Author Affiliations

Abstract

Objective: This study was carried out to determine the risk factors associated with hearing impairment among primary school deaf children in the Gaza Strip.

Methodology: This was a retrospective study of preschool deaf children. It was conducted over a period of 4 months (February to June 2021). Data was collected from consenting parents by using a pretested structured interview questionnaire. Data was entered, managed, and analyzed by using statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) software version 19. Descriptive statistics were used to present and express the data as simple tables and charts.

Results: the participants’ response rate was 74% response rate. The mean age of the participants was 11.5 years ± 3.8. 71.6% of parents were close relatives, 82.4% of the children were discovered as deaf before the age of 3 years, and 63.5% have another deaf child or more in the family. The common type of hearing impairment was sensorineural hearing loss, 64.9%, 18.9% had profound hearing impairment, and 78.4% were using hearing aids, which reflects the highest percentage of severe to profound hearing loss. The most common identified risk factors associated with hearing impairment rather than consanguinity marriage include recurrent otitis media and exposure to high noise/explosions 39.1% for each, earwax impaction 29.7%, neonatal jaundice and mother took medicine during pregnancy 24.3% for each, child infected with chickenpox 23%, recurrent tonsillitis 21.6%, ear surgery 17.6%, febrile illnesses 14.9%, and birth asphyxia.

Conclusion: This study shows that consanguinity marriage, recurrent otitis media, exposure to noise, earwax impaction, neonatal jaundice, and mothers having medical conditions during pregnancy are risk factors for hearing impairment among school deaf children in the Gaza Strip.

Keywords

Hearing impairment, Deaf child, Risk factors, Gaza strip, Hearing loss.

Introduction

Hearing is one of our five senses; it gives us access to sounds in the world around us. Hearing loss or impairment is defined as a partial or full decrease in the ability to detect and hear sounds.[1] Recognizing the importance of early detection, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that every newborn be screened for hearing loss as early as possible, usually before they leave the hospital.[2] Around 466 million people worldwide have a hearing disability, 34 million of these are children, and it is estimated that by 2050, over 900 million people will have disabling hearing loss.[3] Common causes of hearing loss and deafness can be either acquired; meaning that the loss occurred after birth, due to injury or illness like ear infections- mumps, measles, ototoxic drugs e.g. aminoglycosides and loop diuretics, foreign body, wax, childhood diseases such as mumps, measles, and trauma- both direct (fracture of petrous temporal bone, tympanic membrane perforation) and indirect (following a slap to the face, an explosion or barotrauma), or congenital meaning that the hearing loss or deafness was present at birth and could be due to osteogenesis imperfect, otosclerosis cystic fibrosis, cleft palate, family history of hearing loss or deafness, infections during pregnancy like rubella, and complications during pregnancy such as the Rh factor, maternal diabetes, or toxicity.[4,5,6,7]

Hearing loss is generally described as slight/mild- the person has trouble hearing and understanding soft speech, speech from a distance or speech in background of noise, moderate- the person has difficulty hearing regular speech, even at close distances this may affect language development, interaction with peers and self-esteem), severe- the person may hear very loud speech or loud environmental sound such as a siren or a door slamming, or profound- the person may perceive loud sounds as vibrations (speech and language may deteriorate).[8] Impairment of hearing can occur in either or both ears, and may exist in only one ear or in both ears. Generally, only children whose hearing loss is greater than 90 decibels are considered deaf.[1] Hearing loss or deafness can be classified based on the site of the lesion- peripheral or central. Peripheral hearing loss results from dysfunction in the transmission of sound through the external or middle ear or by abnormal transduction of sound energy into neural activity in the inner ear and the 8th nerve.[6] Deaf children are those with severe to profound hearing loss, which implies very little or no hearing. Hearing devices, such as cochlear implants, may help them to hear and learn speech. In learning to communicate, such children may benefit from visual reinforcement, such as signs, cued speech, and lip reading.[9]

Hearing impairment or loss is a silent or invisible disability; it may therefore not be apparent to advocates and health professionals. The negative impact of hearing impairment or loss has been well documented. In children, hearing disability impedes speech and language development and sets the affected children on a trajectory of limited educational and vocational attainment. Children with hearing impairment may also be at risk of violence.[10,11] The impact on the family is equally profound. Parents of children who are deaf or hard of hearing must deal with specific challenges, are often at greater risk of stress, have higher out-of-pocket expenses, and lose more workdays than other parents.[12] Untreated hearing loss also affects social and economic development in communities and countries.[13] The prevalence of people with disability is 5.8%, out of this 1.5% had hearing disability; 37.6% are children below 17 years, and 53% were not involved in school teaching at all, 46.5% need hearing aids, and 14.3% need cochlear implants. Among the causes of hearing disability, 24.6% are congenital, and 72.2% are acquired causes. Also, 24.2% need modified features to continue their education.[14] The prevalence of hearing loss vary from one area to another worldwide; 0.5% in high-income countries, 1.6% in Central/Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Sub-Sahara Africa 1.9%, Middle East and North Africa 0.9%, South Asia 2.4%, Latin America And Caribbean 1.6, and worldwide 1.7%. With the aging of the world population, the percentage among those aged 15 years and over is expected to double by 2030-2050, and hearing impairment is considered the most prevalent impairment worldwide.[3] The aim of this study was to determine the risk factors associated with hearing impairment among primary school deaf children in the Gaza Strip. No recent studies targeting risk factors or causes of hearing impairment or hearing loss in the Gaza Strip have been done.

Methodology

Design: A retrospective, descriptive cross-sectional design was used.

Settings: The primary schools for deaf children in the Gaza Strip, Palestine.

Study Population: The total pupil population was 285, males were more prevalent than females, with 54% and 46% respectively.

Sample size and sampling: 100 children were chosen randomly and proportionally according to the school size.

Instrument: A pretested structured interview questionnaire with the child’s mother, including demographic data, mother’s health during pregnancy, child’s growth and development, problems encountered during and after delivery, diseases and injuries occurred during infancy and early childhood, and other associated medical problems.

Data collection: After obtaining the ethical approval, the researcher’s assistants met the selected children’s mothers who met the selection criteria (age from 6-15 years and whose parents gave consent during the period from February to June 2021. Children whose parents refused to participate in the study were excluded.

Statistical analysis: SPSS, Version 19, was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to describe demographic and main variables (frequencies and percentages for categorical data and mean and standard deviation for continuous variables).

Results

Of the 100 consent forms given to the children’s parents, only 74 were returned signed, consenting to participate in the study, with a 74% response rate. There was an equal percentage (50%) for male and female children. The mean age of the participants was 11.5 years ± 3.8. The majority of parents were educated low (secondary school and less); 63.5% and 82.4% for fathers and mothers, respectively. The prevalence of consanguinity marriage was 71.6%, which is a high prevalence expected to have hereditary hearing loss. Only 10.8% of children were low birth weight, and 82.4% of the children were discovered as deaf before the age 3 years. Also, 63.5% have another deaf child or more in the family. The sociodemographic characteristics are illustrated in Table 1.

| Character | Frequency (%) | Percentage (%) |

| Sex

Male Female School Atfaluna for Deaf Al-Hanan for Rehabilitation Al-Amal for Deaf Rehabilitation Father’s Education Illiterate Secondary and less University Mother’s Education Illiterate Secondary and less University Parents relationship 1st degree relatives Not relatives Presence of other deaf kids in the family Yes No Weight at birth Low birth weight(<2500gm) Normal Age of discovery Before 3 years After 3 years |

37 37 32 25 17 10 47 17 4 61 9 53 21 47 27 8 66 61 13 |

50 50 43.2 33.8 23.0 13.5 63.5 23.0 5.4 82.4 12.2 71.6 23.4 63.5 36.5 10.8 89.2 82.4 17.6 |

| Mean age 11.5 ± 3.8 | ||

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants (n=74)

The risk factors associated with hearing impairment as stated by mothers when first diagnosed rather than consanguinity marriage include: recurrent otitis media and exposure to high noise/explosions 39.1% for each, earwax impaction 29.7%, neonatal jaundice and mother took medicine during pregnancy 24.3% for each, child infected with chickenpox 23%, recurrent tonsillitis 21.6%, ear surgery 17.6%, febrile illnesses 14.9%, birth asphyxia 13.5%, head trauma 12.2%, and meningitis and direct trauma to the ear 9.5% for each. Table 2 shows the risk factors of hearing impairment among children.

| Risk factors | Frequency(n) | Percentage(%) |

| Mother took medicine

Birth asphyxia Neonatal jaundice Chickenpox Earwax impaction Febrile illness Recurrent tonsillitis Head trauma Recurrent otitis media Direct trauma to the ear Ear surgery Meningitis Exposure to high noise/explosion |

18

10 18 17 22 11 16 9 29 7 13 7 29

|

24.3

13.5 24.3 23.0 29.7 14.9 21.6 12.2 39.1 9.5 17.6 9.5 39.1 |

Table 2: Risk factors associated with hearing impairment among the study participants

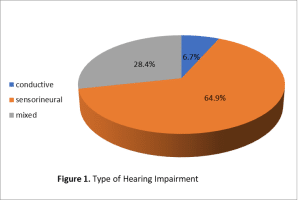

The common type of hearing impairment was sensorineural hearing loss, 64.9%, followed by mixed hearing loss and conductive hearing loss, 28.4% and 6.7%, respectively, as demonstrated in Figure 1. The severity of hearing impairment, as shown in Table 3, 18.9% had profound hearing impairment, the majority, 48.6 %, had severe hearing impairment, 27% had moderate hearing impairment, and only 5.4% had mild hearing impairment. On the other hand, 78.4% were using hearing aids, and this reflects the highest percentage of severe to profound hearing loss.

| Degree of hearing impairment | Frequency(n) | Percentage (%) |

| Profound | 14 | 19.0 |

| Sever | 36 | 48.6 |

| Moderate | 20 | 27.0 |

| Mild | 4 | 5.4 |

| Use of a hearing aid | ||

| Yes | 58 | 78.4 |

| No | 16 | 21.6 |

Table 3: Degree of hearing impairment and the use of hearing aid

Discussion

The factors that contribute to hearing impairment among children worldwide are multifactorial; they vary depending on the environment of the child and the circumstances that surround the child’s birth and pregnancy history. In this study the majority of children were detected before the age 3 years, this finding is different from findings by other researchers [15,16,17] and in their studies this indicates that the surveillance system regarding hearing impairment is well functioning, and families are highly oriented to discovering their kids earlier. Most of the parents are 1st degree relatives and most of the families have more than one kid with hearing impairment, this means hereditary factor may represent the main cause of hearing impairment among Palestinian children, so awareness raising regarding consanguinity marriage among these families and the risk of getting deaf child is very essential. The parental education does not affect the pattern of hearing impairment, in contrast to another report that hearing impairment is more common in children whose mothers are less educated.[18] The commonly noticed risk factors associated with hearing impairment in this study were exposure to high noise, recurrent ear infection (otitis media), earwax impaction, neonatal jaundice, chickenpox, recurrent tonsillitis, and febrile convulsions. These findings were similar to those identified by other research results and reports.[4,9,15,17,19] With the exception of consanguinity marriage, the identified risk factors are preventable and can be easily managed in primary health care centers by trained primary health care workers. Sensorineural hearing loss was the most prevalent type of hearing impairment seen among the children; this is similar to the results of Colombian and Sudanese research [20,21] but differs from other studies in which conductive deafness was more common.[22,23,24] This study determined the risk factors associated with hearing impairment among primary school deaf children in the Gaza Strip. These findings, therefore, encourage screening at birth to enhance early detection and prevention of hearing impairment. More and better, wider studies are needed to identify the real and exact causes of hearing impairment with adequate funding and a skillful research team.

Conclusion

The study found that consanguinity marriage is highly prevalent among parents of the deaf children involved. Most of the risk factors identified are preventable risk factors and could be managed earlier, reducing the rate of hearing impairment among children.

References

- National Centre for Education Statistics. Deafness and Hearing Loss. NICHCY Disability Fact Sheet 2016. Deafness and Hearing Loss

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI). Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI)

- World Health Organization. Deafness and Hearing Loss. Deafness and Hearing Loss.

- The Merck Manual’s Online Medical Library. Hearing Loss and Deafness. Hearing Loss and Deafness

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Causes of Hearing Loss in Children. Causes of Hearing Loss in Children

- Billings KR, Kenna MA. Causes of pediatric sensorineural hearing loss: yesterday and today. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125(5):517–521. doi.10.1001/archotol.125.5.517 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Haddad J. Hearing loss. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson BH, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 17th ed. W.B. Saunders Company; 2004:2129-2135. Hearing loss

- World Health Organization. Childhood Hearing Loss: Strategies for Prevention and Care. 2016. Childhood Hearing Loss: Strategies for Prevention and Care

- World Health Organization. Hearing loss. Deafness and hearing loss

- Olusanya BO, Neumann KJ, Saunders JE. The global burden of disabling hearing impairment: a call to action. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(5):367-373. doi.10.2471/BLT.13.128728 PubMed| Crossref | Google Scholar

- Md Daud MK, Mohd Noor R, Abd Rahman N, Sidek DS, Mohamad A. The effect of mild hearing loss on academic performance in primary school children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(1):67-70. doi.10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.10.013 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Barton GR, Stacey PC, Fortnum HM, Summerfield AQ. Hearing-impaired children in the United Kingdom, IV: cost-effectiveness of pediatric cochlear implantation. Ear Hear. 2006;27(5):575-588. doi.10.1097/01.aud.0000233967.11072.24 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mohr PE, Feldman JJ, Dunbar JL, et al. The societal costs of severe to profound hearing loss in the United States. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2000;16(4):1120-1135. doi.10.1017/s0266462300103162 Pubmed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Population, Housing and Establishment Census 2017. 2018. Population, Housing and Establishment Census 2017

- Dunmade AD, Segun-Busari S, Olajide TG, Ologe FE. Profound bilateral sensorineural hearing loss in Nigerian children: any shift in etiology? J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2007;12(1):112-118. doi.10.1093/deafed/enl019 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kumar S, Aramani A, Mathew M, Bhat M, Rao VV. Prevalence of hearing impairment amongst school-going children in the rural field practice area of the institution. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;71(Suppl 2):1567-1571. doi.10.1007/s12070-019-01651-9 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Adegbiji WA, Olajide GT, Olatoke F, et al. Preschool children hearing impairment: prevalence, diagnosis, and management in a developing country. Int Tinnitus J. 2018;22(1):60-65. doi.10.5935/0946-5448.20180010 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hearing Impairment. 2017. Hearing loss

- Lin Lin CY, Tseng YC, Guo HR, Lai DC. Prevalence of childhood hearing impairment of different severities in urban and rural areas: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3): e020955 doi.10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020955 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Díaz E, Neira-Torres L. The prevalence of hearing loss in children in Colombia. Rev Fac Med. 2015;62(4):529-538. The prevalence of hearing loss in children in Colombia.

- Ahmed S, Hajabubher MA, Satti AA. Risk factors and management modalities for Sudanese children with hearing loss or hearing impairment done in Aldwha and Khartoum ENT hospitals, Sudan. Ann Trop Med Public Health. 2017;10(2):357-361. Risk factors and management modalities for Sudanese children with hearing loss or hearing impairment done in Aldwha and Khartoum ENT hospitals

- Obukowho OL, Enekole OJ, Ifeoma A. Risk factors of hearing impairment among lower primary school children in Port Harcourt. Glob J Otolaryngol. 2017;5:555675 Risk factors of hearing impairment among lower primary school children in Port Harcourt

- Taha AA, Pratt SR, Farahat TM, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of hearing impairment among primary-school children in Shebin El-Kom District, Egypt. Am J Audiol. 2010;19(1):46-60. doi.10.1044/1059-0889(2010/09-0030) PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Md Daud MK, Mohd Noor R, Abd Rahman N, Sidek DS, Mohamad A. The effect of mild hearing loss on academic performance in primary school children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(1):67-70. doi.10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.10.013 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not applicable

Funding

Not applicable

Author Information

Hatem S El-Dabbakeh

Department of Public Health

University College of Ability Development, Gaza Strip, Palestine

Email: hdabbakeh@palestinercs.org

Author Contribution

The author contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles and was involved in the writing – original draft preparation and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the research ethical committee of university college of Ability and Development with reference no. 02/Jan/2021.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Not reported

Guarantor

Not reported

DOI

Cite this Article

Hatem SE. Risk Factors for Hearing Impairment Among Primary School Deaf Children in Gaza Strip, Palestine. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622423. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622423 Crossref