7030013

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Chen B, Julg B, Mohandas S, Bradfute SB; RECOVER Mechanistic Pathways Task Force. Viral persistence, reactivation, and mechanisms of long COVID. Elife. 2023;12:e86015. doi:10.7554/eLife.86015

PubMed |Crossref | Google Scholar - Green R, Mayilsamy K, McGill AR, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection increases the gene expression profile for Alzheimer’s disease risk. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2022;27:217-229. doi:10.1016/j.omtm.2022.09.007

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Semerdzhiev SA, Fakhree MAA, Segers-Nolten I, Blum C, Claessens MMAE. Interactions between SARS-CoV-2 N-Protein and α-Synuclein Accelerate Amyloid Formation. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2022;13(1):143-150. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.1c00666

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Zhao J, Xia F, Jiao X, Lyu X. Long COVID and its association with neurodegenerative diseases: pathogenesis, neuroimaging, and treatment. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1367974. doi:10.3389/fneur.2024.1367974

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Lee HK, Choi JY, Park JH, Chang MH, Park JH, Koh YH. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein causes synaptic dysfunction and p-tau and α-synuclein aggregation leading to cognitive impairment: the protective role of metformin. PLoS One. 2025;20(11):e0336015. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0336015

Crossref | Google Scholar - Elechi KW, Oyepeju Nkem O, Timothy Chibueze N, Elechi US, Franklin Chimaobi K. Long-term Neurological Consequences of COVID-19 in Patients With Pre-existing Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Neurosci Insights. 2025;20:26331055251342755. doi:10.1177/26331055251342755

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - De Luca R, Bonanno M, Calabrò RS. Psychological and cognitive effects of long COVID: a narrative review focusing on the assessment and rehabilitative approach. J Clin Med. 2022;11(21):6554. doi:10.3390/jcm11216554

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Ellis RJ, Evans SR, Clifford DB, et al. Clinical validation of the NeuroScreen. J Neurovirol. 2005;11(6):503-511. doi:10.1080/13550280500384966

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Nami M, Thatcher R, Kashou N, et al. A proposed brain-, spine-, and mental-health screening methodology (NEUROSCREEN) for healthcare systems: position of the Society for Brain Mapping and Therapeutics. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;86(1):21-42. doi:10.3233/JAD-215240

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Pfaff ER, Madlock-Brown C, Baratta JM, et al. Coding long COVID: characterizing a new disease through an ICD-10 lens. BMC Med. 2023;21:58. doi:10.1186/s12916-023-02737-6

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Jaywant A, Gunning FM, Oberlin LE, et al. Cognitive symptoms of post–COVID-19 condition and daily functioning. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(2):e2356098. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.56098

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Taquet M, Geddes JR, Husain M, Luciano S, Harrison PJ. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(5):416-427. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00084-5 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hampshire A, Trender W, Chamberlain SR, et al. Cognitive deficits in people who have recovered from COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;39:101044. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101044

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38:101019. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Ahmed GK, Khedr EM, Hamad DA, Meshref TS, Hashem MM, Aly MM. Long term impact of Covid-19 infection on sleep and mental health: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2021;305:114243. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114243

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Riedel B, Horen SR, Reynolds A, Hamidian Jahromi A. Mental health disorders in nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications and coping strategies. Front Public Health. 2021;9:707358. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.707358

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Hampshire A, Chatfield DA, MPhil AM, et al. Multivariate profile and acute-phase correlates of cognitive deficits in a COVID-19 hospitalised cohort. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;47:101417. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101417

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Badenoch JB, Rengasamy ER, Watson C, et al. Persistent neuropsychiatric symptoms after COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Commun. 2021;4(1):fcab297. doi:10.1093/braincomms/fcab297

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Crivelli L, Palmer K, Calandri I, et al. Changes in cognitive functioning after COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(5):1047-1066. doi:10.1002/alz.12644

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Ley H, Skorniewska Z, Harrison PJ, Taquet M. Risks of neurological and psychiatric sequelae 2 years after hospitalisation or intensive care admission with COVID-19 compared to admissions for other causes. Brain Behav Immun. 2023;112:85-95. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2023.05.014

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Taquet M, Skorniewska Z, De Deyn T, et al. Cognitive and psychiatric symptom trajectories 2-3 years after hospital admission for COVID-19: a longitudinal, prospective cohort study in the UK. Lancet Psychiatry. 2024;11(9):696-708. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(24)00214-1

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Hampshire A, Azor A, Atchison C, et al. Cognition and Memory after Covid-19 in a Large Community Sample. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(9):806-818. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2311330

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Seighali N, Abdollahi A, Shafiee A, et al. The global prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disorder among patients coping with Post COVID-19 syndrome (long COVID): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24(1):105. doi:10.1186/s12888-023-05481-6

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Meca-García JM, Perní-Lasala MT, Parrón-Carreño T, Lozano-Paniagua D, Castro-Luna G, Nievas-Soriano BJ. Neuropsychiatric symptoms of patients two years after experiencing severe COVID-19: A mixed observational study. Med Clin (Barc). 2024;163(8):383-390. doi:10.1016/j.medcli.2024.05.002

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Chau SWH, Chue TM, Chan RNY, et al. Chronic post-COVID neuropsychiatric symptoms persisting beyond one year from infection: a case-control study and network analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2024;14(1):261. doi:10.1038/s41398-024-02978-w

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Yasir S, Jin Y, Razzaq FA, et al. The determinants of COVID-induced brain dysfunctions after SARS-CoV-2 infection in hospitalized patients. Front Neurosci. 2024;17:1249282. doi:10.3389/fnins.2023.1249282

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Elboraay T, Ebada MA, Elsayed M, et al. Long-term neurological and cognitive impact of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis in over 4 million patients. BMC Neurol. 2025;25(1):250. doi:10.1186/s12883-025-04174-9

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Panagea E, Messinis L, Petri MC, et al. Neurocognitive Impairment in Long COVID: A Systematic Review. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2025;40(1):125-149. doi:10.1093/arclin/acae042

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Araújo N, Silva I, Campos P, et al. Cognitive impairment 2 years after mild to severe SARS-CoV-2 infection in a population-based study with matched-comparison groups. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):24335. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-96608-0

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Paccagnella O, Miele F, Guzzon A, et al. Effects of COVID-19 nursing home restrictions on people with dementia involved in a supportive care programme. Front Health Serv. 2024;4:1440080. doi:10.3389/frhs.2024.1440080

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Georgousopoulou V, Pervanidou P, Perdikaris P, et al. COVID-19 pandemic? mental health implications among nurses and proposed interventions. AIMS Public Health. 2024;11(1):273-293. doi:10.3934/publichealth.2024014

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - NHS England. Long COVID patients to get help at more than 60 clinics. Published December 18, 2020. Accessed December 17, 2025.

Long COVID patients to get help at more than 60 clinics - Luo S, Zheng Z, Bird SR, et al. An Overview of Long COVID Support Services in Australia and International Clinical Guidelines, With a Proposed Care Model in a Global Context. Public Health Rev. 2023;44:1606084. doi:10.3389/phrs.2023.1606084

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Long-COVID Alliance. Directory of Long COVID Clinics. Long-COVID Alliance. Published May 11, 2023. Accessed November 30, 2025.

Directory of Long COVID Clinics - Adam LC, Boesl F, Raeder V, et al. The legacy of the COVID-19 pandemic for the healthcare environment: the establishment of long COVID/ Post-COVID-19 condition follow-up outpatient clinics in Germany. BMC Health Serv Res. 2025;25(1):360. doi:10.1186/s12913-025-12521-2

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Patel MP, Schettini P, O’Leary CP, Bosworth HB, Anderson JB, Shah KP. Closing the Referral Loop: an Analysis of Primary Care Referrals to Specialists in a Large Health System. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):715-721. doi:10.1007/s11606-018-4392-z

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - McIntyre D, Chow CK. Waiting Time as an Indicator for Health Services Under Strain: A Narrative Review. Inquiry. 2020;57:46958020910305. doi:10.1177/0046958020910305

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Limiri DM. The impact of long wait times on patient health outcomes: the growing NHS crisis. Premier Journal of Public Health. 2025;3:100020. doi:10.70389/PJPH.100020 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bailey J, Lavelle B, Miller J, et al. Multidisciplinary center care for long COVID syndrome a retrospective cohort study. Am J Med. 2023. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.05.002

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Accorroni A, Nencha U, Bègue I. The interdisciplinary synergy between neurology and psychiatry: advancing brain health. Clinical and Translational Neuroscience. 2025;9(1):18. doi:10.3390/ctn9010018

Crossref | Google Scholar - Barshikar S, Laguerre M, Gordon P, Lopez M. Integrated care models for long coronavirus disease. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2023. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2023.03.007

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Bodaghi A, Fattahi N, Ramazani A. Biomarkers: promising and valuable tools towards diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of COVID-19 and other diseases. Heliyon. 2023;9(2):e13323. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13323

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Huang Z, Haile K, Gedefaw L, et al. Blood Biomarkers as Prognostic Indicators for Neurological Injury in COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(21):15738. doi:10.3390/ijms242115738

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Guillén N, Pérez-Millan A, Falgàs N, et al. Cognitive profile, neuroimaging and fluid biomarkers in post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):12927. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-63071-2

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Samadzadeh S, Sleator RD. The role of neurofilament light (NfL) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in MS and AQP4-NMOSD: advancing clinical applications. eNeurologicalSci. 2025;38:100550. doi:10.1016/j.ensci.2025.100550

Crossref | Google Scholar - Henderson C, Evans-Lacko S, Thornicroft G. Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):777-780. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301056

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Stuart H. Reducing the stigma of mental illness. Glob Ment Health (Camb). 2016;3:e17. doi:10.1017/gmh.2016.11

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Callard F, Perego E. How and why patients made Long Covid. Soc Sci Med. 2021;268:113426. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113426

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Morris K, Parmar J, Torres A, Kamal TT. Balancing ethics and efficacy: examining the scope of artificial intelligence in neurocognitive rehabilitation (P4-4.004). Neurology. 2025;104(7 Suppl 1):3037. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000210752

Crossref | Google Scholar - Topol EJ. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019;25(1):44-56. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0300-7

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Weix NM, Shake HM, Duran Saavedra AF, et al. Cognitive Interventions and Rehabilitation to Address Long-COVID Symptoms: A Systematic Review. OTJR (Thorofare N J). doi:10.1177/15394492251328310

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

Not reported

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Kevin Morris

Department of Research and Development, Aklun Biotech, Nagpur, India

Editor-in-Chief, Medtigo Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry, USA

Morris Lifesciences and Technologies, Research Center, Nagpur, India

Email: morriskevin2508@gmail.com

Co-Author:

Walencia Olympia Pereira

College of Nursing and Health Sciences, Azusa Pacific University, California, USA

Authors Contributions

WOP and KM contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. WOP and KM were involved in the Original Draft preparation, and Writing, Review & Editing to refine the manuscript. KM oversaw the Supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. WOP and KM approved the final manuscript for submission to the journal.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Guarantor

The guarantor of this study was Kevin Morris, MD

DOI

Cite this Article

Pereira WO, Morris K. The Neuropsychiatric Fallout of Long COVID: Clinical, Biological, and Health-System Readiness Challenges. medtigo J Neurol Psychiatr. 2025;2(4):e3084243. doi:10.63096/medtigo3084243 Crossref