Author Affiliations

Abstract

Background: Obesity is a multifactorial chronic disease, intensified by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, and linked to numerous comorbidities. Despite progress in pharmacological and surgical interventions, long-term obesity management remains inadequate, largely due to gaps in patient-centered care and limited use of shared decision-making (SDM).

Objective: To evaluate recent clinical trials and real-world interventions for obesity management in U.S. healthcare systems, with a focus on pharmacologic treatments, bariatric surgery, behavioral strategies, and SDM models.

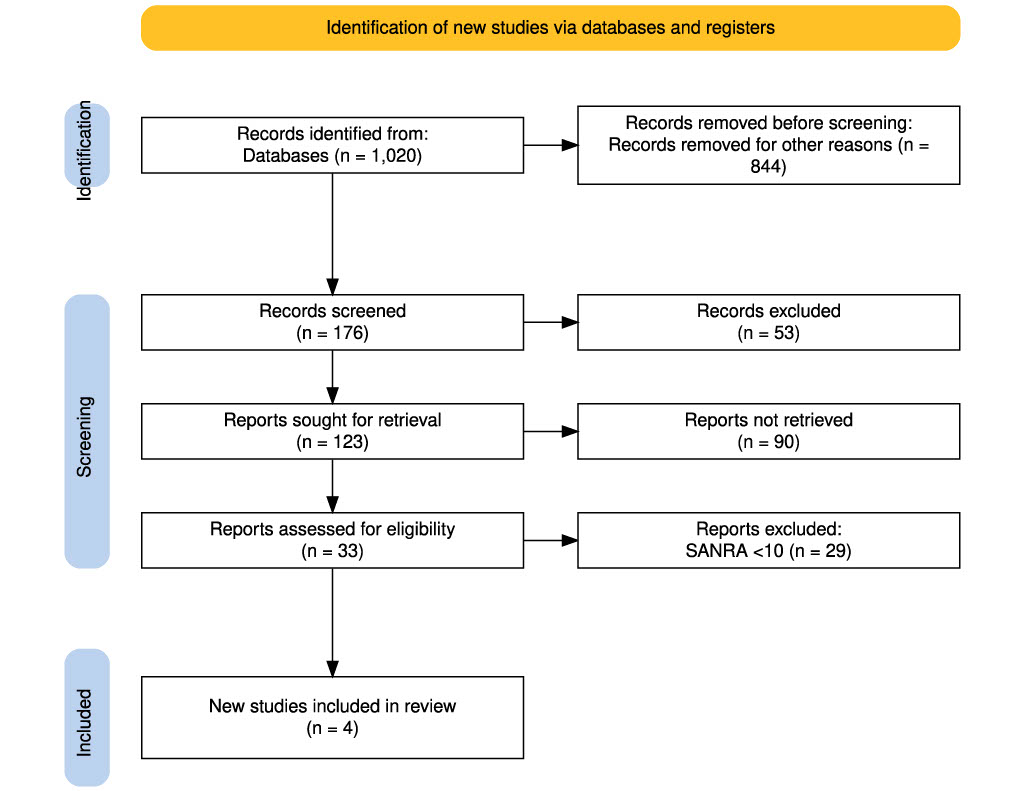

Methodology: A systematic literature review was conducted using databases like PubMed and Google Scholar, and all relevant articles were selected based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, four articles were included in this review. This review is carried out according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Results: Liraglutide 3.0 mg significantly improved weight and metabolic markers over 24 weeks. Bariatric surgery demonstrated superior long-term outcomes, including sustained weight loss and increased eligibility for renal transplantation. Preoperative teleprehabilitation in cardiac surgery candidates reduced major adverse cardiovascular events and improved quality of life. A network meta-analysis in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) showed the highest body mass index (BMI) and ovulation rate improvements with combined pharmacologic and lifestyle therapies.

Conclusion: Integrating pharmacological, surgical, and behavioral strategies with SDM enhances treatment adherence and outcomes. Sustainable obesity management requires personalized, evidence-based, and patient-inclusive care models.

Keywords

Obesity, Bariatric surgery, Coronavirus disease 2019, Polycystic ovary syndrome, Shared decision making, Body mass index.

Introduction

Obesity is a long-term and complex health condition marked by an excessive buildup of body fat, which can lead to serious health problems. It is commonly measured using BMI, where a BMI of 30 or higher indicates obesity. Obesity is further divided into Class I (BMI 30.0-34.9), Class II (35.0-39.9), and Class III (40.0 and above), also known as severe or morbid obesity. This condition is influenced by many factors, including genetics, behavior, environment, and metabolism. Poor diet, lack of physical activity, certain health conditions like hypothyroidism or PCOS, and medications such as corticosteroids and antipsychotics can all contribute to weight gain.[1-5] The health risks associated with obesity are numerous and severe. It increases the chances of developing heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, stroke, sleep apnea, joint problems like osteoarthritis, and several types of cancer. Obesity also negatively affects mental health, increasing the risk of depression and anxiety, and contributes to social stigma and reduced self-esteem.[6-8]

The COVID-19 pandemic further worsened the obesity crisis, especially among children. School closures and lockdowns disrupted daily routines, reduced access to healthy food and physical activity, and led to increased screen time and unhealthy eating habits. These changes have had long-term effects on children’s health, increasing their risk for obesity-related diseases.[9-14] At the same time, understanding the biological and molecular aspects of obesity has advanced. Research now explores how hormones, fat-regulating proteins (adipokines), and different types of fat tissue (like brown and beige fat) influence energy use and weight. These findings open new doors for treatments, but traditional strategies such as healthy eating, physical activity, behaviour change, and medications remain essential.[15-19]

Despite the availability of various treatment options, obesity rates remain high. One reason is the lack of patient-centered care. Many treatment plans do not fully consider the patient’s values, preferences, and life circumstances. This is where SDM can help. SDM is a collaborative process in which patients and healthcare providers work together to make informed treatment choices. It has shown positive results in managing other chronic diseases but is not widely used in obesity care due to time limits, lack of training, and systemic barriers.[20-24] Some U.S. programs like those by Kaiser Permanente, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) POWER Trials, and Duke Health’s pediatric initiatives have successfully included SDM in obesity care. These programs show that involving patients in their care can improve adherence, satisfaction, and outcomes.[25,26]

This mixed review aims to bring together current real-world applications of SDM in obesity care across the U.S. It will examine how SDM has been used in different healthcare models, what helps or hinders its success, and how it can be better implemented. The goal is to support more patient-focused, effective, and lasting obesity treatment strategies.

Methodology

A systematic literature search was conducted using the PubMed database to identify studies related to obesity and associated themes, including bariatric interventions, COVID-19, shared decision-making, and pharmacological treatments. The search strategy incorporated the terms “Obesity” AND (“Bariatric” OR “COVID” OR “Shared decision making” OR “Pharmacological treatment”), and filters were applied for Clinical Trials, Randomized Controlled Trials, and Human Studies. The search covered publications from January 1, 2023, to June 30, 2025.

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: clinical trials or randomized controlled trials, involved human subjects, were published in English, included both male and female participants, and fell within the specified publication window. Exclusion criteria comprised books, commentaries, editorials, letters, documents, book chapters, case reports, case series, literature reviews, non-English language articles, animal or in vitro studies, publications outside the time frame, and studies lacking a reported results section.

The initial search yielded 38,464 articles. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 1,020 records were downloaded from PubMed and Google Scholar. Before the screening phase, 844 records were removed for various reasons such as duplication, irrelevance, or technical issues. This left 176 records for screening, out of which 53 were excluded based on title and abstract review. The remaining 123 reports were sought for full-text retrieval; however, 90 could not be retrieved due to access limitations or unavailable full texts. This resulted in 33 full-text articles being assessed for eligibility. Of these, 29 studies were excluded due to a scale for the assessment of narrative review articles (SANRA) score of less than 10, indicating insufficient quality. Ultimately, 4 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the final review. This entire process is visually summarized in Figure 1, ensuring a transparent and systematic approach to study selection.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram showing the selection process of studies included in the review

Results

Liraglutide 3.0 mg drives substantial weight loss and metabolic improvements in just 24 weeks: This randomized study, demonstrated by Jessica Mok et al., involved 70 participants (mean age 47.6 years; 74% female), who were assigned to either liraglutide 3.0 mg daily plus lifestyle intervention or placebo plus lifestyle intervention. Baseline characteristics were similar between groups. Three participants (4.3%) were lost to follow-up, and a few discontinued treatments but continued providing data. Due to COVID-19-related restrictions and health issues, some participants missed final clinic visits. The primary intention-to-treat analysis included 31 liraglutide and 26 placebo participants. At 24 weeks, the liraglutide group showed a significantly greater percentage reduction in body weight compared to placebo (−8.82% vs −0.54%; P < .001), with a mean difference of −8.03% (95% CI, −10.39 to −5.66).

Per-protocol analysis (liraglutide: 30; placebo: 23) confirmed these findings (−9.05% vs −0.86%; adjusted mean difference −7.67%; P < .001). A sensitivity analysis using self-reported weights yielded similar results (−8.65% vs −0.14%; adjusted difference −8.29%). Additionally, 71.9% of participants in the liraglutide group lost at least 5% of their body weight, compared to only 8.8% in the placebo group.

Secondary outcomes favored liraglutide, showing greater total weight loss (−9.5 kg vs −0.4 kg), significant reduction in body fat (−4.9 kg), and improvements in fasting glucose, HbA1c, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol. Adverse events were more frequent in the liraglutide group (80% vs 57%), primarily gastrointestinal in nature. No serious adverse events, including cholecystitis, pancreatitis, or treatment-related deaths, were reported. Overall, liraglutide 3.0 mg was effective and well tolerated for weight loss.[27]

Bariatric surgery leads to superior outcomes in kidney transplant listing and weight reduction: In the study by Samuels et al., twenty patients were enrolled and randomized-12 to metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS) and 8 to medical management (MM). Nine patients (5 MBS, 4 MM) completed the baseline assessment and commenced treatment, forming the treated cohort, while eleven did not initiate therapy. Age, gender, BMI, weight, and excess weight did not differ significantly between the MBS and MM groups or between treated and untreated participants (all P > 0.10). All MM participants received dietary counseling focused on higher protein intake (40–50 g/day), reduced starches and sugars, increased physical activity, and strength training. One MM patient received semaglutide (0.25-0.5 mg).

The primary outcome, kidney transplant listing within 18 months, was not statistically significant: 2 MBS (40%) and 1 MM (25%) patients were listed (P > 0.99). However, total surveillance time was shorter for MBS (19 ± 9 months) compared to MM (60 ± 30 months; P = 0.021). At the latest follow-up, all 5 MBS patients and 1 MM patient (25%) were listed (P = 0.048). All MBS patients received a transplant versus none in the MM group (P = 0.008). Adverse events included two MBS patients needing emergency care (dehydration/syncope; missed dialysis). One MM patient died from COVID-19 at 4.5 years, and one MBS patient had a myocardial infarction at 3.75 years.

Follow-up was longer in MBS (mean 45 months) than MM (mean 30 months; P = 0.075). Adjusted weight loss was significantly greater in MBS (31 ± 13%) than MM (3 ± 7%; P = 0.046). Longitudinal models showed significantly greater declines in BMI and weight in MBS (interaction P ≤ 0.002), with meaningful effect sizes (R² ≥ 0.399), unlike MM (R² ≤ 0.0007).[28]

Effect of preoperative teleprehabilitation on major adverse cardiovascular events and functional outcomes in cardiac surgical candidates: In the study by Scheenstra et al., between May 2020 and August 2022, 394 patients were enrolled and randomized equally into intervention (n = 197) and control (n = 197) groups; one control patient withdrew consent. Baseline characteristics were balanced. The median preoperative period was shorter in the intervention group (12.6 vs. 14.8 weeks; P = 0.024), though ≥8-week prehabilitation duration did not differ significantly. The primary composite endpoint (MACE within 1-year post-surgery) occurred in 16.8% of the intervention group and 25.5% of the control group (difference: 8.8%; 95% CI: 0.7–16.8; P = 0.032). Unadjusted OR and HR were 0.59 (P = 0.037) and 0.62 (P = 0.037), respectively. Adjusted HR for the full cohort was 0.68 (P = 0.089). Stratified analysis showed a significant effect in non-transcatheter procedures (adjusted HR: 0.59; P = 0.044), but not in transcatheter/AF ablation cases (HR: 1.05; P = 0.94). Adjusted OR mirrored this pattern.

Subgroup benefits were observed in women (OR: 0.31; P = 0.030), patients with higher EuroSCORE II (OR: 0.49; P = 0.031), and cardiac surgery patients (OR: 0.49; P = 0.014). Quality of life at 12 months improved more in the intervention group (0.861 vs. 0.805; P = 0.002). Postoperative MACE was significantly lower in the intervention group (12.8% vs. 21.5%; P = 0.021), though preoperative MACE and hospital stay duration showed no group differences. Mortality was higher in the intervention group (n = 10 vs. 5), but not statistically significant. At baseline, 87.4% had at least one modifiable risk factor. Teleprehabilitation significantly reduced elevated pulmonary risk (P = 0.041) and smoking (3.2% vs. 14.2%; P = 0.001). Depression worsened preoperatively only in the control group (P = 0.027). Participation in intervention modules varied by risk factor, with the highest engagement in psychological support (71.1%) and functional training (66.3%).[29]

Weight reduction and ovulation therapies in obese women with PCOS: The study by González et al. primarily included women with PCOS and obesity, focusing on interventions aimed at either weight loss (using metformin, orlistat, GLP-1 receptor agonists, or sibutramine) or ovulation induction (using clomiphene). Interventions lasted 6 weeks to 12 months. Of the 95 RCTs included, 53% had high or unclear risk of bias, while randomization was adequate in 56%, and selective reporting was low risk in 79%. Heterogeneity was high for BMI (I² = 98%, τ² = 0.22) and moderate for ovulation (I² = 55%, τ² = 0.07), with no major inconsistencies observed.

BMI outcomes (60 RCTs, 5955 women) showed that all treatments except ovulation inducers significantly reduced BMI. The largest reductions were seen with diet plus weight-loss drugs (MD −2.61 kg/m²) and with added exercise (−2.35). GLP-1 RAs (−3.34), orlistat (−3.16), and metformin (−2.42) combined with lifestyle changes had the strongest effects in sensitivity analyses. For ovulation (25 RCTs, 2195 women), the greatest improvements were achieved with exercise plus diet combined with ovulation inducers (RR 7.15) or weight-loss drugs (RR 4.80), with consistent results in PCOS-only analyses. Regarding secondary outcomes, the greatest testosterone reduction was seen with exercise plus diet and weight-loss drugs (SMD −2.91). SHBG increased most with exercise, diet, and ovulation inducers (SMD 7.72), while androstenedione decreased most with the same combination (SMD −4.54). FAI showed non-significant improvements. FSH and LH levels increased significantly with exercise and weight-loss drugs (FSH SMD 2.19; LH SMD 2.52). Estradiol levels were reduced by weight-loss drugs (SMD −1.71), while progesterone levels showed no significant changes.[30]

Discussion

This systematic review highlights the breadth and effectiveness of diverse interventions for obesity, with emphasis on pharmacological therapies, bariatric procedures, behavioral strategies, and their implications in specific clinical contexts such as PCOS and cardiac surgery. Among the four studies included, each offered unique insights into obesity-related treatment pathways and their outcomes. The study by Mok et al.[27] demonstrated that liraglutide 3.0 mg, when combined with lifestyle intervention, significantly improves weight loss and metabolic parameters in a relatively short period of 24 weeks. The robust reductions in body weight, body fat, and cardiometabolic markers underscore liraglutide’s therapeutic potential in addressing obesity-related comorbidities. While adverse effects were more frequent in the intervention group, they were primarily mild and gastrointestinal in nature, reinforcing liraglutide’s favorable risk-benefit profile.

In contrast, the study by Samuels et al.[28] focused on a more intensive intervention, MBS, in patients preparing for kidney transplantation. MBS led to significantly greater weight loss, higher rates of transplant listing, and eventual transplantation compared to medical management. Despite the small sample size, this study supports MBS as a powerful tool for improving transplant candidacy in severely obese individuals, though it also highlighted procedural risks, including emergency visits and cardiovascular events.

Scheenstra et al.[29] Investigation into teleprehabilitation in cardiac surgery candidates offered a nonpharmacologic, digitally delivered intervention with meaningful cardiovascular benefits. The intervention reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), improved quality of life, and helped address modifiable risk factors, particularly smoking and pulmonary risk. Importantly, it showed subgroup-specific benefits, especially in women and patients undergoing traditional cardiac procedures. This supports the growing role of telehealth and multidisciplinary risk factor modification in high-risk surgical populations.

The comprehensive review by González et al.[30] evaluated pharmacologic and lifestyle interventions in obese women with PCOS. GLP-1 receptor agonists, metformin, and orlistat, particularly when combined with diet and exercise, produced substantial reductions in BMI and improvements in ovulation rates and hormonal profiles. The results emphasize the need for tailored, multifaceted treatment approaches in managing PCOS-related infertility, where weight management is a critical component.

Onyebuchi et al.[31] present compelling evidence for the efficacy of pharmacological and surgical approaches in obesity management. The introduction of advanced anti-obesity medications (AOMs), particularly GLP-1 receptor agonists such as semaglutide and tirzepatide, marks a transformative shift in obesity care. These agents have demonstrated clinically significant weight loss, improved glycemic control, and reduced cardiometabolic risk factors in both clinical trials and real-world settings. Their utility extends to patients who are either ineligible for or unwilling to undergo surgery, offering a less invasive but effective alternative.

Furthermore, bariatric surgical interventions, especially SG and RYGB, remain the most effective strategies for achieving substantial and sustained weight loss, along with remission of obesity-related comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes and obstructive sleep apnea. However, some studies emphasize that both pharmacological and surgical treatments must be supported by structured behavioral interventions to maintain long-term success. This reinforces the concept that obesity cannot be treated solely through biomedical interventions; it requires a holistic model of care that includes lifestyle change and psychological support.[32,33]

Varshini Reddeppa K et al.[34] shed light on a particularly vulnerable population: children affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Their findings confirm that lifestyle disruptions caused by school closures, social distancing, and lockdowns have led to a marked increase in childhood obesity rates. The primary contributing factors included reduced physical activity, increased screen time, irregular sleep, and poorer dietary habits. Importantly, the review highlights the long-term implications of these changes, including a heightened risk for developing type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and mental health disorders.

Together, these studies highlight the complex, multisystem nature of obesity and the need for personalized, evidence-based interventions. From surgical to pharmacologic and behavioral strategies, integrated care remains essential to optimizing outcomes in diverse obese populations.

Conclusion

Obesity is a complex, chronic condition requiring a personalized and multidisciplinary approach. This review highlights the effectiveness of newer pharmacological agents and bariatric procedures, particularly when combined with behavioral support. The COVID-19 pandemic has further intensified childhood obesity, necessitating urgent public health interventions. Advances in understanding the biological mechanisms of obesity offer promising pathways for targeted treatments. Additionally, incorporating shared decision-making enhances patient engagement, satisfaction, and outcomes. Integrating these clinical, biological, and patient-centered strategies is essential for improving the effectiveness and sustainability of obesity management.

References

- Rajiv KY, Zhang J, Xiaokun G. Biochemical Changes in Metabolic Syndrome. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622446. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622446 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mubashir A, Syed ZAS. Ranges of Body Mass Index in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Maximum and Minimum. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622438. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622438 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Saed BA, Lina B, Lena A, et al. Key Predictors of Intraoperative and Postoperative Complications in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: Insights from a Jordanian Cross-Sectional Study. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622424. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622424 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sakshi K, Raghavendraswamy K, Sijin W, Sandeep KM. Outcomes of Home Isolated COVID-19 Patients and Risk Factors Associated with the Adverse Outcomes: Longitudinal Retrospective Study in Shimoga, Karnataka. Medtigo J Med. 2025;3(2):e3062323. doi:10.63096/medtigo3062323 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Samatha A, Sonam SBV, Mansi S, Raziya BS, Shubham RS. A Comprehensive Review of Allium Cepa in Metabolic Syndrome Management. medtigo J Pharmacol. 2024;1(1):e3061111. doi:10.63096/medtigo3061111 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Glueck CJ, Goldenberg N. Characteristics of obesity in polycystic ovary syndrome: Etiology, treatment, and genetics. Metabolism. 2019;92:108-120. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2018.11.002 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hurt RT, Edakkanambeth Varayil J, Ebbert JO. New pharmacological treatments for the management of obesity. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;16(6):394. doi:10.1007/s11894-014-0394-0 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Salas-Parra RD, Smolkin C, Choksi S, Pryor AD. Bariatric Surgery: Current Trends and Newer Surgeries. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2024;34(4):609-626. doi:10.1016/j.giec.2024.06.005 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- King D. The future challenge of obesity. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):743-744. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61261-0 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cardel MI, Atkinson MA, Taveras EM, Holm JC, Kelly AS. Obesity Treatment Among Adolescents: A Review of Current Evidence and Future Directions. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(6):609-617. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0085 PubMed | Crossref | Google scholar

- O’Brien PE, Hindle A, Brennan L, et al. Long-Term Outcomes After Bariatric Surgery: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Weight Loss at 10 or More Years for All Bariatric Procedures and a Single-Centre Review of 20-Year Outcomes After Adjustable Gastric Banding. Obes Surg. 2019;29(1):3-14. doi:10.1007/s11695-018-3525-0 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Buchwald H. The evolution of metabolic/bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2014;24(8):1126-1135. doi:10.1007/s11695-014-1354-3 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ashruta P. Health Disparities and COVID-19: A Commentary. medtigo J Med. 2025;3(1):e30623132. doi:10.63096/medtigo30623132 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Panchal JH, Prakash V. A Study of Laparoscopic (Simple or Complex) Cholecystectomy with or without ERCP and CBD Stenting Associated with Other General, Bariatric, Gynaecological, and Renal Surgical Procedures in a Single Session. medtigo J Med. 2025;3(2):e30623225. doi:10.63096/medtigo30623225 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Shah H, Said M, Arif U, Asaf S, Shakoor A, Farooq M. Challenges Faced by Patients After Bariatric Surgery: A Qualitative Study in Swat, KPK, Pakistan. medtigo J Med. 2025;3(1):e30623137. doi:10.63096/medtigo30623137 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mubashir A, Syed ZAS. Ranges of Body Mass Index in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Maximum and Minimum. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622438. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622438 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Shafi MM, Umair M, Noor MH, et al. Scraping the Tip of the Iceberg: Prevalence of Undiagnosed Hypertension Among Patients Presenting to the OPD of Public Tertiary Hospitals, Rawalpindi. medtigo J Med. 2025;3(2):e30623217. doi:10.63096/medtigo30623217 Crossref

- Magaji A, Jimoh OY, Joel Y, Rubiyamisumma DK. Role of Marine Natural Products in Combating SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. medtigo J Pharmacol. 2025;2(2):e3061222. doi:10.63096/medtigo3061222 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Masiello MG, Ricci E. Pandemic Public Health Recommendations from 2003 to 2017: Why Were We Not Prepared for SARS-CoV-2? medtigo J Med. 2025;3(2):e3062325. doi:10.63096/medtigo3062325 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sakshi K, Raghavendraswamy K, Sijin W, Sandeep KM. Outcomes of Home Isolated COVID-19 Patients and Risk Factors Associated with the Adverse Outcomes: Longitudinal Retrospective Study in Shimoga, Karnataka. medtigo J Med. 2025;3(2):e3062323. doi:10.63096/medtigo3062323 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Olutade-Babatunde O, van der Kwaak A, Tejan YS, Christian N. Promising Strategies and Practices to Promote Adolescent Mothers’ Health-Seeking Behaviour and Utilization of Maternal Healthcare Services in Nigeria. medtigo J Med. 2025;3(1):e3062315. doi:10.63096/medtigo3062315 Crossref

- Ogochukwu O. The Perception of Teachers on the Impact of COVID-19 on the Academic Performance of Students in Science Subjects in Nnewi North Education Zone. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622456. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622456 Crossref

- Isabelle B-S, Fatima F. A Literature Review: Impact of COVID-19 on Lebanon. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622429. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622429 Crossref

- Ummar G, Sabahat Z. C, Laraib H, Malaika M. A. The Comparison Between Smartphone Addiction and Headache Among Males and Females. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622419. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622419 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ogu AG, Isabu CA. Socio-Demographic Determinants of Prevalence of Puerperal Psychosis Among Postpartum Mothers Attending Neuropsychiatric Hospital Remigio, Portharcourt. medtigo J Neurol Psychiatry. 2024;1(1):e3084119.

doi:10.63096/medtigo3084119 Crossref | Google Scholar - Fabeeha S, Tooba U, Rabia A, Afrah H, Ghazala U. Challenges Faced by the Undergraduate Medical Students Due to Online Learning During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comparison between the Public and Private Sector. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622416. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622416 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mok J, Adeleke MO, Brown A, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Liraglutide, 3.0 mg, Once Daily vs Placebo in Patients With Poor Weight Loss Following Metabolic Surgery: The BARI-OPTIMISE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2023;158(10):1003-1011. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2023.2930 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Samuels JM, English W, Birdwell KA, et al. Medical and Surgical Weight Loss as a Pathway to Renal Transplant Listing. Am Surg. 2025;91(1):99-106. doi:10.1177/00031348241275714 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Scheenstra B, van Susante L, Bongers BC, et al. The Effect of Teleprehabilitation on Adverse Events After Elective Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2025;85(8):788-800. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2024.10.064 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ruiz-González D, Cavero-Redondo I, Hernández-Martínez A, et al. Comparative efficacy of exercise, diet and/or pharmacological interventions on BMI, ovulation, and hormonal profile in reproductive-aged women with overweight or obesity: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2024;30(4):472-487. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmae008 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Chinu O, Oluchi U-O, Chuba SJ. Bariatric Medicine: A Comparative Review of Current Trends in Obesity Management. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(3):e3062250. doi:10.63096/medtigo3062250 Crossref

- Chinua O, Adesewa AR, Kelvin A, et al. Chemobiology of Obesity and Advances in Bariatrics: A Systematic Review. medtigo J Med. 2025;3(1):e30623130. doi:10.63096/medtigo30623130 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Nnonyelu C, Onyebuchi C, Okeke HN, et al. Shared Decision-Making and Obesity Management Across Healthcare Models in the United States: A Narrative Review. medtigo J Med. 2025;3(2):e30623219. doi:10.63096/medtigo30623219 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Varshini Reddeppa K, James JB, Afrin F, Roopali PK, Darshan Kiran K, Ashutosh J. Rise of Obesity in Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic and its Effects on their Health: A Systematic Literature Review. medtigo J Med. 2025;3(1):e30623115. doi:10.63096/medtigo30623115 Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

No funding

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Samatha Ampeti, PhD

Department of Pharmacology

Kakatiya University, University College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Warangal, TS, India

Email: ampetisamatha9@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Mansi Srivastava, Raziya Begum Sheikh, Patel Nirali Kirankumar, Shubham Ravindra Sali

Independent Researcher, Department of Content

medtigo India Pvt Ltd, Pune, India

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest Statement

None

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Mansi S, Samatha A, Raziya BS, Patel NK, Shubham RS. Integrated Approaches to Obesity Management: Pharmacological Advances, Pandemic Challenges, and the Role of Shared Decision-Making. medtigo J Pharmacol. 2025;2(3):e3061232. doi:10.63096/medtigo3061232 Crossref