Author Affiliations

Abstract

Background: Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a serious clinical issue of the present age. It mostly affects women of reproductive age. Obesity is considered a potential risk factor associated with PCOS.

Objective: The goal of this review was to evaluate the prevalence of PCOS based on ranges of body mass index (BMI).

Methodology: All the suitable databases, such as Google Scholar, Springer, and PubMed, were searched for relevant articles. Definition of BMI was obtained from the World Health Organization (WHO) website. Articles published before 2021 were considered in this review. Only articles demonstrating the prevalence of PCOS with BMI and obesity were chosen, while others were excluded.

Conclusion: PCOS is positively correlated with BMI. The prevalence of PCOS tends to increase beyond a BMI of 25kg/m 2 test.

Keywords

Polycystic ovary syndrome, Body mass index, Obesity, Infertility, Insulin resistance.

Introduction

PCOS is a hormonal disorder marked by an imbalance of sex hormones that primarily affects women of reproductive age.[1,2] Signs and symptoms that are associated with PCOS include irregular menstrual cycle, polycystic ovaries, hirsutism, obesity, acne, hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance (Type 2 Diabetes), and infertility.[2,3] The majority of women with PCOS (38-88%) are either overweight or obese.[4,5] The level of obesity can be determined by using BMI. It is calculated by dividing the weight in kilograms by the square of the height in meters.[6] Adult BMI is classified into three categories: underweight (<18.5kg/m 2), normal weight (18.5kg/m 2 to 24.9kg/m 2), overweight (25kg/m 2 to 29.9kg/m 2), and obese (≥30kg/m 2).[7]

The etiology of PCOS has yet to be discovered, and there is no exact known cause at the moment. However, a genetic component as well as several additional risk factors, such as obesity and insulin resistance, have been identified.[8] In the current literature, there is a significant disparity in the BMI ranges associated with PCOS. Only a few researchers have investigated the relationship between BMI and PCOS. Due to variations with the diagnostic criteria for PCOS, these studies are frequently hampered by small sample sizes, selection bias, and are not comparable with the findings of other studies. The goal of this review is to evaluate the prevalence of PCOS based on ranges of BMI.

Methodology

All the suitable databases such as Google Scholar, Springer, and PubMed were searched for relevant articles. Definition of BMI was obtained from WHO website.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: Articles published before 2021 were considered in this review. Only articles demonstrating the prevalence of PCOS with BMI and obesity were chosen, while others were excluded.

Results

The percentage of PCOS patients is higher at BMI >25kg/m 2. i.e., it tends to increase beyond this value and decreases below this value (table 1).

| Author | Year | Country | Average BMI (kg/m2) | Prevalence of PCOS (%) |

| E. S. Knochenhauer et al[9] | 1998 | USA | 24.8 (white), 29.1 (black) | 4.6 |

| Diamanti-Kandarakis et al[10] | 1999 | Greece | 27.2 (group 1), 28.7 (group 2), 28.9 (group 3) | 6.8 |

| K. F. Michelmore et al[11] | 1999 | UK | 23.7 | 26 |

| Alvarez-Blasco et al[12] | 2006 | Spain | 34.8 | 6.5 |

| X. Chen et al[13] | 2008 | South China | 22.7 | 2.4 |

| Azziz et al[14] | 2008 | USA | 27.5 | 6.6 |

| Amini et al[15] | 2008 | Iran | 32.8 | 8.3 |

| March et al[16] | 2010 | South Australia | 25.7 | 17.8 |

| Tehrani et al[17] | 2011 | Iran | 26.2 | 8.5 |

| Teede et al[18] | 2013 | Australia | 27.8 | 5.8 |

| Joshi et al[19] | 2014 | India | 21.1 | 22.5 |

| Sharif et al[20] | 2016 | Qatar | 22.95 | 11.7 |

| Memon TF et al[21] | 2020 | Pakistan | 21.6 | 15.4 |

Table 1: Showing average BMI and prevalence of PCOS based on Rotterdam criteria

Discussion

PCOS is a major clinical issue of the present age that has been reported to affect 8%-13% of reproductive-aged women.[22] Obesity was first discovered to be a prevalent symptom of PCOS by Stein and Leventhal (1935) and later validated by many authors. Obesity has been estimated to affect up to 80% of PCOS women in the United States. According to a recent Spanish study, PCOS is five times more common in overweight or obese women of childbearing age (28.3%) as compared to the general population (5.5%).[23,24]

PCOS can appear at any time during a woman’s reproductive life; however, it is most common during adolescence.[25] The incidence rate of infertility in reproductive-age women begins to climb at a BMI of 24kg/m 2 and continues to increase as BMI rises.[26] According to a study published in June 2009, women with PCOS have reduced levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and increased levels of BMI as compared to normal women.[27]

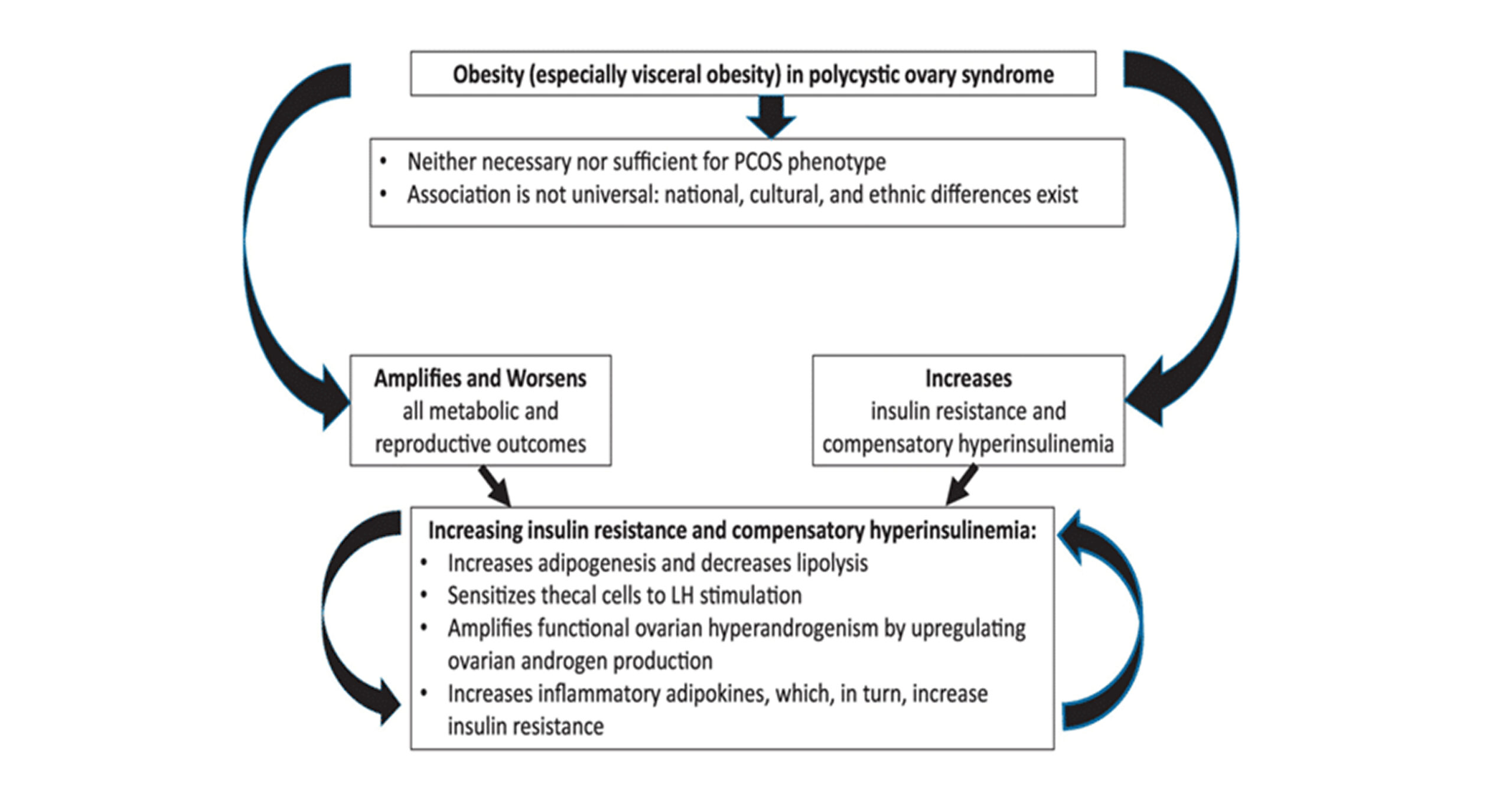

Association between obesity and PCOS: The most frequent finding in women with PCOS is obesity, and it is estimated that about 40%–80 % of women suffering from this condition are either overweight or obese.[28] A recent systematic review of 35 studies found that overweight (BMI 25–30kg/m 2) and obesity (BMI ≥30kg/m 2) were about 2 and 2.8 times more common in women with PCOS, respectively.[29] Obesity is linked to changes in adipokine and inflammatory cytokine production, which may contribute to obesity-related insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome.[30] In culture, hyper-insulinemia has been demonstrated to promote ovarian androgen synthesis by acting as a co-gonadotropin.[31] Patients with PCOS who have a BMI of 23kg/m 2 or more are more likely to develop metabolic disorders.[32] With increasing weight, the prevalence of dyslipidemia rises.[33] A similar association persists in the metabolic syndrome.[34] However, major multicenter research of women with PCOS reported no metabolic syndrome in those with PCOS and a BMI of 27kg/m 2 test.[35]

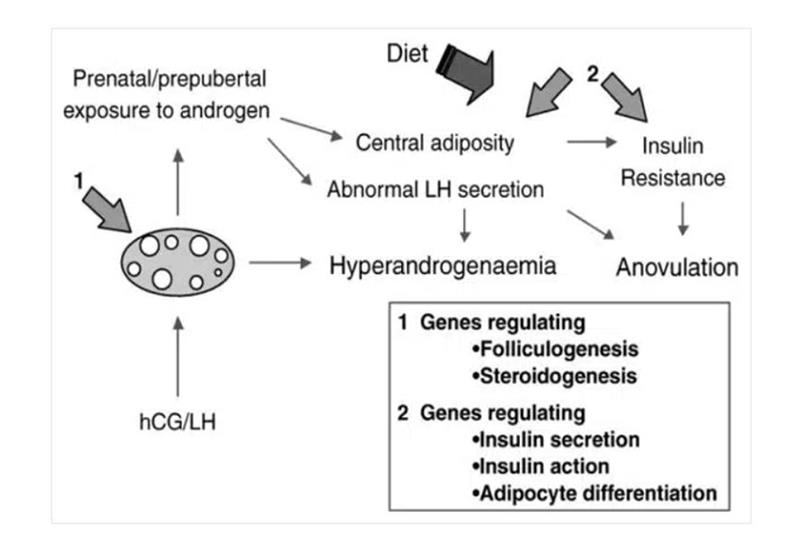

It’s unclear whether obesity causes PCOS or PCOS causes obesity. However, androgen exposure in postmenopausal women is the main cause of increasing visceral adiposity in obese as well as normal-weight women.[36] Similarly, a recent study suggests that uncontrolled obesity before puberty combined with severe insulin resistance can lead to the development of PCOS later in life (Figure 1).[37]

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the development of PCOS in women

Obesity is also associated with elevated testosterone concentrations, suggesting increased androgen production.[38] Aromatase is a protein found in adipose tissue that promotes the synthesis of bioactive estrogens from androgens, which are then released into the bloodstream.[39] This can also cause elevated estrone levels, which have been observed in PCOS women.[40] According to a study published in 2011, elevated BMI levels are less specific than lipid accumulation product (LAP) in predicting Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), confirming previous findings that LAP is better than BMI in predicting type 2 diabetes mellitus.[41-43]. This could be explained by the fact that an increase in BMI can be induced by an increase in lean mass or an enlargement of the protective subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) in the lower extremities.[44]

Figure 2: Showing the role of obesity in PCOS

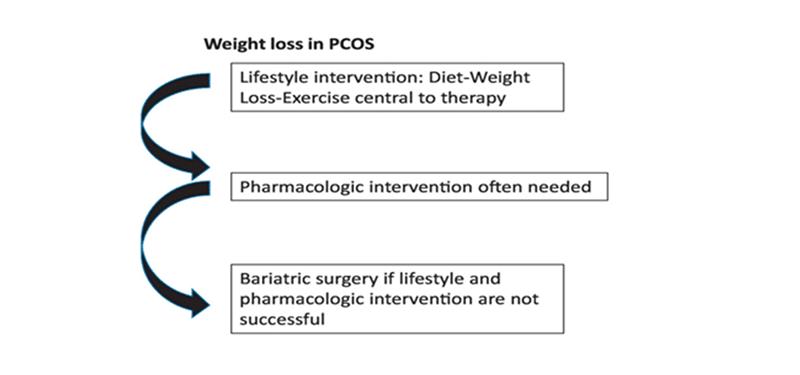

Figure 3: Showing treatment measures for PCOS

Limitations: While performing this review, we had to face many problems. Many of the articles were inaccessible. Moreover, there were only a few articles published on the selected topic.

Recommendations: Treating obesity might be useful to control PCOS. This includes lifestyle modifications like exercise, weight loss, healthy diet, etc. Besides this, pharmacologic treatment, such as metformin and bariatric surgery, remains a last resort and effective intervention. However, obesity is not a primary cause of PCOS, but rather a potential risk factor. So, further study is advised on the association of BMI with PCOS.

Conclusion

Our review suggests that there is a strong and positive relation between BMI and PCOS. The percentage of PCOS patients is higher at BMI >25kg/m 2test.

References

- Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Futterweit W, Glueck JS, Legro RS, Carmina E; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), American College of Endocrinology (ACE), Androgen Excess and PCOS Society (AES). American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society Disease State Clinical Review: Guide to the Best Practices in the Evaluation and Treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome–PART 1. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(11):1291-1300. doi:10.4158/EP15748.DSC PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Okoroh EM, Hooper WC, Atrash HK, Yusuf HR, Boulet SL. Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Among the Privately Insured, United States, 2003-2008. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(4):299.e1-299.e2997. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2012.07.023 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et al. Task Force on the Phenotype of the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome of The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society. The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society Criteria for the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: The Complete Task Force Report. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(2):456-488. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.06.035 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Legro RS. The Genetics of Obesity: Lessons for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;900:193-202. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06230.x Crossref | Google Scholar

- Balen AH, Conway GS, Kaltsas G, Techatrasak K, Manning PJ, West C, Jacobs HS. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: The Spectrum of the Disorder in 1741 Patients. Hum Reprod. 1995;10(8):2107-2111. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136243 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Broekmans FJ, Knauff EA, Valkenburg O, Laven JS, Eijkemans MJ, Fauser BC. PCOS According to the Rotterdam Consensus Criteria: Change in Prevalence Among WHO-II Anovulation and Association with Metabolic Factors. BJOG. 2006;113(10):1210-1217. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01008.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- World Health Organization. Surveillance of Chronic Disease Risk Factors: Country Level Data and Comparable Estimates Surveillance of Chronic Disease Risk Factors: Country Level Data and Comparable Estimates

- Carmina E. Diagnosis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: From NIH Criteria to ESHRE-ASRM Guidelines. Minerva Ginecol. 2004;56(1):1-6 PubMed | Google Scholar

- Knochenhauer ES, Key TJ, Kahsar-Miller M, Waggoner W, Boots LR, Azziz R. Prevalence of the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Unselected Black and White Women of the Southeastern United States: A Prospective Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(9):3078-3082. doi:10.1210/jcem.83.9.5090 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Kouli CR, Bergiele AT, et al. A Survey of the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in the Greek Island of Lesbos: Hormonal and Metabolic Profile. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(11):4006-4011. doi:10.1210/jcem.84.11.6148 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Michelmore KF, Balen AH, Dunger DB, Vessey MP. Polycystic ovaries and associated clinical and biochemical features in young women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1999;51(6):779-786. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00886.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholarv

- Alvarez-Blasco F, Botella-Carretero JI, San Millán JL, Escobar-Morreale HF. Prevalence and characteristics of the polycystic ovary syndrome in overweight and obese women. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(19):2081-2086. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.19.2081 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Chen X, Yang D, Mo Y, Li L, Chen Y, Huang Y. Prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in unselected women from southern China. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;139(1):59-64. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.12.018 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, Key TJ, Knochenhauer ES, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2745-2749. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-032046 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Amini M, Horri N, Farmani M, et al. Prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in reproductive-aged women with type 2 diabetes. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2008;24(8):423-427. doi:10.1080/09513590802306143 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- March WA, Moore VM, Willson KJ, Phillips DIW, Norman RJ, Davies MJ. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(2):544-551. doi:10.1093/humrep/dep399 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ramezani Tehrani F, Simbar M, Tohidi M, Hosseinpanah F, Azizi F. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample of Iranian population: Iranian PCOS prevalence study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2011;9:39. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-9-39 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Teede HJ, Joham AE, Paul E, Moran LJ, Loxton D, Jolley D, Lombard C. Longitudinal weight gain in women identified with polycystic ovary syndrome: results of an observational study in young women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21(8):1526-1532. doi:10.1002/oby.20213 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Joshi B, Mukherjee S, Patil A, Purandare A, Chauhan S, Vaidya R. A cross-sectional study of polycystic ovarian syndrome among adolescent and young girls in Mumbai, India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18(3):317-324. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.131162 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sharif E, Rahman S, Zia Y, Rizk NM. The frequency of polycystic ovary syndrome in young reproductive females in Qatar. Int J Womens Health. 2016;9:1-10. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S120027 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Memon TF, Channar M, Shah SAW, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome: risk factors and associated features among university students in Pakistan. JPUMHS. 2020;10(1):22-29. Polycystic ovary syndrome: risk factors and associated features among university students in Pakistan

- Azziz R, Carmina E, Chen Z, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16057. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.57 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Dunaif A. Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome revisited: an update on mechanisms and implications. Endocr Rev. 2012;33(6):981-1030. doi:10.1210/er.2011-1034 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Alvarez-Blasco F, Botella-Carretero JI, San Millán JL, Escobar-Morreale HF. Prevalence and characteristics of the polycystic ovary syndrome in overweight and obese women. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(19):2081-2086. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.19.2081 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Barber TM, Franks S. Obesity and polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2021;95(4):531-541. doi:10.1111/cen.14421 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rich-Edwards JW, Spiegelman D, Garland M, et al. Physical activity, body mass index, and ovulatory disorder infertility. Epidemiology. 2002;13(2):184-190. doi:10.1097/00001648-200203000-00013 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Beydoun HA, Stadtmauer L, Beydoun MA, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome, body mass index and outcomes of assisted reproductive technologies. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009;18(6):856-863. doi:10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60037-5 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Vague J. The degree of masculine differentiation of obesities: a factor determining predisposition to diabetes, atherosclerosis, gout, and uric calculous disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 1956;4(1):20-34. doi:10.1093/ajcn/4.1.20 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lim SS, Davies MJ, Norman RJ, et al. Overweight, obesity and central obesity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2012;18(6):618-637. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms030 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- DeBoer MD. Obesity, systemic inflammation, and increased risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes among adolescents: a need for screening tools to target interventions. Nutrition. 2013;29(2):379-386. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2012.07.003 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Willis D, Franks S. Insulin action in human granulosa cells from normal and polycystic ovaries is mediated by the insulin receptor and not the type-I insulin-like growth factor receptor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(12):3788-3790. doi:10.1210/jcem.80.12.8530637 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Chen X, Ni R, Mo Y, et al. Appropriate BMI levels for PCOS patients in Southern China. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(5):1295-1302. doi:10.1093/humrep/deq028 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wild RA, Carmina E, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, et al. Assessment of cardiovascular risk and prevention of cardiovascular disease in women with the polycystic ovary syndrome: a consensus statement by the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (AE-PCOS) Society. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(5):2038-2049. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-2724 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ehrmann DA, Liljenquist DR, Kasza K, et al; PCOS/Troglitazone Study Group. Prevalence and predictors of the metabolic syndrome in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(1):48-53. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-1329 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rosenfield RL. Ovarian and adrenal function in polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1999;28(2):265-293. doi:10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70070-0 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Littlejohn EE, Weiss RE, Deplewski D, et al. Intractable early childhood obesity as the initial sign of insulin resistant hyperinsulinism and precursor of polycystic ovary syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2007;20(1):41-51. doi:10.1515/jpem.2007.20.1.41 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rosenfield RL. Clinical review: Identifying children at risk for polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(3):787-796. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-2012 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kaplowitz PB, Slora EJ, Wasserman RC, et al. Earlier onset of puberty in girls: relation to increased body mass index and race. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):347-353. doi:10.1542/peds.108.2.347 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lobo RA, Granger L, Goebelsmann U, et al. Elevations in unbound serum estradiol as a possible mechanism for inappropriate gonadotropin secretion in women with PCO. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1981;52(1):156-158. doi:10.1210/jcem-52-1-156 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wehr E, Gruber HJ, Giuliani A, et al. The lipid accumulation product is associated with impaired glucose tolerance in PCOS women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(6):E986-E990. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-0031 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kahn H. The “lipid accumulation product” performs better than the body mass index for recognizing cardiovascular risk: A population-based comparison. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2005;5:26. doi:10.1186/1471-2261-5-26 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kahn HS. The lipid accumulation product is better than BMI for identifying diabetes: a population-based comparison. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(1):151-153. doi:10.2337/diacare.29.1.151 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Van Pelt RE, Evans EM, Schechtman KB, et al. Waist circumference vs body mass index for prediction of disease risk in postmenopausal women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(8):1183-1188. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0801640 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Glueck CJ, Goldenberg N. Characteristics of obesity in polycystic ovary syndrome: etiology, treatment, and genetics. Metabolism. 2019;92:108-120. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2018.11.002 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

Not reported

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Mubashir Ali

Department of Radiological Sciences and Medical Imaging

University of Lahore, University Institute of Radiological Sciences and Medical Imaging, Lahore, Pakistan

Email: mubimine123@gmail.com

Co-Author:

Syed Zaigham Ali Sha

Department of Chief Radiology Technologist

Human resource development center (HRDC), Skardu, Pakistan

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest Statement

Not reported

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Mubashir A, Syed ZAS. Ranges of Body Mass Index in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Maximum and Minimum. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622438. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622438 Crossref