Author Affiliations

Abstract

Aim: This is the first study in Jordan that investigates the main demographic and health characteristics that determine the form of gallbladder disease, as well as the intraoperative and postoperative complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. It also investigates post-cholecystectomy syndrome and risk variables among laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients.

Method: Data was collected using a validated questionnaire, patient interviews, and a thorough evaluation of available research and literature. Both primary and secondary data were carefully examined to ensure accurate results, with data cleaning based on precise inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Results: A total of 722 replies were collected from post-cholecystectomy patients. Gallstone spilling and biliary tract injuries were the most prevalent intraoperative complications, reported by 56.8% of patients. Age (p < 0.001), obesity (p < 0.001), smoking (p = 0.008), and alcohol intake (p = 0.045) all had a significant correlation with complications. Overall, postoperative care was satisfactory, with 97.2% of patients undergoing early mobilization and 97.5% receiving sufficient pain relief. 82.3% of patients reported symptoms of post-cholecystectomy syndrome, which included nausea, vomiting, heartburn, flatulence, diarrhea, and intermittent stomach discomfort, whereas 17.7% did not.

Conclusion: Certain factors have been recognized as generating intraoperative and postoperative complications. Obesity, smoking, alcoholism, and comorbidities are some instances. The type of gallbladder disease, particularly acute cholecystitis and cholesterol stones, is significant in predicting serious consequences. Gender, age, prior surgeries, and psychological factors have all been related to an increased risk of postoperative complications such as nausea, vomiting, and post-cholecystectomy syndrome.

Keywords

Intraoperative complications, Postoperative complications, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Post-cholecystectomy syndrome.

Introduction

One of the most prevalent surgical conditions treated by general surgeons is gallbladder disorders.[1] In clinical practice, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is now regarded as the gold standard for cholelithiasis patients.[2], It is a minimally invasive surgical technique that involves removing a diseased gallbladder.[3] Since the early 1990s, this technique has effectively replaced the open technique for routine cholecystectomies.[3]

Gallbladder disorders encompass a wide range of conditions such as cholecystitis, which can present in either acute or chronic form. Acute cholecystitis is an acute inflammatory response that typically begins when a persistent obstruction by a gallstone causes increased pressure within the gallbladder, leading to enlargement, ischemia, bacterial invasion, and subsequent inflammation.[4] Chronic cholecystitis occurs after repeated episodes of mild attacks of cholecystitis or by chronic irritation of massive gallstone production and is characterized by mucosal atrophy and fibrosis of the gallbladder wall.[4] As acute cholecystitis progresses, it can lead to empyema, often following bile stasis and cystic duct obstruction. Empyema is considered a surgical emergency that may cause septic shock if not treated immediately.[5] On the other hand, the presence of one or more gallstones in the common bile duct (CBD) is known as choledocholithiasis, which is the primary cause of benign biliary blockages.[6] If the obstruction of the CBD progresses to an infection, it causes a life-threatening condition known as cholangitis, frequently manifested by fever, abdominal pain, and jaundice (Charcot’s triad) as well as confusion and septic shock (Reynolds’ pentad). It is due to an ascending bacterial infection of the biliary tree.[7]

Gallstones are a prevalent condition, with prevalence rates among American Indians reaching 60% to 70% and among white individuals in developed nations reaching 10% to 15%.[8] Gallstones were categorized into three types under the traditional classification scheme based on the amount of cholesterol they contain.[9] Cholesterol gallstones, formed from bile high in cholesterol, are the most common type. The second most common form is pigment gallstones, which are made of the breakdown of red blood cells and are black.[9] Mixed pigmented stones, comprising calcium substrates like calcium carbonate or calcium phosphate, cholesterol, and bile, represent the third type of gallstones.[9]

Understanding the risk factors associated with the development of gallstones is crucial due to their high prevalence. These risk factors include dietary habits, older age groups, female gender,[10], and obesity.[11], malabsorption.[12], and smoking, as there is a 19% relative increase among current smokers.[13]. Additionally, other comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus.[13], and hypertension.[14], are considered risk factors for developing gallstones. Understanding these risk factors is crucial as they often require surgical intervention.

Although cholecystectomy is a common treatment, it is not without potential complications. Intraoperative and postoperative complications of cholecystectomy are of utmost concern, particularly in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy.[15] These complications encompass potentially severe issues such as bleeding.[16], bowel injuries.[17], bile duct injuries.[18], and trocar site hernias.[19] Awareness of these risks and taking necessary precautions is crucial to ensure successful outcomes. Moreover, Gallstone spillage can significantly impact the prognosis and long-term quality of life. Despite initial beliefs that leaving gallstones in the peritoneal cavity is harmless, numerous complications have been reported.[20]

Postoperative complications typically manifest as general complaints, notably nausea, vomiting, and postoperative ileus. These are frequently observed following both general and local anesthesia. Furthermore, an infection following the surgery can cause pain and impede wound healing.[21] However, the cholecystectomy procedure can result in unique postoperative complications, such as stones in the common bile duct, resulting in gallstone pancreatitis. Shoulder pain may additionally be triggered by the irritant effects of carbon dioxide gas, peritoneal and diaphragmatic strain, and damage.[22,23,24]

Postoperative complications can be quite challenging, and one to look out for is the post-cholecystectomy syndrome (PCS). This term describes the emergence of a range of complex symptoms that become apparent after the surgery.[25] PCS can manifest with symptoms such as diarrhea due to bile acid malabsorption, right upper quadrant abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and intolerance to fatty foods.[26]

There is a lack of recent literature on this topic in Jordan, as far as knowledge goes. It is crucial to identify complications associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy, as they are often preventable with improved surgical techniques and healthcare. Therefore, this study aimed to thoroughly analyze the parameters that cause complications during and after laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Methodology

This study was approved by the Princess Basma Teaching Hospital research ethics committee with reference no MB 4719/2024/1. In this research, the influence of multiple parameters on intraoperative, postoperative complications, and post-cholecystectomy syndrome among patients who undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy was investigated. The type of data needed was quantitative and qualitative data, collected through primary and secondary means. A questionnaire was utilized for primary data collection, and data were collected via patient interviews, followed by a systematic review of the findings. For the secondary data collection, a thorough review of the existing research and literature was conducted. The available data will be carefully analyzed to ensure that our findings are well-informed and accurate.

Furthermore, both data collection methods will be used to maximize the reliability and accuracy of the findings, as using only one method won’t provide enough data for this type of research. The questionnaire was designed to collect data from patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy. It sought to gather data from patients by asking them questions during interviews. Three experts in the field tested the validity of the questionnaire, and their comments were taken into consideration. Then it was tested for reliability among 15 participants, and changes were made as required. During the interview, the following questions were asked about the patient: gender, age, obesity, smoking, drinking alcohol, suffering from malnutrition/malabsorption, peptic ulcer disease, esophagitis , type of food (fatty food, Fruits and vegetables, mix of fatty and fruits with vegetables), problems in the immune system ,coagulation disorders, chronic liver disease, type of gallstone (cholesterol, mixed, pigment), comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiac disease, cerebrovascular accident or stroke), type of gallbladder disease (acute cholecystitis, chronic cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis, Empyema, cholangitis), previous abdominal surgeries, psychological factors(Anxiety, depression, poor coping mechanisms), surgeon related factors (surgeon experience, surgical technique, surgeon judgment in complex cases), duration of surgery, need to convert to open surgery, intraoperative complications (biliary tract injuries , bleeding, gallstone spillage ,bowel or other organ injury ,trocar site hernia), early mobilization after surgery, Adequate pain management after surgery, adequate antibiotic prophylaxis, postoperative complications (nausea/vomiting, wound infection, pneumonia , or urinary tract infection), shoulder pain ,biliary complications (bile leaks), bleeding, blood clots (deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism), pancreatitis, postoperative ileus, other organ injury, post-cholecystectomy syndrome). The interviews with the patients were scheduled in primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare facilities. Before the interviews, consent and signatures were obtained from the patient on a consent form to ensure confidentiality. Moreover, the purpose of this research was clearly explained, and it was emphasized that any data collected would be used solely for research purposes. Additionally, the patient’s personal information would not be collected, nor would any information provided be disclosed. After completion of data collection, the data will be cleaned regarding specific parameters of inclusion and exclusion criteria to define the study population and enhance the validity. The inclusion criteria included patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy despite having comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiac diseases, or stroke), previous abdominal surgeries, and psychological factors, with any age and gender. The exclusion criteria included any patient who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy with malnutrition/malabsorption, peptic ulcer disease, esophagitis, problems in the immune system, coagulation disorders, and chronic liver disease.

Following the end of the data collection, 746 responses were collected. The data was then cleansed to ensure that all aspects met the criteria for inclusion. 722 replies met the inclusion criteria, whereas 24 conformed to the exclusion criteria. The data was then imported into the SPSS software to begin the analysis.

Results

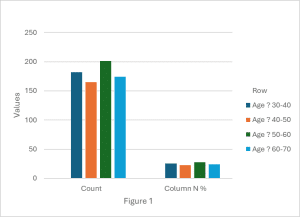

During this study, a total of 746 responses were obtained. Among these, 722 responses satisfied our inclusion criteria, while 24 responses met our exclusion criteria. The age distribution was as follows: 25.2% were aged 30-40, 22.9% were aged 40-50, 27.8% were aged 50-60, and 24.1% were aged 60-70. The mean age category was 3 (50-60 years), the median age category was 3, and the standard deviation was 1. The gender distribution was almost equal, with 51.1% female and 48.9% male participants.

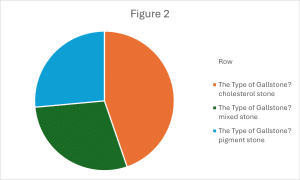

Regarding health indicators, 54.8% reported obesity, 50.8% were smokers, and 53.7% consumed alcohol. In terms of dietary habits, 68.3% consumed a mix of fatty foods and fruits/vegetables, while 31.4% consumed predominantly fatty foods. Comorbidities were prevalent, with 32.1% reporting hypertension, 21.7% reporting diabetes mellitus, 19.8% reporting cardiac disease, and 20.1% reporting no comorbidities. Gallbladder diseases were categorized as follows: chronic cholecystitis (30.1%), choledocholithiasis (27.0%), acute cholecystitis (21.6%), cholangitis (2.1%), and empyema (19.3%). Gallstones were primarily cholesterol stones (44.7%), mixed stones (28.8%), and pigment stones (26.5%). In addition, 60.4% of the participants had undergone previous abdominal surgeries, while a small minority (2.4%) reported experiencing psychological factors such as anxiety or depression (Table 1).

| Table 1 | Count | Column N % | |

| Age? | 30-40 | 182 | 25.2% |

| 40-50 | 165 | 22.9% | |

| 50-60 | 201 | 27.8% | |

| 60-70 | 174 | 24.1% | |

| AGE VAR (mean=3, median=3, standard deviation=1) | |||

| Gender? | Female | 369 | 51.1% |

| Male | 353 | 48.9% | |

| Obesity? | No | 326 | 45.2% |

| Yes | 396 | 54.8% | |

| Do you smoke? | No | 355 | 49.2% |

| Yes | 367 | 50.8% | |

| Do you drink Alcohol? | No | 334 | 46.3% |

| Yes | 388 | 53.7% | |

| What type of food you eat? | Fatty food | 227 | 31.4% |

| Fruits and vegetables | 2 | 0.3% | |

| Mix of fatty and Fruits with vegetables | 493 | 68.3% | |

| Do you have any Comorbidities? | Cardiac disease | 143 | 19.8% |

| Cardiac disease, CVA or stokes | 1 | 0.1% | |

| CVA or stokes | 33 | 4.6% | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 157 | 21.7% | |

| Hypertenstion | 232 | 32.1% | |

| Hypertension, Cardiac disease | 2 | 0.3% | |

| Hypertension, CVA or stokes | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Hypertenstion, Diabetes mellitus | 7 | 1.0% | |

| Hypertension, Diabetes mellitus, Cardiac disease | 1 | 0.1% | |

| No Comorbidities | 145 | 20.1% | |

| The type of Gallbladder disease? | Acute cholecystitis | 156 | 21.6% |

| Cholangitis | 15 | 2.1% | |

| Choledocholithiasis | 195 | 27.0% | |

| Chronic cholecystitis | 217 | 30.1% | |

| Empyema | 139 | 19.3% | |

| The Type of Gallstone? | Cholesterol stone | 323 | 44.7% |

| Mixed stone | 208 | 28.8% | |

| Pigment stone | 191 | 26.5% | |

| Previous abdominal surgeries? | No | 286 | 39.6% |

| Yes | 436 | 60.4% | |

| Any Psychological factors like Anxiety, depression, and poor coping mechanisms | No | 705 | 97.6% |

| Yes | 17 | 2.4% | |

Upon reviewing Table 2, it is evident that a strong level of confidence exists among the respondents concerning surgeon-related factors. Specifically, 98.5% of participants agree that their surgeon possesses sufficient experience, while only 1.5% disagree. Similarly, 98.5% of respondents believe that their surgeon employed the best surgical techniques, with just 1.5% expressing dissent. Furthermore, 98.2% of participants have trust in their surgeon’s judgment in complex cases, and only 1.8% have doubts. These findings collectively underscore a high degree of trust and satisfaction with the surgeons’ expertise, technique, and decision-making capabilities.

| Table 2 | Count | Column N % | |

| Surgeon-Related Factors (Do You Think Your Surgeon Has Enough Experience) | Agree | 711 | 98.5% |

| Disagree | 11 | 1.5% | |

| Surgeon-Related Factors (Do you think the surgeon used the best Surgical technique) | Agree | 711 | 98.5% |

| Disagree | 11 | 1.5% | |

| Surgeon-Related Factors (Do you think your surgeon will make the best judgment in complex cases) | Agree | 709 | 98.2% |

| Disagree | 13 | 1.8% | |

Table 3 provides an analysis of surgical outcomes and postoperative care, revealing several key findings. Most surgeries lasted for either 60 minutes (34.5%) or 45 minutes (31.3%), with a small portion extending to 90 minutes (16.8%) or longer. In 6.8% of cases, conversion to open surgery was necessary. Intraoperative complications were reported by 56.8% of patients, with gallstone spillage (35.5%) being the most common, followed by biliary tract injuries (16.6%). However, 43.2% of patients did not experience any complications. Postoperative care was generally well-handled, with 97.2% of patients mobilizing early and 97.5% receiving adequate pain management. Almost all patients (99.3%) received appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis. Postoperative complications varied, with shoulder pain being the most common (65.2%), followed by nausea and vomiting (9.7%), and biliary complications such as bile leaks (7.5%). Other less common complications included infections (4.6%), pancreatitis (2.8%), and deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism (0.6%).

| Table 3 | Count | Column N % | |

| Duration of surgery? | 120 min | 51 | 7.1% |

| 30 min | 75 | 10.4% | |

| 45 min | 226 | 31.3% | |

| 60 min | 249 | 34.5% | |

| 90 min | 121 | 16.8% | |

| The need to convert to open surgery? | No | 673 | 93.2% |

| Yes | 49 | 6.8% | |

| Intraoperative complications? | Biliary Tract Injuries | 120 | 16.6% |

| Bleeding | 20 | 2.8% | |

| Bowel or other organ injury | 8 | 1.1% | |

| Gallstone spillage | 256 | 35.5% | |

| No complications | 312 | 43.2% | |

| Trocar site hernia | 6 | 0.8% | |

| Postoperative Care Factors | Option 1 | 722 | 100.0% |

| Early mobilization after surgery? | No | 20 | 2.8% |

| Yes | 702 | 97.2% | |

| Adequate pain management after surgery? | No | 18 | 2.5% |

| Yes | 704 | 97.5% | |

| Adequate Antibiotic Prophylaxis? | No | 5 | 0.7% |

| Yes | 717 | 99.3% | |

| What complications did you suffer from post-laparoscopic operation? | Biliary complications (Bile leaks) | 54 | 7.5% |

| Biliary complications (Bile leaks), post-cholecystectomy syndrome | 2 | 0.3% | |

| Bleeding | 3 | 0.4% | |

| Blood clots (Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE)) | 4 | 0.6% | |

| Infection (Wound infection, pneumonia, or urinary tract infection) | 33 | 4.6% | |

| Infection (Wound infection, pneumonia, or urinary tract infection), post-cholecystectomy syndrome | 4 | 0.6% | |

| Nausea and vomiting | 70 | 9.7% | |

| Nausea and vomiting, Infection (Wound infection, pneumonia, or urinary tract infection) | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Nausea and vomiting, Infection (Wound infection, pneumonia, or urinary tract infection), and Shoulder pain | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Nausea and vomiting, Infection (Wound infection, pneumonia, or urinary tract infection), Shoulder pain, Postoperative ileus | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Nausea and vomiting, post-cholecystectomy syndrome | 11 | 1.5% | |

| Nausea and vomiting, Postoperative ileus | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Nausea and vomiting, Shoulder pain | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Other Organ Injury | 3 | 0.4% | |

| Pancreatitis | 20 | 2.8% | |

| post-cholecystectomy syndrome | 4 | 0.6% | |

| post-cholecystectomy syndrome, Blood clots (Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE)) | 3 | 0.4% | |

| Post-cholecystectomy syndrome, Pancreatitis | 10 | 1.4% | |

| Post-cholecystectomy syndrome, Postoperative ileus | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Postoperative ileus | 6 | 0.8% | |

| Shoulder pain | 471 | 65.2% | |

| Shoulder pain, Biliary complications (Bile leaks) | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Shoulder pain, post-cholecystectomy syndrome | 17 | 2.4% | |

After reviewing Table 4, the study examined post-cholecystectomy syndrome symptoms. 82.3% of respondents reported experiencing symptoms, while 17.7% did not. The most common symptoms were nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, reported by 19.5% of participants, followed by flatulence and diarrhea (16.2%), and flatulence alone (9.3%). Heartburn combined with diarrhea was reported by 7.2%, while nausea, vomiting, and flatulence were noted by 9.3% of respondents. Less frequently reported symptoms included jaundice (2.2%) and intermittent episodes of abdominal pain (0.3%). A small percentage of participants experienced complex symptom combinations, such as nausea, vomiting, heartburn, flatulence, diarrhea, and intermittent abdominal pain (0.1%). Overall, these findings indicate a significant prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms among patients following cholecystectomy, with diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting being the most common.

| Table 4 | Count | Column N % | |

| Have you suffered from post-cholecystectomy syndrome symptoms? | No | 128 | 17.7% |

| Yes | 594 | 82.3% | |

| What symptoms did you suffer from? | Diarrhea | 4 | 0.6% |

| Diarrhea, intermittent episodes of abdominal pain | 3 | 0.4% | |

| Diarrhea, jaundice | 16 | 2.2% | |

| Fatty food intolerance | 5 | 0.7% | |

| Fatty food intolerance, diarrhea | 14 | 1.9% | |

| Fatty food intolerance, flatulence | 20 | 2.8% | |

| Fatty food intolerance, heartburn | 12 | 1.7% | |

| Fatty food intolerance, intermittent episodes of abdominal pain | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Fatty food intolerance, jaundice | 8 | 1.1% | |

| Fatty food intolerance, nausea, vomiting | 25 | 3.5% | |

| Fatty food intolerance, nausea, vomiting, heartburn | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Fatty food intolerance, nausea, vomiting, heartburn, flatulence, diarrhea | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Fatty food intolerance, nausea, vomiting, heartburn, flatulence, diarrhea, intermittent episodes of abdominal pain | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Flatulence | 5 | 0.7% | |

| Flatulence, diarrhea | 117 | 16.2% | |

| Flatulence, intermittent episodes of abdominal pain | 4 | 0.6% | |

| Flatulence, jaundice | 7 | 1.0% | |

| Heartburn, diarrhea | 52 | 7.2% | |

| Heartburn, flatulence | 18 | 2.5% | |

| Heartburn, flatulence, intermittent episodes of abdominal pain | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heartburn, intermittent episodes of abdominal pain | 3 | 0.4% | |

| Heartburn, jaundice | 4 | 0.6% | |

| I don’t suffer from post-cholecystectomy syndrome | 126 | 17.5% | |

| intermittent episodes of abdominal pain | 2 | 0.3% | |

| Jaundice | 2 | 0.3% | |

| Jaundice, intermittent episodes of abdominal pain | 3 | 0.4% | |

| Nausea, vomiting | 13 | 1.8% | |

| Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea | 141 | 19.5% | |

| Nausea, vomiting, flatulence | 67 | 9.3% | |

| Nausea, vomiting, heartburn | 36 | 5.0% | |

| Nausea, vomiting, heartburn, flatulence, intermittent episodes of abdominal pain | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Nausea, vomiting, intermittent episodes of abdominal pain | 3 | 0.4% | |

| Nausea, vomiting, jaundice | 6 | 0.8% | |

Intraoperative complications

The analysis of intraoperative complications reveals significant associations with several patient demographics. Younger patients aged 30-40 exhibit the highest complication rates, with a Chi-Square value of 64.791 (p < 0.001) and a moderate effect size (Cramer’s V = 0.173). Obese patients also show a higher incidence of complications, particularly gallstone spillage, with a Chi-Square value of 30.097 (p < 0.001) and a moderate association strength (Phi = 0.204). Smoking is another contributing factor, with complications more prevalent among smokers (Chi-Square = 15.637, p = 0.008, Phi = 0.147). Alcohol consumption is associated with a modest increase in complications (Chi-Square = 11.336, p = 0.045, Phi = 0.125). These findings suggest that age, obesity, smoking, and alcohol use all significantly impact the risk of intraoperative complications, with varying strengths of association.

The analysis also revealed a significant association between intraoperative complications and several variables, providing insight into their impact on surgical outcomes. Patients who consume a mix of fatty foods and fruits/vegetables are more likely to experience complications such as gallstone spillage, with a significant Chi-Square value (X² = 17.961, p = 0.056) and a moderate effect size (Phi = 0.158). Cholesterol stones are most frequently associated with complications, particularly biliary tract injuries and gallstone spillage, as shown by a significant Chi-Square result (X² = 50.894, p < 0.001) and a moderate effect size (Cramer’s V = 0.188). Acute cholecystitis correlates strongly with higher complication rates, including biliary tract injuries and gallstone spillage, with a significant Chi-Square value (X² = 137.338, p < 0.001) and a strong effect size (Phi = 0.436). Comorbidities such as cardiac disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus are significantly associated with increased complication rates, as evidenced by significant Chi-Square values (e.g., X² = 84.693, p < 0.001) and moderate to strong effect sizes. Previous abdominal surgeries are linked to a higher rate of complications, particularly gallstone spillage and bleeding, with a highly significant Chi-Square result (X² = 404.782, p < 0.001) and a strong effect size (Phi = 0.749). Longer surgery durations are associated with increased complication rates, particularly bleeding and gallstone spillage, with a significant chi-squared value (X² = 20.297, p = 0.027) and a modest effect size (Cramer’s V = 0.112). These findings highlight the complex interplay between these factors and intraoperative complications, suggesting that both patient characteristics and procedural factors play critical roles in surgical outcomes.

Postoperative complications

The analysis of complications following laparoscopic operations reveals significant associations with several factors. Gender is notably associated with complications (X² = 51.116, p < 0.001), indicating that female patients face higher frequencies of issues like nausea, vomiting, and post-cholecystectomy syndrome, demonstrated by a moderate effect size (Phi = 0.266). Age also shows a significant relationship (X² = 117.019, p < 0.001), with older patients, particularly those aged 50-70, experiencing increased rates of nausea, vomiting, and postoperative ileus, reflected by a moderate effect size (Phi = 0.403). Alcohol consumption is linked to complications such as bleeding and infections (X² = 40.739, p = 0.009) with a moderate effect size (Phi = 0.238). The type of gallbladder disease significantly affects complication rates (X² = 165.227, p < 0.001), with acute cholecystitis strongly associated with bile leaks and infections, showing a robust effect size (Phi = 0.478). Also, comorbidities like cardiac disease, diabetes, and hypertension substantially influence complication rates (X² = 639.527, p < 0.001), with multiple comorbid conditions leading to a heightened risk of complications, as evidenced by a strong effect size (Phi = 0.941).

Furthermore, the analysis of data and Chi-Square tests demonstrates significant connections between post-laparoscopic operation complications and various factors. Patients with a history of previous abdominal surgeries are more likely to experience complications such as bile leaks and post-cholecystectomy syndrome (X² = 44.429, p = 0.003, Phi = 0.248), showing an increased risk associated with prior surgical history. Psychological factors, including anxiety, depression, and poor coping mechanisms, are strongly linked to complications like nausea and vomiting (X² = 133.983, p < 0.001, Phi = 0.431), highlighting the impact of mental health on postoperative outcomes. The duration of surgery significantly affects complication rates, with longer surgeries correlating with higher instances of nausea, infections, and post-operative ileus (X² = 172.711, p < 0.001, Phi = 0.489). Early post-surgery mobilization is linked to fewer complications (X² = 66.718, p < 0.001, Phi = 0.304), emphasizing the benefits of promoting movement. Additionally, effective pain management is crucial for reducing complications such as nausea and infections (X² = 85.793, p < 0.001, Phi = 0.345), highlighting its importance in the recovery process.

Post-cholecystectomy syndrome

The analysis of post-cholecystectomy syndrome symptoms across various demographic and health-related categories reveals several significant associations. Gender is notably associated with symptom reporting, with females experiencing a higher frequency of symptoms compared to males (X² = 92.642, p < 0.001). Age also plays a crucial role, as older individuals report a broader range of symptoms (X² = 195.592, p < 0.001). Obesity is linked to a different symptom profile, with obese individuals experiencing varied symptoms from non-obese individuals (X² = 80.055, p < 0.001). Smoking status further differentiates symptom experiences between smokers and non-smokers, showing distinct patterns (X² = 77.220, p < 0.001). Alcohol consumption influences the symptom profile, with alcoholics reporting different symptoms compared to non-drinkers (X² = 58.193, p = 0.003). The type of food consumed affects symptom patterns, as those eating a mix of fatty foods and fruits/vegetables report different symptoms than those eating predominantly fatty foods or fruits and vegetables (X² = 144.808, p < 0.001). Additionally, the type of gallstone (cholesterol, mixed, or pigment) is significantly associated with distinct symptom profiles (X² = 91.435, p = 0.014). Finally, the underlying gallbladder disease influences post-surgery symptom types and frequencies, indicating that different diseases (e.g., acute cholecystitis, cholangitis) are associated with specific symptom patterns.

Moreover, Psychological factors such as anxiety, depression, and poor coping mechanisms are correlated with a greater variety of symptoms, with a Pearson Chi-Square value of 105.907 (p < 0.001), indicating a strong link between psychological distress and the complexity of symptoms. The duration of the surgery also demonstrates a meaningful association with symptoms, with a Pearson Chi-Square value of 319.035 (p < 0.001), suggesting that longer surgeries may be associated with a wider range of post-surgical symptoms.

Discussion

Based on 722 eligible responses, this study provided comprehensive insights into the complications and outcomes of cholecystectomy, identifying several concerns. Key findings include certain intraoperative and postoperative concerns.

The largest age distribution of gallstone incidence was observed in older adults aged 50-60 due to a combination of factors (figure 1).

Hormonal changes contribute to this trend; after menopause, women experience declining estrogen levels, which increases the need for HRT (hormonal replacement therapy). All types of MHT (menopausal hormonal therapy), including Tibolone, have been associated with a higher risk of gallstones.[27] Additionally, reduced androgen levels in aging men affect bile composition, creating a more favorable environment for gallstone formation. New determinants such as testosterone levels and increased SHBG (sex hormone binding globulin) have shown direct and inverse associations with incident gallstone disease.[28] Finally, lifestyle factors like obesity, which is common in older adults, can alter bile composition and gallbladder function. There is a causal association between elevated BMI and increased risk of symptomatic gallstone disease.[29] Meanwhile, the gender distribution was nearly equal, with a slight increase in the percentage of females, attributable to the estrogen receptors on the liver, and the presence of endogenous estrogens causes cholesterol saturation in the bile, inhibition of chenodeoxycholic acid secretion, and increased cholic acid content.[30]

Cholesterol gallstones, the most prevalent type of gallstone disease, are on the rise, largely attributed to the global obesity epidemic associated with insulin resistance (Figure 2).[31]

Additionally, genetic factors play a significant role in gallstone formation. Several gene variants have been identified as predisposing individuals to gallstone development, the most notable being the p.D19H variant of the ABCG5/G8 gene.[32]

Intraoperative complications

Issues like gallstone spillage and bile duct injuries were common. Factors such as younger age, obesity, smoking, alcohol consumption, and consuming a mix of fatty foods and fruits/vegetables are more likely to experience higher complication rates.

Younger patients aged 30-40 often face a higher risk of intraoperative complications due to a complex interplay of factors. These patients frequently undergo more intricate surgical procedures, such as those necessitated by trauma or congenital anomalies, which can inherently increase the likelihood of complications.[33] Furthermore, younger individuals are more likely to present with conditions like obesity or autoimmune diseases, which can elevate surgical risk despite their generally lower burden of comorbidities compared to older patients.[35] Risky behaviors, including smoking and substance use, can further compromise recovery and exacerbate complication rates.[34] Additionally, the lack of routine health maintenance among younger individuals can lead to undiagnosed health issues that inadvertently increase intraoperative risks.[36]

Obesity significantly increases the risk of intraoperative complications due to a complex interplay of physiological and anatomical factors. Physiologically, obesity can lead to respiratory compromise, characterized by reduced lung capacity, increasing the risk of atelectasis and pneumonia.[37] Cardiovascular comorbidities, including hypertension, heart disease, and arrhythmias, elevate the likelihood of cardiac events during surgery.[38] Additionally, obesity is often associated with coagulation disorders, such as thrombophilia, which can increase the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE).[39] Impaired wound healing is another concern, as excess adipose tissue can reduce blood flow to the surgical site, resulting in delayed healing and a higher risk of infection.[38] Anatomically, obesity can hinder surgical access and visualization due to excessive adipose tissue, increasing the potential for errors and complications.[39] The increased weight of adipose tissue contributes to greater tissue trauma and blood loss during surgery.[37] Moreover, positioning obese patients on the operating table can be challenging, leading to risks of pressure ulcers and nerve damage.[40]

Smoking significantly increases the risk of intraoperative complications due to its deleterious effects on cardiovascular, respiratory, and wound healing systems. Cardio-vascularly, smoking contributes to atherosclerosis, increasing the likelihood of cardiac events such as myocardial infarction and stroke during surgery.[41] Nicotine-induced vasoconstriction further impairs blood flow, which can compromise wound healing and elevate the risk of tissue necrosis.[42] Respiratory, smoking damages lung tissue, leading to lower lung function and poor oxygen exchange, therefore raising the risk for conditions such as pneumonia and atelectasis.[45] Additionally, smoking weakens the immune system, heightening susceptibility to infections, including surgical site infections.[44] The combined consequences of smoking-induced blood flow restriction and delayed wound healing aggravate these risks by delaying the body’s natural healing mechanisms and raising the possibility of postoperative problems.[43]

Chronic alcohol abuse can lead to organ damage, impairing their ability to function properly during surgery. Excessive alcohol intake can cause damage to the liver, pancreas, heart, and brain. This damage can lead to a variety of health problems, including fatty liver disease, pancreatitis, cardiomyopathy, and brain damage.[46, 47, 48] Studies have demonstrated that unhealthy alcohol and drug use, both modifiable risk factors, are associated with significantly increased lengths of hospital stay.[49]

Previous upper abdominal surgeries are associated with a higher incidence of intraoperative and postoperative complications, resulting in significantly longer procedure times, increased postoperative pain, and elevated complication rates following laparoscopic cholecystectomy.[50] This increased risk is primarily due to the formation of adhesions, which are fibrous bands that can cause organs to adhere to each other or the abdominal wall, complicating the surgical field and making visualization and maneuvering more difficult.[51] Additionally, Scar tissue from previous surgeries can distort the normal anatomy of the abdominal cavity, complicating access and manipulation of internal structures and increasing the risk of injury to these structures.

Acute cholecystitis is associated with higher complication rates, including biliary tract injuries and gallstone spillage, primarily due to extensive inflammation and the formation of adhesions. This inflammation leads to increased oozing and makes the dissection of Calot’s triangle and identification of biliary anatomy more hazardous and challenging.[52]

Postoperative complications and post-cholecystectomy syndrome

Women are more prone to complications post-cholecystectomy than men, primarily due to hormonal factors. Estrogen increases cholesterol levels in bile and impairs gallbladder motility, enhancing susceptibility to gallstone formation.[54] This risk is further heightened by pregnancy and hormonal treatments like hormone replacement therapy and oral contraceptives.[54] Additionally, higher body fat percentages in women, influenced by the hormonal effects of adipose tissue, contribute to gallstone development.[53] Consequently, these factors lead to a higher incidence of complications such as nausea, vomiting, and post-cholecystectomy syndrome in female patients.

Older patients, particularly those aged 50-70, experience a heightened risk of complications following cholecystectomy due to several factors. The presence of comorbidities such as heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension is more common in the elderly, increasing the likelihood of surgical complications.[55] Additionally, elderly individuals are more susceptible to adverse effects from anesthesia, including respiratory depression and cardiac problems. They also face a greater risk of postoperative delirium and cognitive impairment, which can complicate recovery and lead to prolonged rehabilitation.[56] These factors contribute to an increased incidence of morbidity and mortality among older surgical patients.

Excessive alcohol consumption significantly increases the risk of complications following gallbladder removal. Alcohol strains the liver, potentially impairing bile production, which is crucial for digestion and can hinder post-surgical recovery.[57] It also weakens the immune system, making individuals more susceptible to infections.[58] Ethanol exposure impairs wound healing by disrupting the early inflammatory response, inhibiting wound closure, angiogenesis, and collagen production, and altering the protease balance at the wound site, all of which can delay recovery and heighten the risk of complications.[59] Additionally, alcohol interferes with gastrointestinal tract function, causing changes in esophageal and gastric motility that favor gastroesophageal reflux and potentially lead to reflux esophagitis, exacerbating symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, which can worsen after gallbladder removal and contribute to post-cholecystectomy complications.[60]

Anxiety acts as an intermediary in the relationship between personality traits and postoperative outcomes. Severe anxiety can partially account for the negative impact of certain personality traits, such as neuroticism, on postoperative recovery.[61] Patients with high levels of anxiety tend to have increased pain sensitivity and are more likely to suffer from gastrointestinal issues.[62] Furthermore, elevated anxiety levels can lead to a heightened focus on real sensations and side effects, potentially exacerbating postoperative discomfort and complications.[62]

Early mobilization is a critical component of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols, which are meant to mitigate the detrimental physiological effects of surgical stress and extended immobilization. By promoting early movement, early mobilization decreases the risk of postoperative complications, speeds up the recovery of functional walking ability, and improves various patient-reported outcomes. Additionally, it shortens hospital stays, which helps lower overall healthcare costs.[63]

The goal of postoperative pain control is to minimize the negative consequences of acute post-surgical pain and facilitate the patient’s seamless transition back to normal function. Tailoring postoperative pain management to a patient’s specific comorbidities and social factors is linked to reduced postoperative opioid consumption, shorter hospital stays, decreased preoperative anxiety, and fewer requests for sedative medications.[64]

Literature Review: Determinants of Intraoperative and Postoperative Complications in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is less invasive than open cholecystectomy and has better outcomes; it has replaced open cholecystectomy as the most common surgical procedure for treating cholelithiasis. However, complications can occur during and after the procedure. Based on recent research findings, this review investigates the factors that influence intraoperative and postoperative complications related to LC.

Intraoperative Complications

Anatomical variations in the gallbladder anatomy, such as dense adhesions and atypical configurations of the cystic duct and artery, pose enormous challenges during LC. Strasberg et al. (2008) and Memon et al. (2006) demonstrated that these anatomical anomalies are associated with increased rates of complications, primarily due to the heightened difficulty in accurately identifying and managing critical structures.[65,66] Moreover, a key factor influencing the incidence of intraoperative complications is the expertise level of the surgeon. According to Hobbs et al. (2006), surgeons with less experience are more prone to intraoperative complications, such as bile duct injuries, which emphasizes how important surgical skills and experience are in reducing risk.[67] Technical factors also critically influence intraoperative outcomes. Hwang et al. (2011) underscore that challenges such as suboptimal visualization due to intraoperative bleeding or inadequate insufflation pressure can significantly increase the risk of complications. Effective management of these technical issues is essential to reduce the incidence of adverse events.[68]

Postoperative Complications

One common postoperative consequence of laparoscopic cholecystectomy is bile leakage. Kuroda et al. (2012) report that the incidence of bile leakage is significantly influenced by the surgical technique used for cystic duct closure and the anatomical characteristics of the bile ducts. Early detection and proper intervention are necessary for the effective management of bile leakage to minimize negative consequences.[69] Notable concerns are postoperative infections, which include intra-abdominal infections and surgical site infections (SSI). Kiran et al. (2015) identify procedural contamination and the quality of postoperative wound care as key factors contributing to infection risk. Implementing prophylactic antibiotics and adherence to sterile techniques are crucial for minimizing infection rates.[70] Furthermore, a major problem is the variation in postoperative pain severity and recovery time. Mendez et al. (2017) clarified that these variables are affected by the degree of surgical dissection and management of analgesia, both of which are crucial in defining the course of a patient’s recovery.[71]

Risk Factors and Predictive Models

The risk of intraoperative and postoperative complications from laparoscopic cholecystectomy is known to be considerably increased by comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Tzeng et al. (2013) provide evidence that these comorbid conditions exacerbate complication rates, emphasizing the importance of thorough preoperative careful evaluation and management strategies to address these heightened risks.[72] Additionally, various predictive models have been developed to assess the likelihood of complications in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. For example, the Nassar risk score was employed to stratify patients based on their risk profiles, as described by Nassar et al. (2016). Such risk assessment tools are essential for optimizing preoperative planning and implementing targeted risk management strategies.[73]

Limitations and expectations

Despite the valuable insights and information provided, it is crucial to acknowledge and address the encountered limitations for the advancement of future research.

Firstly, while the sample size of 722 participants is reasonable, the generalizability and precision of the findings could be enhanced by including a larger and more diverse sample. A broader population representation across different demographics, health statuses, and geographic locations would strengthen the study’s conclusions. Furthermore, relying on self-reported data for certain health indicators (e.g., smoking, alcohol consumption) may introduce biases, such as recall bias and social desirability bias. This can occur when patients alter their responses due to concerns about how they are perceived by their doctors or others. However, this issue can be addressed by fostering a more friendly and trusting relationship between the doctor and the patient, as well as ensuring the patient’s privacy. In addition, the research’s cross-sectional design is more prone to recall bias. This can be lessened through various strategies such as follow-up questions, standardized questions, and cross-checking with other data sources. Although the study controls for several variables, there may be unmeasured factors that could affect the results, such as socioeconomic status, genetic predispositions, and quality of life. While the study acknowledges the role of psychological factors, the analysis may not fully capture the complexity and impact of mental health on surgical outcomes. Therefore, a more thorough examination could lead to a clearer understanding. The variability in surgical approaches could also influence outcomes.

The busy schedules of hospitals and medical staff can be seen as a limitation that could potentially impact data collection and patient care. Due to time constraints and high patient volumes, it was more challenging to reach patients, gather detailed information from them, and obtain their consent for participation on time. The findings of this study could be strengthened, and its limitations addressed by considering more parameters in future research. This could involve increasing sample diversity and ensuring more consistent data collection practices. These steps would enhance the robustness and applicability of future studies.

Finally, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is broadly considered a safe procedure and doesn’t have potential intraoperative and postoperative complications. Anatomical variations, skill level of the surgeon, technical considerations, and patient comorbidities are important factors determining these risks. Anatomical anomalies and technical challenges can significantly affect procedural outcomes, whereas surgeon experience and patient comorbidities further modulate the risk of complications. Continuous improvements in predictive modeling, surgical technique advancements, and optimization of patient management strategies are critical for alleviating these risks and improving both the safety and efficacy of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Sufficient research in these domains is vital to enhance surgical techniques and patient-care protocols.

Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the various factors that impact the outcomes of cholecystectomy. It examines patient demographics, health indicators, surgical processes, and postoperative challenges to gain a deep understanding. After analyzing the responses of 722 patients, key risk factors that were identified include obesity, smoking, alcohol use, and comorbidities, all of which significantly contribute to intraoperative and postoperative complications. The nature of gallbladder disease, especially acute cholecystitis and cholesterol stones, plays a crucial role in adverse outcomes. Furthermore, gender, age, prior surgeries, and psychological factors were strongly associated with increased postoperative risks such as nausea, vomiting, and post-cholecystectomy syndrome. These findings emphasize the importance of personalized preoperative assessments, proficient surgical planning, and individualized postoperative care to achieve the desired outcomes and reduce complications.

References

- Shaffer EA. Gallstone disease: Epidemiology of gallbladder stone disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20(6):981-996. doi.10.1016/j.bpg.2006.05.004 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- McSherry CK. Cholecystectomy: the gold standard. Am J Surg. 1989;158(3):174-178. doi.10.1016/0002-9610(89)90246-8 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hassler KR, Collins JT, Philip K, Jones MW. Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

- Kimura Y, Takada T, Kawarada Y, et al. Definitions, pathophysiology, and epidemiology of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14(1):15-26. doi.10.1007/s00534-006-1152-y PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kashyap S, Mathew G, King KC. Gallbladder Empyema. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls 2023. Gallbladder Empyema

- Copelan A, Kapoor BS. Choledocholithiasis: Diagnosis and Management. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;18(4):244-255. doi.10.1053/j.tvir.2015.07.008 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Virgile J, Marathi R. Cholangitis In: StatPearls 2024. Cholangitis

- Stinton LM, Myers RP, Shaffer EA. Epidemiology of gallstones. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39(2):157-169, vii. doi.10.1016/j.gtc.2010.02.003 PubMed | Crossref

- Jones MW, Weir CB, Ghassemzadeh S. Gallstones (cholelithiasis). In: StatPearls 2024. Gallstones (cholelithiasis)

- Pak M, Lindseth G. Risk Factors for Cholelithiasis. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2016;39(4):297-309. doi.10.1097/SGA.0000000000000235 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Parra-Landazury NM, Cordova-Gallardo J, Méndez-Sánchez N. Obesity and Gallstones. Visc Med. 2021;37(5):394-402. doi.10.1159/000515545 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Shebl FM, Andreotti G, Rashid A, et al. Diabetes in relation to biliary tract cancer and stones: a population-based study in Shanghai, China. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(1):115-119. doi.10.1038/sj.bjc.6605706 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Aune D, Vatten LJ, Boffetta P. Tobacco smoking and the risk of gallbladder disease. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(7):643-653. doi.10.1007/s10654-016-0124-z PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Zhang Y, Sun L, Wang X, Chen Z. The association between hypertension and the risk of gallstone disease: a cross-sectional study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22(1):138. doi.10.1186/s12876-022-02149-5 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hobbs MS, Mai Q, Knuiman MW, Fletcher DR, Ridout SC. Surgeon experience and trends in intraoperative complications in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2006;93(7):844-853. doi.10.1002/bjs.5333 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Suuronen S, Kivivuori A, Tuimala J, Paajanen H. Bleeding complications in cholecystectomy: a register study of over 22,000 cholecystectomies in Finland. BMC Surg. 2015;15(1):97. doi.10.1186/s12893-015-0085-2 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Schwartz MJ, Faiena I, Cinman N, et al. Laparoscopic bowel injury in retroperitoneal surgery: current incidence and outcomes. J Urol. 2010;184(2):589-594. doi.10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.133 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Christou N, Roux-David A, Naumann DN, et al. Bile duct injury during cholecystectomy: Necessity to learn how to do and interpret intraoperative cholangiography. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:637987. doi.10.3389/fmed.2021.637987 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Nofal MN, Yousef AJ, Hamdan FF, Oudat AH. Characteristics of trocar site hernia after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):2868. doi.10.1038/s41598-020-59721-w PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Woodfield JC, Rodgers M, Windsor JA. Peritoneal gallstones following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: incidence, complications, and management. Surg Endosc. 2004;18(8):1200-1207. doi.10.1007/s00464-003-8260-4 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Torpy JM, Burke AE, Glass RM. JAMA patient page. Postoperative infections. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2544. doi.10.1001/jama.303.24.2544 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Holte K, Kehlet H. Postoperative ileus: a preventable event. Br J Surg. 2000;87(11):1480-1493. doi.10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01595.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Donatsky AM, Bjerrum F, Gögenur I. Surgical techniques to minimize shoulder pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(7):2275-2282. doi.10.1007/s00464-012-2759-5 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kandil TS, El Hefnawy E. Shoulder pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Factors affecting the incidence and severity. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20(8):677-682. doi.10.1089/lap.2010.0112 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Shirah BH, Shirah HA, Zafar SH, Albeladi KB. Clinical patterns of postcholecystectomy syndrome. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2018;22(1):52-57. doi.10.14701/ahbps.2018.22.1.52 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Madacsy Z, Dubravcsik Z, Szepes Z. Postcholecystectomy syndrome: From pathophysiology to differential diagnosis – A critical review. Pancreat Disord Ther. 2015;5(3). Postcholecystectomy syndrome: From pathophysiology to differential diagnosis – A critical review doi.10.4172/2165-7092.1000162

- Yuk JS, Park JY. Menopausal hormone therapy increases the risk of gallstones: Health Insurance Database in South Korea (HISK)-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2023;18(12):e0294356. doi.10.1371/journal.pone.0294356 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Phelps T, Snyder E, Rodriguez E, Child H, Harvey P. The influence of biological sex and sex hormones on bile acid synthesis and cholesterol homeostasis. Biol Sex Differ. 2019;10(1):52. doi.10.1186/s13293-019-0265-3 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Stender S, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Elevated body mass index as a causal risk factor for symptomatic gallstone disease: A Mendelian randomization study. Hepatology. 2013;58(6):2133-2141. doi.10.1002/hep.26563 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cirillo DJ, Wallace RB, Rodabough RJ, et al. Effect of estrogen therapy on gallbladder disease. JAMA. 2005;293(3):330-339. doi.10.1001/jama.293.3.330 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Biddinger SB, Haas JT, Yu BB, et al. Hepatic insulin resistance directly promotes formation of cholesterol gallstones. Nat Med. 2008;14(7):778-782. doi.10.1038/nm1785 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rebholz C, Krawczyk M, Lammert F. Genetics of gallstone disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2018;48(7):e12935. doi.10.1111/eci.12935 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Stolzenberg L, Usman M, Huang A, et al. Intraoperative complications during orthopedic spinal surgery in a polypharmacy patient with multiple comorbidities. Cureus. 2023;15(6):e39949. doi.10.7759/cureus.39949 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Newell KA, Turka LA. Tolerance signatures in transplant recipients. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2015;20(4):400-405. doi.10.1097/MOT.0000000000000207 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Choban P, Flancbaum L. The impact of obesity on surgical outcomes: A review. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185(6):593-603. doi.10.1016/s1072-7515(97)00109-9 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Reichman DE, Greenberg JA. Reducing surgical site infections: A review. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2(4):212-221. Reducing surgical site infections: A review

- Ri M, Aikou S, Seto Y. Obesity as a surgical risk factor. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2017;2(1):13-21. doi.10.1002/ags3.12049 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bonaccorsi HA, Burns B. Perioperative cardiac management. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Perioperative cardiac management

- Madsen HJ, Gillette RA, Colborn KL, et al. The association between obesity and postoperative outcomes in a broad surgical population: A 7-year American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement analysis. Surgery. 2023;173(5):1213-1219. doi.10.1016/j.surg.2023.02.001 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Al-Mulhim AS, Al-Hussaini HA, Al-Jalal BA, Al-Moagal RO, Al-Najjar SA. Obesity disease and surgery. Int J Chronic Dis. 2014;2014:652341. doi.10.1155/2014/652341 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Elkhader BA, Abdulla AA, Ali Omer MA. Correlation of smoking and myocardial infarction among Sudanese male patients above 40 years of age. Pol J Radiol. 2016;81:138-140. doi.10.12659/PJR.894068 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hawn MT, Houston TK, Campagna EJ, et al. The attributable risk of smoking on surgical complications. Ann Surg. 2011;254(6):914-920. doi.10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822d7f81 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kean J. The effects of smoking on the wound healing process. J Wound Care. 2010;19(1):5-8. doi.10.12968/jowc.2010.19.1.46092 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Durand F, Berthelot P, Cazorla C, Farizon F, Lucht F. Smoking is a risk factor of organ/space surgical site infection in orthopaedic surgery with implant materials. Int Orthop. 2013;37(4):723-727. doi.10.1007/s00264-013-1814-8 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Baskaran V, Murray RL, Hunter A, Lim WS, McKeever TM. Effect of tobacco smoking on the risk of developing community-acquired pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0220204. doi.10.1371/journal.pone.0220204 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rocco A, Compare D, Angrisani D, Sanduzzi Zamparelli M, Nardone G. Alcoholic disease: Liver and beyond. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(40):14652-14659. doi.10.3748/wjg.v20.i40.14652 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Fernández-Solà J. The effects of ethanol on the heart: Alcoholic cardiomyopathy. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):572. doi.10.3390/nu12020572 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Nunes PT, Kipp BT, Reitz NL, Savage LM. Aging with alcohol-related brain damage: Critical brain circuits associated with cognitive dysfunction. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2019;148:101-168. doi.10.1016/bs.irn.2019.09.002 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kulshrestha S, Bunn C, Gonzalez R, Afshar M, Luchette FA, Baker MS. Unhealthy alcohol and drug use is associated with an increased length of stay and hospital cost in patients undergoing major upper gastrointestinal and pancreatic oncologic resections. Surgery. 2021;169(3):636-643. doi.10.1016/j.surg.2020.07.059 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Atasoy D, Aghayeva A, Sapcı İ, Bayraktar O, Cengiz TB, Baca B. Effects of prior abdominal surgery on laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Turk J Surg. 2018;34(3):217-220. doi.10.5152/turkjsurg.2017.3930 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Akyurek N, Salman B, Irkorucu O, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with previous abdominal surgery. JSLS. 2005;9(2):178-183. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with previous abdominal surgery

- Kitano S, Matsumoto T, Aramaki M, Kawano K. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9(5):534-537. doi.10.1007/s005340200069 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Tazuma S. Gallstone disease: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and classification of biliary stones (common bile duct and intrahepatic). Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20(6):1075-1083. doi.10.1016/j.bpg.2006.05.009 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Pak M, Lindseth G. Risk factors for cholelithiasis. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2016;39(4):297-309. doi.10.1097/SGA.0000000000000235 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Brollo PP, Muschitiello D, Calini G, Quattrin R, Bresadola V. Cholecystectomy in the elderly: Clinical outcomes and risk factors. Ann Ital Chir. 2022;93:160-167. Cholecystectomy in the elderly: Clinical outcomes and risk factors

- Strøm C, Rasmussen LS, Sieber FE. Should general anaesthesia be avoided in the elderly? Anaesthesia. 2014;69 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):35-44. doi.10.1111/anae.12493 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Osna NA, Donohue TM Jr, Kharbanda KK. Alcoholic liver disease: Pathogenesis and current management. Alcohol Res. 2017;38(2):147-161. Alcoholic liver disease: Pathogenesis and current management

- Sarkar D, Jung MK, Wang HJ. Alcohol and the immune system. Alcohol Res. 2015;37(2):153-155. Alcohol and the immune system

- Al-Nadaf AH, Awadallah A, Thiab S. Superior rat wound-healing activity of green synthesized silver nanoparticles from acetonitrile extract of Juglans regia L: Pellicle and leaves. Heliyon. 2024;10(2):e24473. doi.10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24473 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bode C, Bode JC. Alcohol’s role in gastrointestinal tract disorders. Alcohol Health Res World. 1997;21(1):76-83. Alcohol’s role in gastrointestinal tract disorders

- Ji W, Sang C, Zhang X, Zhu K, Bo L. Personality, preoperative anxiety, and postoperative outcomes: A review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19):12162 doi.10.3390/ijerph191912162 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Althagafi HM, Alghamdi FS, Alali MMS. Post-operative anticipation of outcome after cholecystectomy. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2017;69(7):2804-2808. doi.10.12816/0042569 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Tazreean R, Nelson G, Twomey R. Early mobilization in enhanced recovery after surgery pathways: current evidence and recent advancements. J Comp Eff Res. 2022;11(2):121-129. doi.10.2217/cer-2021-0258 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Horn R, Hendrix JM, Kramer J. Postoperative pain control. In: StatPearls 2024. Postoperative pain control

- Hassler KR, Collins JT, Philip K, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. In: StatPearls 2024. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy

- Talpur KAH, Laghari AA, Yousfani SA, Malik AM, Memon AI, Khan SA. Anatomical variations and congenital anomalies of extra hepatic biliary system encountered during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60(2):89-93. Anatomical variations and congenital anomalies of extra hepatic biliary system encountered during laparoscopic cholecystectomy

- Gani F, Cerullo M, Zhang X, et al. Effect of surgeon ‘experience’ with laparoscopy on postoperative outcomes after colorectal surgery. Surgery. 2017;162(4):880-890. doi.10.1016/j.surg.2017.06.018 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hobbs MS, Mai Q, Knuiman MW, Fletcher DR, Ridout SC. Surgeon experience and trends in intraoperative complications in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2006;93(7):844-853. doi.1002/bjs.5333 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ahmad F, Saunders RN, Lloyd GM, Lloyd DM, Robertson GSM. An algorithm for the management of bile leak following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89(1):51-56. doi.10.1308/003588407X160864 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Warren DK, Nickel KB, Wallace AE, et al. Risk factors for surgical site infection after cholecystectomy. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(2):ofx036. doi.10.1093/ofid/ofx036 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Barazanchi AWH, MacFater WS, Rahiri JL, et al. Evidence-based management of pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospect review update. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121(4):787-803. doi.10.1016/j.bja.2018.06.023 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Unalp-Arida A, Der JS, Ruhl CE. Longitudinal study of comorbidities and clinical outcomes in persons with gallstone disease using electronic health records. J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;27(12):2843-2856. doi.10.1007/s11605-023-05861-z PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Murphy MM, Shah SA, Simons JP, et al. Predicting major complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a simple risk score. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13(11):1929-1936. doi.10.1007/s11605-009-0979-3 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

Not reported

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Saed Bani Amer

Department of Medicine

Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

Email: saedbamer0000@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Lena Almemeh, Ghayda Wasfi

Department of Medicine

Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

Lina Badawneh, Abed Al-Rahman AL-Omari, Leen Abuzaid, Buthaina Fawwaz, Jana Al Saed

Department of Medicine

Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

Baraa Obeidat, Mohammad Al-Bashir

Department of General Surgery

Princess Basma Hospital, Jordan

Mohammad Al- Jammal, Sadam Abu-Aleigeh

Department of General Surgery

Princess Basma Hospital, Jordan

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Princess Basma Teaching Hospital research ethics committee with reference no MB 4719/2024/1.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Not reported

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Saed BA, Lina B, Lena A, et al. Key Predictors of Intraoperative and Postoperative Complications in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: Insights from a Jordanian Cross-Sectional Study. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622424. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622424 Crossref