Author Affiliations

Abstract

Background: Graduate medical education (GME) is immensely important in preparing residents to become independent practitioners, especially in non-metropolitan areas. Research is necessary to understand the effects of the introduction of a new residency program on patient experience of care measures. Aim: This study investigated the impact of a new residency program on emergency department (ED) patient satisfaction in a rural setting.

Methodology: This retrospective quasi-experimental study of satisfaction surveys returned to a single community hospital, which occurred between July 2019 and November 2023. The comparison groups were resident-shared versus attending solo visits. Outcomes were percentages of top box score for the “Overall rating of care” and “Doctors” questions. Chi-square and odds ratios statistics were used.

Results: Of the 1,696 of 1,851 (91.6 %) surveys returned, 155 of them were excluded. The pre- and post-startup periods demonstrated statistically comparable patient experience performance across all physician metrics. Importantly, resident physicians-led visits were equivalent to solo attending visits for all patients’ experience measures of care. Multivariate analyses found that an elderly male patient yielded the best odds of a top box rating, while same-day transfer from an urgent care to the ED gave higher odds of a dissatisfied patient.

Conclusion: Results from this single rural site study offer reassurance to GME and hospital stakeholders that resident physicians exert a neutral to net positive influence on patients’ perception of care. In the current landscape of physician workforce shortage, health systems should feel confident with the potential benefit of introducing resident physicians to the care team.

Keywords

Patient experience, Patient satisfaction, Emergency department, Resident physicians, Attending physicians, Emergency medicine residency, Concern for comfort, courtesy, Took time to listen, Informative of treatment.

Introduction

The Emergency Department (ED) is a unique environment within the United States healthcare system, comprising 28 % of all acute care visits, while bridging the worlds of outpatient and inpatient care. The Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) viewed patient satisfaction as an important proxy for health care value, with third-party vendors assuming the responsibility of administering the Emergency Department Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (ED CAHPS) survey.[1] Numerous published studies have linked patient satisfaction to both non-modifiable (e.g., overcrowding and boarding) and modifiable factors (e.g., desired interpersonal behaviors and communication tactics).[2-6] Most hospital leaders consider the “overall rating of care” question to be the true key performance indicator. Despite ongoing debate as to whether the various touch points of an emergency visit can be measured objectively, hospital reimbursement and clinician compensation are increasingly tied to patient satisfaction performance.[7,8]

In the academic hospital setting, resident physicians participate in significant clinician–patient interactions. Prior studies have shown that resident physicians influence satisfaction scores measurably.[9,10] Survey vendors report patient experience data by site and attending provider. However, they are mostly unable to directly report individualized data by resident, challenging a program’s ability to evaluate a resident trainee’s contribution to overall performance.[11] Moreover, attending physicians typically see very few patients on their own, which further confounds data interpretation.[10]

Building on these prior findings, the present study explored this topic in the context of a brand-new emergency medicine (EM) residency program. We aimed to investigate whether the incorporation of resident physicians improved overall patient satisfaction performance compared to solo attending physicians during the same period. The hypothesis was that resident physicians improved patients’ perception of medical care over attending physicians working without residents.

Methodology

Methodology and data sources: This is an observational retrospective quasi-experiment study, which adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.[12] The setting consisted of a single rural community ED with a Level 2 trauma center designation. The annual census is approximately 57,000, with 15 % pediatric visits and an admission rate of 25 %. In July 2020, the inaugural class matriculated in our EM residency, which is a three-year, Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)-accredited program with six resident physicians per year. All patients, regardless of age, who were discharged directly from the ED formed the study population. Exclusion criteria included patients who were prisoners, patients who presented with a psychiatric complaint, or cases managed by a non-physician (nurse practitioner or physician assistant). The eventual retrospective cohort consisted of a randomized sample of “treat-and-street” patients who responded to the ED CAHPS survey administered by Press Ganey, a third-party vendor, between July 2019 and November 2023. Survey modalities consisted of electronic or U.S. mail. Patients or patient proxies were asked to respond to each question using a five-point Likert scale (1 = very poor, 2 = poor, 3 = fair, 4 = good, 5 = very good). The pertinent questions from the ED survey are included in the supplemental material (see Supplemental Digital Content 1).

Supplemental digital content 1:

- Overall assessment

Overall rating of care received during your visit?

- Care providers’ assessment

During your visit, your care was provided primarily by a doctor, physician assistant (PA), nurse practitioner (NP), or midwife. Please answer the following questions with that healthcare provider in mind.

- Doctor’s question 1: Courtesy of the doctors.

- Doctor’s question 2: How well did the doctors take the time to listen to you?

- Doctor’s question 3: Doctors’ concern to keep you informed about your treatment.

- Doctor’s question 4: Doctors’ concern for your comfort while treating you.

The data set from our quasi-experimental retrospective study was sampled from three distinct time periods. The first was the pre-residency 8-month period from July 1, 2019, to February 29, 2020. The second was the post-residency startup 8-month period from July 1, 2020, to February 28, 2021. The third and final period was a 22-month stint between February 1, 2022, and November 30, 2023. The focus of the overall study was to compare patient satisfaction performance between resident-shared and attending-solo visits during the combined 38-month period.

Variables: Physician type (attending versus resident), patient age, gender, time of ED visit, acuity of visit, Charlson co-morbidity index, and transfer status from urgent care to ED were the key independent variables investigated. Dependent variables consisted of one primary outcome and four secondary outcomes. The primary outcome was the percentage of a score of 5 (top box) for the overall rating of care question. Secondary outcomes included the percentages of a score of 5 for the four individual physician-specific questions.

Statistical analysis: We explored key demographic and clinical variables in the dataset using either proportions, medians, or interquartile range, as appropriate. Categorical data were presented as frequency count (percentage) and compared between groups (attending-solo versus resident-shared visits) using Chi-square tests. Age was presented with the median (interquartile range) and compared between groups with the Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon test. The number and percentage of respondents who gave a score of 5 were reported and compared between groups with chi-squared statistics. The four doctors ’ questions were: courtesy, took time to listen, informative of treatment, and concern for comfort. Logistic regression was used to model the odds of a score of 5 on the overall rating of care question univariately with demographic and visit characteristics. The odds of a doctor’s score of all 5’s were also modeled. Results were presented with maximum likelihood odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals, and Wald Chi-square p-values. Multivariate logistic regression models were also used, starting with factors that were univariately significant with p < 0.10 and then eliminating factors one-at-a-time (backward elimination) until all remaining factors were significant with p < 0.05. The final participant sample size was adequately powered to observe a difference of less than 9 % between groups. Data were analyzed with SAS v9.4. This research required two separate Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviews covering the 2019-2021 and 2022-2023 periods, respectively. Mercy Health IRB deemed both applications to be exempt.

Results

The sample included 1,696 of 1,851 (91.6 %) surveys, 155 of which were excluded per IRB protocol. Table 1 presents the descriptive demographic statistics for both attending solo versus resident-shared visits. Out of a total of 1,696 visits, 1,044 (61.6%) attended solo, and 652 (38.4%) were resident-shared cases. Both groups had comparable female, Emergency Severity Index (ESI), Charlson comorbidity index, and same-day urgent care to ED transfer distributions. Attending-solo and resident-shared visits were different (p < 0.05) with respect to time of day – there were more shared visits in the morning than afternoon and night compared to the distribution of visits for attending only.

| 2019 – 2023 (n=1696) | |||

| Attending Solo | Resident-Shared | p-value | |

| No. Subjects | 1044 | 652 | |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 395 (37.8%) | 259 (39.7%) | 0.44 |

| Female | 649 (62.2%) | 393 (60.3%) | |

| Age, median years (IQR)1 | 60.2 (42,72) | 61.5 (46, 72) | 0.18 |

| 10, 90 Age | 22, 81 | 26, 80 | |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 957 (91.7%) | 590 (90.5%) | Overall p=0.43 |

| Black | 52 (5.0%) | 42 (6.4%) | |

| Other | 35 (3.4%) | 20 (3.1%) | |

| Time Day, n (%) | |||

| Morning | 426 (40.8%) | 343 (52.7%) | Overall p<0.001 |

| Afternoon | 469 (44.9%) | 248 (38.1%) | |

| Night | 149 (14.3%) | 60 (9.2%) | |

| ESI, n (%) | |||

| 1 or 2 | 100 (9.6%) | 77 (11.8%) | Overall p=0.34 |

| 3 | 828 (79.5%) | 506 (77.7%) | |

| 4 or 5 | 114 (10.9%) | 68 (10.5%) | |

| 2 missing | 1 missing | ||

| Charlson index | |||

| No co-morbidities | 309 (29.6%) | 172 (26.4%) | Overall p=0.28 |

| Mild (1,2) | 270 (25.9%) | 165 (25.3%) | |

| Moderate (3,4) | 250 (24.0%) | 181 (27.8%) | |

| Severe (5 or more) | 215 (20.6%) | 134 (20.6%) | |

| Transferred from urgent care to ED | |||

| Yes | 62 (5.9%) | 39 (6.0%) | 0.97 |

| No | 982 (94.1%) | 613 (94.0%) | |

Table 1: Patient demographics and visit characteristics

1IQR is interquartile range (25th percentile, 75th percentile).

2P-values are from Chi-square tests except for age, which uses a two-sided Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon test.

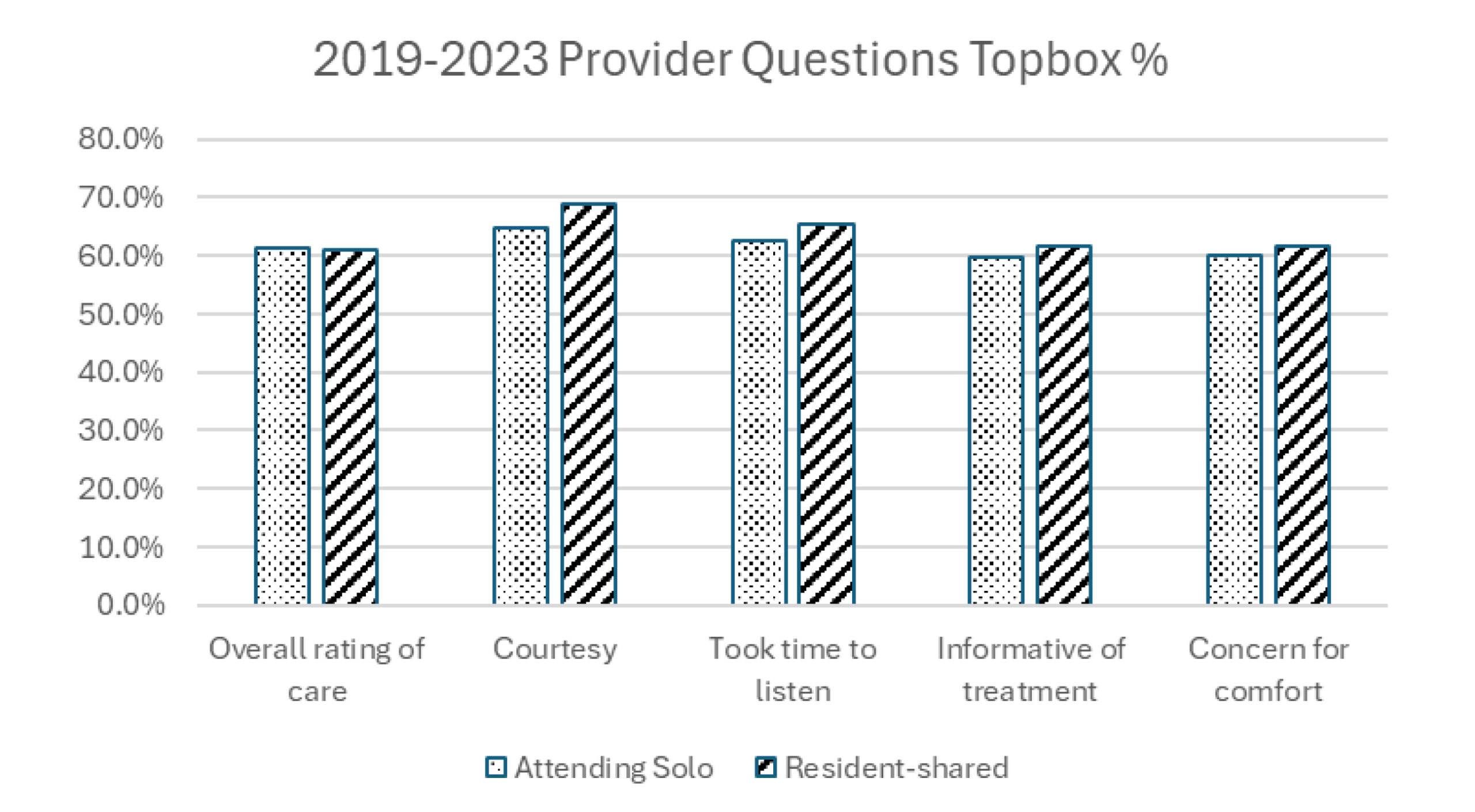

Figure 1 displays the primary and secondary outcome differences between the two groups. There were no statistically significant differences in the top box satisfaction scores between attending solo and resident-shared visits in terms of overall rating of care, or any of the individual doctors ’ questions.

Figure 1: Patient satisfaction for overall rating and doctor’s topbox

Table 2 summarizes the results of logistic regression analyses performed on the previously defined independent variables, which showed that, univariately, male gender, older age, higher Charlson index, and no same-day urgent care transfer yielded significantly increased odds of scoring top-box overall rating of care (with p < 0.05).

| 2019 – 2023 (n=1696) | ||

| Visit characteristic | Odds ratio2

(95% confidence interval (CI)) |

p-value |

| Resident Visit | ||

| Attending Only | 1.02 (0.83, 1.24) | 0.87 |

| Shared With Resident | Ref1 | |

| Patient’s gender | ||

| Male | 1.45 (1.18, 1.78) | <0.001 |

| Female | Ref1 | |

| Patient’s age (years) | 1.02 (1.02, 1.02)3 | <0.001 |

| Patient’s race | Overall p=0.09 | |

| White | Ref1 | |

| Black | 0.86 (0.56, 1.32) | 0.49 |

| Other | 0.55 (0.32, 0.95) | 0.04 |

| Time of visit | Overall p=0.72 | |

| Morning | 0.95 (0.69, 1.31) | 0.77 |

| Afternoon | 0.89 (0.65, 1.23) | 0.48 |

| Night | Ref1 | |

| Acuity | Overall p=0.56 | |

| ESI 1 or 2 | 1.11 (0.80, 1.54) | 0.54 |

| ESI 3 | Ref1 | |

| ESI 4 or 5 | 0.88 (0.64, 1.21) | 0.42 |

| Charlson index | Overall p<0.001 | |

| No co-morbidities | Ref1 | |

| Mild (1,2) | 1.65 (1.27, 2.15) | <0.001 |

| Moderate (3,4) | 2.44 (1.85, 3.21) | <0.001 |

| Severe (5 or more) | 2.47 (1.84, 3.31) | <0.001 |

| Transfer from urgent care to ED | ||

| Yes | Ref1 | |

| No | 2.06 (1.37, 3.10) | <0.001 |

Table 2: Univariate analysis of characteristics associated with odds of a score of 5 for the overall rating of care question

1Ref is the reference group.

2The Odds ratio is the odds of a score of 5 for each category compared to the reference category (e.g., the odds of giving a score of 5 were 1.45 times greater for males than females in the entire sample). 3The odds ratio for age is the increase in odds of a score of 5 for every 1-year increase in age.

Moreover, Table 3 shows that in a multivariate model, all but the Charlson index were associated with increased odds of a top-box overall rating as well.

| 2019 – 2023 (n=1696) | ||

| Visit characteristic | Odds ratio

(95% CI) |

p-value |

| Patient’s gender | ||

| Male | 1.43 (1.16, 1.76) | <0.001 |

| Female | ref | |

| Patient’s age (years) | 1.019 (1.014, 1.024) | <0.001 |

| Transfer from urgent care to ED | ||

| Yes | ref | |

| No | 2.08 (1.37, 3.17) | <0.001 |

Table 3: Multivariate analysis of characteristics associated with odds of a score of 5 for the overall rating of care question

For the secondary analysis, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups for all four doctors ’ questions. Of note, subgroup analyses performed on the most recent post-residency period (2022-2023, 980 data points) showed that while the overall rating of care was similar between attending-only and resident-shared visits, resident physicians demonstrated statistically significant improvement in top box performance for the individual doctor’s questions on courtesy (attending-solo 242/404 or 59.9% vs. resident-shared 390/570 or 68.4 %, p < 0.01) and took time to listen (attending-solo 231/401 or 57.6 % vs. resident-shared 371/572 or 64.9 %, p < 0.02).

Discussion

Research on the patient experience performance of resident physicians in ACGME-accredited programs is important because of the potential benefits and challenges of trainees. This study extends existing literature by examining the longitudinal performance differences between attending and resident physicians within the context of a new emergency medicine residency program. The most notable result of this research was that the incorporation of resident physicians into the care of ED patients yielded comparable overall rating of care scores compared to attending solo visits. Other interesting findings included: (1) An elderly male patient yielded the best odds of returning an overall top box rating. Age has previously been linked to improved patient satisfaction.[2] (2) Based on multivariate analysis, the odds of a patient transferred from an urgent care facility to the ED were 2.06 times more likely to be dissatisfied with the emergency care. (3) In the 22-month post-residency period from 2022-2023, which represented a more mature state of the residency program, resident-shared visits yielded higher proportions of a score of 5 compared to attending solo visits for the courtesy and took time to listen to questions. This latter finding seemed logical because patients in shared visits received face time from multiple physicians during the same ED visit.

Implications for policy and practices: ACGME milestones for Emergency Medicine stipulate the achievement of high standards in patient-provider communication, encompassing several core competencies of residency training, such as patient care, interpersonal and communication skills, and practice-based learning and improvement.[13] It has been reported in a prior study that without targeted training in patient experience, residents’ patient satisfaction performance tended to plateau during residency.[10] To fulfill the education mission and to improve the overall patient experience, many academic programs have implemented curricula to fill the resident training gap to learn best-practice behaviors and techniques, such as bedside presentation and practicing empathy and self-reflection.[9,14,15] Furthermore, resident-led visits were non-inferior to solo attending visits for all patient experience measures of care. Therefore, health systems should feel confident in the potential benefit of introducing resident physicians to the care team.

Limitations: There were some notable limitations in this study. Patient satisfaction scores collected by Press Ganey were attributed to the initial attending and resident physicians who composed the provider’s note. In a typical shift, a resident physician would sign out to the next shift’s resident. Therefore, some feedback intended for the correct team could have been misattributed. However, it was unlikely that this would have affected our primary outcome as we compared cumulative resident and attending data.

In addition, the initial study period between July 2019 and February 2021 (residency startup) coincided with the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. This could have affected the data comparison between the pre-residency and post-residency startup periods, as well as the validity of the combined dataset.[4] Also, the ED satisfaction surveys were only administered to discharged patients, who required less care time overall than admitted patients. This could potentially impact the applicability of our results to other three-year residency programs with significantly higher or lower admission rates.

Finally, there was a possibility that while residents were ramping up their workload as they progressed in their training within a new residency program, the attending physicians’ supervisory workload increased proportionately, which could have adversely impacted the attendings’ own patient satisfaction performance.[11]

For future work, there are opportunities to fine-tune the performance of resident physicians’ approach to improve overall patient satisfaction, such as the introduction of a standardized discharge tool as a best practice to enhance overall patient experience.[16]

Conclusion

Prior patient satisfaction studies in academic training programs underscored the challenges of isolating resident physicians’ effect on overall performance. The primary conclusion of our research was that resident-shared visits were comparable to attending solo visits for both the overall ED rating of care and all four individual doctors ’ questions. The increased touch time offered by resident physicians in shared visits demonstrated improved performance for the doctor’s specific questions regarding courtesy and taking time to listen. Consequently, in the context of a community-based academic EM residency program, the results from this research should reassure hospital leadership teams and graduate medical education stakeholders that resident physicians exert a neutral to net positive influence on patients’ perception of care in the Emergency Department.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Emergency Department CAHPS (ED CAHPS). 2024.

Emergency Department CAHPS (ED CAHPS) - Ferreira DC, Vieira I, Pedro MI, Caldas P, Varela M. Patient Satisfaction with Healthcare Services and the Techniques Used for its Assessment: A Systematic Literature Review and a Bibliometric Analysis. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(5):639. doi:10.3390/healthcare11050639

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Aaronson EL, Mort E, Sonis JD, Chang Y, White BA. Overall Emergency Department Rating: Identifying the Factors That Matter Most to Patient Experience. J Healthc Qual. 2018;40(6):367-376. doi:10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000129

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Jehle D, Leggett J, Short R, Pangia J, Wilson C, Gutovitz S. Influence of COVID-19 outbreak on emergency department Press Ganey scores of emergency physicians. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1(6):1413-1417. doi:10.1002/emp2.12287

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Pink E, Ding M, Murdoch I, Tan VIC. A Survey of Emergency Department Quality Improvement Activities: Effective Fast Track Waiting Area Management. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2019;41(2):145-149. doi:10.1097/TME.0000000000000223

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Wang W, Liu X, Shen X, et al. Emergency patients’ satisfaction with humanistic caring and its associated factors in Chinese hospitals: a multi-center cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1414032. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1414032

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Hoonakker PLT, Carayon P, Brown RL, et al. Satisfaction of Older Patients With Emergency Department Care: Psychometric Properties and Construct Validity of the Consumer Emergency Care Satisfaction Scale. J Nurs Care Qual. 2023;38(3):256-263. doi:10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000694

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Reznek MA, Larkin CM, Scheulen JJ, Harbertson CA, Michael SS. Operational factors associated with emergency department patient satisfaction: Analysis of the Academy of Administrators of Emergency Medicine/Association of Academic Chairs of Emergency Medicine national survey. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(7):753-760. doi:10.1111/acem.14278

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Holmes CT, Huggins C, Knowles H, et al. The Association of Name Recognition, Empathy Perception, and Satisfaction With Resident Physicians’ Care Amongst Patients in an Academic Emergency Department. J Clin Med Res. 2023;15(4):225-232. doi:10.14740/jocmr4901

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Walker LE, Colletti JE, Bellolio MF, Nestler DM. Progression of Emergency Medicine Resident Patient Experience Scores by Level of Training. J Patient Exp. 2019;6(3):210-215. doi:10.1177/2374373518798098

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Robinson RD, Dib S, Mclarty D, et al. Productivity, efficiency, and overall performance comparisons between attendings working solo versus attendings working with residents staffing models in an emergency department: A Large-Scale Retrospective Observational Study. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0228719. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0228719

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453-1457. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Emergency Medicine Milestones. 2nd rev. February 2021; implemented July 1, 2021. Chicago, IL: ACGME.

Emergency Medicine Milestones - Gabay G, Gere A, Zemel G, Moskowitz H. Personalized Communication with Patients at the Emergency Department-An Experimental Design Study. J Pers Med. 2022;12(10):1542. doi:10.3390/jpm12101542

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Gunalda J, Hosmer K, Hartman N, et al. Satisfaction Academy: A Novel Residency Curriculum to Improve the Patient Experience in the Emergency Department. MedEdPORTAL. 2018;14:10737. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10737

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Dalley MT, Baca MJ, Raza C, et al. Does a Standardized Discharge Communication Tool Improve Resident Performance and Overall Patient Satisfaction?. West J Emerg Med. 2020;22(1):52-59. doi:10.5811/westjem.2020.9.48604

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Nancy Buderer for her assistance in the statistical analysis for this project.

Funding

Not applicable

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

James Chan

Department of Emergency Medicine

Mercy Health St Rita’s Medical Center, United States

Email: james_chan@teamhealth.com

Co-Authors:

Tamer Yahya

Department of Emergency Medicine

Mercy Health St Rita’s Medical Center, United States

Matthew T Owens

(Chief Clinical Officer)

Mercy Health St Rita’s Medical Center, United States

Authors Contributions

Matthew T. Owens, MD, was not directly involved in the clinical care of the patient; however, he contributed to the development of this manuscript through academic input, organizational support, and refinement of the content. James Chan, MD; Tamer Yahya, MD; and Matthew T. Owens, MD were responsible for drafting the manuscript text, sourcing and editing clinical images, compiling investigation results, creating original diagrams and algorithms, and performing critical revisions for important intellectual content. All authors: James Chan, MD; Tamer Yahya, MD; and Matthew T. Owens, MD, reviewed and provided final approval of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Bon Secours Mercy Health (BSMH) IRB research participant protection program (RP³), IRB #57-LIM-GME-Chan, on October 24, 2023.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None

Guarantor

The guarantor accepts full responsibility for the finished work and the conduct of the study, had full access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish. The guarantor for this manuscript is James Chan, MD, PhD, RDMS.

DOI

Cite this Article

Chan J, Yahya T, Owens MT. Resident Physicians Led Patient Satisfaction Performance in a New Community-Based Emergency Medicine Residency Program. medtigo J Emerg Med. 2025;2(4):e3092246 doi:10.63096/medtigo3092246 Crossref