Author Affiliations

Abstract

Background: This case report highlights a rare but serious presentation of mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) in conjunction with a rare fungus found after ordering a chest computed tomography (CT) for the purposes of lung cancer screening.

Case presentation: The patient presented without any symptoms or physical exam findings for lung cancer screening and was found to have a large mass lesion of the lung with central cavitation with pathology confirming diagnosis of MAC infection with rare fungal hyphae.

Conclusions: Physicians should continue to perform preventive screening for lung cancer in those who have a 20 pack-year or more smoking history, and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years, and are between the ages of 50-80 years old, and maintain a high index of suspicion for uncommon presentations. The use of surgical pathology can serve as a diagnostic tool when determining treatment plans for individuals with infectious disease findings.

Keywords

Mycobacterium avium complex, Lung cancer screening, Rare fungal hyphae, Pulmonary diagnosis, Infections.

Introduction

MAC infection could present in conjunction with rare fungal hyphae, with little to no symptoms in those who have weakened immune systems or lung conditions.[1] MAC infection is present in soil and water and has had increased prevalence in non-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) individuals.[1,2] MAC infection can become serious and damage the lungs, and common presentations include fatigue, chronic cough, shortness of breath, night sweats, hemoptysis, and weight loss; however, many patients also present with little to no symptoms.[3] MAC infection has increased in prevalence. Therefore, it is important for early detection and the use of pathology tools to develop appropriate treatment plans.[4] Here we present a unique case of MAC infection with a rare fungus that presented for a routine physical exam.

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old immunocompetent male with a past medical history significant for hypertension (on lisinopril 20 mg daily), controlled type 2 diabetes (on sitagliptin 100 mg daily, glipizide 10 mg twice a day, and Jardiance 12.5 mg-metformin 1000 mg combination pill twice a day), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (on albuterol, fluticasone propionate-salmeterol and tiotropium inhalers), and tobacco use disorder with a 30-pack year smoking history presented for a routine physical exam. Review of systems was within normal limits. On physical examination, his lungs were clear to auscultation and percussion without any wheezing or gallops. He did not have any remarkable head, ear, nose, throat, cardiac, gastrointestinal, neurological, or musculoskeletal findings. He had a low-dose chest CT performed for the purposes of lung cancer screening, which was significant for a large mass lesion with central cavitation in the posterior left lung apex measuring 4.5 cm, increased in size from previous, with mild adjacent surrounding inflammatory bronchiolitis also in the left lung apex.

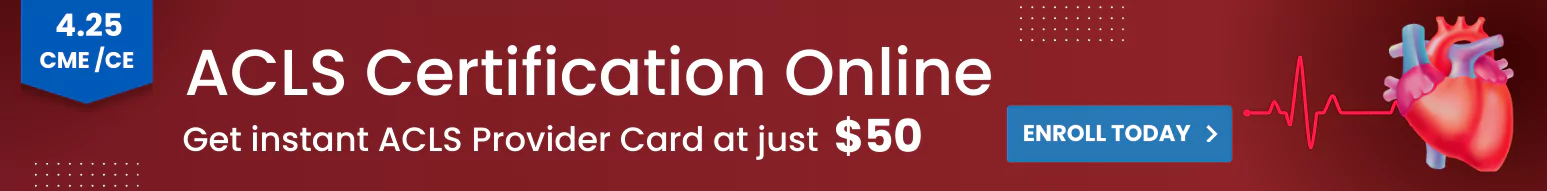

Figure 1: a) T2-weighted axial image with a large mass lesion with central cavitation in the posterior left lung ape

b) T2-weighted coronal image with a large mass lesion with central cavitation in the posterior left lung apex

He also had a positron emission tomography (PET)-CT, which was significant for a left apical lung mass with central cavitation despite lack of flurodeoxyglucose (FDG) avidity, suspicious for primary pulmonary malignancy without any anatomic/metabolic, mediastinal/thoracic adenopathy or widespread metastatic disease.

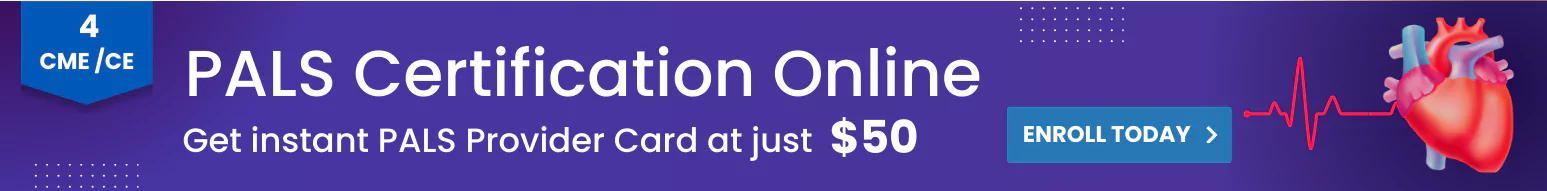

Figure 2: 4.0 x 3.2 cm left apical lung mass with central cavitation, with lack of FDG avidity

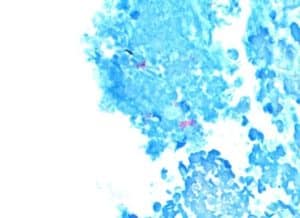

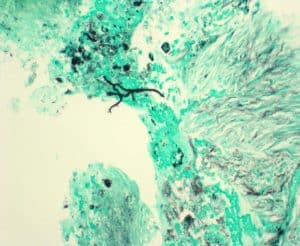

The patient had an unintentional 16 lb weight loss over the past year. A referral to pulmonology was made, and the patient had an endobronchial ultrasound-guided biopsy completed. Three days after his biopsy, he presented to the emergency room with complaints of chest pain, vitals otherwise normal, and was found to have a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction requiring balloon angioplasty and stent placement to the left anterior descending artery. While in the hospital, infectious disease was consulted given left lung mass and biopsy findings showing chronic inflammation, extensive necrosis, gram stain positive for rare fungal hyphae, positive acid-fast bacilli (AFB), without any evidence of malignancy.

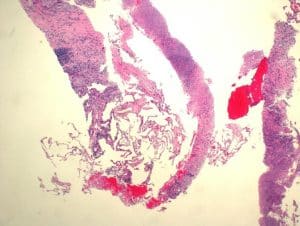

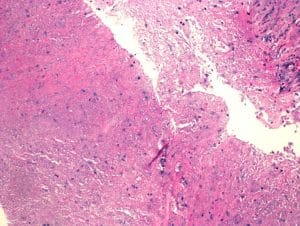

Figure 3: Hematoxylin and eosin stain of residual benign lung alveolar tissue and surrounding fibrous stroma with chronic inflammation and extensive necrosis with no evidence of malignancy seen (10x, scale bar 500 lm)

Figure 4: Extensive necrosis with no residual epithelium in this field. (5x, scale bar 500 lm)

Figure 5: AFB stain shows focal area with aggregated pink rods showing AFB (10x, scale bar 500 lm)

Figure 6: GMS stain for fungi shows a single small aggregate of rare fungal hyphae (20x, scale bar 500 lm)

Case Management

At the time, he was put on voriconazole 200 mg twice a day for 3 months for presumed aspergillosis. The patient then presented outpatient for emergency room follow-up with infectious disease, where he reported he was not able to tolerate voriconazole. At the time, he was re-diagnosed with a rare fungus and MAC and placed on azithromycin 250 mg once a day, rifampin 600 mg once a day, and ethambutol 1000 mg daily with a plan to follow up with an outpatient with infectious disease (ID) in 5 weeks.

Discussion

Physicians should be aware of infrequent presentations of MAC with rare fungus in those patients who are immunocompromised or have predisposing lung conditions. Some reports document MAC infection disease activity suppression after fungal infection due to an increase in β-D-glucan, possibly from microbial substitution.[5] A delay in diagnosis could be detrimental to the patient and may lead to life-threatening dissemination and sepsis. MAC lung disease symptoms are often nonspecific and can therefore cause a delay in diagnosis. Our patient had extensive necrosis along with the cavitated mass, which was treated with antibiotics. Systemic reviews have found the 5-year mortality rate for MAC infection to be greater than 25%, therefore prompt diagnosis and effective management if necessary.[6] Research also supports early clarification of pathogens, and the use of bronchoscopic alveolar lavage fluid examination and macro genomic next-generation sequencing has high specificity in identifying infectious disease pathogens in pulmonary cases.[4] The patient’s history of tobacco use disorder and COPD likely contributed to the development of this complication. The CT scan findings of the large mass lesion with central cavitation, combined with the pathology report with positive AFB, rare fungal hyphae, and extensive necrosis, were significant in diagnosing the condition. Treatment usually consists of conservative management, airway clearance, antibiotics, or surgical resection.[7]

Conclusion

It is essential to recognize uncommon presentations of MAC lung infection in outpatient and inpatient settings, pre-disposed patients with weakened immune systems or underlying lung disease, and to provide prompt treatment. Research should continue to improve patient outcomes and develop rapid testing, definitive biomarkers, and more tolerable treatment regimens.[8] The use of histology can help identify causes of infectious presentations and allow for early management.

References

- Faria S, Joao I, Jordao L. General overview on nontuberculous mycobacteria, biofilms, and human infection. J Pathog. 2015;2015:809014. doi.10.1155/2015/809014 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(4):367-416. doi.10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- American Lung Association. MAC lung disease. MAC Lung Disease

- Ji HL, Li XR, Luo JF, et al. Neglected Mycobacterium avium complex infection in a patient with prolonged pneumonia. Clin Lab. 2024;70(6). doi.10.7754/Clin.Lab.2024.240108 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Yano S. Mycobacterium avium infection improved by microbial substitution of fungal infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2010;2010:bcr0220102776. doi.10.1136/bcr.02.2010.2776 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Diel R, Lipman M, Hoefsloot W. High mortality in patients with Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):206. doi:10.1186/s12879-018-3113-x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cleveland Clinic. MAC lung disease. 2021. MAC Lung Disease: Causes, Symptoms and Treatment

- Daley CL, Winthrop KL. Mycobacterium avium complex: addressing gaps in diagnosis and management. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(Suppl 4):S199-211. doi.10.1093/infdis/jiaa354 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

The work had no special funding.

Author Information

Ashruta Patel

Department of Internal Medicine

Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, Georgia, USA

Email: ashrutapa@pcom.edu

Author Contribution

Ashruta Patel drafted and wrote the report.

Informed Consent

Ethics approval and informed consent to participate were obtained.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Ashruta P. Mycobacterium Avium Complex Infection Presentation with Rare Fungal Hyphae Diagnosed After Routine Preventive Screening. medtigo J Emerg Med. 2025;2(1):e3092212. doi:10.63096/medtigo3092212 Crossref