Author Affiliations

Abstract

Owing to the ecological difficulties instigated by the use of petroleum, significant consideration has been given to biodiesel manufacture as a substitute. Biofuel is a degradable and environmentally friendly substitute for diesel oil produced from renewable sources such as vegetable oil, animal fats, and vegetable oils. They are a renewable source of energy, which appears to be a perfect way out for international energy difficulties. The common technique to yield biofuel is the trans-esterification process of nonpalatable oil in conjunction with an alcohol, usually methanol, accompanied by a catalyst, which could be a base or an acid. The trans-esterification process is relatively delicate to numerous factors such as the viscosity, time, and temperature of the reaction, density, flash point, etc. This paper review defines the manufacturing procedure, which is commonly known as the trans-esterification process, several alternatives of nonpalatable oils as a considerable source of raw material, and a crucial parameter that defines the quality of a given biodiesel.

Keywords

Biofuel, Biodiesel, Vegetable oil, Trans-esterification process, Nonpalatable oil.

Introduction

Biofuel is a renewable, safer substitute for fuel whose source its raw material from plants (fruits and seeds) and animal fats. Owing to the tremendous elevation in environmental pollution as well as the cost of oil from petroleum sources, biodiesel has turned out to be the best prospective fuel due to numerous benefits, e.g its effectiveness and its eco-friendly potential over petroleum fuel.[1] Countless nation states across the world are making efforts to enlarge the exploitation of biofuel in their industrialization. Persistent use of fuels from petroleum as a basis for generating energy is now extensively documented as unsustainable due to its diminishing deliveries, and the negative impact of this oil on the excessive and constant carbon dioxide emission into the atmosphere is an issue of serious concern within society and the world at large.[2] Biofuel can be used either in its pure form or blended with conventional diesel oil, depending on the engine type and fuel system requirements.

Trans-esterification is a process by which non palatable oils (jatropha, alga, mango, soap nut, neem oil etc.) and palatable oil such as soya beans, groundnut, palm oil etc. are transformed with the aid of alcohol usually methanol in the presence of an acid (H2SO4) or base (KOH/NaOH) as a catalytic agent, glycerin is given out as a waste material.[3]

Biofuel is a favorable substitute source of fuel with profits over crude oil fuel source, for example, a low amount of sulfur, ability to biodegrade, renewability, high burning efficacy, and eco-friendliness etc.[2-4] It decreases the engine degrading process, thus elevating the lifespan of fuel pumping utensils and advancing the excellence of the surroundings with a pleasurable fruity odor, with a smaller amount of smoke produced in the vehicle or engine exhaust.[5] Minute particulate matter is produced by biofuel, truncated idle noise, and stress-free cold ignition while in use.[6] Likewise, establish that biofuel has a great lubricating ability, more than all other fuels, is less poisonous, safer to transport due to its elevated flash point, oxidative stability, and higher cetane number compared to conventional diesel, and has minimal emission of carbon soot and other toxic organic substances.[7]

Manufacturing Process of Biodiesel

Vegetal oils are multifaceted fatty acids (esters). These are fats obtained from oil-containing seeds and identified as triglycerides (fatty acids). The weight of the molecule, i.e, triglycerides, is around 800kgm-3 and above. Due to their large molecular mass, these oils have high viscosity, which negatively affects their performance as fuel in engines.

However, there is a significant need to crack it into a lighter weight molecule, which in turn lessens the opposition in the flow of the oil, which possesses properties like those of commercially used diesel oil. Transforming the vegetal oils into a less viscous product could be reached in voluminous means, such as Trans-esterification, Pyrolysis, Dilution, and Micro-emulsification. However, the technique that is often applied to produce biofuel on an industrial scale is the trans-esterification technique, which tends to yield a product (lighter oil) that is environmentally non-toxic.[8]

Transesterification: Biofuel, a substitute fuel (diesel) obtained via trans-esterification, is the process of converting oil chemically to its resultant fatty ester using a catalyst. This process translates esters from longer-chain fatty acids to short-chain fatty acids (alkyl esters). Trans-esterification procedure helps diminish the resistance in oil flow. This reaction takes place effectively when a homogeneous catalyst is applied, which includes tetraoxosulphate (VI) acids, sodium hydroxide, and potassium hydroxide. The establishment of fatty acid (methyl esters) via the trans-esterification process of seed oils necessitates the availability of methanol, sodium, raw oil, and sodium hydroxide. Though trans-esterification is a reversible reaction, the presence of surplus alcohol is required to trigger the initiation of the reaction, which is also close to the finishing point.[9]

There are two major techniques suitable for the commercial fabrication of biofuel (diesel) from non-consumable oils: either base or acid-catalyzed trans-esterification.

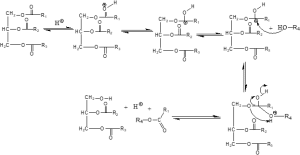

Trans-esterification process catalyzed by acid: This procedure is principally appropriate for feedstock such as crude or discarded consumable oils that possess a great amount of free fatty acids. Tetraoxosulphate (iv) acid is often used to speed up the reaction process until it comes to completion. The procedure does not necessitate treating the oil with a base to minimize the content of free fatty acids; notwithstanding, it has resulting shortcomings. It is very sluggish and desires an enormous oil/methanol molar proportion. The water formed by the response of free fatty acids alongside the alcohol constrains the process of trans-esterification of the oil (triglycerides). Excess acid can degrade oil, thereby decreasing the total quantity of biodiesel.[9-11]

Figure 1: Mechanism of trans-esterification process catalyzed by an acid (R1, R2, R3, and R4 are Alkyl groups)

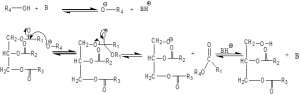

Trans-esterification process catalyzed by base: This is the old-fashioned expertise usually engaged in the marketable manufacturing process of biodiesel from vegetal sources (fat/oil) that has already undergone a refining process that has a minute free fatty acid value of less than 0.1% by weight. It includes the trans-esterification of triglycerides existing in the vegetal fat/oil with methanol, accompanied by a base catalyst, usually methanol or ethanol solution of sodium or potassium hydroxide, under atmospheric pressure and about 60 to 70 °C ethanol/methanol reflux conditions.

The mechanism of this reaction is well recognized and yields biodiesel (fatty acid methyl ester) in a quantity almost the same as the oil used, which means there is very minimal waste. The reaction is reversible and spontaneous; however, there is a need for the addition of a surplus amount of catalyst and methanol to aid the reaction to come to an end. Because this reaction is sensitive to moisture, it is vital that all required reagents are dried, most especially methanol, to ensure that the vapor content is dropped to a value less than 0.1% w/w.[11-13]

The completion of this reaction (trans-esterification), a molar proportion of triglycerides to methanol is 1:3 is required. In a real-life situation, the percentage is greater in order for the reaction to be feasible to produce an ideal yield of the ester.[13-16]

Figure 2: Mechanism of trans-esterification process catalyzed by a base (where R1, R2, R3, and R4 are Alkyl groups)

Properties of Biodiesel Fuels

Numerous factors must be investigated in others to ascertain the usability and superiority of biodiesel since they are being produced from diverse vegetable plant oils. However, the biodiesel manufactured must conform to the already existing data that indicates excellent biofuel. These factors include viscosity, flashpoint, density, cloud point/pour point, lubricity and cold flow, acid and fatty acid value, sulfated Ash and phosphorus acid, and iodine value. [10,29]

Viscosity: Viscosity of oil is a degree of its opposition to pour due to internal resistance; it is an exceedingly key factor in determining excellent biodiesel oil since it has a tremendous impact on diesel engine systems, especially during the cold season. Extremely viscous oil always leads to reduced atomization; therefore, reduced efficiency of the engine will be observed, and voluminous smoke will be generated because of incomplete combustion of diesel oil.[22,23] The viscosity of diesel generated from crude oil is considerably less viscous than that of biodiesel. This is the benefit of biodiesel as compared to its petroleum diesel source oils. Higher amount of kinematic viscidness leads to reduced biodiesel atomization, partial burning, and deposit of carbons compound on the injectors. Consequently, the oil viscidness will certainly be very low. Biodiesel fuel amalgams frequently have improved greasing capability; nevertheless, their progressive viscidness intensities lead to the formation of bigger drops on injections which eventually leads to reduced incineration and amplified exhaustion of dark smoke. Furthermore, this great viscidness engenders operating difficulties like trouble in igniting the engine, unpredictable engine starting, and weakening in thermal effectiveness. Altering biofuel is an available alternative to diminish the viscidness of vegetal oils.[22] The viscid fatty acid methyl-esters (FAME) could increase to very high altitudes, and therefore it is vital to regulate them within a suitable level to circumvent undesirable effects on the efficiency of the fuel injector system. Therefore, biodiesel thickness must always be closely equal to that of conventional diesel oil.[17,30]

Density: One of the vital properties of biodiesel is density, which unswervingly affects the performance of diesel oil engines. It upsets the amount of fuel introduced into the burning compartment; consequently, the oil is partially combusted. The quantity of diesel oil introduced or pumped is measured in volume, which means high-density oil will have more weight even though the volumes are the same. Hence, the vicissitudes in the oil density will inevitably have an adverse effect on engine productivity owing to aN unlike weight of fuel introduced or pump. It is acknowledged that biofuel thickness mostly hinges on its esters’ constituents and the lingering magnitude of alcohol; henceforth, this activity is affected chiefly by the high quality of vegetal oil.[16-18] The thickness of biofuels is a very essential oil property that disturbs the fuel pump system; the density is typically measured at a temperature of 15 °C. Density of oil is the weightiness of a part volume of liquid, but the specific gravity is said to be the proportion of the density of oil to that of water. The gas pumping apparatus measures the fuel according to volume, and greater thicknesses transform into an extraordinary ingestion of the oil. It could be understood that biodiesel possesses densities ranging from 8.60x102g/cm3 to 8.97x102g/cm3 at a temperature of 15 °C, which is greater when compared to diesel obtained from petroleum, though the high density can be understood to cover up for the low volumetric expansion constituent of the biodiesel oil.[19,22]

Flash point: The lowest temperature at which an oil sample can be ignited is recognized as the flash point of that oil sample under specialized circumstances. Flash points vary inversely with the fuel’s volatility. The flash point lowest temperatures are obligatory for appropriate welfare and management of oil. It is well-known that the biofuel constituent necessarily meets flash point standards, in combination, for the aim of assuring that the biofuel factor is methanol. The flash or ignition point of biofuel is advanced than that of crude oil diesel, however, it is safe for conveyance purposes. Raise the values of ignition point, lessening the hazard of fire.[21] Flash point of biodiesel is greater than that of petroleum diesel which implies that they are less combustible henceforth they are not dangerous to work with. Nevertheless, biodiesel possesses poorer oxidation constancy as compared to diesel obtained from crude oil and will depreciate under elongated storing owing to oxidative activity in the incidence of air.[22]

Effect of reaction temperature and time: Trans-esterification process can take place at diverse temperatures, depending on the category of oil involved. It was witnessed that elevating the temperature of the reaction, exclusively to supercritical situations, affects the yield of ester transformation positively. For the base catalytic trans-esterification process, the temperature is conserved by the scientists throughout diverse stages varying from 45oC and 65oC. Methanol has a boiling point of 64.9oC. If the reaction temperature exceeds 65°C, methanol or ethanol will evaporate, leading to a lower biodiesel yield. At temperatures above 50 °C, it is noticed that an undesirable influence on the yield of the product is observed in situations where neat oil is processed, but a helpful result is observed when waste oil has greater viscosity.[23,24] Premeditated the reaction (trans-esterification) using ethanol on oil obtained from Cynara cardunculus with potassium and sodium hydroxide (catalysts) and testified about 91.6% yield at ambient temperature. Trans-esterification catalyzed by a base on oil (Pongamia pinnata) was done at five altered temperatures with 1% concentration of the catalyst (potassium hydroxide) and 1:6 oil/methanol ratios, and the reaction took place for half an hour. The transformation was improved with intensification of the reaction temperature, and the most favorable temperature was established to be at 60°C; beyond that point, no conversion was witnessed with further intensification of temperature. The outcome of reaction time and temperature was examined on the transformation of the oil (Jatropha curcas) into biodiesel.[25] At 50°C and a reaction duration of 45 minutes, it was observed that about 93.4% of FAME was witnessed (optimal yield). The transformation methyl ester proportion rises with the progression of reaction time. Diverse scholars have testified to altered reaction intervals for the trans-esterification reaction.[26]

Phosphorus content and sulfated ash: The remaining deposit of base-catalyzed biofuel sample after carbonizing the oil is then treated with tetraoxosulphate (IV) acid and heating to a known weight. The measures of inorganic ash deposits are when a fuel undergoes the combustion process. It is an imperative examination for biofuel because it is a gauge of the amount of metal deposits in the biodiesel that occurs from the catalytic agent used during the trans-esterification reaction process. Particularly for trans-esterification (alkali catalyzed), by which KOH and NaOH are normally used, often possess truncated melting points, which may result in significant engine destruction in the burning compartment, and injector residue. The sulfur ash content is 1.0×10-1 % FAME, which is less than the standard 5.0×10-2% (mol:mol) ASTM optimum perimeter. The presence of phosphorus in biofuel comes from vegetable and animal material (phospholipids) and mineral salts enclosed in the feedstock. Phosphorus has an antagonistic effect on the elongated period of activity of exhaust discharge catalysis and, as a result, is limited by requirement. The worth of the biodiesel is not as much as the optimum of 10 mg/kg defined by the acceptable standard.[27]

Iodine number: The iodine number is the amount of overall unsaturation within a blend of fatty substances. It’s worth is determined only by the source of the vegetal oil; biodiesel obtained from the same oil would possess related iodine values.[28] It is connected to the chemical configuration of the biodiesel. Advanced iodine value designates greater non-saturation of the oil and fats. Customary iodine value for good biodiesel is 1.20 x 102 for Europe’s EN 14214 descriptions. This constraint is inadequate by the average bounds of linoleic acid methyl-ester constituent for biofuel. The restraint of non-saturated fatty acids is required owing to the circumstance that heating higher non-saturated fatty acids leads to the formation of a polymer of glycerides. However, this could result in the residue or weakening of the greasing property. Biodiesel having characteristics is most likely to yield heavy sludge in the sump of the machine when oil percolates down the edges of the compartment into the crank.[29]

The cetane number: Fuel cetane number is the amount of its ignition eminence of that fuel; the greater the amount of cetane number, the better the ignition excellence, which is theoretically comparable to octane number as used for petrol. Largely, octane and cetane numbers are inversely proportional in a given oil sample, i.e, the higher the cetane number, the lower the octane number, and vice versa. Cetane number quantifies how effortlessly ignition takes place and the smooth burning of the fuel. Cetane number upsets certain factors that indicate engine efficiency, such as durability, burning, steadiness, noise, drivability, grey smoke, production of hydrocarbon and carbon monoxide.[17] Preceding the foundation of ignition excellence, biodiesel could be alleged to be healthier than diesel obtained from petroleum origin for the reason that they have cetane numbers greater than that obtained from petroleum source; biodiesel’s advanced cetane number is a result of the greater oxygen contained in it.[30]

| Properties | Jatropha | Palm Oil | Diesel | ASTM D 6751-02 (Biodiesel Control) | DIN EN 14214 (Biodiesel Control) | Units |

| Calorific value | 3.92×10¹ | 3.35×10¹ | 4.2×10¹ | 0 | 0 | MJ/kg |

| Density | 8.80×10² | 8.80×10² | 8.50×10² | 8.70-9.0×10² | 8.75-9.0×10² | kg/m³ |

| Viscosity | 2.37 | 5.7 | 2.6 | 1.9-6.0 | 3.5-5.0 | N·m²/m |

| Sulphur | 0 | 0 | 5.00×10² | 5.0×10¹ | 5.0×10¹ | ppm |

| Cetane No. | 6.1×10¹ | 6.2×10¹ | 4.9×10¹ | 4.8-6.0×10¹ | 4.9×10¹ | – |

| Water | 2.5×10⁻² | 0 | 2.0×10⁻² | 3.0×10⁻² | 5.0×10⁻² | % |

| Flash point | 1.35×10² | 1.64×10² | 6.8×10¹ | 1.30×10² | 1.20×10² | °C |

| Cloud point | 2 | 1.2×10¹ | 4 | 0 | 0 | °C |

| Carbon residue | 2.0×10⁻¹ | 0 | 1.7×10⁻¹ | 0 | 3.0×10⁻¹ | wt% |

Table 1: Standard biodiesel and conventional diesel parameters

Purification of Biodiesel

The unfinished biofuel (FAME) comprises numerous contaminants such as water, glycerol, free fatty acid, sterol, glycerides, sterols, unsaponifiable substances, metal ions, and alcohol. The contamination is injurious to the storage of biodiesel, reservoirs, and burning engines or systems. Consequently, there are two unique approaches for washing practices to decontaminate it. [31,32]

Damp washing method: The wet or damp approach is a traditional technique that often requires continual washing of biofuel with hygienic water obtained from a good source, then the elimination of aqueous portion or phase that occurs as a result. This approach eradicates the majority of the contaminations present in the biodiesel because the bulk of them are soluble in water. The washing procedure requires 1:2 water and biodiesel volume with continues agitation at 2×103 rpm for at least 10min at ambient temperature. No additional benefits have been observed when using deionized or acidified water compared to clean tap water.

Since the ability of water to dissolve in biodiesel is about 1.5 × 10^3 mg/kg at temperatures ranging between 20 and 22°C, there is always a formation of water-FAME suspension in the wet, damp washing procedure.[33-35] For that reason, further steps are desirable to first of all demulsify the crude FAME and then remove the moisture content. Owing to these processes, damp or wet washing is more expensive and consumes a lot of time. Additionally, it is also considered not environmentally friendly due to the quantity of adulterated eluent released into the environment during the purification process.[36]

Dry washing method: In this decontamination technique, an ion exchange resin or artificial adsorbent is engaged to bind and eliminate the soaps, ionic salts, bits of catalytic agent, water and glycerin from biofuel. About three different marketable (BD10 Dry, PD206, and Magnesol®) products are in existence, which have been endorsed as an environmentally friendly substitute in biofuel manufacturing from nonpalatable oil and its properties as compared to the aqueous washing method. The three approaches eliminate soaps and glycerin effectively, except methanol, which is removed excellently only by using the wet washing method. None of the methods listed could effectively eliminate or reduce the amount of free fatty acids and glycerides in biodiesel or enhance the biofuel oxidation stability index. For the ion interchange technique, the pollutants in the feed, when existing in great amounts, can bind eternally with the bed of the resin and result in unexpected and irreparable damage to the column. The dry wash technique has a smooth particle of adsorbent that uninterruptedly elutes the column and then is detached, followed by biodiesel ultra-filtration. This increases the price and time consumption during the processing of biodiesel.[37,38] The main aim of washing biofuel is to eradicate any soap formed during the trans-esterification process. Additionally, the slightly heated adulterated water using acetic acid offers deactivation of the residual catalytic agents and eliminates the salt product. The usage of water (warm) averts agglutination of saturated FAME and delays the materialization of suspensions using a mild washing procedure. Considerably acidic water eradicates magnesium and calcium pollution and counteracts residual alkali catalysts. Mild washing averts the materialization of suspensions and leads to swift and thorough phase separation.[31]

Nonpalatable Oil-Bearing Plants

Drumstick plant (Moringa oleifera): Drum-stick plant is a perennial soft-wood tree. This plant fits into the family of monogeneric Moringaceae and is a tremendously rapidly developing plant that could grow to about 10 meters. The plant is widely and frequently nurtured in Ethiopia, South India, Sudan, the Philippines, and tropical Asia, Latin America, Florida, the Pacific Islands, and South and East Africa. It resistant to drought, lowly soil, fast growing, and can survive soil pH that is slightly acidic and basic (5.0-9.0).[39,40] It been documented that about 3.0×103 kg of drum-stick plant’s seeds can be gotten from a hectare of land, comparable to 9.0×102 kg oil per hectare, similar to soybean which also produces a similar amounts or quantity of seeds per hectare of land, however the oil yield is approximately 20%.[33] The plant seed comprises oil content ranging from 30 to 40%, liable on the plant variation and weather.[34] It oil consist of 67.7% oleic acid which is the main fatty acid succeeded by 10.7% linoleic, 8.3% stearic acid, 7.4% beheni, 6.9% palmitic, 4.7% arachidic and lastly 2.3% eicosenoic acids as examined.[39]

Kusum (Schleichera oleosa): Kusum is a moderately sized plant which matures up even 40-meters in size, which is almost green all through the year. The tree is categorized under the family of Sapindaceae that originate from South-eastern and South Asia. The berries, kernels, and fresh leaves of the plant are edible and used in making dye, as well as for medicinal purposes. The seed contained about 51 to 62% oil; however, the harvests are often within the range of 25% to 27% in oil mills and approximately 36% oil in expellers. The oil Iodine value is around 215 to 220, and the overall fatty acid present is about 91.6%.[40]

Soap nut (Sapindus mukorossi): A perennial tree known as Soap nut is classified under the family Sapindaceae, a native plant of the northern region of India.[37,44] The plant breeds well in loamy soils and percolated soils, so farming of this plant in such a soil escapes prospective soil attrition. The tree can be utilized for pastoral structure, sugar and oil presses, and farming equipment.[38] Additionally, this tree’s seed consists of 23% oil and the remaining is triglycerides.[39]

Tung (Vernicia fordii): A plant generally identified as a tung tree is a woody and oil-containing plant that fits into the family of Euphorbiaceae and originates from Burma, China, and Vietnam. It grows from a small to an average-sized tree, about 20 meters in height. The seed consists of about 21% oil, and the entire nut consists of approximately 41% oil. Typically, the plant produces roughly 450 to 600 kg of oil for every hectare of land.[42]Tung seed oil in the past had been used orthodoxly in desk lamps for illumination, also as a component for timber varnish and paint.[42] The oil predominantly comprises of the uncommon conjugated fatty acid, linoleic acid consisting about 11.50%; eleostearic acid which is also known 9,11,13-octadecatrienoic acid 63.80%; behenic, 8.4% and oleic acid, 8.60%.[43]

Syringa (Melia azedarach): A deciduous plant called syringa grows about 7 to 12 meters from the ground it is categorized under the family of mahogany of Meliaceae that is naturally found in Australia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, and Southeast Asia.[44] Only 10% of the oil is present in dried berry of syringe. Oil is described by a great proportion of unsaturated fatty acids, such as linoleic and oleic acid, at 64.1% and 21.8%, respectively. Additional components that are comprised of it that are beyond 1% are species that are saturated, e.g., palmitic and stearic acid, 10.1% and 3.5% respectively.[44]

Conclusion

Diesel oil obtained from plant and animal sources is a better substitute fuel for gas oil engines due to its renewable properties and friendliness to the environment. Numerous approaches exist for synthesizing biodiesel; however, fats and vegetable oils are most often used to carry out this process (trans-esterification) in modern days. The use of palatable oil such as groundnut, soya beans, palm oil etc. to manufacture biodiesel may result to food crisis in the nearest future, thus it would be most suitable if scientist will focus more on non-edible oil obtained from plants seeds such neem, jatropha, soup nut etc. which is readily available at low cost. The efficiency of biofuel is similar to that of diesel obtained from crude oil. Additionally, when biofuel is used in engines instead of conventional diesel, there is always minimal exhaustion of carbon monoxide into the environment. This study concludes that biodiesel is a reliable and safer alternative fuel for human use, offering environmental benefits over conventional diesel.

References

- Babadi AA, Rahmati S, Fakhlaei R et al. Emerging technologies for biodiesel production: Processes, challenges, and opportunities. Biomass Bioenergy. 2022;163:106521. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2022.106521 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kampa M, Castanas E. Human health effects of air pollution. Environ Pollut. 2008;151(2):362-367. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2007.06.012 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Van Gerpen JV. Biodiesel processing and production. Fuel Process Technol. 2005;86:1097-1107. doi:10.1016/j.fuproc.2004.11.005 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ali SS, Abdelkarim EA, Elsamahy T, et al. Bioplastic production in terms of life cycle assessment: A state-of-the-art review. Environ Sci Ecotechnol. 2023;15:100254. doi:10.1016/j.ese.2023.100254 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hill J, Nelson E, Tilman D, Polasky S, Tiffany D. Environmental, economic, and energetic costs and benefits of biodiesel and ethanol biofuels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(30):11206-11210. doi:10.1073/pnas.0604600103

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Bajpai D, Tyagi VK. Biodiesel: Source, production, composition, properties, and its benefits. J Oleo Sci. 2006;55(10):487-488. Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kamaraj R, Rao YKSS, B B. Biodiesel blends: a comprehensive systematic review on various constraints. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022;29(29):43770-43785. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-13316-8 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Raja AS, Smart DSR, Lee CR. Biodiesel production from jatropha oil and its characterization. Res J Chem Sci. 2011;1(1):81-85. Biodiesel production from jatropha oil and its characterization

- Ahmad M, Khan M, Sultana S. Biodiesel from non-edible oil seeds: A renewable source of bioenergy. 2011. doi:10.5772/24687 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Tyagi OS, Atray N, Kumar B, et al. Production, characterization, and development of standards for biodiesel: A review. 2010;25:197-218. doi:10.1007/s12647-010-0018-6 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gashaw A, Lakachew A. Production of biodiesel from non-edible oil and its properties. Int J Sci Environ Technol. 2014;3(4):1544-1562. Production of biodiesel from non edible oil and its properties

- European Commission. Bioeconomy. 2024. Bioeconomy

- Sarıbıyık O, Özcanlı M, Serin H, Serin S, Aydın K. Biodiesel production from Ricinus communis oil and its blends with soybean biodiesel. J Mech Eng. 2010;56(12):811-816. Biodiesel production from Ricinus communis oil and its blends with soybean biodiesel

- Noori W, Buthainah A, Etti C, Jassim L, Gomes C. Evaluation of different materials for biodiesel production. Int J Innov Technol Explor Eng. 2014;3:2278-3075. Evaluation of different materials for biodiesel production

- Ikeda A, Matsuura W, Abe C, Lundin S-TB, Hasegawa Y. Evaluation of FAU-type Zeolite Membrane Stability in Transesterification Reaction Conditions. Membranes. 2023; 13(1):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes13010068 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mordor Intelligence. Europe Biodiesel Market Size & Share Analysis – Growth Trends & Forecasts (2025-2030). 2025. Europe Biodiesel Market Size & Share Analysis – Growth Trends & Forecasts (2025-2030)

- Mathew GM, Raina D, Narisetty V, et al. Recent advances in biodiesel production: Challenges and solutions. Sci Total Environ. 2021;794:148751. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148751 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Encinar JM, González J, Martínez G, Sánchez N, González GC. Synthesis and characterization of biodiesel obtained from castor oil transesterification. Renew Energy Power Qual J. 2011;9:1078-1083. doi:10.24084/repqj09.549

Crossref | Google Scholar - Mehrpooya M, Ghorbani B, Karimian Bahnamiri F, Marefati M. Solar fuel production by developing an integrated biodiesel production process and solar thermal energy system. Appl Therm Eng. 2019;167:114701. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.114701 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Vuppaladadiyam VK, Sangeetha CJ, Sowmya V. Transesterification of Pongamia pinnata oil using base catalysts: A laboratory scale study. Univ J Environ Res Technol. 2013;3(1):113-118. Transesterification of Pongamia pinnata oil using base catalysts: A laboratory scale study

- Sanjay B. Non-conventional seed oils as potential feedstocks for future biodiesel industries: A brief review. Res J Chem Sci. 2013;3(5):99-103. Non-Conventional Seed Oils as Potential Feedstocks for Future Biodiesel Industries: A Brief Review

- Bashir A, Wu S, Zhu J, Krosuri A, Khan MU, Aka R. Recent development of advanced processing technologies for biodiesel production: A critical review. Fuel Process Technol. 2022;227:107120. doi:10.1016/j.fuproc.2021.107120

Crossref | Google Scholar - Leung DYC, Guo Y. Transesterification of neat and used frying oil: Optimization for biodiesel production. Fuel Process Technol. 2006;87:883-890. doi:10.1016/j.fuproc.2006.06.003 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Encinar JM, González JF, Rodriguez JJ, Tejedor A. Biodiesel fuels from vegetable oils: Transesterification of Cynara cardunculus oils with ethanol. Energy Fuels. 2002;16:443-450. Biodiesel fuels from vegetable oils: Transesterification of Cynara cardunculus L. oils with ethanol

- Vyas A, Verma J, Subrahmanyam N. Effects of molar ratio, alkali catalyst concentration, and temperature on transesterification of jatropha oil with methanol under ultrasonic irradiation. Adv Chem Eng Sci. doi:10.4236/aces.2011.12008 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kim H, Kang BS, Kim MJ, et al. Transesterification of vegetable oil to biodiesel using heterogeneous base catalyst. Catal Today. 2004;93-95:315-320. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2004.06.007 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bello EI, Agge M. Biodiesel Production from Ground Nut Oil. J Emerg Trends Eng Appl Sci. 2012;3(2):276-280. Biodiesel Production from Ground Nut Oil

- Moser B. Biodiesel production, properties, and feedstocks. In: Biodiesel: Science and Technology. 2010. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-7145-6_15 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bastioli C, Campanini L, Fumagalli S, et al. La Bioeconomia in Europa. 2023. La Bioeconomia in Europa

- Thirumarimurugan M, Sivakumar VM, Merly Xavier A, Prabhakaran D, Kannadasan T. Preparation of biodiesel from sunflower oil by transesterification. Int J Biosci Biochem Bioinformatics. 2012;2(6):441-445. Preparation of biodiesel from sunflower oil by transesterification

- Fahey J. Moringa oleifera: A review of the medical evidence for its nutritional, therapeutic, and prophylactic properties. Part 1. In: Trees, Life, and the Environment. 2005. doi:10.1201/9781420039078.ch12 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rashid U, Anwar F, Moser BR, Knothe G. Moringa oleifera oil: a possible source of biodiesel. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99(17):8175-8179. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2008.03.066 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Olushola SM. Extraction and Characterization of Moringa oleifera Seed Oil. Res Rev J Food Dairy Technol. 2013;1(1):22-27. Extraction and Characterization of Moringa oleifera Seed Oil

- Mohammed A, Lai OM, Muhammad K, Long K, Mohd Ghazali H. Moringa oleifera, potentially a new source of oleic acid-type oil for Malaysia. J Oil Palm Res. 2003;3:137-140. Moringa oleifera, potentially a new source of oleic acid-type oil for Malaysia

- Decentralized oil production in Zimbabwe. Spore. 1995;60:CTA, Wageningen, The Netherlands. Decentralized Oil Production in Zimbabwe

- Kant P, Wu S. The extraordinary collapse of Jatropha as a global biofuel. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45(17):7114-7115. doi:10.1021/es201943v PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Acharya SK, Mishra AK, Rath M, Nayak C. Performance analysis of karanja and kusum oils as alternative biodiesel fuel in diesel engine. Int J Agric Biol Eng. 2011;4(2):23. doi:10.3965/j.issn.1934-6344.2011.02.023-028 Google Scholar

- Philomina NS, Rao JV. Micropropagation of Sapindus mukorossi Gaertn. Indian J Exp Biol. 2000;38(6):621-624. Micropropagation of Sapindus mukorossi Gaertn

- Chhetri AB, Tango MS, Budge SM, Watts KC, Islam MR. Non-edible plant oils as new sources for biodiesel production. Int J Mol Sci. 2008;9(2):169-180. doi:10.3390/ijms9020169 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Atabani AE, Silitonga AS, Ong HC, et al. Non-edible vegetable oils: A critical evaluation of oil extraction, fatty acid compositions, biodiesel production, characteristics, engine performance, and emissions production. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2013;18(C):211-245. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2012.10.013 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Yu XW, Sha C, Guo YL, Xiao R, Xu Y. High-level expression and characterization of a chimeric lipase from Rhizopus oryzae for biodiesel production. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2013;6(1):29. doi:10.1186/1754-6834-6-29

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Zhuang D, Jiang D, Liu L, et al. Assessment of bioenergy potential on marginal land in China. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2011;15:1050-1056. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2010.11.041 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wang Y, Cheng MH, Ko CH, et al. Lipase catalyzed transesterification of tung and palm oil for biodiesel. 2011. doi:10.3384/ecp1105787 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sarin A. Biodiesel Production and Properties. Cambridge, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2012. Biodiesel Production and Properties

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

None

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Magaji Amayindi

Department of Pure and Industrial Chemistry

Bayero University Kano, Nigeria

Email: magajiamayindi@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Jimoh Yakubu Onimisi

Department of Biochemistry

Federal University Wukari, Nigeria

Joel Yakubu

Department of Community Health

Taraba State College of Health Technology, Nigeria

Rubiyamisumma Dorcas Kaduna

Department of Science Education

Adamawa State University, Nigeria

Authors Contributions

Magaji Amayindi contributed as the author. Jimoh Yakubu Onimisi, Joel Yakubu, and Rubiyamisumma Dorcas Kaduna served as reviewers.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest Statement

Not reported

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Magaji A, Jimoh YO, Joel Y, Rubiyamisumma DK. Synthesis of Biodiesel Through Transesterification of Non-Palatable Oil and Its Physicochemical Parameters Determining Biodiesel Quality. medtigo J Pharmacol. 2025;2(1):e3061216. doi:10.63096/medtigo3061216 Crossref