Author Affiliations

Abstract

Background: All over the world, workplace violence (WPV) among healthcare professionals, especially nurses, is increasing at an alarming rate. Because they have little clinical experience and weak coping strategies, nursing students are particularly at risk. Many schools use simulation training to help students learn how to react to serious situations. This study aimed to assess the perceptions and effectiveness of simulation-based training in preparing nursing students to handle workplace violence in both public and private nursing colleges in Swat.

Methodology: This study used stratified random sampling and took on a descriptive, cross-sectional form. From a group of 1,200 potential participants, 320 first-year nursing students were chosen by using the Raosoft sample size calculator. Data collection used a structured and validated questionnaire, and these data were analyzed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27. We analyzed the results by using descriptive statistics, mean scores, and Pearson’s correlation.

Results: Only those who had taken part in one WPV simulation session were allowed to participate. The majority (82.5%) thought the scenarios were realistic, 77.8% felt more prepared emotionally, and 80.6% were more confident dealing with WPV. Results showed a strong relationship between simulation experience and both confidence in being ready (r = 0.614, p < 0.001) and emotional confidence (r = 0.538, p < 0.001), but no relationship with perceived effectiveness (r = 0.162, p = 1.000).

Conclusion: Learning through simulation helps nursing students better respond to situations involving WPV. The nursing curriculum should strongly include information on this topic.

Keywords

Workplace violence, Simulation-based training, Nursing students, Emotional preparedness, Clinical education.

Introduction

Workplace violence in healthcare is a major issue globally, mainly because nurses communicate easily with patients and their families every day. Workplace violence refers to any type of threatening, disruptive behavior, including harassment or violence at your workplace.[1] It may consist of yelling insults, physical beatings, and, on rare occasions, murder. Simulation-based training is about giving learners the chance to respond to situations similar to those in real life, thanks to the presence of mankind, actors, or virtual space.[2] Many nursing classes now include this method to help students improve at decision-making, talking with others, and resolving crises. A growing number of researchers are interested in how nursing students feel about this type of training, whether it prepares them, and how real and connected they feel to what they learn.[3]

WPV is now a major problem in healthcare among nurses and other staff. The World Health Organization (WHO) says that as many as 38% of health workers all over the world have faced physical abuse, while almost all report experiencing verbal abuse.[4] In Pakistan and other low- and middle-income countries, the situation is made worse by a lack of protocols, not having enough staff, and inadequate preparation for dealing with aggression.[5] Students in nursing, while they learn in the classroom and then in the clinic, are specifically at risk. Being exposed to WPV is dangerous for their health and may prevent them from advancing or staying in their jobs.[6]

A number of nursing students report that they lack the skills needed to deal with hostile situations in their practice. There are not many formal and practical parts in traditional nursing programs devoted to working with WPV. Therefore, students might act unsuitably or hesitate in tough moments, which may increase conflict or create strong feelings of tension. Having students practice security skills in a simulated environment bridges this gap by showing them how to keep themselves safe, talk with experts, and calm dangerous situations.[7,8]

Simulation has become more important in nursing over the past two decades, mainly to support skill development in clinical settings. Still, using ERPs to train people in behavior and safety, for example, with WPV, is still developing.[9] Instead of fitting into a lecture format, simulation makes participants feel involved in serious situations where they must use their brains and have confidence.[10] In developed nations, WPV training that uses simulations has been shown to enhance students’ awareness of their surroundings, their conversations with aggressive people, and their total readiness. Therefore, these outcomes suggest that using these tools may become more widespread in nursing programs that treat WPV areas.[11]

In Pakistan, several cases of workplace violence in hospitals have occurred, often in medical emergencies, psychiatric departments, and when notifying patients’ families about death. Nevertheless, there is not much proof showing how ready nursing students are for such situations. Many institutions provide guidance, although it is not reliably put into practice or taught in undergraduate nursing. Also, respect for authority and issues related to gender may play a role in the way WPV happens and how it is managed. It is important to learn what students think about using simulation for WPV training.[12,13]

Simulation is especially useful in helping to improve soft skills, like empathy, being assertive, and resolving conflicts, for work in the field of WPV.[14] Learning the principles of communication and safety may come easily, but students only gain practice by actually using them. Simulation activities provide several chances for adults to experience, receive help, and reflect on what they are learning.[15] Both engaging students’ minds and emotions in simulations can promote behavior change and make them better prepared for clinical practice.[16]

In short, security and career growth at work remain key challenges for nursing students. Simulation training is useful because it offers real-life chances to practice managing violent situations. Learning how nursing students feel about such training and how useful it is for real nursing jobs is vital for enhancing nursing education. The goal of this study is to see what others think and experience about these topics so that new curricula can be made and nurses are prepared to handle real practice with confidence.

Methodology

We used descriptive statistics combined with direct observations to analyze the views of nursing students regarding simulations before and after facing workplace violence. Because of this design, the research team could gather clear data from numerous students and observe common trends, related links, and patterns concerning their experiences and ratings of simulation-based WPV training. We carried out this study at both public and private nursing colleges in the Swat, Pakistan, region. So that different nursing students could participate, these institutions were chosen to cover a wide range of schools and income groups. There were 1,200 nursing students in both diploma and basic nursing programs who were included in this survey, according to the institution’s records.

A Raosoft sample size calculator was used to find the ideal sample size at a confidence level of 95%, a margin of error of 5%, and an expected response distribution of 50%. To reach these parameters, researchers found that a sample of 291 participants would be needed. So as to ensure data wasn’t missing and the sample was complete, the final number needed was increased by 10 percent, which resulted in a sample of 320 people.

It was important to ensure satisfactory participation by both public and private nursing schools, so we used stratified random sampling. Representatives of eligible students were chosen by selecting participants randomly within each of the strata provided by the academic offices. To join the study, participants had to attend at least one simulation class on workplace violence, be registered in a SWAT nursing program, and give written informed consent. Those who had not yet participated in simulation sessions or were on leave from their studies were left out of the study.

Data collection procedure: We used a questionnaire designed for this Particular study to collect the required data. It was created as a survey with three parts: (1) demographic details, (2) opinions about the simulation software’s realism, how it made them feel, and how it helps, and (3) assessments of effectiveness in conferring confidence and skills for WPV readiness. A panel of experts in nursing education and simulation training reviewed the questionnaire, which was adapted from previous research, to ensure that it was valid. First, 30 students who were not part of the final sample were included in a pilot test, and the results suggested that the tool has high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86.

For two weeks, data collection was carried out with students at each of the colleges. Once the heads of the institutions and the review boards approved, trained students passed out questionnaires to selected students during their lessons. Everyone involved was free to choose, and the group’s confidentiality was never broken. All those who participated signed an informed consent form, after which they filled out the survey.

Data analysis procedure: The data were arranged and fed into SPSS version 27 to be analyzed. Frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations were applied to summarize both demographic variables and important features. To study how helpful simulation exposure was in improving views on dealing with WPV, Pearson’s correlation was used. In all cases, a significant level of p < 0.05 was used to run statistical tests.

Results

Of the 320 students in the study, 61.9% were male and 38.1% were female. The largest group (45.6%) was in the age group 21–23, with those 18–20 years second-most, 41.3%, and 13.1% were 24 years or older. Nearly three-quarters (71.2%) of students at those colleges went to private schools, with 28.8% enrolling in public colleges. There is a mix of gender, age groups, and types of institutions in this distribution. Because the sample is so varied, the study’s conclusions can be applied to more members of the population (Table 1).

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | Male | 198 | 61.9% |

| Female | 122 | 38.1% | |

| Age group | 18–20 years | 132 | 41.3% |

| 21–23 years | 146 | 45.6% | |

| 24 years and above | 42 | 13.1% | |

| Institution type | Public | 92 | 28.8% |

| Private | 228 | 71.2% |

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of participants

All 320 of the participants (100%) had joined a workplace violence (WPV) simulation session. A high number (82.5%) mentioned that the simulations appeared genuine and involved, and 77.8% thought that experiencing them improved their emotional preparedness. Furthermore, 86.9% felt that the simulation reflected actual hospital situations. Among the participants, 63.4% stated the importance of simulation-based training rather than learning only from theory. (Table 2)

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Attended at least one WPV simulation session | 320 | 100% |

| Found the simulation realistic and engaging | 264 | 82.5% |

| Reported increased emotional readiness | 249 | 77.8% |

| Found a simulation relevant to clinical settings | 278 | 86.9% |

| Preferred simulation over theoretical learning | 203 | 63.4% |

Table 2: Simulation training experience and perception

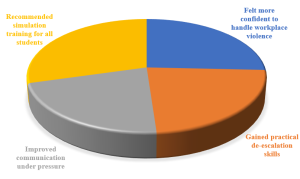

According to the study, 80.6% of participants believed they would better handle workplace violence after participating in the simulation training. Roughly 72.5% learned to handle situations by de-escalation, compared to 68.1% who improved the way they communicate under pressure. More than 92% of the group recommended that nursing students should have access to simulation training. The results indicate that simulation is considered effective in getting students ready for real-life problems (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Effectiveness of simulation-based WPV training

Students agreed on the accurate appearance of the simulation, with an average score of 4.12 (±0.52). Students rated emotional preparedness 4.08 (±0.49), implying that they experienced greater emotional readiness after the simulation. While students said the training helped with developing skills, the mean was just above moderate at 3.89 (±0.58), indicating that further improvements could be made (Table 3).

| Domain | Mean score | Standard deviation (SD) | Interpretation |

| Perception of simulation realism | 4.12 | ±0.52 | High |

| Emotional preparedness score | 4.08 | ±0.49 | High |

| Effectiveness in skill development | 3.89 | ±0.58 | Moderate to high |

Table 3: Mean perception and effectiveness scores

Correlation analysis discovered that simulation exposure was strongly linked with participants’ sense of being prepared to deal with violence (r = 0.614, p < 0.001), meaning that more simulation exposure helped students feel more prepared. Furthermore, a significant relationship was observed between simulation use and emotional confidence (r = 0.538, p < 0.001), meaning that simulation helps students become better equipped to handle difficult situations. Both results were found to be significant, demonstrating that simulation training works (Table 4).

| Variables | r-value | p-value | Interpretation |

| Simulation exposure & perceived readiness | 0.614 | < 0.001 | Strong positive correlation |

| Simulation exposure & emotional confidence | 0.538 | < 0.001 | Moderate to strong correlation |

Table 4: Correlation between simulation exposure and WPV preparedness

Discussion

The results suggest that simulated learning prepares future nurses well to respond to WPV challenges. Most people who took part said the simulations felt real, made them care, and were useful for their future work as clinicians. Outcomes are confirmed by findings reported showing that experience with simulation training in immersive environments gave nursing students greater confidence and skills when having an encounter with a difficult patient.[17] In the same way, the study’s high mean ratings for realism and emotional preparedness are consistent with the study that highlighted the importance of strong feelings in simulation to encourage thinking about learning and preparation.[18]

This study’s results refute earlier criticism that simulation sessions lacked depth or failed to reflect real-life stresses, suggesting that powerful sessions are possible. Since most students found the sessions to be accurate and said their emotional readiness increased, it seems that investments in simulation design have improved on past issues. Besides improving their techniques, these findings show that students experience emotional benefits from using simulation.[19]

Results confirm that more time spent in simulation environments helped students handle stressful situations in a better way. Correlation coefficients (0.614 for readiness and 0.538 for emotional confidence) in the current study suggest that the amount and nature of exposure to new situations can prepare students for real life. Active actions needed during simulation, unlike learning from a book or video, reflect how every incident in the real world can be different and let students train their skills to de-escalate quickly and safely.[20]

Although the majority (80.6%) of students believed WPV confidence grew, only 68.1% registered improvements in speaking and acting under stress. Unlike the study, in which improvement scores exceeded 80%, we had some results lower than that. Variations in the way communication elements are highlighted in post-session meetings and culture-based views on communication self-perception may play a role. The results indicate that simulation helps a lot in various skills, but by improving training design in communication areas, learners could improve still further.[5,21]

It’s remarkable that more than three out of five students now prefer simulation learning over classes that use theory. This matches the findings of the study, which encouraged including experiential learning in nursing education. Still, a few students may see value in theory as a basis, which implies that mixing the two approaches is the best way. Making theory an important aspect of simulation through reflecting together and talking afterwards could help close this gap and lead to better learning.[22]

When almost every educator says simulation training should be common for nursing students, this underlines how key experiential learning is within the curriculum. Furthermore, the World Health Organization promotes worldwide efforts to teach WPV preparedness in nursing courses. It is important to observe that people working for private firms were more likely to use simulation because they often have better access to these facilities, which may have led to generally favorable results in our study. It makes us think about how fair it is for some students to have more access to training than others and how simulation experiences might be more standardized.[23]

The findings show that using simulation exercises supports the growth of nursing students’ skills and feelings toward handling WPV. Even though the results match those from other countries, they also point out that communication training could be improved. Such findings may support future updates in nursing curriculum and policies to construct a solid base for new nurses facing complications at work.

Recommendations

All nursing colleges must ensure they have enough simulation facilities, so there are no differences in student preparation. Educators need training to help them use simulations effectively, and therefore, such programs should be offered. It would be useful for future investigations to follow up on how rapidly learned skills from simulation are used in different clinical scenarios and during the start of one’s career. When students learn through real-life experiences, nursing schools can better meet the challenge of violence from coworkers and patients.

Conclusion

Researchers found that simulation-based learning is an approved and successful way to prepare nursing students for dealing with workplace violence. Most participants indicated that the simulations were genuine, fully engaged in their emotions, and helped them practice communicating, de-escalating situations, and boosting their confidence. It is clear from the data that more simulation time greatly improves students’ confidence and skills. These results stress that simulation is important for both technical skills and personal readiness for challenges ahead.

Since many participants find WPV training highly helpful and satisfying, it is suggested that simulation exercises become a formal part of nursing education at all levels. Repeated simulation sessions, together with reflective debriefings, should be made a priority to help people learn more. Modules should pay more attention to stressful communication to help people improve their results.

References

- Zhang J, Zheng J, Cai Y, Zheng K, Liu X. Nurses’ experiences and support needs following workplace violence: A qualitative systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(1-2):28-43. doi:10.1111/jocn.15492 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Yesilbas H, Baykal U. Causes of workplace violence against nurses from patients and their relatives: A qualitative study. Appl Nurs Res. 2021;62:151490. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2021.151490 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lundell Rudberg S. Feeling Ready and Always More to Learn: Students’ Journeys Towards Becoming a Professional Nurse. Dissertation. Karolinska Institute; 2023. Feeling Ready and Always More to Learn: Students’ Journeys Towards Becoming a Professional Nurse

- Ghareeb NS, El-Shafei DA, Eladl AM. Workplace violence among healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic in a Jordanian governmental hospital: the tip of the iceberg. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021;28(43):61441-61449. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-15112-w PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bhatti OA, Rauf H, Aziz N, Martins RS, Khan JA. Violence against Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of Incidents from a Lower-Middle-Income Country. Ann Glob Health. 2021;87(1):41. doi:10.5334/aogh.3203 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Naseem M, Shahil Feroz A, Arshad H, et al. Perceptions, challenges and experiences of frontline healthcare providers in Emergency Departments regarding Workplace Violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: A protocol for an exploratory qualitative study from an LMIC. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2):e055788. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055788 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mitchell B. Undergraduate Paramedic Student Experience with Workplace Violence, Whilst on Clinical Placement. Dissertation. Flinders University, College of Medicine & Public Health; 2021. Undergraduate Paramedic Student Experience with Workplace Violence Whilst on Clinical Placement

- Bragg A. Development of a Workplace Violence Education Huddle Program and facilitator’s manual. Degree thesis. Memorial University; 2021. Development of a Workplace Violence Education Huddle Program and facilitator’s manual

- Wijaya M. A decade of ERP teaching practice: a systematic literature review. Educ Inf Technol. 2023;28:1-21. doi:10.1007/s10639-023-11753-1 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ragsdale M, Schuessler JB. An integrative review of simulation, senior practicum and readiness for practice. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;55:103087. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103087 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hasebrook JP, Michalak L, Kohnen D, et al. Digital transition in rural emergency medicine: Impact of job satisfaction and workload on communication and technology acceptance. PLoS One. 2023;18(1):e0280956. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0280956 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bhatti OA, Rauf H, Aziz N, Martins RS, Khan JA. Violence against Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of Incidents from a Lower-Middle-Income Country. Ann Glob Health. 2021;87(1):41. doi:10.5334/aogh.3203 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hsu MC, Chou MH, Ouyang WC. Dilemmas and Repercussions of Workplace Violence against Emergency Nurses: A Qualitative Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(5):2661. doi:10.3390/ijerph19052661 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Elendu C, Amaechi DC, Okatta AU, et al. The impact of simulation-based training in medical education: A review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103(27):e38813. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000038813 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wang Y, Ji Y. How do they learn: types and characteristics of medical and healthcare student engagement in a simulation-based learning environment. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):420. doi:10.1186/s12909-021-02858-7 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Altmiller G, Pepe LH. Influence of Technology in Supporting Quality and Safety in Nursing Education. Nurs Clin North Am. 2022;57(4):551-562. doi:10.1016/j.cnur.2022.06.005 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ropponen P, Tomietto M, Pramila-Savukoski S, et al. Impacts of VR simulation on nursing students’ competence, confidence, and satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Nurse Educ Today. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2025.106756 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Madsgaard A, Røykenes K, Smith-Strøm H, Kvernenes M. The affective component of learning in simulation-based education – facilitators’ strategies to establish psychological safety and accommodate nursing students’ emotions. BMC Nurs. 2022;21(1):91. doi:10.1186/s12912-022-00869-3 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Tjønnås MS, Das A, Våpenstad C, Ose SO. Simulation-based skills training: a qualitative interview study exploring surgical trainees’ experience of stress. Adv Simul (Lond). 2022;7(1):33. doi:10.1186/s41077-022-00231-2 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Elendu C, Amaechi DC, Okatta AU, et al. The impact of simulation-based training in medical education: A review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103(27):e38813. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000038813 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Jackson D, Dean B. The contribution of different types of work-integrated learning to graduate employability. High Educ Res Dev. 2022;42:1-18. doi:10.1080/07294360.2022.2048638 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Asad MM, Naz A, Churi P, Tahanzadeh MM. Virtual reality as pedagogical tool to enhance experiential learning: A systematic literature review. Educ Res Int. 2021;2021:7061623. doi:10.1155/2021/7061623 Crossref | Google Scholar

- World Health Organization. Addressing Violence Against Women in Pre-Service Health Training: Integrating Content from the Caring for Women Subjected to Violence Curriculum. 2022. Addressing Violence Against Women in Pre-Service Health Training: Integrating Content from the Caring for Women Subjected to Violence Curriculum

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Dr. Shah Hussain, Principal/Assistant Professor, Zalan College of Nursing, Swat, for his invaluable supervision, guidance, and support throughout the course of this study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Najam Ul Sabha

Department of Nursing

Dr. Faisal Masood Teaching Hospital, Sargodha, Pakistan

Email: najamulsabah@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Firdos Kausar

Department of Nursing

Sharif College of Nursing, Lahore, Pakistan

Tamsila Sanam

Department of Nursing

Saida Waheed FMH College of Nursing, Lahore, Pakistan

Nageena Bibi

Department of Nursing

Midwest Institute of Sciences, Islamabad, Pakistan

Shah Hussain

Department of Nursing

Zalan College of Nursing, Swat, Pakistan

Authors Contributions

Firdos Kausar contributed to the collection and analysis of data. Najam Ul Sabha was responsible for collecting and organizing the data, as well as interpreting the findings. Tamsila Sanam and Nageena Bibi were engaged in both data collection and its subsequent analysis. Shah Hussain focused on analyzing the data and interpreting the results.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from Pak-Swiss Nursing College, Swat (Ref. No. PSNC/IRB/25/12).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Guarantor

Firdos Kausar is the guarantor of this study and takes full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data analysis.

DOI

Cite this Article

Kausar F, Ul Sabha N, Sanam T, Bibi N, Hussain S. Perception and Effectiveness of Simulation-Based Training in Preparing Nursing Students to Handle Workplace Violence. medtigo J Med. 2025;3(2):e30623222. doi:10.63096/medtigo30623222 Crossref