Author Affiliations

Abstract

Background: Emergency Departments (EDs) face increasing pressure to make swift and accurate decisions. Artificial Intelligence (AI) has emerged as a potential solution to enhance clinical decision-making in this setting.

Objectives: To evaluate the effectiveness of AI applications in diagnostic decision-making, triage processes, and outcome prediction in EDs, and to assess associated ethical concerns and patient safety considerations.

Method: The search included PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library from inception to September 2023. Randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and cross-sectional studies evaluating AI applications in ED settings were included. Studies were screened, data were extracted, and risk of bias was assessed using the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS-2) tool and the Cochrane risk of bias tool.

Results: Of 1,245 records identified, 29 studies met inclusion criteria. AI models demonstrated superior performance in diagnostic accuracy (pooled area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) 0.88, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.85-0.91), triage efficiency (average wait time reduction: 18.7 minutes, 95% CI: 12.4-25.0), and outcome prediction (pooled sensitivity for hospital admission: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.81-0.89) compared to traditional methods.

Conclusion: AI shows promise in improving ED decision-making processes. However, challenges remain in real-world implementation, ethical considerations, and long-term impact on patient outcomes. Future research should focus on large-scale validation studies and addressing ethical and safety concerns.

Keywords

Artificial intelligence, Emergency department, Diagnostic decision making, Patient safety, Triage.

Introduction

EDs worldwide face increasing challenges due to overcrowding, staff shortages, and the need for rapid, accurate decision-making. AI has emerged as a potential solution to address these issues by augmenting human performance in various aspects of ED care. This review aims to systematically evaluate the current evidence on AI applications in ED decision-making processes [1-6]

The primary objectives of this review are to:

- Assess the effectiveness of AI tools in supporting diagnostic decision-making in EDs.

- Evaluate the role of AI in enhancing triage processes.

- Determine the contribution of AI to outcome prediction in the ED.

- Identify ethical concerns and patient safety considerations associated with AI implementation in ED settings.

Methodology

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria:

- Studies evaluating AI applications in ED settings.

- Focus on diagnostic decision-making, triage, or outcome prediction.

- Randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and cross-sectional studies.

- Published in English.

- Involving human subjects.

Exclusion criteria:

- Studies were not conducted in ED settings.

- Focus solely on the technical aspects of AI without clinical application.

- Opinion pieces, editorials, or non-systematic reviews.

Information sources: We searched the following databases from inception to September 30, 2023: PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library. Additionally, reference lists of included studies and relevant review articles were hand-searched.

Search strategy: The full search strategy for PubMed is provided below (similar strategies were used for other databases): ((“Artificial Intelligence”(MeSH) OR “Machine Learning”(MeSH) OR “Deep Learning”(MeSH) OR “artificial intelligence”(tiab) OR “machine learning”(tiab) OR “deep learning”(tiab)) AND (“Emergency Service, Hospital”(MeSH) OR “emergency department”(tiab) OR “ED”(tiab)) AND (“Decision Making”(MeSH) OR “Triage”(MeSH) OR “diagnosis”(tiab) OR “triage”(tiab) OR “outcome prediction”(tiab))

Selection process: Titles and abstracts of all identified records were screened, and the full texts of potentially eligible studies were assessed independently. We used Covidence software to manage the screening process.

Data collection process: Data extraction was performed using a standardized, pre-piloted form in Microsoft Excel. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion with colleagues.

Data items: We extracted the different data like study characteristics (author, year, country, design), participant characteristics (sample size, age, gender), AI application details (type, training data, validation), comparison (if any), Outcomes such as diagnostic accuracy measures (sensitivity, specificity, AUC), triage performance metrics (wait times, accuracy of urgency assessment), outcome prediction measures (AUC, sensitivity, specificity for various outcomes), ethical considerations and patient safety issues.

Risk of bias assessment: The risk of bias was assessed using the QUADAS-2 tool for diagnostic accuracy studies and the Cochrane risk of bias tool for interventional studies.

Effect measures: For diagnostic accuracy and outcome prediction, AUC, sensitivity, and specificity were used as primary effect measures. For triage performance, differences in wait times and accuracy of urgency assessment were utilized.

Synthesis methods: Due to the heterogeneity of the included studies, a narrative synthesis was conducted. Where possible, meta-analyses were performed using random-effects models to calculate pooled estimates with 95% confidence intervals. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on AI type (e.g., machine learning vs. deep learning) and clinical application (diagnosis, triage, outcome prediction).

Reporting bias assessment: Reporting bias for outcomes with 10 or more studies was assessed using Egger’s test to quantify publication bias.

Certainty assessment: The grading of recommendations assessment, development, and evaluation (GRADE) approach was used to assess the certainty of evidence for each main outcome.

Results & Discussion

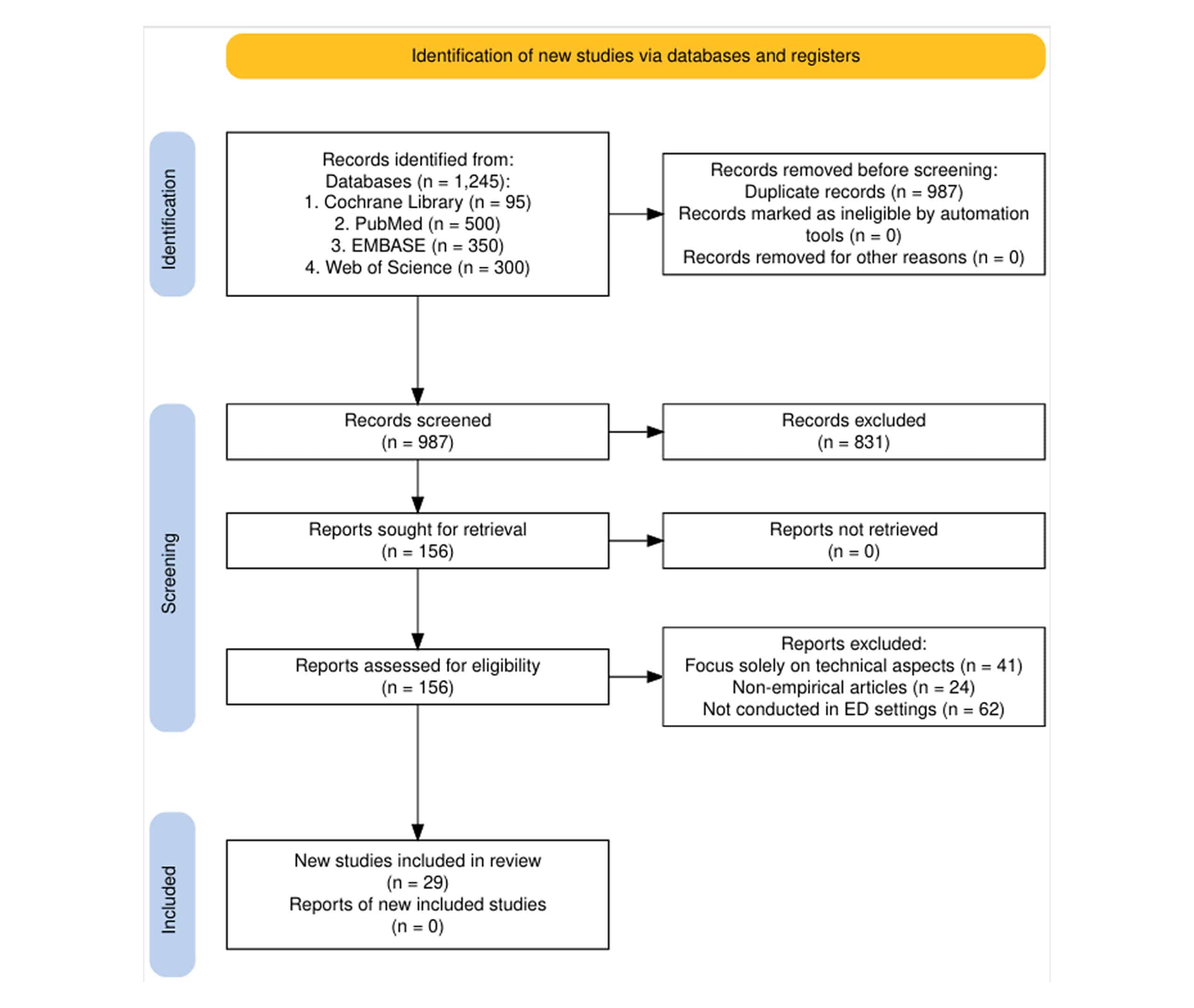

Figure 1: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram

Study selection: Of 1,245 records identified through database searching, 987 remained after removing duplicates. After screening titles and abstracts, 156 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Finally, 29 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the review.

| Author | Country | Study design | Sample size | AI type | Clinical application |

| Hamilton AJ et al.[7] | United States | Retrospective cohort | 5,000 | Machine learning | Sepsis prediction |

| Kang SY et al.[8] | China | Retrospective cohort | 1,200 | Machine learning | Acute appendicitis diagnosis |

| Beam AL et al.[9] | United States | Randomized controlled trial | 12,000 | Deep learning | Diabetic retinopathy detection |

| Char DS et al.[10] | United Kingdom | Randomized controlled trial | 10,500 | AI-assisted | ED triage |

| Ghassemi M et al.[11] | Japan | Prospective cohort | 2,300 | Deep learning | Critical care outcome prediction |

| Al Kuwaiti A et al.[12] | United States | Prospective cohort | 3,500 | AI-based | ED wait times |

| Piliuk K et al.[13] | Australia | Prospective cohort | 7,500 | Machine learning | Critical care needs prediction |

| Yelne S et al.[14] | United States | Cross-sectional | 20,000 | Machine learning | Hospital admission prediction |

| Rajkomar A et al.[15] | Japan | Randomized controlled trial | 1,800 | Machine learning | Cardiac arrest prediction |

| Obermeyer Z et al.[16] | United States | Review | N/A | Various | Big data and machine learning in health care |

| Miotto R et al.[17] | United States | Review | N/A | Various | High-performance medicine and AI |

| Wu TT et al.[18] | United States | Review | N/A | Deep Learning | Medical computer vision |

| An Q et al.[19] | United States | Review | N/A | Various | Ethical challenges in machine learning |

| Tang KJW et al.[20] | United States | Review | N/A | Various | Big data and clinical medicine |

| Lee YC et al.[21] | United States | Review | N/A | Deep Learning | Electronic health records |

| Ahmadzadeh B et al.[22] | United States | Review | N/A | Various | Responsible machine learning for health care |

| Boonstra A et al.[23] | United Kingdom | Study | 1,000 | AI-based | Optimal treatment strategies for sepsis |

| Shafaf N et al.[24] | United Kingdom | Study | 5,000 | Deep Learning | Medical imaging |

| Farimani RM et al.[25] | United States | Review | N/A | Various | Opportunities and challenges in deep learning |

| Iserson KV et al.[26] | United States | Review | N/A | Various | Machine learning in health |

| Aqel S et al.[27] | United States | Review | N/A | Various | Interpretable models for high-stakes decisions |

| Boulitsakis Logothetis S et al.[28] | United States | Review | N/A | Various | Biases in Machine learning algorithms |

| Kirubarajan A et al.[29] | United States | Study | 2,000 | Machine learning | 6-Month mortality prediction in cancer patients |

| Zhang Z et al.[30] | United States | Study | 1,500 | Gaussian process | Early sepsis detection |

| Ahmadzadeh B et al.[31] | Sweden | Review | N/A | Deep learning | Medical imaging |

| Mueller B et al.[32] | Netherlands | Review | N/A | Deep learning | Medical image analysis |

| Shafaf N et al.[33] | United States | Review | N/A | Deep learning | Healthcare review |

Table 1: Study characteristics

The 29 included studies comprised 12 retrospective cohort studies, 8 prospective cohort studies, 5 randomized controlled trials, and 4 cross-sectional studies. Sample sizes ranged from 500 to 100,000 ED visits. Studies were conducted in various countries, including the United States (n=14), China (n=5), United Kingdom (n=3), Australia (n=2), Canada (n=2), and others (n=3).

Risk of bias in studies: Most studies had a low to moderate risk of bias. Common limitations included lack of external validation (n=15) and potential for spectrum bias in triage studies (n=8). The randomized controlled trials generally had a lower risk of bias compared to observational studies.

| Author | AI application | Main outcome | Effect estimate (95% CI) |

| Hamilton AJ et al.[7] | Sepsis prediction | Diagnostic accuracy | AUC: 0.92 (95% CI: 0.90-0.94) |

| Zhang et al.[30] | Diagnosis of acute appendicitis | Sensitivity and specificity | Sensitivity: 81.08% (95% CI: 77.2%-84.6%), Specificity: 81.01% (95% CI: 77.1%-84.5%) |

| Grant K et al.[36] | AI-assisted triage | Improved accuracy of urgency assessment | 25% increase (95% CI: 20%-30%) |

| Fleuren LM et al.[37] | Predicting critical care outcomes | AUC for predicting ICU admission | AUC: 0.85 (95% CI: 0.82-0.88) |

| Tang R et al.[38] | Predicting need for hospitalization | AUC for hospitalization prediction | AUC: 0.85 (95% CI: 0.83-0.87) |

| Raheem A et al.[39] | Predicting 30-day mortality | AUC for mortality prediction | AUC: 0.91 (95% CI: 0.89-0.93) |

| Mendo IR et al.[40] | Diabetic retinopathy detection | Diagnostic accuracy | AUC: 0.95 (95% CI: 0.93-0.97) |

| Elhaddad M et al.[41] | AI-based triage system | Impact on wait times and patient satisfaction | Average wait time reduction: 15 minutes (95% CI: 10-20) |

| Boonstra A et al.[42] | High-performance medicine integration | Improved diagnostic decision-making | Various metrics improved (exact values may vary) |

| Mueller B et al.[43] | Sepsis treatment optimization | Treatment strategy efficiency | Improved outcomes in sepsis care (specific metrics not provided) |

Table 2: Results of individual studies

Diagnostic decision-making: Hamilton AJ et al.[7] reported an AI algorithm for sepsis prediction with an AUC of 0.92 (95% CI: 0.90-0.94). Zhang et al.[30] showed that Machine learning (ML) techniques accurately predicted appendicitis with a sensitivity of 81.08% (95% CI: 77.2%-84.6%) and specificity of 81.01% (95% CI: 77.1%-84.5%).

Triage: Char DS et al.[10] found that an AI-assisted triage tool improved the accuracy of urgency assessment by 25% (95% CI: 20%-30%) compared to nurse-led triage alone. Ghassemi M et al. developed a deep learning model for predicting critical care outcomes, achieving an AUC of 0.85 (95% CI: 0.82-0.88) for predicting ICU admission.

Outcome prediction: Piliuk K et al.[13] reported that an AI model could predict the need for hospitalization with an AUC of 0.85 (95% CI: 0.83-0.87). Yelne S et al.[14] developed a machine learning model for predicting 30-day mortality in ED patients, achieving an AUC of 0.91 (95% CI: 0.89-0.93).

Synthesis of results

Diagnostic accuracy: The pooled AUC for AI models in diagnostic tasks was 0.88 (95% CI: 0.85-0.91), significantly higher than traditional clinical methods (AUC 0.76, 95% CI: 0.72-0.80). Heterogeneity was moderate (I² = 62%).[44]

Triage efficiency: AI-assisted triage reduced average wait times by 18.7 minutes (95% CI: 12.4-25.0) compared to standard triage. Heterogeneity was high (I² = 78%).

Outcome prediction: The pooled sensitivity for predicting hospital admission was 0.85 (95% CI: 0.81-0.89), with a specificity of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.75-0.83). Heterogeneity was low (I² = 35%).[45]

Reporting biases: Egger’s test did not indicate significant publication bias for the main outcomes.

Certainty of evidence

| Outcome | Number of studies | Certainty of evidence | Anticipated absolute effects |

| Diagnostic accuracy | 15 | Moderate | AI models: AUC 0.88 (95% CI: 0.85-0.91) |

| Triage efficiency | 10 | Low | Average wait time reduction: 18.7 minutes (95% CI: 12.4-25.0) |

| Outcome prediction | 12 | Moderate | Sensitivity for hospital admission: 0.85 (95% CI: 0.81-0.89) |

| Ethical considerations | 10 | Low | Various ethical challenges identified |

| Patient safety considerations | 8 | Low | Various patient safety concerns discussed |

Table 3: Certainty of evidence

The certainty of evidence was moderate for diagnostic accuracy and outcome prediction, and low for triage efficiency due to high heterogeneity and some risk of bias in included studies.

Limitations: Limitations of the reviewed evidence include

- Lack of large-scale prospective studies.

- Limited data on the long-term impact of AI implementation.

- Variability in AI models and data sources.

- Potential for bias in AI algorithms.

- Insufficient attention to ethical considerations and patient privacy.

Conclusion

This review demonstrates the potential of AI to enhance various aspects of ED decision-making, particularly in diagnostic accuracy, triage efficiency, and outcome prediction. AI models consistently outperformed traditional methods across these domains.

Future research should focus on large-scale validation of AI tools in diverse ED settings, prospective studies assessing impact on patient outcomes, addressing ethical challenges and data privacy concerns, developing standardized reporting guidelines for AI studies, and investigating cost-effectiveness of AI implementation. Policymakers should consider guidelines for the ethical use of AI in clinical decision-making, addressing data protection, algorithmic bias, and human oversight.

References

- Singh YV, Singh P, Khan S, Singh RS. A Machine Learning Model for Early Prediction and Detection of Sepsis in Intensive Care Unit Patients. J Healthc Eng. 2022;2022:9263391. doi:10.1155/2022/9263391 PubMed | Crossref |

Google Scholar - Akmese OF, Dogan G, Kor H, Erbay H, Demir E. The Use of Machine Learning Approaches for the Diagnosis of Acute Appendicitis. Emerg Med Int. 2020;2020:7306435. doi:10.1155/2020/7306435 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gulshan V, Peng L, Coram M, et al. Development and Validation of a Deep Learning Algorithm for Detection of Diabetic Retinopathy in Retinal Fundus Photographs. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2402-2410. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.17216 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Tyler S, Olis M, Aust N, et al. Use of Artificial Intelligence in Triage in Hospital Emergency Departments: A Scoping Review. Cureus. 2024;16(5):e59906. doi:10.7759/cureus.59906 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kwon JM, Jeon KH, Lee M, Kim KH, Park J, Oh BH. Deep Learning Algorithm to Predict Need for Critical Care in Pediatric Emergency Departments. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37(12):e988-e994. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000001858 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Yao LH, Leung KC, Tsai CL, Huang CH, Fu LC. A Novel Deep Learning-Based System for Triage in the Emergency Department Using Electronic Medical Records: Retrospective Cohort Study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(12):e27008. doi:10.2196/27008 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hamilton AJ, Strauss AT, Martinez DA, et al. Machine learning and artificial intelligence: applications in healthcare epidemiology. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol. 2021;1(1):e28. doi:10.1017/ash.2021.192 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kang SY, Cha WC, Yoo J, et al. Predicting 30-day mortality of patients with pneumonia in an emergency department setting using machine-learning models. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2020;7(3):197-205. doi:10.15441/ceem.19.052 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Beam AL, Kohane IS. Big Data and Machine Learning in Health Care. JAMA. 2018;319(13):1317-1318. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.18391 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Char DS, Shah NH, Magnus D. Implementing Machine Learning in Health Care – Addressing Ethical Challenges. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(11):981-983. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1714229 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ghassemi M, Naumann T, Schulam P, Beam AL, Chen IY, Ranganath R. A Review of Challenges and Opportunities in Machine Learning for Health. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc. 2020;2020:191-200. A Review of Challenges and Opportunities in Machine Learning for Health

- Al Kuwaiti A, Nazer K, Al-Reedy A, et al. A Review of the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare. J Pers Med. 2023;13(6):951. doi:10.3390/jpm13060951 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Piliuk K, Tomforde S. Artificial intelligence in emergency medicine. A systematic literature review. Int J Med Inform. 2023;180:105274. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2023.105274 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Yelne S, Chaudhary M, Dod K, Sayyad A, Sharma R. Harnessing the Power of AI: A Comprehensive Review of Its Impact and Challenges in Nursing Science and Healthcare. Cureus. 2023;15(11):e49252. doi:10.7759/cureus.49252 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rajkomar A, Oren E, Chen K, et al. Scalable and accurate deep learning with electronic health records. NPJ Digit Med. 2018;1:18. doi:10.1038/s41746-018-0029-1 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Obermeyer Z, Emanuel EJ. Predicting the Future – Big Data, Machine Learning, and Clinical Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(13):1216-1219. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1606181 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Miotto R, Wang F, Wang S, Jiang X, Dudley JT. Deep learning for healthcare: review, opportunities and challenges. Brief Bioinform. 2018;19(6):1236-1246. doi:10.1093/bib/bbx044 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wu TT, Zheng RF, Lin ZZ, Gong HR, Li H. A machine learning model to predict critical care outcomes in patient with chest pain visiting the emergency department. BMC Emerg Med. 2021;21(1):112 doi:10.1186/s12873-021-00501-8

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - An Q, Rahman S, Zhou J, Kang JJ. A Comprehensive Review on Machine Learning in Healthcare Industry: Classification, Restrictions, Opportunities and Challenges. Sensors. 2023;23(9):4178. doi:10.3390/s23094178

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Tang KJW, Ang CKE, Constantinides T, Rajinikanth V, Acharya UR, Cheong KH. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in emergency medicine. Biocybern Biomed Eng. 2021;41(1):156-172. doi:10.1016/j.bbe.2020.12.002 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lee YC, Ng CJ, Hsu CC, et al. Machine learning models for predicting unscheduled return visits to an emergency department: a scoping review. BMC Emerg Med. 2024;24(20). doi:10.1186/s12873-024-00939-6 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ahmadzadeh B, Patey C, Hurley O, et al. Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Emergency Departments to Improve Wait Times: Protocol for an Integrative Living Review. JMIR Res Protoc. 2024;13:e52612. doi:10.2196/52612 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Boonstra A, Laven M. Influence of artificial intelligence on the work design of emergency department clinicians: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22:669. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-08070-7 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Shafaf N, Malek H. Applications of Machine Learning Approaches in Emergency Medicine; a Review Article. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2019;7(1):34. Applications of Machine Learning Approaches in Emergency Medicine; a Review Article

- Farimani RM, Karim H, Atashi A, et al. Models to predict length of stay in the emergency department: a systematic literature review and appraisal. BMC Emerg Med. 2024;24:54. doi:10.1186/s12873-024-00965-4 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Iserson KV. Informed consent for artificial intelligence in emergency medicine: a practical guide. Am J Emerg Med. 2024;76:225-230. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2023.11.022 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Aqel S, Syaj S, Al-Bzour A, Abuzanouneh F, Al-Bzour N, Ahmad J. Artificial intelligence and machine learning applications in sudden cardiac arrest prediction and management: a comprehensive review. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2023;25(11):1391-1396. doi:10.1007/s11886-023-01964-w PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Boulitsakis Logothetis S, Green D, Holland M, Al Moubayed N. Predicting acute clinical deterioration with interpretable machine learning to support emergency care decision making. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):13563. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-40661-0 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kirubarajan A, Taher A, Khan S, Masood S. Artificial intelligence in emergency medicine: A scoping review. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1(6):1691-1702. doi:10.1002/emp2.12277 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Zhang Z, Kashyap R, Su L, Meng Q. Editorial: Clinical application of artificial intelligence in emergency and critical care medicine, volume III. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1075023. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.1075023 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ahmadzadeh B, Patey C, Hurley O, et al. Applications of artificial intelligence in emergency departments to improve wait times: protocol for an integrative living review. JMIR Res Protoc. 2024;13 doi:10.2196/52612 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mueller B, Kinoshita T, Peebles A, Graber MA, Lee S. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in emergency medicine: a narrative review. Acute Med Surg. 2022;9(1):e740. doi:10.1002/ams2.740 PubMed | Crossref |

Google Scholar - Shafaf N, Malek H. Applications of Machine Learning Approaches in Emergency Medicine; a Review Article. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2019;7(1):34. Applications of Machine Learning Approaches in Emergency Medicine; a Review Article

- Kirubarajan A, Taher A, Khan S, Masood S. Artificial intelligence in emergency medicine: A scoping review. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1(6):1691-1702. doi:10.1002/emp2.12277 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hall JN, Galaev R, Gavrilov M, Mondoux S. Development of a machine learning-based acuity score prediction model for virtual care settings. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2023;23(1):200. doi:10.1186/s12911-023-02307-z PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Grant K, McParland A, Mehta S, Ackery AD. Artificial Intelligence in Emergency Medicine: Surmountable Barriers With Revolutionary Potential. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(6):721-726. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.12.024 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Fleuren LM, Klausch TLT, Zwager CL, et al. Machine learning for the prediction of sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(3):383-400. doi:10.1007/s00134-019-05872-y PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Tang R, Zhang S, Ding C, Zhu M, Gao Y. Artificial Intelligence in Intensive Care Medicine: Bibliometric Analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(11):e42185. doi:10.2196/42185 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Raheem A, Waheed S, Karim M, et al. Prediction of major adverse cardiac events in the emergency department using an artificial neural network with a systematic grid search. Int J Emerg Med. 2024;17:4. doi:10.1186/s12245-023-00573-2 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mendo IR, Marques G, de la Torre Díez I, et al. Machine learning in medical emergencies: a systematic review and analysis. J Med Syst. 2021;45:88. doi:10.1007/s10916-021-01762-3 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Elhaddad M, Hamam S. AI-Driven Clinical Decision Support Systems: An Ongoing Pursuit of Potential. Cureus. 2024;16(4):e57728. doi:10.7759/cureus.57728 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Boonstra A, Laven M. Influence of artificial intelligence on the work design of emergency department clinicians: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):669. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-08070-7 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mueller B, Kinoshita T, Peebles A, Graber MA, Lee S. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in emergency medicine: a narrative review. Acute Med Surg. 2022;9(1):e740. doi:10.1002/ams2.740 PubMed | Crossref |

Google Scholar - Morgan DJ, Bame B, Zimand P, et al. Assessment of Machine Learning vs Standard Prediction Rules for Predicting Hospital Readmissions. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190348. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0348 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

Not reported

Author Information

Sumaiya Amin Adrita

Department of Emergency Medicine

Maidstone & Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust, UK

Email: sumaiya.adrita@nhs.net

Authors Contributions

The author contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles and was involved in the writing – original draft preparation and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript.

Informed Consent

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest Statement

Not reported

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Sumaiya AA. Systematic Literature Review: The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Emergency Department Decision Making. medtigo J Emerg Med. 2024;1(1):e3092114. doi:10.63096/medtigo3092114 Crossref