Author Affiliations

Abstract

Background: Headaches are a frequent complaint among individuals receiving dialysis for end-stage renal disease. This headache could be caused by the vast amount of water and electrolytes that shift. The study aims to figure out the prevalence of post-dialysis headaches (PDH) in Jordanian patients undergoing both peritoneal and hemodialysis, as well as to investigate the factors that may contribute to the development of PDH.

Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted between July 2024 and September 2024 at several tertiary hospitals within Jordan. Data collection involved primary techniques, including patient interviews with structured questionnaires that were filled out during the usual dialysis session. For the remaining medical history and follow-up, patient medical records were used.

Results: PDH was reported by 47.3% of patients, with a higher incidence in those who underwent hemodialysis compared to peritoneal dialysis. Significant factors associated with PDH included the patient’s age, duration of dialysis, dialysate glucose concentration, and the type of access line (p < 0.05). Furthermore, psychological stress, anxiety, prior migraines, dehydration, and volume overload were linked to increased PDH incidence. However, no significant associations were observed with gender or erythropoietin use.

Conclusion: PDH is a prevalent concern in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), especially in those who undergo frequent or prolonged hemodialysis sessions. Managing and optimizing hazards such as stress and dialysate glucose levels can help minimize the incidence of PDH, resulting in increased patient satisfaction.

Keywords

Post-dialysis headache (PDH), End-stage renal disease (ESRD), Hemodialysis, Migraine, Stress.

Introduction

One major issue in global public health is chronic renal disease[1,2], impacting 10–16% of adults globally.[3,8] Including ESRD, which is the last stage (5th stage) of chronic renal disease (CKD), with only 15% or less of the kidney functioning infiltration.[9] ESRD can be caused by a variety of factors, including diabetes, hypertension, autoimmune disorders, and certain medications. In the developed world, diabetes is thought to be the main cause of chronic renal disease, there is a significant risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and kidney failure in those with diabetes and chronic renal disease.[11,10]

The mainstay treatment for end-stage renal disease is regular hemodialysis.[12] There are two forms of dialysis: hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis, which both carry out normal kidney functions by filtering waste and excess fluid from the blood.[13] Hemodialysis catheters (HDC) are an essential part of kidney replacement therapy. While these catheters are regarded as a bridge to long-term vascular access, such as arteriovenous fistulas and grafts, they are associated with high morbidity and death, as well as increased healthcare costs. Despite these dangers, a considerable number of ESRD patients begin dialysis using these catheters.[14]

Globally, the number of patients receiving dialysis has been steadily rising, partly because of the increased prevalence of lifestyle problems that have increased the number of diabetes and hypertension cases. According to world health organization (WHO) estimates, 10% of the world’s population has CKD, leaving millions of patients dependent on dialysis or waiting for kidney transplants to survive.[15]

In Jordan, the burden of kidney disease is also rising, with CKD and ESRD being major health concerns. According to the Jordanian Ministry of Health, roughly 5,000 individuals were on dialysis in 2021, with the number expected to rise due to prevalent lifestyle problems that increased the number of diabetes and hypertension cases. The country’s dialysis services are mostly given in public hospitals, with hemodialysis being the most common type of therapy.[16,17]

Headache is one of the most common symptoms of hemodialysis.[18,19] The incidence of dialysis headaches ranges from 27% to 73%. This headache has a pulsatile pattern, a frontal position, moderate to severe severity, and begins a few hours after the start of dialysis.[19] The physiopathology of dialysis headaches remains unclear. However, there are factors known to relate to these headaches, including the type of dialysis solution used, variations in urea, sodium, and magnesium levels, as well as arterial blood pressure.[20] levels of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), and levels of substance P during dialysis.[21]

Methodology

The main aim of this cross-sectional study was to assess the impact of various variables on PDH in patients with ESRD obeying dialysis. The research was done in Jordan’s tertiary hospitals, and the data-collecting period lasted from July to September 2024. This study was conducted in strict accordance with the ethical standards established by the hospital’s research committee, adhering to the principles outlined in the 1964 declaration of helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The research protocol was rigorously reviewed and granted approval by the hospital’s research committee institutional review board (IRB/2024/4713). Additional approval for the research establishment and data collection was obtained from the head of the nephrology department, under whose supervision all data were collected.

The approval from the head department was contingent on the following conditions: Full compliance with the general policy of the hospital’s human research committee, strict confidentiality of all participant information, ensuring that data is used solely for scientific research purposes, mandatory informed consent from all participants prior to their involvement, prompt reporting of any modifications or unforeseen developments during the research to the head department. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were thoroughly briefed on the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Participants were reassured of their right to withdraw from the study at any point without repercussions, ensuring their autonomy and protection.

A total of 565 patients were included in the study, based on the availability of eligible patients in the dialysis centers during the data collection period. The sample size was chosen based on population size, guaranteeing sufficient strength to identify statistically significant correlations between patient characteristics and the incidence of headaches. The study involved both primary and secondary data collection methods. Primary data was collected through organized interviews, using questionnaires given directly to patients during their usual dialysis. For the secondary data collection, data were gathered through medical records for each patient. Furthermore, both data collection methods will be used to maximize the reliability and accuracy of these findings, as using only one method will not provide enough data for this type of research.

The questionnaire was designed to capture qualitative and quantitative data, including the probable causes and influence of multiple parameters on post-dialysis headaches. This structured approach ensured a comprehensive understanding of each patient’s condition.

During the interview the following questions were asked about the patient: age, gender, occupation, cause of ESRD, duration of ESRD, any symptoms of electrolytes disturbance, any Symptoms of dehydration, any symptoms of volume overload, any excessive caffeine intake or symptoms of caffeine withdrawal, if patient suffers from migraine, if patient have any health condition (such as diabetes mellites, hypertension, dyslipidemia, vascular condition (myocardial infarction (MI), cerebrovascular accident (CVA), stroke),secondary or tertiary hyperparathyroidism, anemia of chronic disease), whether the patient has ever used erythropoietin, any smoking habits, alcohol consumption, social support, type of dialysis (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis), times of dialysis per week, dialysis length, type of line used in dialysis, type of dialysis solution (dialysate), glucose concentration in the dialysate, if the patient suffers from stress and anxiety, intake of certain medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), some antibiotics like aminoglycosides, and immunosuppressants such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus) and whether the patient takes any vitamins or supplements.

After data collection, the data will be cleaned based on specific inclusion and exclusion criteria to define the study population and enhance validity. The inclusion criteria included adult patients 30 to 70 years old who have been diagnosed with ESRD and are undergoing either hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis, any patient who reports the occurrence of headaches within 24 to 48 hours following dialysis sessions and is diagnosed with ESRD, any patient with a history of headache or migraine, any patient with associated comorbidities, the patient must attend at least two to three dialysis sessions weekly and use medications such as NSAIDs, antibiotics, and immunosuppressants.

The exclusion criteria included patients with a history of neurological disorders like epilepsy or other conditions that could independently cause or exacerbate headaches, any patient who did not undergo regular dialysis or had an irregular treatment schedule, patients with acute or non-ESRD renal conditions requiring temporary dialysis, and patients who drank alcohol.

Following the end of the data collection, 565 responses in all were obtained. Then, the data was cleaned to make sure that each aspect of it satisfied the inclusion criteria and that none of them did not. The data was then imported into the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) software to begin the analysis.

Results

The study included 565 participants, all of whom met the inclusion criteria and none of whom were excluded. There was a balanced gender ratio of 285 females (50.4%) and 280 males (49.6%). Most participants were aged between 50-70 years, with 37.9% falling in the 50-60 age group and 37.5% in the 60-70 age group with variability in age, as indicated by a mean of 3 (50-60), a median of 3, and standard deviation of 1, suggests a relatively uniform distribution across the age categories used, with little deviation from the central age group. In terms of occupational status, a significant proportion were housewives (49.4%) and retirees (46.5%), while a smaller number were self-employed (3.4%), teachers (0.4%), or in the military (0.2%). The primary causes of ESRD were diabetes mellitus, affecting 166 participants (29.4%), recurrent infections such as urinary tract infections (UTIs) in 116 individuals (20.5%), hypertension in 107 cases (18.9%), and genetic conditions such as polycystic kidney disease, which affected 100 participants (17.7%). Other causes included autoimmune conditions (12.9%), renal agenesis (0.6%), and a combination of recurrent infections and renal agenesis (0.2%). As for the duration of ESRD, 52.9% had been living with the condition for 6-10 years, while 35% had it for 1-5 years, and only 9.2% had ESRD for more than 10 years. A small percentage (2.8%) had ESRD for less than one year. Post-dialysis headaches were also reported by 47.3% of participants (267 individuals), while 52.7% (298 individuals) did not experience headaches. Additionally, a large portion of the study population reported symptoms of electrolyte disturbances, such as muscle cramps, weakness, fatigue, and headaches, with 60.2% (340 participants) affected. Moreover, dehydration symptoms, including dry mouth, dizziness, and fatigue, were prevalent, reported by 56.6% (320 participants). Similarly, symptoms of volume overload, such as swelling in the extremities, bloating, and rapid weight gain, were reported by 60.2% (340 individuals). Furthermore, 53.1% (300 participants) indicated excessive caffeine intake or experienced caffeine withdrawal symptoms (Table 1).

| Table 1 | Count | Column N % | |

| What’s your gender | Female | 285 | 50.4% |

| Male | 280 | 49.6% | |

| Age | 30-40 | 29 | 5.1% |

| 40-50 | 110 | 19.5% | |

| 50-60 | 214 | 37.9% | |

| 60-70 | 212 | 37.5% | |

| Age (mean=3, median=3, standard deviation=1) | |||

| House – wife | 279 | 49.4% | |

| No work | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Retired | 263 | 46.5% | |

| Self-employment | 19 | 3.4% | |

| Teacher | 2 | 0.4% | |

| Works in the military | 1 | 0.2% | |

| The cause of ESRD? | Autoimmune | 73 | 12.9% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 166 | 29.4% | |

| Genetics like polycystic kidney | 100 | 17.7% | |

| Hypertension | 107 | 18.9% | |

| Recurrent infection like UTI | 116 | 20.5% | |

| Recurrent infection like UTI, Renal agenesis | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Renal agenesis | 2 | 0.4% | |

| The duration of ESRD? | 1-5 years | 198 | 35.0% |

| 6-10 years | 299 | 52.9% | |

| Less than one year | 16 | 2.8% | |

| More than 10 years | 52 | 9.2% | |

| Have you suffered from post dialysis headache | No | 298 | 52.7% |

| Yes | 267 | 47.3% | |

| Any Symptoms of electrolytes disturbance (muscle cramps, weakness, fatigue, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, headaches, irregular heartbeat, confusion, and in severe cases, seizures or even coma)? | No | 225 | 39.8% |

| Yes | 340 | 60.2% | |

| Any Symptoms of dehydration (feeling thirsty, having dry mouth, lips, and tongue, dizziness or lightheadedness, fatigue, infrequent urination with dark-colored urine, and headaches, in severe cases rapid breathing, fast heart rate, fever, and even confusion or irritability)? | No | 245 | 43.4% |

| Yes | 320 | 56.6% | |

| Any symptoms of volume overload (swelling in feet, ankles, and legs, abdomen and face, bloating, cramping, or headaches, Rapid weight gain)? | No | 225 | 39.8% |

| Yes | 340 | 60.2% | |

| Any excessive caffeine intake or symptoms of caffeine withdrawal? | No | 265 | 46.9% |

| Yes | 300 | 53.1% | |

The survey showed that 54.3% of the 565 participants experienced migraines, while 45.7% did not. As for underlying health conditions (co-morbidities associated), most participants had hypertension (33.3%), followed by a combination of dyslipidemia and anemia of chronic disease (17.0%). Other reported conditions included diabetes mellitus (4.1%) and various combinations of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and anemia of chronic disease. Only 0.5% of participants reported having no health condition. A significant majority (75.2%) had used erythropoietin, while 24.8% had not. In terms of smoking habits, 48.1% were current smokers, 15.6% were ex-smokers, and 36.3% had never smoked. Nearly all participants (99.3%) reported having someone to take care of them for social support. Most participants were undergoing hemodialysis (90.4%), while 9.6% were on peritoneal dialysis. Dialysis frequency varied, with 39.3% undergoing dialysis three times per week, 30.3% four times, 23.5% two times, and 6.9% five times per week (Table 2).

| Table 2 | Count | Column N % | |

| Do you suffer from migraine? | No | 258 | 45.7% |

| Yes | 307 | 54.3% | |

| Do you have any heath condition? | Anemia of chronic disease | 1 | 0.2% |

| Diabetes mellites | 23 | 4.1% | |

| Diabetes mellites, anemia of chronic disease | 51 | 9.0% | |

| Diabetes mellites, dyslipidemia | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Diabetes mellites, dyslipidemia, anemia of chronic disease | 2 | 0.4% | |

| Diabetes mellites, hypertension | 6 | 1.1% | |

| Diabetes mellites, hypertension, anemia of chronic disease | 9 | 1.6% | |

| Diabetes mellites, hypertension, dyslipidemia | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Diabetes mellites, hypertension, dyslipidemia, don’t suffer from anything | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Diabetes mellites, hypertension, vascular condition (MI, CVA, stroke), anemia of chronic disease | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Don’t suffer from anything | 3 | 0.5% | |

| Dyslipidemia | 61 | 10.8% | |

| Dyslipidemia, anemia of chronic disease | 96 | 17.0% | |

| Dyslipidemia, don’t suffer from anything | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Dyslipidemia, vascular condition (MI, CVA, stroke) | 4 | 0.7% | |

| Dyslipidemia, vascular condition (MI, CVA, stroke), anemia of chronic disease | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Hypertension | 59 | 10.4% | |

| Hypertension, anemia of chronic disease | 188 | 33.3% | |

| Hypertension, dyslipidemia | 14 | 2.5% | |

| Hypertension, dyslipidemia, anemia of chronic disease | 32 | 5.7% | |

| Hypertension, secondary or tertiary hyperparathyroidism | 2 | 0.4% | |

| Hypertension, vascular condition (MI, CVA, stroke) | 4 | 0.7% | |

| Hypertension, vascular condition (MI, CVA, stroke), anemia of chronic disease | 4 | 0.7% | |

| Have you ever used erythropetin? | No | 140 | 24.8% |

| Yes | 425 | 75.2% | |

| Do you smoke? | No | 205 | 36.3% |

| No, I am ex-smoker | 88 | 15.6% | |

| Yes | 272 | 48.1% | |

| Do you have someone who takes care of you? (Social support) | No | 4 | 0.7% |

| Yes | 561 | 99.3% | |

| Type of dialysis? | Hemodialysis | 511 | 90.4% |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 54 | 9.6% | |

| Times of dialysis per week? | Five times | 39 | 6.9% |

| Four times | 171 | 30.3% | |

| three times | 222 | 39.3% | |

| Two times | 133 | 23.5% | |

The majority (59.6%) of patients underwent dialysis for 3-5 hours. Various types of lines were used for dialysis, with 35.6% utilizing an arteriovenous (AV) fistula, 24.8% an AV graft, 30.1% a central venous catheter (CVC), and 9.6% a peritoneal dialysis catheter. Concerning dialysis solutions, 53.3% used Icodextrin, and 46.7% used a non-glucose solution. In terms of glucose concentration in dialysate, 46.7% used a solution without glucose, 24.4% used a concentration of 2.5, 14.9% used 4.25, and 14.0% used 1.5. Stress and anxiety were prevalent, with 68.1% of patients reporting these symptoms. Furthermore, 60.4% used medications such as NSAIDs, aminoglycosides, or immunosuppressants. Vitamin and supplement use was also common, with 53.5% reporting intake. (Table 3)

| Table 3 | Count | Column N % | |

| Dialysis length? | 0-2 hours | 2 | 0.4% |

| 3-5 hours | 337 | 59.6% | |

| 6-8 hours | 226 | 40.0% | |

| Type of Line used in dialysis: | AV fistula | 201 | 35.6% |

| AV graft | 140 | 24.8% | |

| CVC | 170 | 30.1% | |

| Peritoneal dialysis catheter (Tenckhoff Catheter) | 54 | 9.6% | |

| The type of Dialysis solution (dialysate)? | Icodextrin | 301 | 53.3% |

| Non-Glucose solution | 264 | 46.7% | |

| Glucose concentration in your dialysate? | 0 | 264 | 46.7% |

| 1.5 | 79 | 14.0% | |

| 2.5 | 138 | 24.4% | |

| 4.25 | 84 | 14.9% | |

| Do you suffer from stress and anxiety? | No | 180 | 31.9% |

| Yes | 385 | 68.1% | |

| Do you use one of these medications (NSAIDs), some antibiotics like aminoglycosides, and immunosuppressants such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus)? | No | 224 | 39.6% |

| Yes | 341 | 60.4% | |

| Do you take any vitamins or supplements? | No | 263 | 46.5% |

| Yes | 302 | 53.5% | |

Parameters influencing the incidence of post-dialysis headache:

The analysis of post-dialysis headaches among 565 patients reveals nuanced patterns across various demographic and clinical factors. Gender does not show a significant difference in the prevalence of post-dialysis headaches, with p-values of 0.909 for the Pearson Chi-Square and 0.976 for the Continuity Correction. Similarly, occupation does not exhibit a significant association with headache occurrence, as indicated by p-values of 0.133 and 0.068 for the Pearson Chi-Square and Likelihood Ratio tests, respectively. However, age shows a significant association with post-dialysis headaches, with older age groups, particularly those between 50-70 years, experiencing higher rates of headaches (p = 0.000). This association is reflected in the Phi and Cramer’s V values (0.246), which suggest a moderate effect size. The cause of ESRD is significantly linked to headache prevalence; those with autoimmune causes and diabetes mellitus are more likely to suffer from headaches (p = 0.000), with a notable Phi and Cramer’s V value of 0.290 indicating a strong association. The duration of ESRD also shows a borderline significant association with headaches, with a p-value of 0.054 for the Pearson Chi-Square test, suggesting a trend towards longer durations correlating with more headaches. Symptoms of electrolyte disturbances, such as muscle cramps and dizziness, do not show a significant association with headaches (p = 0.108).

However, dehydration symptoms (e.g., dry mouth, dizziness) are significantly associated with headaches (p = 0.045), as indicated by both the Chi-Square and Fisher’s Exact Test, while volume overload symptoms (e.g., swelling, rapid weight gain) also show a significant association with post-dialysis headaches (p = 0.034), reflecting a moderate effect size in Phi and Cramer’s V values. Excessive caffeine intake or symptoms of caffeine withdrawal do not show a significant correlation with post-dialysis headaches, with p-values of 0.222 for the Pearson Chi-Square and 0.238 for Fisher’s Exact Test. Similarly, erythropoietin use is not significantly linked to headaches (p = 0.537), suggesting that erythropoietin does not influence headache occurrence in this cohort. Migraine history is significantly associated with post-dialysis headaches (p = 0.007), indicating that individuals with a history of migraines are more prone to experiencing headaches after dialysis, with a Phi value of 0.113 reflecting a moderate association between migraine history and headache prevalence.

Health conditions present a strong correlation with post-dialysis headaches (p = 0.000), with various conditions such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and their combinations showing a significant impact on headache occurrence. The analysis reveals a strong effect size (Phi = 0.398), indicating that the presence of multiple health conditions substantially increases the likelihood of experiencing headaches. Smoking status is significantly associated with post-dialysis headaches (p = 0.000), with smokers more likely to suffer from headaches compared to non-smokers and ex-smokers, reflecting a substantial effect size (Phi = 0.356). Social support plays a significant role in headache prevalence (p = 0.034), with patients with social support less likely to experience post-dialysis headaches compared to those without social support; the negative Phi value of -0.089 suggests that social support has a mitigating effect on the occurrence of headaches.

Furthermore, hemodialysis is strongly associated with post-dialysis headaches compared to peritoneal dialysis, with a chi-square value of 49.385 and a p-value of 0.000, reflecting a significant association with a Phi coefficient of -0.296, indicating that hemodialysis is linked to a higher incidence of headaches. Among those on hemodialysis, the frequency of dialysis sessions per week impacts headache occurrence, with the highest headache rates observed in patients undergoing four sessions (97 headaches) and three sessions (112 headaches) compared to fewer sessions, with a chi-square value of 44.281 and a p-value of 0.000, indicating a moderate association (Phi = 0.280). The duration of each dialysis session is another contributing factor, with sessions lasting 3-5 hours associated with 141 headaches and those lasting 6-8 hours with 126 headaches, reflecting a significant association (p = 0.002, Phi = 0.148). Additionally, the type of dialysis access line impacts headache frequency, with CVCs and AV fistulas associated with higher headache rates, with a chi-square value of 51.963 and a p-value of 0.000, and a Phi coefficient of 0.303, indicating a strong association. The type of dialysis solution used is also a factor, with non-glucose solutions correlating with a higher incidence of headaches compared to Icodextrin solutions, shown by a chi-square value of 14.113 and a p-value of 0.000, with a Phi coefficient of 0.158.

Similarly, glucose concentration in dialysate affects headache frequency, with higher concentrations (2.50 and 4.25%) associated with increased headache rates, as indicated by a chi-square value of 25.232 and a p-value of 0.000, with a Phi coefficient of 0.211. Stress and anxiety are significant contributors to headache incidence, with those reporting stress and anxiety experiencing more headaches, supported by a chi-square value of 9.522 and a p-value of 0.002, reflecting a moderate association (Phi = 0.130). The use of medications such as NSAIDs, antibiotics, and immunosuppressants is associated with a higher likelihood of headaches, with a chi-square value of 6.807, a p-value of 0.009, and a Phi coefficient of -0.110, indicating a weaker but notable association. Conversely, vitamin or supplement use does not show a significant impact on headache occurrence (p = 0.962, Phi = 0.002).

Discussion

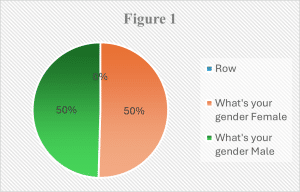

The main aim of this study was to thoroughly examine the parameters linked to PDH. The findings reveal a balanced gender distribution among participants, with a slight female predominance (Figure 1).

This disparity can be attributed to differences in health-seeking behavior between genders, as women are generally more likely to seek medical attention for perceived health issues.[22] Additionally, women may have a higher risk of developing CKD due to factors such as urinary tract infections, pregnancy-related complications, and autoimmune diseases.[23,25]

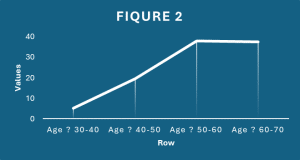

The study also indicates that most CKD patients undergoing dialysis are between 50 and 60 years old. (Figure 2) This age group is more susceptible to CKD due to the aging process, which, coupled with various risk factors and the hemodynamic and non-hemodynamic effects of renin-angiotensin system activation, increases the likelihood of developing kidney disease.[24] Moreover, patients in this age group often have a higher burden of comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, kidney stones, a family history of kidney failure, and prolonged use of over-the-counter pain medications.

These factors contribute to the increased prevalence of CKD in older adults, leading to the National Kidney Foundation’s recommendation for annual kidney disease screening for individuals over 60.[26] Older adults may also be more prone to fluid and electrolyte imbalances, which can be exacerbated by the rapid shifts and stress associated with dialysis.[27]

Diabetes mellitus is a leading cause of CKD, contributing to kidney damage through several complex mechanisms. (Figure 3) One major pathway is diabetic nephropathy, which results from the hemodynamic effects of hyperglycemia.

High blood sugar increases renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate (GFR), leading to a state of hyperfiltration that places excessive stress on the glomeruli. Over time, this results in glomerular hypertrophy, the enlargement of kidney filtration structures, and glomerulosclerosis, a condition where the glomeruli become scarred and lose their ability to filter blood effectively.[28] In addition to these hemodynamic changes, glycoprotein modifications occur in the glomerular basement membrane due to elevated blood sugar, thickening the membrane and increasing its permeability, which allows proteins to leak into the urine. Diabetes mellitus also promotes chronic inflammation and fibrosis within the kidneys, further accelerating kidney damage and loss of function.[28] Another key manifestation of diabetes mellitus-induced kidney disease is nodular glomerulosclerosis, which is closely associated with Kimmelstiel-Wilson syndrome. This condition is characterized by the formation of distinct nodular lesions within the glomeruli. These nodules form due to the same hyperfiltration and glomerular damage that underlie diabetic nephropathy, leading to further decline in kidney function.[28] Furthermore, diabetes mellitus can lead to interstitial nephritis, a condition marked by inflammation and damage to the kidney tubules. The chronic inflammation that accompanies diabetes mellitus often results in tubulointerstitial fibrosis, a process where scar tissue replaces healthy kidney tissue. This scarring is a major driver of disease progression, and the degree of tubulointerstitial damage strongly correlates with the severity of diabetic nephropathy.[29]

DM also increases the risk of ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO), a condition where the flow of urine from the kidneys to the bladder is blocked, potentially causing kidney damage. This increased risk adds another dimension to the impact of diabetes mellitus on renal health.[30] UTIs are a significant factor in kidney damage, especially in patients with CKD, whose compromised immune systems make them more vulnerable. The metabolic and inflammatory changes that accompany CKD, along with the frequent medical interventions required by these patients, further elevate the risk of UTIs. If left untreated, UTIs can ascend to the kidneys, leading to infections such as pyelonephritis, which can cause severe kidney damage.[31]

Hypertension is both a cause and a consequence of CKD, affecting most patients with the condition. Elevated blood pressure places significant strain on the kidneys, damaging the delicate structures within and leading to further impairment of kidney function. Managing hypertension in patients with CKD is essential. It helps to slow down the progression of kidney disease and reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), which is common in this population. As CKD advances and the estimated GFR decreases, hypertension tends to worsen and becomes harder to control.[32,33]

Genetic conditions, such as autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), add yet another layer of complexity to CKD. ADPKD is the most common inherited cause of ESKD worldwide. This condition leads to the formation of numerous cysts in the kidneys, which progressively enlarge and disrupt normal kidney function. Without intervention, ADPKD can result in ESKD, requiring life-sustaining treatments such as hemodialysis, renal transplantation, or peritoneal dialysis to maintain renal function.[34] Thus, the interplay between DM, hypertension, UTIs, and genetic disorders like ADPKD highlights the multifactorial nature of kidney damage, illustrating how various conditions can contribute to the progressive decline of kidney function, ultimately leading to ESKD.

The prevalence of post-dialysis headaches in patients with ESRD appears to be significantly influenced by the underlying cause of ESRD, particularly in individuals with autoimmune conditions and DM. Patients with ESRD due to autoimmune diseases are more prone to develop post-dialysis headaches, as headaches are a common symptom of central nervous system (CNS) involvement in autoimmune disorders.[35] There is substantial evidence supporting the involvement of the immune system in the pathogenesis of headaches, especially migraines. Alterations in cytokine profiles and lymphocyte subsets have been observed in patients suffering from headaches, indicating potential immune system dysregulation. Additionally, many genetic and environmental factors that play a role in the onset of headaches, especially migraines, are similar to those observed in immunological and autoimmune diseases. Consequently, these immunological changes might make individuals more susceptible to both primary headaches and autoimmune conditions. Conversely, in some cases, the mechanisms that cause autoimmune diseases may also trigger the onset of headaches.[36] The connection between diabetes (DM) and headaches is significant due to the impact of diabetes on vascular reactivity, which is a key factor in migraine development. Diabetes can impair vascular function, cause diabetic neuropathy, and lead to lifestyle changes that may worsen migraines.[37,38]

Diabetic neuropathy, a common complication of diabetes mellitus, can also influence headache prevalence by affecting the nerves and blood vessels in the head and neck.[39] Furthermore, recent genetic studies have sparked interest in the potential genetic link between diabetes mellitus and migraines, suggesting that shared genetic factors might underlie both conditions.[40,41] This relationship between autoimmune diseases, diabetes mellitus, and headache pathophysiology highlights the complex interplay between the immune system, vascular health, and neurological function in patients with ESRD, making post-dialysis headaches more prevalent in these populations.

Dehydration, even when mild, has been shown in some studies to contribute to permanent kidney damage, which is another factor affecting post-dialysis headaches.[42] People are continuously losing water through various means, including the skin, lungs, kidneys, and gastrointestinal (GI) tract. When water loss exceeds intake, receptors in the brain detect the deficiency and prompt the release of antidiuretic hormone. This hormone signals the kidneys to reabsorb more water to conserve fluid. As dehydration progresses and blood pressure decreases, the kidneys release an enzyme called renin, which plays a critical role in the body’s fluid balance. Renin converts the hormone angiotensin 1 to angiotensin 2, which in turn stimulates the adrenal glands to release aldosterone, another hormone that increases the kidneys’ reabsorption of both water and sodium. This cascade of hormonal responses is aimed at maintaining blood volume and pressure, but prolonged dehydration can strain the kidneys and exacerbate their damage. Additionally, dehydration has been linked to the development of UTIs and kidney stones, both of which can further impair kidney function and contribute to discomfort or complications post-dialysis.[36]

Individuals with a history of migraines are more susceptible to experiencing PDH due to the interplay of multiple factors associated with both dialysis and migraine pathophysiology. Migraine headaches are often triggered by changes in cerebral vessel diameter, involving the trigeminal nerve, and this vascular reactivity is highly sensitive to fluctuations in blood pressure.[42] In PDH, the blood pressure changes that occur during dialysis may mimic these vascular triggers, leading to the onset of migraine-like headaches. Additionally, individuals with migraines have a more excitable central nervous system, which makes them more prone to develop headaches, including PDH.[43]

There are several reasons why people with migraines are more likely to experience headaches after dialysis. Firstly, the fluid shifts during dialysis, where large amounts of fluid are rapidly removed and replaced, can trigger migraine attacks in vulnerable individuals. Dehydration, which is common in dialysis, can worsen headaches. This is like high-altitude headaches, where dehydration plays a significant role in triggering secondary headache disorders.[44] Secondly, electrolyte imbalances during dialysis, particularly fluctuations in sodium, potassium, and magnesium levels, can act as migraine triggers. These electrolyte disturbances are thought to play a key role in the pathogenesis of migraines by affecting neural and vascular function.[45]

Blood pressure fluctuations during dialysis also contribute to headache development, as changes in vascular tone can easily provoke migraine attacks in sensitive individuals.[46] Furthermore, the stress and anxiety associated with the dialysis process may aggravate headache symptoms, as both are known triggers for migraines. Anxiety disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), often manifest as headaches, indicating a strong connection between psychological stress and the frequency of headaches.[47] This suggests that patients with social support are less likely to experience post-dialysis headaches compared to those without social support, due to the reduced incidence of anxiety and depression.[48] Therefore, individuals with a history of migraines are particularly vulnerable to experiencing PDH due to the combined effects of fluid shifts, electrolyte disturbances, blood pressure changes, and the stress inherent in the dialysis process.

Research has shown that smoking significantly worsens PDH, with a higher occurrence of PDH in smokers.[48] Smoking contributes to PDH primarily through vasoconstriction, which is the narrowing of blood vessels. Nicotine, a major component of tobacco, triggers this vasoconstriction, reducing blood flow to different parts of the body, including the brain and its protective layers called the meninges. The decrease in blood flow can lower brain activity, which is a significant factor in the development of migraines. Reduced circulation to the meninges can lead to intense pain, often felt in the back of the head or the face.[49] Moreover, nicotine can activate pain-sensitive nerves that travel through the back of the throat, raising the chances of headaches in smokers. Neural stimulation can exacerbate the heightened sensitivity to pain during migraines, causing more frequent and intense headaches in people exposed to nicotine. For many individuals, eliminating the trigger of nicotine can alleviate headaches, demonstrating a direct connection between smoking and headache development. The combination of vasoconstriction, reduced cerebral blood flow, and neural irritation highlights the crucial role of smoking in worsening PDH, particularly in individuals already prone to migraines or other headache disorders. Therefore, quitting smoking may be a key factor in reducing the frequency and severity of PDH in affected patients.[50] Furthermore, the study found that patients with existing medical conditions such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus, as well as combinations of these conditions, were at a higher risk of developing PDH. These factors are known to have a detrimental impact on vessel health and the regulation of cerebral blood flow.[50]

In patients with DM, there are changes in vascular reactivity and nerve conduction that may be relevant to migraine pathophysiology.[51] When a headache patient comes to the emergency room, doctors should first use the IHS criteria to classify his or her headache. Following this, if indicated, the blood pressure levels should be measured.[52] Regarding dyslipidemia, previous research has indicated that there is an association between migraine and higher levels of cholesterol and LDL compared to the control group, with a significant relationship being found.[53] Headaches are a common neurological symptom during hemodialysis, but they have been less studied in peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients. PD patients have significantly lower diastolic blood pressure than hemodialysis patients, while hemodialysis patients have significantly lower hemoglobin levels compared to PD patients. When it comes to dialysis methods, patients on hemodialysis are more likely to develop PDH than those on peritoneal dialysis. Peritoneal dialysis provides more stable blood pressure, electrolyte values, and fluid status compared to hemodialysis.[54,55] The cause of dialysis headaches is not fully understood. Factors associated with these headaches include the type of dialysis solution used (acetate poses a greater risk of dialysis headache than bicarbonate); fluctuations in urea, sodium, and magnesium levels, as well as arterial blood pressure; levels of CGRP and substance P during dialysis. The blood-brain barrier may play a significant role in developing this headache. The concentration gradient between the brain and the blood during dialysis, leading to the passage of free water through the blood-brain barrier, may result in cerebral edema in some patients, consequently causing headaches.[56,57] Additionally, the type of dialysis solution used was a factor in developing PDH. Non-glucose solutions used in hemodialysis were found to provoke PDH more often compared to Icodextrin solutions, which are used in peritoneal dialysis.[58]

The use of medications like NSAIDs, antibiotics, and immunosuppressants is linked to a higher probability of experiencing headaches after dialysis. Dialysis patients are prone to overusing NSAIDs, which can lead to medication-overuse headaches. According to the Drug Class and Duration of Headache, medication overuse headaches from NSAIDs occur when the medication is used for more than 15 days per month for over 3 months.[59] Antibiotics may be linked to changes in the gut microbiota, which are influenced by antibiotic use and other factors. Dysbiosis, a condition that develops and persists because of earlier antibiotic therapy, changes the composition of the intestinal flora. This can lead to the development of various diseases such as metabolic disorders, obesity, hematological malignancies, neurological or behavioral disorders, and migraine. Metabolites produced by the gut microbiome have been shown to influence the gut-brain axis.[60] Immunosuppressive agents, such as cyclosporine, tacrolimus (Prograf), and muromonab CD3 (OKT3), are commonly associated with headaches.[61] They can also worsen existing headache syndromes and lead to the development of encephalopathies, with headache as a clinical feature.[62]

The prevalence of PDH among patients undergoing hemodialysis has been a topic of significant research interest in various regions. Sattar (2016) conducted a study in Karachi, Pakistan, which included a sample of 150 participants. The findings indicated that 14% of patients experienced headaches following dialysis, with a higher incidence noted among diabetic individuals. This highlights the potential influence of comorbid conditions on the occurrence of PDH.[56]

In contrast, Sousa Melo (2022) conducted a cross-sectional study involving 100 participants and found a considerably higher prevalence, with nearly 50% reporting dialysis headaches. The study established a significant association between the frequency of dialysis sessions and the occurrence of headaches, suggesting that more frequent treatments may increase the likelihood of experiencing PDH.[63]

Similarly, Chhaya (2022) examined headaches in patients with end-stage renal disease in India, focusing on 128 participants. The study reported that 48 patients experienced PDH, predominantly among women. Interestingly, it found no significant differences in electrolyte levels between patients with and without PDH, indicating that other factors may be at play in the pathophysiology of these headaches.[64]

Yang Y (2023) further contributed to this body of literature by evaluating the applicability of diagnostic criteria for hemodialysis-related headaches based on the international classification of headache disorders. In this study, which involved 154 patients, only 6.49% (10 patients) reported PDH, with a notably higher prevalence in females. This discrepancy in prevalence rates across studies emphasizes the variability in PDH among different populations.[65]

Collectively, these studies indicate a significant prevalence of post-dialysis headaches, although rates vary widely by region and population. While some studies suggest a higher incidence among females, other research, including our findings, reports no gender differences. Furthermore, the correlation between the frequency of dialysis sessions and headache occurrence appears to be a consistent theme across multiple studies, reinforcing the need for further investigation into the underlying mechanisms and potential interventions to mitigate this issue.

Limitations and expectations:

Despite the valuable insights demonstrated by the research, certain constraints must be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design may limit the ability to establish causation between the investigated aspects and the occurrence of post-dialysis headaches. Owing to the nature of this study, it was unable to assess how changes over time affect the incidence of headaches. Furthermore, the study was limited to certain Jordanian hospitals, which may have resulted in selection bias, especially considering the disparity in socioeconomic variables across patients in different Jordanian hospitals. Another drawback is using self-reported data to report symptoms and other influencing factors. This makes the study prone to recall bias and variation in individual pain thresholds and reporting tendencies.

This study definitively analyzes the multiple factors that influence the occurrence of post-dialysis headaches among ESRD patients in Jordan and establishes correlations that can be directly applied in clinical practice. The findings are expected to reveal demographic, physiological, and possibly psychological characteristics strongly associated with post-dialysis headaches. Additionally, the research aims to pinpoint potential areas for further studies to enhance patient care and management. This could ultimately result in the development of customized strategies and guidelines to reduce headaches in this patient population, thus improving their overall well-being.

Finally, Chronic renal disease presents a critical challenge to public health, with increasing incidence rates globally, particularly in developing countries like Jordan. While hemodialysis remains a vital treatment modality for ESRD, associated complications such as dialysis-related headaches warrant further investigation to improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

Conclusion

PDH is a serious concern among ESRD patients, with diabetes mellitus being the most common cause. There was a robust relationship between PDH and the older age group, with no gender disparities. Autoimmunity diseases and diabetes, the most prevalent causes of ESRD, have a strong association with PDH. Dehydration and volume overload symptoms are very strongly associated with PDH. People who have a history of migraines are also more likely to develop PDH. Common co-morbidities include hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and their combinations. Smoking and a lack of social support are strongly associated with PDH. Patients on hemodialysis were more likely to develop PDH than those on peritoneal dialysis. PDH prevalence arose with more and longer sessions, with moderate to substantial relationships. Central venous catheter and AV fistula dialysis contributed to a higher prevalence of PDH and a stronger correlation than other lines. The glucose concentration in the dialysate plays a crucial role, with greater concentrations resulting in more frequent PDH. Stress and anxiety were significant factors contributing to headaches after dialysis. A history of drug use, including NSAIDs, antibiotics, and immunosuppressants, was associated with an increased risk of developing PDH.

References

- Barsoum RS. Chronic kidney disease in the developing world. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(10):997-999. doi:10.1056/NEJMp058318 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Meguid El Nahas A, Bello AK. Chronic kidney disease: The global challenge. 2005;365(9456):331-340. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17789-7 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, et al. The definition, classification, and prognosis of chronic kidney disease: A KDIGO controversies conference report. Kidney Int. 2011;80(1):17-28. doi:10.1038/ki.2010.483

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Hallan SI, Coresh J, Astor BC, et al. International comparison of the relationship of chronic kidney disease prevalence and ESRD risk. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(8):2275-2284. doi:10.1681/ASN.2005121273

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Chadban SJ, Briganti EM, Kerr PG, et al. Prevalence of kidney damage in Australian adults: The AusDiab kidney study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(2). doi:10.1097/01.ASN.0000070152.11927.4A PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wen CP, Cheng TY, Tsai MK, et al. All-cause mortality attributable to chronic kidney disease: A prospective cohort study based on 462,293 adults in Taiwan. 2008;371(9624):2173-2182. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60952-6 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. 2007;298(17):2038-2047. doi:10.1001/jama.298.17.2038 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(2 Suppl 1). K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification

- Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, et al. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(2):137-147.

doi:10.7326/0003-4819-139-2-200307150-00013 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Fox CS, Larson MG, Leip EP, Culleton B, Wilson PW, Levy D. Predictors of new-onset kidney disease in a community-based population. 2004;291(7):844-850. doi:10.1001/jama.291.7.844 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Collins AJ, Foley RN, Chavers B, et al. ‘United States Renal Data System 2011 Annual Data Report: Atlas of chronic kidney disease & end-stage renal disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(1 Suppl 1):A7-e420. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.015 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Basile C, Davenport A, Mitra S, et al. Frontiers in hemodialysis: Innovations and technological advances. Artif Organs. 2021;45(2):175-182. doi:10.1111/aor.13798 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- National Kidney Foundation. Dialysis. National Kidney Foundation. Accessed September 2, 2021. Dialysis

- El Khudari H, Ozen M, Kowalczyk B, Bassuner J, Almehmi A. Hemodialysis catheters: Update on types, outcomes, designs, and complications. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2022;39(1):90-102. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1742346 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- World Health Organization. Chronic kidney disease. World Health Organization. Chronic kidney disease

- Ministry of Health, Jordan. Annual health report. Ministry of Health, Jordan. Annual health report

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Global burden of disease Jordan profile. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Retrieved from Global burden of disease Jordan profile

- Bana DS, Yap AU, Graham JR. Headache during hemodialysis. 1972;12(1):1-14. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1972.hed1201001.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sousa Melo E, Carrilho Aguiar F, Sampaio Rocha-Filho PA. Dialysis headache: A narrative review. 2017;57(1):161-164. doi:10.1111/head.12875 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gozubatik-Celik G, Uluduz D, Goksan B, Akkaya N, Sohtaoglu M, Uygunoglu U. Hemodialysis-related headache and how to prevent it. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26(1):100-105. doi:10.1111/ene.13777 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Alessandri M, Massanti L, Geppetti P, Bellucci G, Cipriani M, Fanciullacci M. Plasma changes of calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P in patients with dialysis headache. 2006;26(11):1287-1293. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01217.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lewandowski MJ, Krenn S, Kurnikowski A, et al. Chronic kidney disease is more prevalent among women but more men than women are under nephrological care: Analysis from six outpatient clinics in Austria 2019. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2023;135(3-4):89-96. doi:10.1007/s00508-022-02074-3 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- National Kidney Foundation. Kidney Failure Risk Factor: Gender (Sex). National Kidney Foundation. Accessed September 2, 2021. Kidney Failure Risk Factor: Gender (Sex)

- Mallappallil M, Friedman EA, Delano BG, McFarlane SI, Salifu MO. Chronic kidney disease in the elderly: evaluation and management. Clin Pract (Lond). 2014;11(5):525-535. doi:10.2217/cpr.14.46 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Billi AC, Kahlenberg JM, Gudjonsson JE. Sex bias in autoimmunity. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2019;31(1):53-61. doi:10.1097/BOR.0000000000000564 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- National Kidney Foundation. Aging and Kidney Disease. National Kidney Foundation. Accessed September 2, 2021. Aging and Kidney Disease

- Schlanger LE, Bailey JL, Sands JM. Electrolytes in the aging. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17(4):308-319. doi:10.1053/j.ackd.2010.03.008 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Nordheim E, Jenssen TG. Chronic kidney disease in patients with diabetes mellitus. Endocr Connect. 2021;10(5). doi:10.1530/EC-21-0097 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Tonolo G, Cherchi S. Tubulointerstitial disease in diabetic nephropathy. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2014;7:107-115. doi:10.2147/IJNRD.S37883 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sun L, Zhao D, Zhu L, Shen Y, Zhao Y, Tang D. Asymptomatic obstructive hydronephrosis associated with diabetes insipidus: a case report and review. Transl Pediatr. 2021;10(6):1721-1727. doi:10.21037/tp-20-476 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Scherberich JE, Fünfstück R, Naber KG. Urinary tract infections in patients with renal insufficiency and dialysis – epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical symptoms, diagnosis and treatment. GMS Infect Dis. 2021;9:Doc07. doi:10.3205/id000076 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Pugh D, Gallacher PJ, Dhaun N. Management of hypertension in chronic kidney disease. 2019;79(4):365-379. Erratum in: Drugs. 2020;80(13):1381. doi:10.1007/s40265-019-1064-1 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Muntner P, Anderson A, Charleston J, et al. Hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in adults with CKD: results from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(3):441-451. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.09.014 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mahboob M, Rout P, Leslie SW, Bokhari SRA. Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. March 20, 2024. Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease

- John S, Hajj-Ali RA. Headache in autoimmune diseases. 2014;54(3):572-582. doi:10.1111/head.12306 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Biscetti L, De Vanna G, Cresta E, et al. Headache and immunological/autoimmune disorders: a comprehensive review of available epidemiological evidence with insights on potential underlying mechanisms. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18(1):1-18. doi:10.1186/s12974-021-02229-5 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Tantucci C, Bottini P, Fiorani C, et al. Cerebrovascular reactivity and hypercapnic respiratory drive in diabetic autonomic neuropathy. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:889-896. doi:10.1152/jappl.2001.90.3.889

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Wijnhoud AD, Koudstaal PJ, Dippel DW. Relationships of transcranial blood flow Doppler parameters with major vascular risk factors: TCD study in patients with a recent TIA or nondisabling ischemic stroke. J Clin Ultrasound. 2006;34:70-76. doi:10.1002/jcu.20193 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ziegler D. Treatment of diabetic polyneuropathy: update 2006. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1084:250-266. doi:10.1196/annals.1372.008 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- McCarthy LC, Hosford DA, Riley JH, et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphism alleles in the insulin receptor gene are associated with typical migraine. 2001;78:135-149. doi:10.1006/geno.2001.6647 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Curtain R, Tajouri L, Lea R, MacMillan J, Griffiths L. No mutations detected in the INSR gene in a chromosome 19p13 linked migraine pedigree. Eur J Med Genet. 2006;49(1):57-62. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2005.01.015 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Pescador Ruschel MA, De Jesus O. Migraine headache. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Migraine Headache

- Haigh S, Karanovic O, Wilkinson F, Wilkins A. Cortical hyperexcitability in migraine and aversion to patterns. 2012;32(3):236-240. doi:10.1177/0333102411433301 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Arca KN, Halker Singh RB. Dehydration and headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2021;25(8):56. doi:10.1007/s11916-021-00966-z PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cegielska J, Szmidt-Sałkowska E, Domitrz W, et al. Migraine and its association with hyperactivity of cell membranes in the course of latent magnesium deficiency: preliminary study of the importance of the latent tetany presence in the migraine pathogenesis. Nutrients. 2021;13(8):2701. doi:10.3390/nu13082701 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Seçil Y, Unde C, Beckmann YY, et al. Blood pressure changes in migraine patients before, during and after migraine attacks. Pain Pract. 2010;10(3):222-227. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2009.00349.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Moore W. Anxiety headache. August 25, 2022. Anxiety Headache

- Weinberger AH, Seng EK. The relationship of tobacco use and migraine: a narrative review. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2023;27(4):39-47. doi:10.1007/s11916-023-01103-8 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi. Smoking and Headache. 2021. Smoking and Headache

- Wang S, Tang C, Liu Y, et al. Impact of impaired cerebral blood flow autoregulation on cognitive impairment. Front Aging. 2022;3:1077302. doi:10.3389/fragi.2022.1077302 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Aamodt AH, Stovner LJ, Midthjell K, et al. Headache prevalence related to diabetes mellitus: the Head-HUNT study. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14(7):738-744. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01765.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Benseñor IM. Hypertension and headache: a coincidence without any real association. Sao Paulo Med J. 2003;121(5):183-184. doi:10.1590/S1516-31802003000500001 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Assarzadegan F, Hosseinpanahi SP, Hesami O, Mansouri B, Lima BS. Frequency of dyslipidemia in migraineurs in comparison to control group. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2019;8(3):950. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_9_19 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Demır ÜF, Bozkurt O. Effects of perceived social support, depression and anxiety levels on migraine. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2020;57(3):210-215. doi:10.29399/npa.25000 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Zhao Y. Comparison of the effect of hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis in the treatment of end-stage renal disease. Pak J Med Sci. 2023;39(6):1562-1567. doi:10.12669/pjms.39.6.8056 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sousa Melo E, Pedrosa RP, Carrilho Aguiar F, Valente LM, Sampaio Rocha-Filho PA. Dialysis headache: characteristics, impact and cerebrovascular evaluation. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2022;80(2):129-136. doi:10.1590/0004-282x-anp-2021-0133 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Frampton JE, Plosker GL. Icodextrin: a review of its use in peritoneal dialysis. 2003;63(19):2079-2105. doi:10.2165/00003495-200363190-00011 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Fischer MA, Jan A. Medication-overuse headache. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Medication-Overuse Headache

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9):629-808. doi:10.1177/0333102413485658 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kappéter Á, Sipos D, Varga A, et al. Migraine as a disease associated with dysbiosis and possible therapy with fecal microbiota transplantation. Microorganisms. 2023;11(8):2083. doi:10.3390/microorganisms11082083 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rozen TD. Migraine headache: immunosuppressant therapy. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2002;4(5):395-401. doi:10.1007/s11940-002-0050-0 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Toth CC, Burak K, Becker W. Recurrence of migraine with aura due to tacrolimus therapy in a liver transplant recipient successfully treated with sirolimus substitution. Headache. 2005;45(3):245-246. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05053_1.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sattar S. Post-dialysis effects in patients undergoing hemodialysis: a study in Karachi, Pakistan. J Renal Health. 2016;3(2):120-125. Post-dialysis effects in patients on haemodialysis

- Chhaya KT. Headaches associated with hemodialysis in patients with end-stage renal disease in India. Int J Nephrol. 2022;15(3):207-214. Headache Associated with Hemodialysis in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease in India: A Common Yet Overlooked Comorbidity

- Yang Y, Meng F, Zhu H, et al. The applicability research of the diagnostic criteria for 10.2 Heamodialysis-related headache in the international classification of headache disorders-3rdJ Headache Pain. 2023;24(1):19. doi:10.1186/s10194-023-01548-7 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

Not reported

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Saed Bani Amer

Department of Medicine

Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

Email: saedbamer0000@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Yara Al-Slati

Department of Medicine

Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

Lina Badawneh, Ali Bani Hanib, Khaled Al-Wakfi, Rama Zghoul, Retaj Al-As-hab

Department of Medicine

Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

Raed Bani Amer

Department of Medicine

Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan

Hashem Al-Shorman and Hasan Al-Khateeb

Department of Internal Medicine specialist and consultant

Princess Basma Hospital, Jordan

Qaed Bani Amer

Department of Internal Medicine

Princess Basma Hospital, Jordan

Saif kailani

Department of Medicine

King Abdullah University Hospital, Jordan

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in strict accordance with the ethical standards established by the hospital’s research committee, adhering to the principles outlined in the 1964 declaration of helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The research protocol was rigorously reviewed and granted approval by the hospital’s research committee (IRB approval number: IRB/2024/4713). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were thoroughly briefed on the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Not reported

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Saed Bani Amer, Yara A-S, Lina B, et al. Multifactorial Determinants of Post-Dialysis Headaches: Insights from a Jordanian Cross-Sectional Study. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622412. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622412 Crossref