Author Affiliations

Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has plagued millions of human beings across the world in a short time interval and forced the world to experience extraordinary economic and life losses. Consequently, it is compulsory to find operational cures against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), because it is the biological cause of COVID-19. Synthetic medicines, such as hydroxychloroquine, have gained significant attention. Though the effectiveness of this drug is still under examination, and moreover, certain severe consequences are a source of distress. This underlines the urgency for treatment alternatives, which can be achieved in cooperation with efficiency and safety. Until now, there are no specifically recognized drugs to fight this virus, and the procedure for new drug development is prolonged. Most encouraging candidates, who emerged as prospective frontrunners, were abandoned later while still in the phase of clinical examinations. With no convincing therapeutics in the prospect, natural products are in wide use randomly as anti-viral remedies and immune promoters. For centuries, it has been well-known that most marine natural products have effective anti-viral properties against SARS-CoV-2. It has been revealed that natural products show inhibitory activities in the treatment of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and SARS-CoV infections.

Keywords

Severe acute respiratory syndrome, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, Coronavirus disease, Clinical examination, Anti-viral properties.

Introduction

A virus such as the coronavirus could be spread from one host to another.[1] Coronaviruses have been in existence right from time past as microscopic pathogens or flora in cats, bats, and camels [2]. The first acknowledged infectious epidemic and public health disaster linked with coronaviruses was recognized in 2003 as SARS, as reported.[3] Thus, Coronavirus-19 is currently known as SARS-CoV-2, it is an ribonucleic acid (RNA) that is single-stranded beta-corona virus which causes pathologically severe condition.[4] The original virus, SARS-CoV-2, belongs to the family Coronaviridae. The family comprises SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV, two zoonotic viruses that arose in 2003 and 2012, respectively.[4]

Though extremely active vaccines targeting SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins have been accepted for emergency usage by numerous stringent supervisory authorities, mutations in the spike protein might permit the virus to be spread more efficiently and, in the worst-case situation, evade the immune reaction triggered by vaccines.[5-7] Coronaviruses have displayed an extraordinary capacity to jump the species barrier, and additional coronaviruses may travel from animal reservoirs to humans in the near future. Meanwhile, for those reasons, it is crucial to recognize broad-spectrum antivirals that prevent diverse coronaviruses and aid in treating the illnesses triggered by these viruses.

SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 have a comparable natural antiquity of contamination; both enter the upper respiratory region and infect the epithelial cells lining the respiratory tract. They go into target cells by forming a bond to the surface spike proteins of human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, the key viral receptor, present on the surface of target cells. Hence, antiviral agents that aim SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 access have the possible potential to prevent/treat these contaminations (infection).[8]

These qualities can be subjugated in the strategy of lead (Pb) compounds with a theoretically broad spectrum of inhibition. Mostly, an appropriate substrate can be transformed into a good inhibitor through parts replacement of the substrate structure that binds directly to the active position of the protease, reversibly or permanently, having a chemical warhead targeting the catalytic mechanism. Peptide deactivators were premeditated by ascribing a chemical warhead, such as aldehyde, Michael acceptors, and ketones, etc., to a peptide that impersonates the natural substrate.[9] The deactivators act via a double-step mechanism, whereby they first of all bind and form a non-covalent complex with an enzyme, for example, the warhead is organized close to the catalytic residue. Afterward, the nucleophilic attack transpires at the cysteine, resulting in covalent bond formation. Certain peptidomimetic derivatives comprise Michael acceptors serving as warheads, which are a significant class of cysteine protease deactivators. The cysteine remainder undergoes 1,4-addition to the inhibitor at the Michael acceptor warhead cluster, and the successive addition of hydrogen to the α-carbanion results in the irretrievable inhibition of the target enzyme.[9] It ought to be reflected that the bulk of fatal cases are defenseless people with comorbidities, for example, diabetes or heart disease, and immunosuppression disease. The key dispute all around the world is the great human-to-human spread that has resulted in the spread of epidemics in numerous countries.[10]

The aim of this work is to carry out a virtual selection against the SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) binding site by means of the collection of Aquatic Natural Products. Many marine natural products have been discovered to possess several biochemical activities; isolated peptides from algal polysaccharides and fish have been stated to have anticoagulant and anti-cancer inhibitory activities. Aquatic bacteria and fish oils comprise a substantial aggregate of omega-3 fatty acids, while seaweeds and crayfishes (crustaceans) have effective antioxidants, including phenolic and carotenoid compounds.[11] Archaeologically, natural products played a significant part in drug detection, principally for tumors and several other contagious illnesses.[12,13] However, also in other medical areas, including circulatory diseases such as statins and multiple sclerosis, such as fingolimod.[14,15]

Transmission pathway:

The first incident of a COVID-19 case was recognized in a seafood market in China (Wuhan); however, other cases were not connected with it. Transmission from one human to another followed later, and individuals operated as hosts and transporters of the virus.[1] The demonstration of the contamination comprised arthralgia, dry cough, fever, tiredness, and anosmia (loss of taste and smell).

Symptomatic persons were kept in quarantine and isolation for a certain period. Viral spread was related to respiratory droplets from coughing.[16] Asymptomatic personalities can also transfer the contagion. Assuming that they are not isolated, they may transfer up to 80% of the infection compared to symptomatic people, who are identified and isolated on time.[17] It is evident that the spread of the virus is more predominant in intensive care units, compared with all-purpose wards, possibly due to the large number of devices generating aerosols. This is also applicable to COVID-19 patients admitted or hospitalized in such sections amongst non-COVID-19 patients. Such a contrast is not valid in COVID-19 wards, where all the patients are infected. Furthermore, the virus can be transmitted on computer mice, floors, trash bins, door handles, and individuals can be infected via a handshake with an infected person or surfaces.[18]

Aerosols could be initiated from dental actions and numerous medical operations and processes, such as bronchoscopy, endotracheal intubation, exposed suctioning, nebulized cure administration, manual aeration afore intubation, rotating the patient to a susceptible position, detaching the patient away from the air duct, noninvasive helpful pressure airing, cardiopulmonary resuscitation and tracheostomy. Also, aerosols may be formed by a dewdrop oozing during a usual dialogue or an infected subject sneezing and coughing.[19] These discoveries have also been validated by much research. In Tongji Hospital in Wuhan (China), several healthcare personnel were infected while they were treating infected individuals.[20] Particles having a size less than 100 μm, airborne spread, are predominantly suspected of conveying SARS-CoV-2.[21]

From the report (data) obtained from China COVID-19 Control Agencies, it has been established that the virus can remain viable for about 3 to 7 days, and the period from contamination to symptoms takes 12.5 days. The data disclosed that the virus doubles every 7 days.[22]

Natural product:

In the past, natural products have been and are extensively used everywhere in the world.[23-25] Currently, nearly 200,000 natural products are extracted. Huang’s study found that an alkaloid (berbamine) was found to hinder genome duplication and minimize communicable virus production via Vero E6 cells.[26] Terpenoids also have inherent potency to be advanced and used as a cure for COVID-19.[27]

The use of nanoparticles from natural products for COVID-19 management:

Layqah et al.[28] reported investigative and healing procedures centered on nanotechnology, such as nutritive nanotechnology, have remained uneasy for scientists since the beginning of the COVID-19 epidemic or the expansion of extremely delicate antigens for COVID-19 recognition examinations or assessment. Uniting the COVID-19 anti-S protein antibody to a grapheme piece as a delicate area, avoiding antigenic cross reactivity with MERS-CoV, and productively discovering the virus in clinical trials with great thoughtfulness and no sample prior treatment.[29,30]

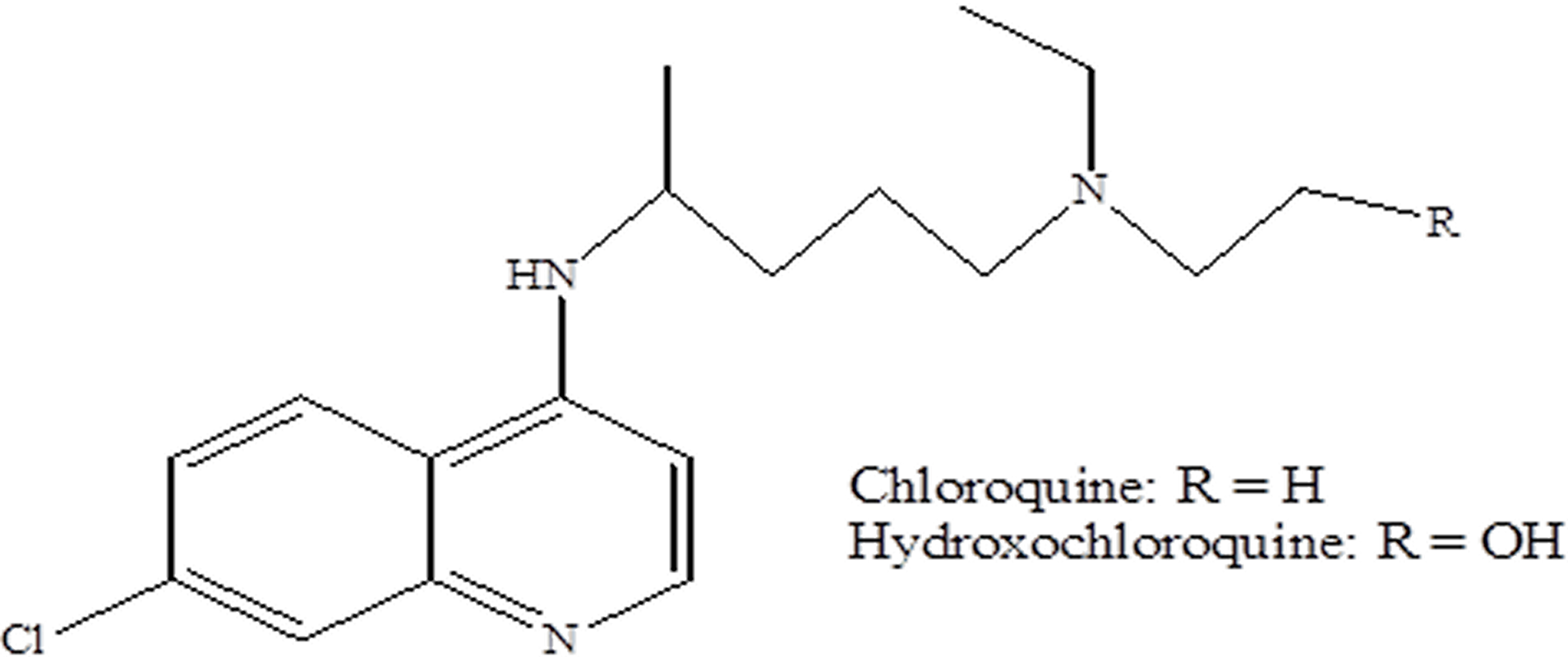

The most frequently used therapeutic approaches for treating COVID-19 with moderate to severe symptoms in infected patients have functioned well, including those formerly used safely, herbal treatment medicines, even though they were not initially envisioned as antivirals.[31] Some of the most effective and promising herbal therapy medicines decrease viral load and duration of hospital stay, disease severity, and death, and some have been verified in clinical tests.[32-35] Chloroquine is a distinctive medicine that is obtained from the original long-term use of natural products.[36,37] It has been used to treat malaria after the recognition and decontamination of active constituents, structural depiction, and comprehension of the mechanism or mode of drug action, as well as the derivative alteration of the drugs. During the COVID-19 epidemic, the use of chloroquine to manage COVID-19 was introduced by the State Congress of China. An in-vitro introductory study was carried out; some test carried out in patients displayed reduced regaining periods.[38,39] The Nutrition Drug Organization approved hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine for temporary use in March. The key mode of action is that the flow into the lung cells can be triggered by transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS-2).[31,40]

Figure 1: Chemical structures of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine

Constituent parts with diverse materials and structures appear in dissimilar ways, such as lipid-centered nanoparticles, inorganic nanoparticles, and polymer nanoparticles.[41] Additionally, the benefits of nanoparticles in conveying large drug particles also have the merit of being modified with ease and functionalized.[42] The mode of action of nanoparticles to exercise an anti-viral activity is recognized via numerous pathways, such as direct or indirect virus inactivation, virus penetration, virus reproduction, and virus activity in host cells, depending on the functioning ability and nature of the nanoparticles that are used.[43] The nanoparticles can either block these mechanisms chemically or physically, or modify the configuration of capsid proteins, thus decreasing the viral capacity.[44]

Marine natural products against COVID-19:

Marine-sourced natural products are being utilized as potent therapeutic remedies in recent times. Marine micro-algae from the family of Phaeophyta and phyla Rhodophyta were investigated, and several bioactive composites such as phycocyanin, vitamins, lutein, phenolics, polysaccharides, and several others displayed numerous fundamental pharmacological activities.[45]

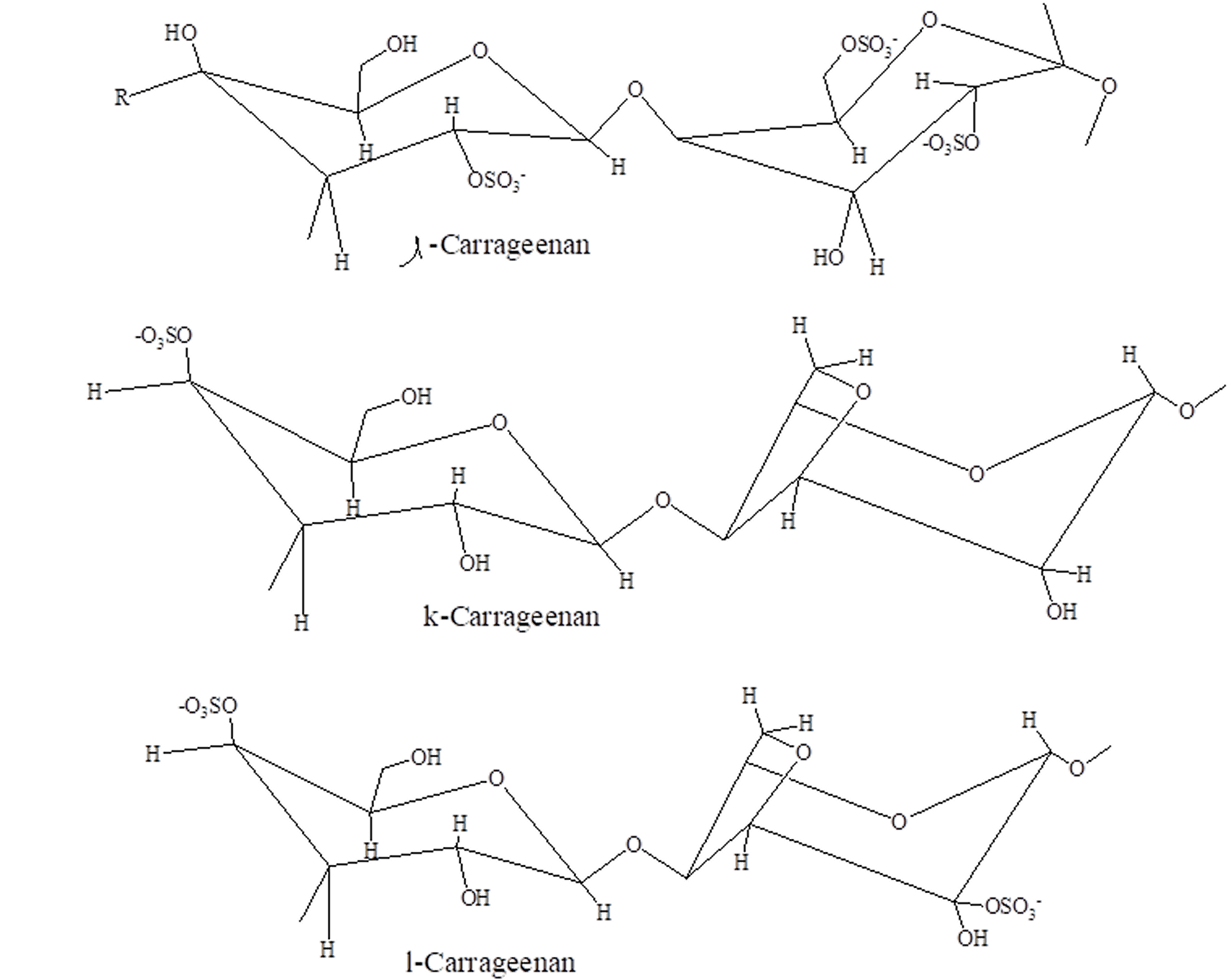

Carrageenan and griffithsin (Figure 1), sulfur-containing polysaccharides, can target an extensive variety of enclosed viruses.[46] Essentially, griffithsin has, over time, been shown to exhibit a wide range of in vitro actions against the family of coronaviridae and in vivo action against SARS-CoV-1 in a rat simulation carried out via intranasal intake.[47,48] The activity of sulfur-containing polysaccharides against severe acute respiratory coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2).[49,50]

Figure 2: Different forms of carrageenan

Griffithsin is a six (6) carbohydrate binding spot, also a homo-dimeric lectin with a high affinity for abundant mannose arrays. Mannose arrays are commonly seen in viral spikes of significant pathogens such as hepatitis corona virus (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), ebola virus, herpes simplex virus (HSV) and coronaviridae family members,[51] The capability to wedge HIV in-vitro, at Pico-molar amount, makes Griffithsin to be among the most effective molecules deterring HIV reproduction.[52] Even though EC50 values are greater for coronaviruses compared to HIV, Griffithsin is powerful enough to make this naturally occurring agent a favorable candidate to combat the present SARS-CoV-2 epidemic. Moreover, regarding the efficacy of medicine, Griffithsin is lowly immunogenic, and numerous studies in animal simulations have revealed its outstanding safety profile.[53] Carrageenans are polysaccharides (carbohydrates) isolated from red seaweed; their expansive antiviral range comprises viruses like rhinoviruses, HSV, and coronaviruses. The antiviral inhibition is well recognized against the Hepatitis virus and is perhaps the most powerful anti-HPV agent testified in the writings.[54, 55]

Several preclinical and scientific investigations have revealed its tremendous well-being (safety) profile after lung and vaginal paths of administration.[56,57] Furthermore, as stated by the Food and Drug Administration.[58] Carrageenan is commonly acknowledged as safe by the Food and Drug Management and has regularly been used as a nourishment additive. In this, we additionally discover the possible antiviral discrimination of Griffithsin, sulfated as well as non-sulfated polysaccharides, and mixtures of the two against SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2.

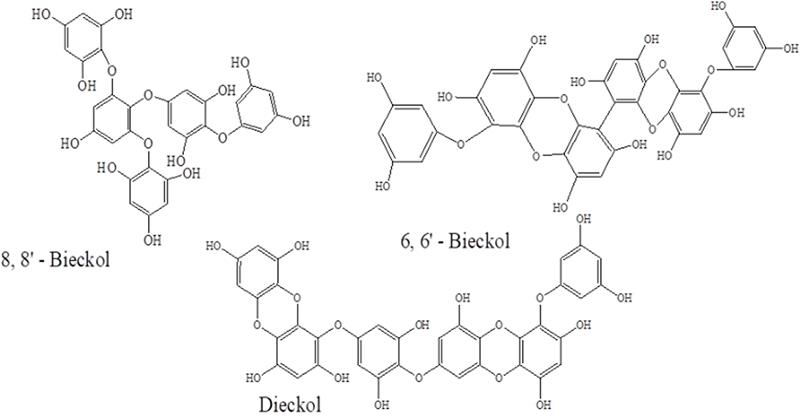

The ultimate and effective inhibitors of the SARS-CoV-2 Main protease (Mpro) are principally characterized by a 1,3,5-trihydroxybenzene, which belongs to a class of molecules termed phloro-tannins, oligomers of phloroglucinol; it was isolated from the brown alga (Sargassum spinuligerum).[58,59] Even though the majority of these phlorotannins were recognized in S. spinuligerum, other classes of Sargassum may perhaps also comprise an enormous number of phloro-tannins, comprising phlorethols, fucophlorethols, and fuhalols.[60] Chinese herbal medicines largely contain Sargassum, which is obtained from the alga family. It has been found that 6, 6’-Bieckol, 8, 8’-Bieckol, and Diekol compounds, as displayed in Figure 2 below, are very active inhibitors; they belong to the phloro-tannins family, which was obtained from Ecklonia cava (brown algae). The second is palatable seaweed, which in the past has been documented as an endowed spring of bioactive derivatives, predominantly phlorotannins. Phlorotannins display numerous useful biological activities namely, anti-cancer, antioxidant, anti-diabetic, antihypertensive, anti- HIV, matrix metalloproteinase enzyme retardation, radio-defending, anti-allergic and hyaluronidase enzyme reserve.[61-66]

Figure 3: Chemical structures of three phlorotannins

Park et al.[68] highlighted that significantly, Dieckol has previously been stated as one of the greatest and powerful SARS-CoV-1 Main protease (Mpro) phloro-tannin inhibitors with an IC50 equal to 2.7 µM. Docking investigations stated that collaborations between amino acid residues and dieckol in the active site of Main protease are primarily established by an H-bond linkage with a premeditated bond energy (−11.76 kcal/mol).

Hirata et al.[69] reported the antioxidant efficacy and anti-viral properties of phycocyanobilin, which is classified under tetra-pyrrole chromophores obtained from a particular category of marine cyanobacteria. Phycocyanobilins proved to have a great binding attraction for both severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 and main protease through in silico molecular docking studies.[70] The in vitro examination of fucoidans obtained from Sargassum henslowianum (brown microalgae) and sulfated giant sugar (polysaccharides) on HSV presented effective inhibitory activities.[71] Also, fucoidans obtained from the macro-algae Saccharina japonica exhibit key antiviral properties against SARS-CoV-2. However, it was established that fucoidans could be administered alongside other antiviral compounds to stimulate persuasive anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity.[72]

Vijayaraj et al.[73] reported that Esculetin ethyl-ester obtained from marine loofa Axinella corrugate exhibited resilient interaction against SARS-CoV-2 protease, which could serve as a good remedy to fight against COVID-19. Recently, in Silico investigation assisted in recognizing possible lead compounds for medicine improvement against the COVID-19 epidemic. Khan et al.[67] In their molecular dynamic examination, they discovered powerful anti-SARS-CoV-2 MPRO agents such as fostularin 3, 15-alphamethoxypuupehenol, 1 hexadecoxypropane-1,2-diol, puupehedione, and palmitoleic acid obtained from marine bases, which can be exploited for hindering the pathological progression in the host. Discovery of powerful natural compounds from aquatic bases remains an issue due to the rare accessibility, tough collection, and scarcity of marine animals. A few decades ago, the pursuit of effective natural compounds from oceanic bases that can display a plethora of actions was ongoing and is conveying positive outcomes. So, it can deduce these verdicts to discover a probable antidote from the naturally existing marine creatures. Polyphenols such as kaempferol, herbacetin, and rhoifolin are natural products possessing great antiviral activity; they are structurally similar.[74-76]

Figure 4: Chemical Structures of 1-Hexadecoxylpropane-1,2-diol, Palmitoleic Acid, Herbacetin, and Rhoifolin

The phenyl and chromen-4-one segments of the kaempferol molecule are accountable for its binding effectively with the SARS-CoV MPRO. Meanwhile, herbacetin has an extra 8-hydroxyl group, whose outcomes resulted in a durable bond to the SARS-CoV MPRO. Rhoifolin has a huge a-L-rhamnopyranosyl, b-D-glucopyranoside and chromen-4-one segment, which clearly defines its robust binding effect to the SARS-CoV MPRO as the large group fits into the receptacles of the protein with hydrogen bonding, Park et al.[68]

Conclusion

There is a strategy to source a COVID-19 management remedy that can be swiftly manufactured and simply disseminated worldwide. Marine natural products could offer a solution to this predicament, because they are generally toxic and are used in the therapeutic industry for their unique bioactivity, including antiviral. The comparison between COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-1 paves the way for the improvement of new medicines as well as vaccines. Carrageenan and griffithsin possess outstanding potential to be used as a remedy for managing COVID-19. Essentially, griffithsin has, in the past, been shown to exhibit an extensive range of in vitro interactions against the family of coronaviridae and in vivo action against SARS-CoV-1 in a rat simulation carried out via intranasal administration, O’Keefe et al.[48] The activity of sulfur-enclosing polysaccharides against SARS-CoV-2, Morokutti-Kurz et al.[49] and Moulaei et al.[50] The majority of the current investigation is theoretical or yet to present analytical authentication; a long pathway is still ahead in terms of biochemical analysis and enhanced abstraction and invention.

References

- Riou J, Althaus CL. Pattern of early human-to-human transmission of Wuhan 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), December 2019 to January 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(4):2000058. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.4.2000058

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Nagahawatta DP, Liyanage NM, Jayawardena TU, et al. Role of marine natural products in the development of antiviral agents against SARS-CoV-2: potential and prospects. Mar Life Sci Technol. 2024;6(2):280-297. doi:10.1007/s42995-023-00215-9

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Singh R, Chauhan N, Kuddus M. Exploring the therapeutic potential of marine-derived bioactive compounds against COVID-19. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021;28(38):52798-52809. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-16104-6

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Guarner J. Three Emerging Coronaviruses in Two Decades. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;153(4):420-421. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqaa029

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Parker EPK, Shrotri M, Kampmann B. Keeping track of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine pipeline. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(11):650. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-00455-1

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Plante JA, Liu Y, Liu J, et al. Spike mutation D614G alters SARS-CoV-2 fitness. Nature. 2021;592(7852):116-121. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2895-3

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Tegally H, Wilkinson E, Giovanetti M, et al. Detection of a SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern in South Africa. Nature. 2021;592(7854):438-443. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03402-9

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271-280.e8. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Pillaiyar T, Manickam M, Namasivayam V, Hayashi Y, Jung SH. An Overview of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) 3CL Protease Inhibitors: Peptidomimetics and Small Molecule Chemotherapy. J Med Chem. 2016;59(14):6595-6628. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01461

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Munster VJ, Koopmans M, van Doremalen N, van Riel D, de Wit E. A Novel Coronavirus Emerging in China – Key Questions for Impact Assessment. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):692-694. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2000929

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Mayer AM, Rodríguez AD, Berlinck RG, Fusetani N. Marine pharmacology in 2007-8: Marine compounds with antibacterial, anticoagulant, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antimalarial, antiprotozoal, antituberculosis, and antiviral activities; affecting the immune and nervous system, and other miscellaneous mechanisms of action. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2011;153(2):191-222. doi:10.1016/j.cbpc.2010.08.008

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Atanasov AG, Waltenberger B, Pferschy-Wenzig EM, et al. Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: A review. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33(8):1582-1614. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.08.001

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Harvey AL, Edrada-Ebel R, Quinn RJ. The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14(2):111-129. doi:10.1038/nrd4510

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Tintore M, Vidal-Jordana A, Sastre-Garriga J. Treatment of multiple sclerosis: success from bench to bedside. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(1):53-58. doi:10.1038/s41582-018-0082-z

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Waltenberger B, Mocan A, Šmejkal K, Heiss EH, Atanasov AG. Natural Products to Counteract the Epidemic of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disorders. Molecules. 2016;21(6):807. doi:10.3390/molecules21060807

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Dhand R, Li J. Coughs and Sneezes: Their Role in Transmission of Respiratory Viral Infections, Including SARS-CoV-2. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(5):651-659. doi:10.1164/rccm.202004-1263PP

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Geahchan S, Ehrlich H, Rahman MA. The Anti-Viral Applications of Marine Resources for COVID-19 Treatment: An Overview. Mar Drugs. 2021;19(8):409. doi:10.3390/md19080409

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Guo ZD, Wang ZY, Zhang SF, et al. Aerosol and Surface Distribution of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 in Hospital Wards, Wuhan, China, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7):1583-1591. doi:10.3201/eid2607.200885

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Tran K, Cimon K, Severn M, Pessoa-Silva CL, Conly J. Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35797. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035797

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Lai Y, Yan Y, Liao S, et al. 3D-quantitative structure-activity relationship and antiviral effects of curcumin derivatives as potent inhibitors of influenza H1N1 neuraminidase. Arch Pharm Res. 2020;43(5):489-502. doi:10.1007/s12272-020-01230-5

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Uzair B, Mahmood Z, Tabassum S. Antiviral activity of natural products extracted from marine organisms. Bioimpacts. 2011;1(4):203-211. doi:10.5681/bi.2011.029

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199-1207. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001316

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Devi VK, Jain N, Valli KS. Importance of novel drug delivery systems in herbal medicines. Pharmacogn Rev. 2010;4(7):27-31. doi:10.4103/0973-7847.65322

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Rampogu S, Gajula RG, Lee G, Kim MO, Lee KW. Unravelling the therapeutic potential of marine drugs as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors: An insight from essential dynamics and free energy landscape. Comput Biol Med. 2021;135:104525. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104525

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Rahman MM, Islam MR, Shohag S, et al. Multifaceted role of natural sources for COVID-19 pandemic as marine drugs. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022;29(31):46527-46550. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-20328-5

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Okechukwu QN, Adepoju FO, Kanwugu ON, et al. Marine-Derived Bioactive Metabolites as a Potential Therapeutic Intervention in Managing Viral Diseases: Insights from the SARS-CoV-2 In Silico and Pre-Clinical Studies. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;17(3):328. doi:10.3390/ph17030328

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Mishra P, Sohrab S, Mishra SK. A review on the phytochemical and pharmacological properties of Hyptis suaveolens (L.) Poit. Futur J Pharm Sci. 2021;7(1):65. doi:10.1186/s43094-021-00219-1

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Layqah LA, Eissa S. An electrochemical immunosensor for the coronavirus associated with the Middle East respiratory syndrome using an array of gold nanoparticle-modified carbon electrodes. Mikrochim Acta. 2019;186(4):224. doi:10.1007/s00604-019-3345-5

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Palmieri V, Papi M. Can graphene take part in the fight against COVID-19?. Nano Today. 2020;33:100883. doi:10.1016/j.nantod.2020.100883

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Dacrory S. Antimicrobial Activity, DFT Calculations, and Molecular Docking of Dialdehyde Cellulose/Graphene Oxide Film Against Covid-19. J Polym Environ. 2021;29(7):2248-2260. doi:10.1007/s10924-020-02039-5

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Lobo-Galo N, Gálvez-Ruíz JC, Balderrama-Carmona AP, Silva-Beltrán NP, Ruiz-Bustos E. Recent biotechnological advances as potential intervention strategies against COVID-19. 3 Biotech. 2021;11(2):41. doi:10.1007/s13205-020-02619-1

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Hashemi B, Akram FA, Amirazad H, et al. Emerging importance of nanotechnology-based approaches to control the COVID-19 pandemic; focus on nanomedicine iterance in diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 patients. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2022;67:102967. doi:10.1016/j.jddst.2021.102967

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Jia Q, Fu J, Liang P, et al. Investigating interactions between chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine and their single enantiomers and angiotensin-converting enzyme two by a cell membrane chromatography method. J Sep Sci. 2022;45(2):456-467. doi:10.1002/jssc.202100570

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Tang WF, Tsai HP, Chang YH, et al. Perilla (Perilla frutescens) leaf extract inhibits SARS-CoV-2 via direct virus inactivation. Biomed J. 2021;44(3):293-303. doi:10.1016/j.bj.2021.01.005

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Yi M, Lin S, Zhang B, Jin H, Ding L. Antiviral potential of natural products from marine microbes. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;207:112790. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112790

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Mossaad E, Furuyama W, Enomoto M, Kawai S, Mikoshiba K, Kawazu S. Simultaneous administration of 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate and chloroquine reverses chloroquine resistance in malaria parasites. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(5):2890-2892. doi:10.1128/AAC.04805-14

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Alobaida A, Abouzied AS, Younes KM, Alzhrani RM, Alsaab HO, Huwaimel B. Analyzing energetics and dynamics of hepatitis C virus polymerase interactions with marine bacterial compounds: a computational study. Mol Divers. 2025;29(2):1245-1260. doi:10.1007/s11030-024-10904-x

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Roy A, Das R, Roy D, et al. Encapsulated hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine into cyclic oligosaccharides are the potential therapeutics for COVID-19: insights from first-principles calculations. J Mol Struct. 2022;1247:131371. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131371

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Chen Z, Liu A, Cheng Y, et al. Hydroxychloroquine/chloroquine in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):805. doi:10.1186/s12879-021-06477-x

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Yao Q, Xing Y, Ma J, Wang C, Zang J, Zhao G. Binding of Chloroquine to Whey Protein Relieves Its Cytotoxicity while Enhancing Its Uptake by Cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69(36):10669-10677. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.1c04140

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Zazo H, Colino CI, Lanao JM. Current applications of nanoparticles in infectious diseases. J Control Release. 2016;224:86-102. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.01.008

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Gagliardi M. Biomimetic and bioinspired nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery. The Delivery. 2017;8(5):289-299. doi:10.4155/tde-2017-0013

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Chen L, Liang J. An overview of functional nanoparticles as novel emerging antiviral therapeutic agents. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2020;112:110924. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2020.110924

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Gurunathan S, Qasim M, Choi Y, et al. Antiviral Potential of Nanoparticles-Can Nanoparticles Fight Against Coronaviruses?. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2020;10(9):1645. doi:10.3390/nano10091645

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Sathasivam R, Radhakrishnan R, Hashem A, Abd Allah EF. Microalgae metabolites: A rich source for food and medicine. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2019;26(4):709-722. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2017.11.003

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Lee C. Griffithsin, a Highly Potent Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Lectin from Red Algae: From Discovery to Clinical Application. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(10):567. doi:10.3390/md17100567

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Levendosky K, Mizenina O, Martinelli E, et al. Griffithsin and Carrageenan Combination To Target Herpes Simplex Virus 2 and Human Papillomavirus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(12):7290-7298. doi:10.1128/AAC.01816-15

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - O’Keefe BR, Giomarelli B, Barnard DL, et al. Broad-spectrum in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy of the antiviral protein griffithsin against emerging viruses of the family Coronaviridae. J Virol. 2010;84(5):2511-2521. doi:10.1128/JVI.02322-09

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Morokutti-Kurz M, Fröba M, Graf P, et al. Iota-carrageenan neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 and inhibits viral replication in vitro. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0237480. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0237480

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Moulaei T, Alexandre KB, Shenoy SR, et al. Griffithsin tandemers: flexible and potent lectin inhibitors of the human immunodeficiency virus. Retrovirology. 2015;12:6. doi:10.1186/s12977-014-0127-3

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Lee C. Griffithsin, a Highly Potent Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Lectin from Red Algae: From Discovery to Clinical Application. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(10):567. doi:10.3390/md17100567

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - O’Keefe BR, Vojdani F, Buffa V, et al. Scaleable manufacture of HIV-1 entryinhibitor griffithsin and validation of its safety and efficacy as a topical microbicide component. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(15):6099-6104. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901506106

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Lusvarghi S, Bewley CA. Griffithsin: An Antiviral Lectin with Outstanding Therapeutic Potential. Viruses. 2016;8(10):296. doi:10.3390/v8100296

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Buck CB, Thompson CD, Roberts JN, Müller M, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Carrageenan is a potent inhibitor of papillomavirus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2(7):e69. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0020069

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Rodrigues Felix C, Gupta R, Geden S, et al. Selective Killing of Dormant Mycobacterium tuberculosis by Marine Natural Products. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(8):e00743-17. doi:10.1128/AAC.00743-17

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Friedland BA, Hoesley CJ, Plagianos M, et al. First-in-Human Trial of MIV-150 and Zinc Acetate Coformulated in a Carrageenan Gel: Safety, Pharmacokinetics, Acceptability, Adherence, and Pharmacodynamics. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):489-496. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000001136

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Hebar A, Koller C, Seifert JM, et al. Non-clinical safety evaluation of intranasal iota-carrageenan. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122911. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0122911

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). CFR – Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. 2024.

CFR – Code of Federal Regulations Title 21 - Yasuhara-Bell J, Lu Y. Marine compounds and their antiviral activities. Antiviral Res. 2010;86(3):231-240. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.03.009

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Li YX, Wijesekara I, Li Y, Kim SK. Phlorotannins as bioactive agents from brown algae. Process Biochem. 2011;46(12):2219–2224. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2011.09.015

Crossref | Google Scholar - Heo SJ, Ko SC, Cha SH, et al. Effect of phlorotannins isolated from Ecklonia cava on melanogenesis and their protective effect against photo-oxidative stress induced by UV-B radiation. Toxicol In Vitro. 2009;23(6):1123-1130. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2009.05.013

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Yoon NY, Eom TK, Kim MM, Kim SK. Inhibitory effect of phlorotannins isolated from Ecklonia cava on mushroom tyrosinase activity and melanin formation in mouse B16F10 melanoma cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57(10):4124-4129. doi:10.1021/jf900006f

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Kong CS, Kim JA, Yoon NY, Kim SK. Induction of apoptosis by phloroglucinol derivative from Ecklonia Cava in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47(7):1653-1658. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2009.04.013

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Artan M, Li Y, Karadeniz F, Lee SH, Kim MM, Kim SK. Anti-HIV-1 activity of phloroglucinol derivative, 6,6′-bieckol, from Ecklonia cava. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16(17):7921-7926. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2008.07.078

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Zhang R, Kang KA, Piao MJ, et al. Eckol protects V79-4 lung fibroblast cells against gamma-ray radiation-induced apoptosis via the scavenging of reactive oxygen species and inhibiting of the c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;591(1-3):114-123. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.086

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Myung CS, Shin HC, Bao HY, Yeo SJ, Lee BH, Kang JS. Improvement of memory by dieckol and phlorofucofuroeckol in ethanol-treated mice: possible involvement of the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase. Arch Pharm Res. 2005;28(6):691-698. doi:10.1007/BF02969360

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Khan MT, Ali A, Wang Q, et al. Marine natural compounds as potents inhibitors against the main protease of SARS-CoV-2-a molecular dynamic study. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;39(10):3627-3637. doi:10.1080/07391102.2020.1769733

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Park JY, Ko JA, Kim DW, et al. Chalcones isolated from Angelica keiskei inhibit cysteine proteases of SARS-CoV. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2016;31(1):23-30. doi:10.3109/14756366.2014.1003215

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Hirata T, Tanaka M, Ooike M, Tsunomura T, Sakaguchi M. Antioxidant activities of phycocyanobilin prepared from Spirulina platensis. J Appl Phycol. 2000;12(5):435-439. doi:10.1023/A:1008175217194

Crossref | Google Scholar - Pendyala B, Patras A. In silico Screening of Food Bioactive Compounds to Predict Potential Inhibitors of COVID-19 Main protease (Mpro) and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). ChemRxiv. 2020. doi:10.26434/chemrxiv.12051927.v2

Crossref | Google Scholar - Sun QL, Li Y, Ni LQ, et al. Structural characterization and antiviral activity of two fucoidans from the brown algae Sargassum henslowianum. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;229:115487. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115487

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Kwon PS, Oh H, Kwon SJ, et al. Sulfated polysaccharides effectively inhibit SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Cell Discov. 2020;6(1):50. doi:10.1038/s41421-020-00192-8

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Vijayaraj R, Altaff K, Rosita AS, Ramadevi S, Revathy J. Bioactive compounds from marine resources against novel corona virus (2019-nCoV): in silico study for corona viral drug. Nat Prod Res. 2021;35(23):5525-5529. doi:10.1080/14786419.2020.1791115

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Zakaryan H, Arabyan E, Oo A, Zandi K. Flavonoids: promising natural compounds against viral infections. Arch Virol. 2017;162(9):2539-2551. doi:10.1007/s00705-017-3417-y

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Khan MT, Ali A, Wang Q, et al. Marine natural compounds as potents inhibitors against the main protease of SARS-CoV-2-a molecular dynamic study. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;39(10):3627-3637. doi:10.1080/07391102.2020.1769733

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Letko M, Marzi A, Munster V. Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(4):562-569. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

Not reported

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Magaji Amayindi

Department of Pure and Industrial Chemistry

Bayero University Kano, Nigeria

Email: magajiamayindi@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Jimoh Yakubu Onimisi

Department of Biochemistry

Federal University Wukari, Nigeria

Joel Yakubu

Department of Community Health

Taraba State College of Health Technology, Nigeria

Rubiyamisumma Dorcas Kaduna

Department of Science Education

Adamawa State University, Nigeria

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest Statement

Not reported

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Magaji A, Jimoh OY, Joel Y, Rubiyamisumma DK. Role of Marine Natural Products in Combating SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. medtigo J Pharmacol. 2025;2(2):e3061222. doi:10.63096/medtigo3061222 Crossref