Author Affiliations

Abstract

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) is rapidly improving and leads to metabolic disease and severe complications. This study assessed the safety and efficacy of antithrombotics in patients with diabetes, and their complications and coexisting atrial fibrillation (AF) risk. It compared the effectiveness and safety of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) to conventional oral antithrombotic (OAT) medications (warfarin and aspirin) concerning anti-glycemic agents. This is a cross-sectional study. Primary data was collected through a questionnaire when interviewing the patients, followed by a systemic review using clinical scores such as the congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes mellitus, prior stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or thromboembolism, vascular disease, age, sex category (CHA2DS2-VASc), and Hypertension, Abnormal Renal/Liver Function, Stroke, Bleeding History or Predisposition, Labile International normalized ratio (INR), Elderly, Drugs/Alcohol Concomitantly (HAS-BLED). Secondary data collection involved a thorough review of existing research and literature. Significant interactions were observed between antithrombotic and anti-glycemic agents. Warfarin combined with sulfonylurea or metformin posed moderate to severe hypoglycemic risks. Insulin has a weak interaction with warfarin, reflecting a low hypoglycemia risk. Aspirin showed a moderate risk only with sulfonylurea. Warfarin and aspirin are associated with a higher risk of bleeding with sulfonylurea, but a minimal risk with metformin and insulin. OATs have a 60.8% risk of hypoglycemia and a 55.1% risk of bleeding. DOAC showed strong correlations in reducing stroke and hypoglycemia (Pearson correlation coefficient [PCC] is 0.969), and a strong correlation in reducing bleeding (PCC is 0.769). These findings suggest that DOACs may offer a safer alternative to OATs in patients with diabetes and AF.

Keywords

Diabetes mellitus, Oral Antithrombotic, Direct oral anticoagulants, Warfarin, Aspirin, Metformin.

Introduction

DM, which is also called the epidemic of the century, is a chronic disorder characterized by elevated blood sugar levels due to insulin insufficiency or insulin resistance. It can cause serious complications that increase morbidity and mortality if left untreated, including cardiovascular diseases, peripheral neuropathy, retinopathy, and nephropathy [1,2,3].

To diagnose DM, a combination of medical history and laboratory testing is required. Important factors in the history like lifestyle habits, and symptoms of DM such as polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, fatigue, weight loss, blurred vision, poor healing of sores or wounds, and paresthesia in the extremities in addition to laboratory tests used to diagnose DM include the Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG) test, Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT), and hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) [2,3].

Type I DM (TIDM) and Type II DM (TIIDM) are the two main types of diabetes. TIDM happens when the cells in the pancreas that produce insulin are destroyed, causing an absolute insulin deficiency. In contrast, TIIDM develops due to a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. The exact cause of TIDM is unclear, but it is believed to involve genetic and environmental triggers. It’s important to note that TIDM is not caused by lifestyle choices. However, TIIDM is more closely associated with a sedentary lifestyle and an unbalanced diet in addition to genetic predisposition. Other risk factors include family history, age, hypertension, and dyslipidemia [2,3].

DM is a major global health concern, with a rising prevalence worldwide, particularly in Jordan. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the global prevalence of diabetes among adults aged 20-79 years is estimated at 10.5% [4,5], while in Jordan it stands at 15.4% [6]. Preventing diabetes globally requires raising awareness, promoting healthy lifestyles, and implementing effective prevention strategies.

Diabetes imposes a significant risk for macrovascular and/or microvascular complications, including cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction [MI], and stroke due to the increased risk of atherosclerosis [1,3]. Experimental and clinical trials provided strong evidence of the relation between DM and AF, which is the most common type of heart arrhythmia worldwide. Patients with diabetes have a 15% chance of developing AF, accounting for 30% of all cases [7,8]. In addition, without proper management, hyperglycemia can lead to microvascular complications including retinopathy (eye damage) & and nephropathy (kidney damage) [2,3].

DM treatment involves early screening, lifestyle modifications, and various medications. Metformin is considered the first-line treatment for Type II diabetes. It works by inhibiting hepatic gluconeogenesis, increasing peripheral insulin sensitivity, and decreasing intestinal glucose absorption. Insulin is another class of medications used in both Type I and Type II diabetes by binding to insulin receptors. When binding occurs, it triggers the dimerization of receptors and autophosphorylation, which in turn initiates downstream signaling cascades. Phosphorylated signaling molecules activate Glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) translocation to the plasma membrane, which facilitates glucose uptake. These can have side effects such as hypoglycemia, nausea, and vitamin B12 deficiency. Other options include sulfonylureas, which improve insulin production and insulin sensitivity [2,3].

Antithrombotic medications are used to prevent blood clots and consist of anticoagulants like warfarin and antiplatelet agents [9,10]. Warfarin functions by limiting the liver’s production of clotting factors II (prothrombin), VII, IX, and X, thus reducing the formation of clots [11]. As warfarin lowers the body’s vitamin K levels, it can result in reduced clotting factor production, leading to bleeding [12]. Other common side effects of warfarin include increased INR and interactions with other medications and foods [13]. To mitigate these risks, administration of vitamin K intravenously or orally and ceasing warfarin can be effective [14]. Another type of antithrombotic medication that is widely used is aspirin, which is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory and antiplatelet drug used for pain relief and prevention of blood clots [15,16]. It works by blocking the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme that produces prostaglandins, which promote platelet clotting and other functions [17]. Common side effects include gastrointestinal complaints, while severe side effects may lead to gastrointestinal and intracranial bleeding [18,19,20]. Treatment for overdose includes gastric lavage or activated charcoal [21].

DOACs are another type of antithrombotic medication that prevents and treats blood clots without requiring frequent monitoring of blood levels. They work by inhibiting direct thrombin and Factor Xa, making them more convenient than traditional anticoagulants like warfarin. Common uses include AF, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. DOACs can cause bleeding and gastrointestinal symptoms, but are generally easier to manage than warfarin. Four main types of DOACs exist: dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban, each targeting different clotting factors. Proper dosage and monitoring are essential to avoid complications [10,11,12].

This study provides valuable insights into the efficacy and safety of antithrombotic medications (warfarin and aspirin) on patients with DM. The results will contribute to our understanding of diabetes management and highlight areas where further research or interventions may be necessary to improve patient outcomes.

Methodology

Data Source and Data Selection

In this research, the impact of OAT (warfarin and aspirin) on patients with TIIDM in Jordan was investigated, which helped to explore the safety and efficacy of OAT on patients with TIIDM, including the study of related complications and coexisting heart diseases such as AF. Also, the effectiveness and safety of using DOACs were investigated compared to traditional OAT (warfarin and aspirin). The type of data needed was quantitative and qualitative data, collected through both primary and secondary means. For primary collection, a questionnaire was conducted, and data were collected when interviewing the patients. This was followed by a systematic review of the findings and the use of clinical scores like the CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores to check the findings. For the secondary data collection, a thorough review of the existing research and literature was conducted. The available information will be carefully analyzed to ensure that our findings are well-informed and accurate.

Furthermore, both data collection methods will be used to maximize the reliability and accuracy of the findings, as using only one method won’t provide enough data for this type of research. The questionnaire, which was designed to collect data from patients with DM on antithrombotic medication, aimed to gather data from patients by asking them to answer the questions in the form during the interview. During the interview, the following questions were asked about the patient: age, type of DM, regularity of diabetes medication intake and medication name, history of cardiovascular events (especially AF), previous incidents of stroke, MI or systemic embolism, any complications arising from DM (macrovascular or microvascular), regular intake of antithrombotic and the name of the antithrombotic (particularly warfarin), complications experienced after taking antithrombotics (such as bleeding from any part of the body or hypoglycemic symptoms indicating hypoglycemia), the patient’s risk of cardiovascular disease (whether it is decreasing or increasing), previous use of DOACs and any symptoms experienced after taking them, alcohol consumption, intake of certain drugs (such as statins, thiazides, or antipsychotics), the duration of antithrombotic medication intake, and whether the patient has any coagulation disorder. The interviews with the patients were scheduled in primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare facilities. Before the interviews, consent and a signature were obtained from the patient on a consent form to ensure confidentiality. Moreover, the purpose of this research was clearly explained, and it was emphasized that any data collected would be used solely for research purposes. Additionally, patients’ personal information would not be collected, nor would any information provided be disclosed.

After completion of data collection, the data will be cleaned regarding specific parameters of inclusion and exclusion criteria to define the study population and enhance validity. The inclusion criteria included patients with TIIDM, any patient with TIIDM despite having hypertension or cardiovascular disease before the study, any age group with TIIDM, the patient must take at least one DM medication, take the medication regularly, and be on antithrombotic medication and take the medication regularly. The exclusion criteria included any patient with TIDM, a patient who doesn’t take any DM medication, doesn’t take any antithrombotic medication, or doesn’t take medications regularly, any personal history of coagulation disorder, and if the patient drinks alcohol or takes any of these drug agents (statin, thiazides, antipsychotics).

Data quality and data assessment

DM:

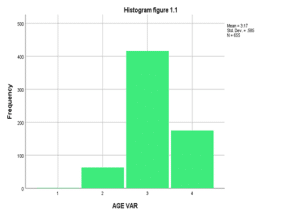

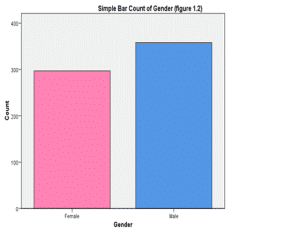

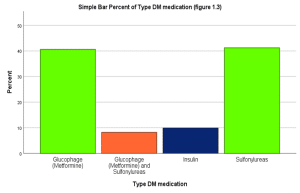

After cleaning the data, the total responses were 803, 655 met the inclusion criteria, and 148 met the exclusion criteria. Then, the data were imported into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) program to analyze the data collected. The age groups were divided into four subgroups based on age: 40-50 (group 1), 50-60 (group 2), 60-70 (group 3), and above 70 (group 4). After analyzing the age groups, the mean age was found to be 3.17 (60-70), with a standard deviation (SD) of 0.584 and a median of 3 (60-70). The percentage distribution of age subgroups: 40-50 (0.2%), 50-60 (9.6%), 60-70 (63.5%), over 70 (26.7%). In addition to that, the percentage of males and females was found to be males (54.7%) and females (45.3%). The coexisting DM with AF and other heart diseases was found to be 62.3%. On the other hand, 37.7% didn’t suffer from anything. Regarding strokes, MI, and cerebral vascular accident (CVA) in patients with DM, the percentage of patients who suffered from strokes, MI, and CVAs was found to be (99.4% suffered from strokes, MI, CVA, and 0.6% didn’t suffer from anything). Furthermore, the complications that patients with DM had suffered from were studied, and these complications were divided into 8 categories, these categories with their percentage as found to be: poor vision (16.9%), kidney function (9.7%), kidney failure (7.6%), diabetic foot (15.3%), poor vision and diabetic foot (0.2%), poor vision, diabetic foot, and decreased kidney function (0.2%), poor vision and decreased kidney function (43.8%), poor vision and kidney failure (6.3%). Patients who take DM medications regularly are divided into four categories based on their anti-glycemic agent intake; these categories with their percentages as found to be: glucophage (Metformin) alone (40.6%), sulfonylureas alone (41.2%), glucophage (Metformin), and sulfonylureas (8.3%), insulin alone (9.9%) (Table 1.1).

| Count | Column N % | ||

| Age | >70 | 175 | 26.7% |

| 40-50 | 1 | 0.2% | |

| 50-60 | 63 | 9.6% | |

| 60-70 | 416 | 63.5% | |

| Gender | Female | 297 | 45.3% |

| Male | 358 | 54.7% | |

| Type DM medication | Glucophage (Metformin) | 266 | 40.6% |

| Glucophage (Metformin), Sulfonylureas (DiaBeta, Glynase, or Micronase (glyburide or glibenclamide), Amaryl (glimepiride), Diabinese (chlorpropamide), Glucotrol (glipizide), Tolinase (tolazamide) | 54 | 8.3% | |

| Insulin | 65 | 9.9% | |

| Sulfonylureas (DiaBeta, Glynase, or Micronase (glyburide, glibenclamide),

Amaryl (glimepiride), Diabinese (chlorpropamide), Glucotrol (glipizide),Tolinase (tolazamide) |

270 | 41.2% | |

| AF and Heart disease | No | 247 | 37.7% |

| Yes | 408 | 62.3% | |

| Strokes, MI, CVA | No | 4 | 0.6% |

| Yes | 651 | 99.4% | |

| Complications of DM | Diabetic foot | 100 | 15.3% |

| Poor vision | 111 | 16.9% | |

| Poor vision, Diabetic foot | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Poor vision, Diabetic foot, decreased kidney function | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Poor vision, decreased kidney function | 287 | 43.8% | |

| Poor vision, Kidney failure | 41 | 6.3% | |

| Decreased kidney function | 64 | 9.8% | |

| Kidney failure | 50 | 7.6% | |

Table 1.1: Analysis of responses based on age, gender, DM medication, AF, and heart disease, Strokes, MI, CVA, and complications.

OAT:

There are two main types of OAT that patients mainly use: aspirin and warfarin. It was found that 50.8% used warfarin as an antithrombotic agent and 49.2% of patients used aspirin. In general, the percentage of patients who suffered from complications like hypoglycemia after taking these medications was 60.8%, while 39.2% didn’t suffer from any hypoglycemia symptoms. Moreover, the percentage of patients who suffered from bleeding after taking OAT was 55.1%. However, 44.9% didn’t suffer from bleeding. Both OAT have effectively decreased the incidence of strokes, MI, and CVA by 99.7% (Table 1.2). In our research, the duration during which patients have taken oral antithrombotics was studied, and it was found that patients who took OAT for less than one year, 0.2%, from one to three years, 0.9%, and more than three years, 98.9% (Table 1.3).

| Count | Column N % | ||

| Type of OAT | Aspirin | 322 | 49.2% |

| Warfarin | 333 | 50.8% | |

| Complications-OAT (Warfarin and Aspirin) | No | 257 | 39.2% |

| Yes | 398 | 60.8% | |

| Hypoglycemia-OAT (Warfarin and Aspirin) | No | 257 | 39.2% |

| Yes | 398 | 60.8% | |

| Bleeding-OAT (Warfarin and Aspirin) | No | 294 | 44.9% |

| Yes | 361 | 55.1% | |

| Stroke-OAT ratio (Warfarin and Aspirin) | Decreased | 653 | 99.7% |

| Doesn’t have a stroke | 2 | 0.3% | |

Table 1.2: Type of OAT

| Frequency | % | Valid % | Cumulative % | ||

| Valid | From one to three years | 6 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Less than one year | 1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.1 | |

| More than three years | 648 | 98.9 | 98.9 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 655 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

Table 1.3: Duration of OAT (Warfarin and Aspirin)

DOACs:

New oral anticoagulants are used as an alternative to traditional OAT (warfarin and aspirin). In our study, the efficacy of these anticoagulants in comparison to traditional OAT was studied, and it was found that 405 patients used this type of DOAC during their lifetime management at one point after using OATs. It was found that these agents are safer and more effective in decreasing hypoglycemia symptoms when compared to traditional OAT, as all patients who took this type admitted to decreasing hypoglycemia symptoms by 100%. Also, DOAC is better than OAC in decreasing bleeding and strokes, MI, and CVA. Regarding the bleeding, it was found that patients who used DOAC decreased bleeding compared to OAC by 100%, and for the strokes, MI, and CVA, all patients who used this type admitted that DOAC is better than OAC in reducing these events by 100%. On the other hand, 205 patients didn’t use DOACs before (Table 1.4).

| Count | Column N % | ||

| DOAC taking | Yes | 405 | 100.0% |

| DOAC is better than OAT (Warfarin and Aspirin) in reducing hypoglycemia | Yes | 405 | 100.0% |

| DOAC is better than OAT (Warfarin and Aspirin) in reducing stroke | Yes | 405 | 100.0% |

| DOAC is better than OAT (Warfarin and Aspirin) in reducing bleeding | Didn’t bleed before | 137 | 33.8% |

| Yes | 268 | 66.2% | |

Table 1.4: Type of direct oral anticoagulants

Results

Safety measures of antithrombotic medications:

The study was conducted on a sample of 803 patients with diabetes in Jordan. Of these, 148 patients were excluded based on exclusion criteria, and most of the patients were within the age group 60-70 years old, with most patients being males, accounting for 54.7% of the total sample. All included patients were on diabetes medication, with metformin and sulfonylurea being the most used, with usage rates of 40.6% and 41.6%, respectively (Figure 1.1).

Hypoglycemia:

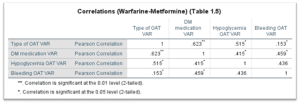

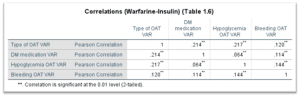

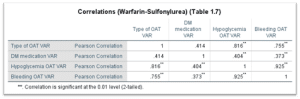

The first area of investigation was the correlation between the safety of diabetes medication and antithrombotic medications with the incidence of hypoglycemia, specifically aspirin and warfarin, along with metformin, insulin, and sulfonylurea. Based on the analysis of Tables 1.5, 1.6, and 1.7, the following findings can be concluded. A strong correlation was found between the use of warfarin and metformin in causing hypoglycemia (PCC is 0.515), which suggests that when these two medications are used together, it increases the risk of experiencing low blood sugar. Furthermore, a poor correlation was found between warfarin and insulin in causing hypoglycemia (PCC is 0.207), which implies that the use of warfarin alongside insulin doesn’t significantly contribute to hypoglycemia. Interestingly, the worst and strongest correlation was observed between warfarin and sulfonylurea regarding hypoglycemia (PCC is 0.816). These findings highlight the importance of closely monitoring patients who are prescribed both warfarin and metformin, and taking caution when prescribing warfarin alongside sulfonylurea due to the high risk of experiencing hypoglycemia.

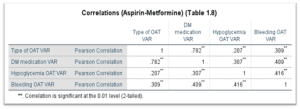

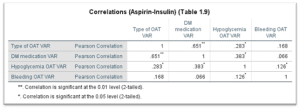

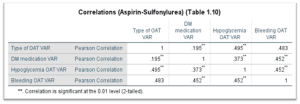

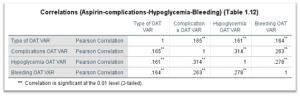

Upon reviewing tables 1.8, 1.9, and 1.10, it was discovered that there is a poor correlation between aspirin and insulin in causing hypoglycemia (PCC is 0.283), this means that the use of aspirin doesn’t significantly increase the risk of hypoglycemia when used in combination with insulin, a similar result was found between combination of aspirin and metformin (PCC is 0.207). A correlation between aspirin and sulfonylurea in causing hypoglycemia (PCC is 0.495) was detected; this means that there is a potential risk when using this combination. Overall, these findings suggest that while there may be a correlation between aspirin and certain diabetes medications in causing hypoglycemia, it is not significant enough to warrant major concern. Further studies may be needed to understand the full interaction between those medications.

Bleeding:

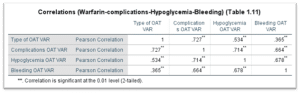

From another perspective, the focus of the study was to investigate the safety of utilizing antithrombotics (aspirin and warfarin) with diabetes medications (insulin, metformin, and sulfonylurea) in terms of their risk of causing bleeding. After reviewing tables 1.5, 1.6, and 1.7, the findings revealed a poor correlation between warfarin and metformin in causing bleeding (PCC is 0.153). Similarly, a weak correlation was observed between warfarin and insulin in causing bleeding (PCC is 0.120). However, a strong correlation was found between warfarin and sulfonylurea in causing bleeding (PCC is 0.755). Caution should be taken when prescribing warfarin and sulfonylurea to patients with diabetes to minimize bleeding risk.

Furthermore, the research studies the safety of using aspirin with certain diabetes medications, and after inspecting tables 1.8, 1.9, and 1.10, there is a lack of significant correlation between the use of aspirin and insulin in causing bleeding (PCC is 0.168). Also, the risk of bleeding is minimal when using aspirin in combination with metformin (PCC is 0.309). However, caution should be taken when considering the combination of aspirin and sulfonylurea, as there is evidence of a correlation between these two medications and an increased risk of bleeding (PCC is 0.483).

Efficacy (cardiovascular outcome):

The research findings indicate that oral antithrombotics have proven to be highly effective in reducing the risk of cardiovascular diseases. A staggering 99.7% of patients reported a significant decrease in the risk of stroke, CVA, and MI after incorporating oral antithrombotic therapy into their treatment regimen. OAT has a crucial role to play in preventing these life-threatening conditions and underscores their importance in managing cardiovascular health.

Complications Related to DM:

Regarding DM complications, as mentioned in the methodology, it was found that the two most common complications were poor vision combined with decreased kidney function or poor vision alone, with percentages of 43.8% and 16.9%, respectively. These results can be attributed to poor control of diabetes medications and a significant percentage of hypertension patients in Jordan.

Complications related to antithrombotics:

According to the data collected, the antithrombotics used among patients with diabetes are aspirin, warfarin, and DOACs. Out of the individuals who used aspirin or warfarin, 60.8% experienced serious complications, including bleeding and hypoglycemia. In detail, after comparing aspirin and warfarin and reviewing tables 1.11 and 1.12, it became clearer that warfarin had stronger correlations regarding complications than aspirin, with values of PCC of 0.727 and 0.165, respectively.

DOAC:

Efficacy and safety:

Prescribing DOAC has been more prevalent than traditional antithrombotics these days. DOAC is a medication that is known for its safety and effectiveness. Based on data analysis, all 404 participants who used DOAC reported that it is better than traditional medications in reducing strokes and hypoglycemia symptoms. Additionally, 66.2% of the participants said that DOAC had reduced bleeding, while the remaining 33.8% did not experience any bleeding.

Outcomes in relation to traditional antithrombotics:

After reviewing Table 1.13, it is not surprising that DOACs have surpassed traditional antithrombotics in reducing the incidence of complications. According to data analysis, DOAC showed strong and equal correlations in reducing stroke events and hypoglycemia symptoms, with a PCC of 0.969. In addition, there was a strong correlation, indicated by a PCC of 0.769, in reducing bleeding.

| Complication | S-OAT VAR | Hypoglycemia-OAT VAR | Bleeding-OAT VAR | Stroke-OAT ratio VAR | DOAC is better than OAT | Reducing Hypoglycemia VAR |

| S-OAT VAR | 1 | 0.844** | 0.673** | 0.932** | 0.969** | 0.769** |

| Hypoglycemia-OAT VAR | 0.844** | 1 | 0.713** | 0.923** | 0.979** | 0.879** |

| Bleeding-OAT VAR | 0.673** | 0.713** | 1 | 0.686** | 0.751 | 0.690** |

| Stroke-OAT ratio VAR | 0.932** | 0.923** | 0.686** | 1 | 0.972** | 0.672** |

| DOAC is better than OAT | 0.969** | 0.970** | 0.751** | 0.972** | 1 | 0.913** |

| Reducing Hypoglycemia VAR | 0.769** | 0.879** | 0.690** | 0.672** | 0.913** | 1 |

Table 1.13: Pearson Correlations (DOAC-OAT (Warfarin and Aspirin))

Note: ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Discussion

Despite the valuable findings that the research revealed, further evaluation is needed to understand these results. It was found that multiple factors affect how males and females may respond to antithrombotics and anti-glycemic medications, including biological, physiological, and genetic factors. It has been noted in our results that males are affected more than females, with a percentage of 54.7% and 45.3%, respectively. (Figure 1.2) However, these differences can be related to differences in body weight and composition, which can affect medication distribution and metabolism, leading to differences in drug effectiveness and side effects [22].

There are biological factors that can cause differences between men and women in how drugs are metabolized in their bodies. As we know, women have a low body weight but high fat content, unlike men, and that will cause differences between them in the volume of distribution and clearance. Drugs that are water soluble, like warfarin, will have low volume distribution and high clearance in women, unlike men, which means a shorter half-life [23]. Moreover, female hormones, especially estrogen, fluctuate during the menstrual cycle and can affect how the body processes medications by affecting enzymes involved in drug metabolism [24]. The activity of cytochrome P450, which plays a major role in drug metabolism, can vary between males and females, and differences in its activity can affect how the body processes and eliminates medications [25]. Furthermore, genetic factors can affect how an individual responds to medication. These differences may vary between genders, leading to varying outcomes between males and females in the metabolism and clearance [26,27].

Other factors like diet, physical activity, and lifestyle factors can cause differences in how drugs are metabolized in the body between females and males [28,29]. Patients with DM will suffer from complications like retinopathy and nephropathy [30]. Regarding results, the percentage of both complications was 43.8%. Several factors can cause these complications. Firstly, the long duration of uncontrolled high blood sugar can damage microvasculature, leading to diabetic retinopathy and nephropathy [31]. Secondly, poorly controlled diabetes over a long period can lead to the accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in the blood vessels. That can damage the vessel’s function, causing inflammation and affecting surrounding tissue. Moreover, the AGEs can promote the formation of atherosclerotic plaques, which can narrow and block blood vessels [32,33]. Finally, controlled blood pressure and cholesterol levels are important in DM patients as elevated levels can accelerate complications and develop other complications like cardiovascular diseases. Furthermore, unhealthy lifestyle choices, such as poor diet, lack of physical activity, smoking, and excessive alcohol consumption, can accelerate complications in patients with DM [34].

Regarding DM medications, Patients use metformin and sulfonylurea due to their effectiveness, safety, and affordability [35,36] (Figure 1.3). However, warfarin is a major agent when talking about traditional oral antithrombotics and is associated with more complications when compared with aspirin, which our result showed PCCs of 0.727 and 0.165, respectively. This is likely caused by the high potency of this antithrombotic, which significantly reduces the blood’s ability to clot and therefore causes bleeding. It works by inhibiting the production of several clotting factors in the liver, including factor II (prothrombin), VII, IX, and X [37]. Aspirin, on the other hand, is an antiplatelet agent that primarily prevents platelets from sticking together and forming clots [38].

Moreover, multiple factors can affect dosing between warfarin and aspirin, such as diet, medication interactions, and individual metabolism, making it difficult to achieve and maintain correct anticoagulation levels [39]. Also, consuming vitamin K-rich foods can impact warfarin, so users should monitor their intake of vitamin K. Furthermore, warfarin can interact with many medications and some herbal supplements, leading to fluctuations in anticoagulation levels [40]. In contrast, aspirin may increase the risk of bleeding to some extent, but is usually linked with a lower risk of major bleeding events as compared to warfarin [41].

Finally, DOACs offer several advantages over OATs. Firstly, DOACs have a more predictable antithrombotic effect, which means they don’t require regular blood monitoring or dose adjustments like warfarin, making treatment simpler. Additionally, DOACs have fewer interactions with other medications and foods compared to warfarin. Warfarin, on the other hand, is highly sensitive to vitamin K intake and interacts with large numbers of drugs, which can complicate treatment. DOACs do not have the same dietary restrictions as warfarin, which requires patients to be careful about vitamin K intake from foods, making it easier for them to follow a normal diet. Lastly, DOACs have shorter half-lives; thus, their antithrombotic effects fade sooner after withdrawal [42,43,44,45].

Generally, sulfonylureas are well known for their protein-binding drug interactions. It is well known that first-generation sulfonylureas are considered to have a substantial risk of causing this interaction, possibly due to the displacement of the protein binding mechanism, affecting the attachment of the protein at its destination, and therefore increasing the plasma concentration of sulfonylurea [46]. It has been found that the concomitant use of warfarin with sulfonylurea in older age groups (mean age: 73.3) who had other co-morbidities, showed a higher risk of hypoglycemia by 16.7 per 1000 person- year on the contrary of using sulfonylurea alone (mean age: 61.0) by 13.8 per 1000 person-year [47,48]. We did not study using sulfonylurea alone, as it was an exclusion criterion. However, our results showed that patients taking warfarin with sulfonylurea have a higher risk of bleeding and hypoglycemia compared to those taking aspirin with sulfonylurea. The concurrent use of aspirin with sulfonylurea or other anti-diabetic medications used for the prevention of cardiovascular events increased the risk of hypoglycemia [49]. The risk increased due to a decrease in renal excretion of sulfonylurea, and/or displacement from albumin [50].

Per Nam et al, it has been noted that warfarin and metformin (RR: 1.73) showed a statistically higher risk of causing hypoglycemia in comparison with warfarin and sulfonylurea (RR: 1.47) [51]. The analysis of responses from our study group showed that the use of warfarin with sulfonylurea resulted in a PCC of 0.816, exhibiting the highest ability to cause hypoglycemia, followed by warfarin and metformin (PCC 0.515), then aspirin and sulfonylurea (PCC 0.495). These were the top three combinations that increased hypoglycemia risk in the group. Meanwhile, any combination with insulin had the lowest impact. Research concluded that the use of DOACs had the lowest risk of hypoglycemia among the anti-thrombotic agents. Moreover, the risk of serious hypoglycemia in DOACs and sulfonylurea combined was diminished [52], showed no association between the latter drugs [47], or lowered the risk in comparison with warfarin [53].

Warfarin has a higher risk of bleeding [54] when compared with apixaban (DOACs) used in patients with diabetes, it was associated with a lower risk of major bleeding events [55], and a lower risk of systemic embolism and stroke [56]. As well as better results when managing the severity and intensity of bleeding than warfarin [57]. This proves the higher efficacy and safety of DOAC in Type II DM in preventing strokes for patients with AF and non-valvular AF. When comparing the efficacy of aspirin to DOACs, there is no adequate data on the topic [58,59,60].

This study provides a valuable understanding of the relationship between OAT and patients with DM in Jordan. However, there are several limitations. Firstly, the sample size we used was relatively small, although statistically adequate, as we only took data from 803 patients out of a total of 866,500 cases of diabetes in adults. This may limit the extent to which our results can be applied to a wider population. Secondly, the data collection process depended on self-reported information, which introduces the potential for recall bias and social desirability bias. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of our study only allowed for the identification of associations between variables, preventing us from establishing causation. Despite our valuable results, the T value couldn’t be calculated and depended on the PCC to compare the results, so the findings are non-significant and only descriptive data without showing causation. Future research should consider addressing these limitations through larger, more diverse samples, longitudinal designs, and more rigorous data collection methods. Furthermore, the findings of our study may not be generalizable to other regions due to unique cultural and demographic factors specific to the geographic area where the study was conducted.

There were several challenges in finding patients who were willing to participate in the interview, such as concerns about the privacy of sensitive information or personal health information being studied. Also, patients may have difficulty finding a suitable interview time due to busy schedules, medical appointments, treatments, or work commitments. Finally, to overcome these challenges and increase the number of patients recruited, researchers focused on building trust, addressing privacy concerns, providing clear and concise information, and offering emotional support or other benefits for participation. Moreover, increasing the use of DOAC as an alternative to warfarin and aspirin should be a priority in Jordanian healthcare centers, as only a small group of patients currently use DOAC.

Conclusion

This cross-sectional study found that the use of DOACs in patients with diabetes managed to reduce symptoms of hypoglycemia, bleeding, and Cardiovascular events (stroke, SE, MI & CVA) with 100% improvement in symptoms, contrary to traditional oral anti-thrombotic (Table 3). Warfarin and sulfonylurea exhibited the highest incidence of causing severe hypoglycemia (PCC 0.816) and bleeding (PCC 0.755), supporting that warfarin has the highest outcome on risk factors. Warfarin and metformin outcomes on hypoglycemia and bleeding (PCC 0.515 and 0.153), and aspirin-sulfonylurea (PCC 0.495, 0.483), respectively. Further research on the strong side effects of oral antithrombotics with anti-diabetics is encouraged. Moreover, increasing the use of DOAC as an alternative to warfarin and aspirin should be a priority in Jordanian healthcare centers, as only a small group of patients currently use DOAC.

References

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Diabetes mellitus: A guide to diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. National Institutes of Health; 2023. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK)

- Kadota Y, Ogawa S, Kadowaki T. Diabetes mellitus: From molecular mechanisms to clinical perspectives. J Diabetes Investig. 2023;14(1):2-13. Diabetes mellitus: From molecular mechanism to pathophysiology and pharmacology – ScienceDirect

- Goyal R, Singhal M, Jialal I. Type 2 diabetes. NCBI Bookshelf; 2023. PubMed | Google scholar

- World Health Organization. Diabetes. World Health Organization; 2023. Diabetes

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas IDF Diabetes Atlas Reports | IDF Diabetes Atlas

- Al-Ameri M, Hamdan MA. Diabetes in Jordan: Prevalence, trend, awareness, and control. 2023:1-7. Iproceedings – Diabetes in Jordan: Prevalence, Trend, Awareness and Control

- Bohne LJ, Johnson D, Rose RA, Wilton SB, Gillis AM. The Association Between Diabetes Mellitus and Atrial Fibrillation: Clinical and Mechanistic Insights. Front Physiol. 2019 Feb 26;10:135. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00135. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Leopoulou M, Theofilis P, Kordalis A, et al. Diabetes mellitus and atrial fibrillation—from pathophysiology to treatment. World J Diabetes. 2023;14(5):512-527. doi:10.4239/wjd.v14.i5.512. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. Antithrombotic agents. In: National Institutes of Health; 2020. Antithrombotic Agents – LiverTox – NCBI Bookshelf

- Ajjan RA, Kietsiriroje N, Badimon L, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in diabetes: which, when, and for how long? Eur Heart J. 2021;42(23):2235-2259. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab128. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ansell J, Hirsh J, Jacobson NA, Johnston M. American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based practice guidelines for the management of antithrombotic therapy: 2012 update. 2013;143(6):e264S-e488S. PubMed

- You JJ, Singer DE, Howard PA, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e531S–e575S. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- National Institutes of Health. Warfarin. In: National Institutes of Health; 2022. Warfarin – LiverTox – NCBI Bookshelf

- Hirsh J, Guyatt G, Albers GW, Harrington R, Schünemann HJ. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):110S–112S. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Patrono C, Bhatt DL. Antiplatelet therapy for cardiovascular events. 2013;128(18):2363-2383. PubMed

- Derry S, Moore RA. Single dose oral aspirin for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Apr 18;2012(4):CD002067. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002067.pub2. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sear JW. Pharmacology. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91(5):764–765. Crossref

- Gaiani F, De’Angelis N, Kayali S, et al. Clinical approach to the patient with acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Acta Biomed. 2018;89(8-S):12–19. Clinical approach to the patient with acute gastrointestinal bleeding | Acta Biomedica Atenei Parmensis

- Huang WY, Saver JL, Wu YL, Lin CJ, Lee M, Ovbiagele B. Frequency of Intracranial Hemorrhage With Low-Dose Aspirin in Individuals Without Symptomatic Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Aug 1;76(8):906-914. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1120. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Paez Espinosa EV, Murad JP, Khasawneh FT. Aspirin: pharmacology and clinical applications. 2012;2012:173124. doi: 10.1155/2012/173124 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Danel V, Henry JA, Glucksman E. Activated charcoal, emesis, and gastric lavage in aspirin overdose. Br Med J. 1988;296(6635):1507-1510. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Principles of gender-specific medicine. ScienceDirect. Principles of Gender-Specific Medicine | ScienceDirect

- Charness ME, Karaszewski SLR. Sex and gender differences in pharmacology. 3rd ed. Springer; 2018. Sex and Gender Differences in Pharmacology | SpringerLink

- Kamimori GH, Joubert A, Otterstetter R, Santaromana M, Eddington ND. The effect of the menstrual cycle on the pharmacokinetics of caffeine in normal, healthy eumenorrheic females. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;55(6):445–449. Crossref | Google Scholar

- Soldin OP, Mattison DR. Sex differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;48(3):143–157. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rane A, Lindh JD. Pharmacogenetics of anticoagulants. Hum Genomics Proteomics. 2010;2010:754919. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Florez JC. Genetic susceptibility to type 2 diabetes and implications for therapy. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009 Jul 1;3(4):690-6. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300413 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bushra R, Aslam N, Khan AY. Food-drug interactions. Oman Med J. 2011;26(2):77–83.

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Lenz TL. The effects of high physical activity on pharmacokinetic drug interactions. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2011;7(3):257–266. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- American Diabetes Association. American Diabetes Association releases 2023 standards of care in diabetes to guide prevention, diagnosis, and treatment for people living with diabetes. American Diabetes Association Releases 2023 Standards of Care in Diabetes to Guide Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment for People Living with Diabetes | American Diabetes Association

- Yang J, Liu Z. Mechanistic Pathogenesis of Endothelial Dysfunction in Diabetic Nephropathy and Retinopathy. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:816400. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Singh VP, Bali A, Singh N, Jaggi AS. Advanced glycation end products and diabetic complications. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;18(1):1–14. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Khalid M, Petroianu G, Adem A. Advanced Glycation End Products and Diabetes Mellitus: Mechanisms and Perspectives. 2022;12(4):542. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(Suppl 1):S1-S157. American Diabetes Association Releases 2023 Standards of Care in Diabetes to Guide Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment for People Living with Diabetes | American Diabetes Association

- Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, et al. International Diabetes Federation consensus glucose control recommendations 2017. Diabetes Care. 2017;41(Suppl 1):S13-S76. PubMed

- Chiasson JL, Joslin ME, Hanney BL, Karrison TJ. Metformin vs sulfonylureas in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(11):1962-1973.

- Reiffel JA. Novel oral anticoagulants. Am J Med. 2014;127(4):e16–e17. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Jourdi G, Godier A, Lordkipanidze M, Marquis-Gravel G, Gaussem P. Antiplatelet Therapy for Atherothrombotic Disease in 2022-From Population to Patient-Centered Approaches. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:805525. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Taylor F, Cohen H, Ebrahim S. Systematic review of long term anticoagulation or antiplatelet treatment in patients with non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation. Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE): Quality-assessed Reviews. Google Scholar

- Nutescu EA, Shapiro NL, Ibrahim S, West P. Warfarin and its interactions with foods, herbs, and other dietary supplements. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2006;5(3):433–451. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ambrosi P, Daumas A, Villani P, Giorgi R. Meta-analysis of major bleeding events on aspirin versus vitamin K antagonists in randomized trials. Int J Cardiol. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Owens RE, Kabra R, Oliphant CS. Direct oral anticoagulant use in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation with valvular heart disease: a systematic review. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40(6):407–412. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(12):1139–1151. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):883–891. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society. Focused update of the 2014 guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. 2019;140(2):e125-e151. PubMed | Crossref

- Triplitt C. Drug interactions of medications commonly used in diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 2006;19(4):202-211. Crossref | Google Scholar

- Alwafi H, Wong ICK, Naser AY, et al. Concurrent use of oral anticoagulants and sulfonylureas in individuals with type 2 diabetes and risk of hypoglycemia: A UK population-based cohort study. Front Med.

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Romley JA, Gong C, Jena AB, et al. Association between use of warfarin with common sulfonylureas and serious hypoglycemic events: Retrospective cohort analysis. BMJ. 2015. Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sianni A, Matsoukis I, Paraskevas P, et al. The combination of aspirin with antidiabetic drugs increases the number of hypoglycaemic events in patients with type 2 diabetes. Eur J Intern Med. 2013;24:e100. Crossref | Google Scholar

- Amiel SA, Dixon T, Mann R, Jameson K. Hypoglycaemia in Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2008;25(3):245–254. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Nam YH, Brensinger CM, Bilker WB, et al. Serious hypoglycemia and use of warfarin in combination with sulfonylureas or metformin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;105(1):210–218. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Dimakos J, Cui Y, Platt RW, et al. Concomitant use of sulfonylureas and warfarin and the risk of severe hypoglycemia: Population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(10):e131–e133 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Huang HK, Liu PP, Lin SM, et al. Risk of serious hypoglycaemia in patients with atrial fibrillation and diabetes concurrently taking antidiabetic drugs and oral anticoagulants: a nationwide cohort study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2023;9(5):427-434. doi:10.1093/ehjcvp/pvab059. PubMed

- Bang OY, On YK, Lee M, et al. The risk of stroke/systemic embolism and major bleeding in Asian patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation treated with non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants compared to warfarin: Results from a real-world data analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0242922. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0242922

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Lip GYH, Keshishian AV, Kang AL, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral anticoagulants in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(5):929-943. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.11.023 PubMed

- Huang L, Tan Y, Pan Y. Systematic review of efficacy of direct oral anticoagulants and vitamin K antagonists in left ventricular thrombus. ESC Heart Fail. 2022;9(5):3519-3532. doi:10.1002/ehf2.13860. PubMed

- Ballestri S, Romagnoli E, Arioli D, et al. Risk and management of bleeding complications with direct oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolism: a narrative review. Adv Ther. 2023;40(1):41-66. doi:10.1007/s12325-022-02118-6. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gulluoglu RF, Souverein PC, van den Ham HA, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin in UK patients with atrial fibrillation and type 2 diabetes: A retrospective cohort study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2021;30(10):1293-1320. doi:10.1002/pds.5267. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Acanfora D, Ciccone MM, Carlomagno V, et al. A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation patients with diabetes using a risk index. J Clin Med. 2021;10(13):2924. doi:10.3390/jcm10132924. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cao B, Yao X, Zhang L, et al. Efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with diabetes and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: Meta-analysis of observational studies. Cardiovasc Ther. 2021;39(5):e12849. doi:10.1111/1755-5922.12849. Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

Not reported

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Saed Bani Amer

Department of Medicine

Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

Email: saedbamer0000@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Khaled Al-Sawalmeh

Department of Pathology

Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

Yara Al-Slati

Department of Medicine

Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

Lena Almemeh

Department of Medicine

Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

Bayan Amoorah

Department of Medicine

Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

Mohammad Melhem

Department of Physical Education

Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

Rowan Alzoubi

Department of Medicine

Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

Abdulaziz Alanazi

Department of Medicine

Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set by the Human Research Ethics Council at Yarmouk University and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Human Research Ethics Council at Yarmouk University, approval Number IRB/2023/513. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study. Participants were provided with detailed information about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits, and were assured of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Not reported

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Saed Bani A, Khaled A-S, Yara A-S, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Conventional Antithrombotics versus Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Diabetic Patients: A Jordanian-Based Cross-Sectional Study. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(3):e3062245. doi:10.63096/medtigo3062245 Crossref