Author Affiliations

Abstract

Beta-blockers are commonly prescribed for several conditions, including hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias, coronary artery disease, and heart failure. Their physiologic effects also contribute to the often-devastating results when taken in excess. Beta-blocker overdosing can lead to bradycardia, hypotension, and ultimately cardiogenic shock. In this case report, we review an 18-year-old female who ingested multiple drugs, including a significant amount of metoprolol, in a suicide attempt. Multiple interventions were initiated in the Emergency Department to combat the medications’ negative cardiovascular and neurologic effects. Despite these interventions, the patient had a seizure followed by multiple cardiac arrest events, leading to anoxic brain injury and eventually the declaration of brain death. The case underscores the challenges in managing beta-blocker overdose and highlights the need for vigilance in recognizing and treating its potentially life-threatening complications.

Keywords

Beta-blocker, Cardiogenic shock, Metoprolol, Seizure, Propranolol, Hypertension.

Introduction

Metoprolol is a selective beta1-adrenergic receptor inhibitor, also known as a β-blocker. It competitively blocks the beta1 receptor with minimal effects on beta2 receptors at oral doses less than 100 mg in adults and is therefore considered cardio-selective.[1, 2] Due to negative inotropic and chronotropic effects, it reduces cardiac output; the degree of this drop varies with drug dose and concentration. Metoprolol has a few labeled indications, including chronic stable angina, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, chronic hypertension, and myocardial infarction. Other off-label uses include atrial fibrillation/flutter, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, migraine prevention, supraventricular tachycardia, thyrotoxicosis, and ventricular arrhythmias.[1] Additional uses of beta-blockers include glaucoma, migraine prophylaxis, and anxiety.[2]

While beta-blocker overdoses account for a small number of poisonings in the United States, the 2022 Annual Report from America’s Poison Centers revealed that beta blockers were ranked 7th among drug categories with the largest number of fatalities at 4.29%.[3] Patients presenting with beta-blocker toxicity will often demonstrate bradycardia associated with hypotension as the first clinical manifestation.[4] Beta-blockers with high lipid solubility, like propranolol, can easily cross the blood-brain barrier compared to less lipophilic beta-blockers like atenolol, which do not.[5] Metoprolol is a moderately lipophilic beta-blocker and has a low incidence of CNS findings if administered at clinically correct doses; however, in the case of overdose, the risk of these side effects is increased.[5, 6] This case reviews the clinical course and management of an 18-year-old female with polysubstance ingestion, including a clinically significant amount of metoprolol, and the literature surrounding metoprolol-induced seizures.

Case Presentation

An 18-year-old, 145 kg female was brought to the emergency department by her mother after the intentional ingestion of metoprolol extended-release, calcitriol, pantoprazole, and ranolazine in an attempt to commit suicide two hours prior to arrival. It was estimated that the patient took more than 60 tablets of metoprolol and only a few tablets of the other medications. The patient had a long history of depression, which she states has been worsening over the last few months. She had one prior suicide attempt via overdose the year prior. She was not receiving any psychiatric care or medications at the time of the presentation. The medications involved in the overdose belonged to the patient’s grandmother, kept in a locked box, which the patient took without the grandmother’s knowledge.

On arrival, the patient’s vitals were as follows: Temperature of 36.8°C, heart rate of 68 beats per minute (bpm), blood pressure (BP) of 81/45 mmHg, pulse ox of 96%, fingerstick glucose of 98. On physical exam, the patient had a depressed affect but was otherwise awake, alert, and oriented x4. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 15 and neurological exam were grossly intact. The remaining exam was unremarkable.

Case Management

The initial management included stabilization of the patient, including two large-bore intravenous (IV) lines, a fluid bolus, cardiac monitoring, glucagon drip, electrocardiogram (ECG), and consultation with poison control. The ECG showed no significant abnormalities, rhythm was normal sinus, QTc was 429, PR interval was 180, and QRS segment was not wide. Poison control stated that the patient was outside the window for activated charcoal. After IV placement, glucagon 5 mg IV was administered, followed by a glucagon drip. During initial resuscitation, she began developing more profound bradycardia, for which 0.5 mg of IV atropine was administered. The drug screen was negative for acetaminophen, salicylates, and alcohol. The patient’s remaining lab work was unremarkable. The patient showed a good response to the initial therapy with glucagon and atropine; however, two hours after arrival (approximately four hours after ingestion), she became increasingly somnolent, bradycardic (40 bpm), and persistently hypotensive with a systolic BP in the 80’s mmHg. Several minutes before this decline, the patient lost all IV access, which was difficult to obtain initially and required the placement of two ultrasound-guided large-bore peripheral IVs. After securing venous access, an additional dose of atropine 0.5 mg IV and Narcan 0.4 mg IV were given, and the patient’s systolic blood pressure improved to 101 mmHg, with the HR improving to 70 bpm. After this, the patient remained hemodynamically stable on a glucagon drip and was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further care.

Throughout the next day in the ICU, the patient continued to remain hemodynamically stable, with no additional episodes of hypotension or bradycardia. Approximately 24 hours after ingestion, the patient was witnessed with seizure-like activity, which deteriorated into cardiac arrest. Return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) was achieved after 9 minutes of ACLS. The patient was intubated during cardiac arrest. A loading dose of levetiracetam 1500 mg IV was started, followed by 1000 mg twice daily for seizure control. Prior to this hospitalization, the patient had no history of seizure disorder. Initial Computed Tomography (CT) of the brain following her seizure showed no acute intracranial abnormalities.

Despite anticonvulsive therapy, on the patient’s 3rd day of admission, she had an additional seizure and three more episodes of cardiac arrest over the span of 45 minutes. Each of the preceding rhythms before the arrests was sinus bradycardia. ROSC was achieved after several minutes each time. CTA of the chest was obtained and was negative for pulmonary embolism but showed extensive bilateral pulmonary infiltrate. She developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) for which she was started on epoprostenol. At this point, the patient remained critically ill, requiring multiple vasopressors (norepinephrine, epinephrine, and vasopressin) to maintain a mean arterial pressure (MAP) >65.

Despite these interventions, the patient’s illness and complications had resulted in anoxic brain injury. On the morning of the patient’s 5th day of admission, she was pronounced brain dead and the following day was taken for organ procurement.

Discussion

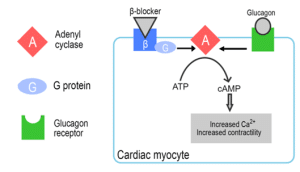

Beta-blockers act upon receptors to reduce intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), resulting in negative inotropic and chronotropic effects. For that reason, initial management of beta-blocker overdose primarily aims to restore cardiac output. Treatment with catecholamines (i.e., norepinephrine, epinephrine, and vasopressin) has all been used with variable success.[7] Historically, glucagon has been described as the first-line therapeutic to counter beta receptor blockade. At high dosages, glucagon has been demonstrated to increase heart rate, blood pressure, and cardiac contractility. It is thought that glucagon acts on the cardiac myocytes, bypassing the beta receptor, to increase intracellular cAMP.[4] For this reason, most clinicians use glucagon to address hypotension and bradycardia induced by high doses of beta blockers. However, the precise dosage of glucagon required for toxicological emergencies lacks evidence from controlled research trials.[8] In this case, the patient was quickly started on a glucagon drip and showed an initial improvement in cardiac output.

Figure 1: Effects of beta blockers and glucagon on Cardiac myocyte

Although the medical interventions improved the patient’s cardiac stability, she was still at risk for CNS complications such as seizures, respiratory depression, and coma. Historically, literature on “seizures related to beta-blocker use” mentions only highly lipophilic beta-blockers like propranolol.[10] and their ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, leading to the potential of seizure. Based on our literature review, there have been very few articles describing a similar relationship in moderately lipophilic beta-blockers such as metoprolol. As mentioned previously, metoprolol is more likely to cross the blood-brain barrier at elevated dosages, such as in the setting of an intentional overdose. One article reported CNS complications linked to metoprolol administration in elderly populations. It highlights the increased vulnerability of elderly patients to CNS manifestations associated with metoprolol usage. Reported symptoms included headaches, confusion, sleep disturbances, and visual hallucinations.[11] However, there was no mention of similar risk in younger populations, such as the patient in this case, who was 18 years old. One article describes the successful treatment of metoprolol overdose where, in addition to treatment with glucagon, catecholamines, and atropine, diazepam was given prophylactically to prevent the onset of seizures.[12] Seizures in the setting of beta-blocker poisoning should be aborted with benzodiazepines as the first-line agents, but more research is needed to justify the usage prophylactically.[13] Literature has also suggested the use of hemodialysis in beta-blocker poisonings to increase drug clearance; however, due to metoprolol’s poor water solubility, it is only slightly dialyzable. Some publications report that metoprolol may be dialyzed with an achievable clearance of 80-120 ml/min, but this still only accounts for <10% of the total body clearance.[14]

Conclusion

Beta-blocker toxicity remains a prominent contributor to mortality among poisonings in the US. Managing beta-blocker toxicity poses significant challenges with high mortality rates despite prompt intervention. Further investigations into the neurological effects of metoprolol overdose are warranted to improve understanding and therapeutic strategies for future patients.

References

- Morris J, Awosika AO, Dunham A. Metoprolol. Online edition. StatPearls Publishing; 2024 PubMed

- Farzam K, Jan A. Beta Blockers. StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 PubMed

- Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Beuhler MC, et al. 2022 Annual Report of the National Poison Data System® (NPDS) from America’s Poison Centers®: 40th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2023;61(10):717-939. doi:10.1080/15563650.2023.2268981

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Khalid M.M., Galuska M.A., Hamilton R.J. Beta-Blocker Toxicity. 2024 ed. (Internet). Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed 2023 Jul 28 Beta-Blocker Toxicity

- Cove-Smith JR, Kirk CA. CNS-related side effects with metoprolol and atenolol. Eur J Clin Pharmacol.1985;28(S1):69-72. doi:10.1007/BF00544858 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Liu X, Lou X, Cheng X, Meng Y. Impact of metoprolol treatment on mental status of chronic heart failure patients with neuropsychiatric disorders. Drug Des Devel Ther.2017;11:305-312. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S128974

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Barrueto F. Beta blocker poisoning. In: UpToDate, Connor RF, ed. Wolters Kluwer. March 8, 2024 Beta blocker poisoning

- Petersen KM, Bøgevig S, Riis T, et al. High-Dose Glucagon Has Hemodynamic Effects Regardless of Cardiac Beta-Adrenoceptor Blockade: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(21):e016828. doi:10.1161/JAHA.120.016828 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Morris CH, Baker J. Glucagon. 2024 Jan. (Internet). Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Glucagon

- Reith DM, Dawson AH, Epid D, Whyte IM, Buckley NA, Sayer GP. Relative toxicity of beta blockers in overdose. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol.1996;34(3):273-278. doi:10.3109/15563659609045633 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Shah R, Babar A, Patel A, Dortonne R, Jordan J. Metoprolol-Associated Central Nervous System Complications. Cureus. 2020;12(5):e8236. doi:10.7759/cureus.8236 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bala P, Ali A, Rahman KA, Islam N, Khan MH. A case of massive metoprolol overdose successfully managed. Bangladesh Heart J.2020;35(1):71-73. doi:10.3329/bhj.v35i1.49365 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ocak M, Çetinkaya H, Kesim H. A Case of High Dose Metoprolol Poisoning; Case Report and Literature Review: Beta Blocker Poisoning Treatment. İJCMBS.2021;1(1):12-5. doi: 54492/ijcmbs.v1i1.6 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bouchard J, Shepherd G, Hoffman R, et al. Extracorporeal treatment for poisoning to beta-adrenergic antagonists: systematic review and recommendations from the EXTRIP workgroup. Crit Care.2021;25(1):1-12. doi:10.1186/s13613-021-00899-2 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

Not reported

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Hannah Sodergren

Department of Emergency Medicine

PGY-3, HCA Florida Orange Park Hospital

2001 Kingsley Ave, Orange Park, FL 32073

Email: hannah.sodergren@hcahealthcare.com

Co-Authors:

Justin H. Le, BS

Department of Osteopathic Medicine

OMS-III, Student Doctor

Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine, Carolinas Campus

350 Howard St, Spartanburg, SC 29303

(864) 327-9800

Email: jle@carolinas.vcom.edu

Shilpa Amin, MD

Department of Emergency medicine

Emergency Medicine Attending, HCA Florida Orange Park Hospital

2001 Kingsley Ave, Orange Park, FL 32073

Email: shilpa.amin@teamhealth.com

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Informed Consent

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest Statement

None

Guarantor

Not applicable

DOI

Cite this Article

Sodergren H, Le JH, Amin S. Seizures in the Setting of Metoprolol Overdose. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(3):e3062252. doi:10.63096/medtigo3062252 Crossref