Author Affiliations

Abstract

Postpartum hemorrhage is one of the leading causes of maternal deaths during childbirth globally, especially in under developed countries. Kenya’s maternal deaths are estimated at 510 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, significantly higher than the average for developed countries. This research investigates the incidences of postpartum hemorrhage in a Kenyan hospital, Ongata Rongai sub-county hospital (ORSCH), found in Kajiado county. The research’s objectives include: To know socio-demographic data of the participants, to assess the patients’ factors associated with postpartum hemorrhage among women delivering at ORSCH, and to assess the health service factors associated with postpartum hemorrhage among women delivering at ORSCH. The study takes the form of a hospital-based cross-sectional research study that uses sampling to get study participants. Statistical methods are used to obtain an ample study sample for the research. The study also observes ethical research guidelines, such as obtaining informed consent from study participants. A formal write-up to the department of clinical medicine at KMTC headquarters, Nairobi, was made requesting to undertake this research project. The head of the department agreed to the request and offered a formal introductory letter to the ORSCH, requesting the institution to allow participation in this research. Furthermore, a permit license was obtained from the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI), granting permission to do the research. Throughout the research, patients’ confidentiality was maintained by using patient numbers and file numbers and not using patients’ names. Additionally, the data were anonymized once collected to further observe the confidentiality principle. The information obtained was further accessible to only the doctor, nurses, and clinical officers who were taking care of the patients.

Keywords

Postpartum hemorrhage, Ongata Rongai sub-county hospital, Pregnancy, Delivery, Prevalence.

Introduction

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is defined as the loss of more than 500 ml of blood after a normal delivery and is one of the leading causes of maternal death globally. The incidence of PPH is estimated to be 6%, with a higher burden experienced in developing countries.[1-3] Sub-Saharan Africa has a high magnitude, with 10.5% of all maternal deaths attributed to PPH. In Kenya, PPH is responsible for nearly 34% of all maternal deaths.[4-8] This percentage, therefore, contributes a significant proportion to the country’s maternal mortality of 510 deaths per 100,000 live births. PPH is critical since it may lead to or exacerbate the risk of maternal complications such as adult respiratory syndrome, hepatic failure, renal failure, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and hypovolemic shock. Causes of PPH may be related to patterns associated with obstetrical practice, such as inattentive labor management or inappropriate labor induction. For example, protracted labor could lead to chorioamnionitis, a causative factor for uterine atony.

In Kenya, PPH contributes to about 14% of all maternal deaths (World health organization (WHO), 2020). The universal health coverage focuses on improving the health of women to reduce the maternal mortality rate in Kenya. Maternal mortality in Kenya accounts for 500/100,000 live births, with PPH contributing the highest percentage, with uterine atony being the major factor contributing to PPH.[4-10] There are very few studies on the incidence of PPH in Kenya and its influence on maternal deaths.[8] researched potential management strategies for the condition in a clinical setting. Therefore, the ministry of health under the instructions of the Kenyan government, has set up clinical guideline that are followed by all health facilities during the natal period in collaboration with non-governmental organizations and private hospitals, to offer quality health services to all pregnant women with the aim of reducing chances for complications post-delivery like PPH.

Despite all these efforts by Kenyan government, PPH remains a burden to the well-being of pregnant women across various counties in Kenya and Kajiado county is not an exception; therefore, the need for this study to determine the incidence and factors associated with PPH. The results of this study drew attention for possible answers to this problem. This study, therefore, sought to provide a concise description of the incidence of PPH in a local hospital, Ongata Rongai sub-county Hospital in Kajiado county. It also aimed to provide an overview of factors that influence this incidence.

The lack of up-to-date empirical evidence on the incidence of PPH impedes the formation and execution of strategic policies to curb maternal mortality attributed to it. Therefore, this study is essential due to its significant role in identifying at-risk populations in the hospital setting and to help people reduce morbidity and mortality due to PPH.

Research Questions: The study’s research questions are:

- What is the incidence of PPH in ORSCH?

- What are the patients’ factors associated with PPH among women delivering at ORSCH?

- What are the health service factors associated with PPH among women delivering at ORSCH?

- What is the socio-demographic data of participants?

Broad Objectives: This study aims to establish the incidence of PPH in ORSCH.

Specific Objectives:

- To know the socio-demographic data of the women delivering at ORSCH.

- To assess the patients’ factors associated with PPH among women delivering at

- To assess the health service factors associated with PPH among women delivering at ORSCH.

Scope and Limitations: The study was limited to the maternal population within ORSCH for the study period; therefore, these excluded cases of PPH that were reported within the hospital’s vicinity but were not attended to within the hospital. However, the small sample population might have led to a large margin of error.

Methodology

This chapter describes the various methods used in the study to collect and present the information required alongside describing the area and population to be studied.

Study design: The study was a descriptive cross-sectional study design.

Study area: ORSCH is a Level 4 hospital located in Rongai town, Kajiado County. Kajiado county has a population of about 1,117,840 persons as per the 2019 Kenya national bureau of statistics (KBNS) report, with 557,098 being males and 560,704 recorded as females, while about 38 were intersex. Rongai town is in Kajiado North, Kajiado County, and contributes to a population of 172,569 people out of the total population in Kajiado County. The females make about 87,592 persons while the males make about 84,969 as per the KBNS report of 2019. The town covers an area of about 17 square kilometers.[11-18]

Ongata Rongai has an average diurnal temperature range of 27 degrees Celsius to 17 degrees Celsius per annum. About 70 percent of the people in this county practice agriculture, tourism, livestock herding, and pastoralism. Products made from livestock include beef, dairy, poultry, skins, and hides. Due to the county’s arid climate, agriculture is performed through greenhouses and irrigation, with horticulture being the primary activity. The other remaining 30 percent work in the civil sector and as businesspeople. The people of this region are thus mainly Maasai speakers, who speak the Maasai language.[17,18] However, the place has grown to a metropolitan area comprising various communities that interact with the Swahili language. These people practice male circumcision as a rite of passage. The majority of the population are Christians who worship Enkai.

Study population: The study focused on the mothers who presented to ORSCH from Kajiado county with PPHS. Most people in Rongai are small-scale subsistence farmers, earning less than 200 Kenyan shillings per day, with the main food crop being maize.

Inclusion criteria: The study included maternal births reported within the hospital during the study period and were restricted to cases of PPH.

Exclusion criteria: The study excluded maternal complications not associated with PPH, cases of PPH that the hospital did not handle, and cases of PPH before the commencement of the study.

Dependent variable: The study’s dependent variable was PPH.

Independent variables: The study’s independent variables were factors that influence PPH and include antepartum hemorrhage, retained placenta, stillbirth, multiple gestations, medical induction of labor, precipitate labor, abnormally long labor, chorioamnionitis, polyhydramnios, previous cesarean delivery, uterine fibroids, diabetes mellitus, hypertensive disease of pregnancy, mode of delivery and age.

Sampling techniques: The study used a sampling technique. To determine the incidences of PPH, a systematic sampling method using inpatient numbers was used. To determine the socio-demographic, patient and the hospital factors a questionnaire was distributed among the patients.

Sample size determination: The sample size was determined using Morgan and R. V. Krejcie’s table from the specified population and was limited to mothers diagnosed with PPH at ORSCH. The target population was 40 mothers who visit ORSCH.

Development of data collection tool: The study used a document analysis technique to analyze the patient’s file. The documents used had a bio-information section and a variables section. The study also employed the use of questionnaires in collecting data.

Data collection: A questionnaire was administered to a sample of 5 patients per week with the consent of the hospital administration. A record review tool was used to collect relevant information about hospital factors to determine the prevalence. Data was collected for two months since the hospital works every day.

Data quality control: The questionnaire was pretested in a similar population of ORSCH, Kajiado county, to ensure the clarity of questions. At the end of the interview, the questionnaire was checked to ensure all questions were completed, and participants were randomly chosen to eliminate bias. The data was collected for a period of two months to ensure reliability.

Data analysis and presentation: The study’s results were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The data for incidences and the factors were analyzed using Microsoft Excel manually and interpreted into averages and percentages and presented in tables and pie charts.

Ethics considerations: A formal write-up to the department of clinical medicine at Kenya medical training college (KMTC) headquarters, Nairobi was made requesting to undertake this research project. The head of the department agreed to the request and offered a formal introductory letter to the ORSCH, requesting the institution to allow the participation in this research. Furthermore, a permit license was obtained from NACOSTI, granting permission to do the research.[18] Throughout the research, patients’ confidentiality was maintained by using inpatient numbers and file numbers and not using patients’ names. Additionally, the data were anonymized once collected to observe the confidentiality principle further. The information obtained was further accessible to only the doctor, nurses, and clinical officers who were taking care of the patients. The authors informed participants about the study’s purpose and obtained their informed consent before administering the questionnaires. They were further informed that if they felt uncomfortable at any point during the study, they could discontinue at any point.

Results

Results of data collection, analysis, and interpretation are presented in this chapter using pie charts, tables, histograms, line graphs, and simple statements. A calculator was used for data analysis. Questionnaires were used to interview a total of 36 mothers.

Respondent’s demographic data: The study’s data show that the age ranges from 36 to 45 (41.7%) is the most affected. This is evident by the 15 mothers out of the total 36 interviewed, and the majority of the interviewed women (31 out of the total of 36 interviewed) were married, accounting for about 86.1% and belonging to the Muslim faith. The tribe with the most participants belonged to the Agikuyu, which had 18 (50.0%) mothers. Additionally, many participants had never attended school, making the bulk of them peasants by profession. Out of 36, 15(41.8%) mothers never attended school, which contributed to 18 (50%) of them being peasants by profession.

| Variable | Frequency | Percentages |

| (Age in years)

19-25 |

10 | 27.8 |

| 26-35 | 11 | 30.6 |

| 36-45 | 15 | 41.7 |

| (Marital status)

Married |

31 | 86.1 |

| Unmarried | 5 | 13.9 |

| (Religion)

Muslims |

15 | 41.7 |

| Protestants | 11 | 30.6 |

| Catholics | 9 | 25 |

| Others | 1 | 2.8 |

| (Tribe)

Agikuyu |

18 | 50.0 |

| Luo | 10 | 27.8 |

| Kalenjin | 4 | 11.1 |

| Maasai | 3 | 8.3 |

| Others | 1 | 2.8 |

| (Occupation)

Peasants |

18 | 50.0 |

| Traders | 10 | 27.8 |

| Teachers | 4 | 11.1 |

| Unemployed | 4 | 11.1 |

| (Education level)

Nil |

15 | 41.7 |

| Primary | 10 | 27.8 |

| Secondary | 4 | 11.1 |

| Tertiary college | 3 | 8.3 |

| University | 4 | 11.1 |

Table 1: Displays the sociodemographic details of the women who had PPH diagnoses in ORSCH (n=36)

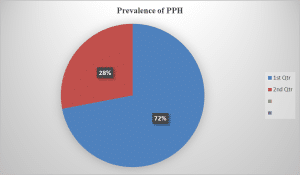

Prevalence of PPH in ORSCH: Only 10 (28%) of the moms who responded to the survey had a favorable opinion of PPH, compared to twenty-six (72%) who had a negative opinion.

Figure 1: Showing the prevalence of PPH among women

Patient factors associated with PPH among women delivering in ORSCH: More than 16 out of 36 of the mothers who made the biggest contribution had had multiple births. Most of them blamed numerous pregnancies, which were the cause of PPH among sixteen mothers, and 32 out of 36 of the mothers had given birth in a hospital.

| Variable | Frequency | Percentages |

| (Number of deliveries)

1 |

9 | 25 |

| 2 | 4 | 11.1 |

| 3 | 4 | 11.1 |

| 4 and above | 19 | 52.8 |

| (Associated factors)

Multiple pregnancy |

18 | 50.0 |

| Previous PPH | 9 | 25.0 |

| APH | 6 | 16.7 |

| Don’t know | 3 | 8.3 |

| (Place of delivery)

hospital |

30 | 83.3 |

| home | 4 | 11.1 |

| Others (eg, in a car) | 2 | 5.6 |

Table 2: Showing patient factors

Hospital factors associated with PPH among women delivering in ORSCH: Most moms (61%) had their babies by cesarean section. Induced labor was one of the hospital’s correlations with PPH, coming in at number 14 (38.9%), and most women received nursing assistance at number 15 (41.7%).

| Variable | Frequency | Percentages

|

| (Patient mode of delivery)

C/S |

22 | 61.1 |

| Spontaneous vaginal delivery (SVD) | 14 | 38.9 |

| (Assistant delivery)

Doctor |

15 | 41.7 |

| Nurse/midwife | 10 | 27.8 |

| Clinical officer | 6 | 16.7 |

| Traditional assistant | 5 | 13.9 |

| (Associated factors)

Induced labor |

14 | 38.9 |

| Instrumental delivery | 1 | 2.8 |

| Retained placental products | 4 | 11.1 |

| Episiotomies | 9 | 25.0 |

| Uterine atony | 4 | 11.1 |

| Perinium tear | 4 | 11.1 |

Table 3: Showing hospital factors

Discussion

The majority of mothers were negative about PPH (26 mothers out of 36); hence, 30 (83.3%) out of 36 had delivered from hospitals, while four had delivered from home, and two in a car. Ten mothers were positive about PPH, which translates to 28% of the total 36 mothers interviewed. Most deliveries were performed via caesarian section 22 with the help of doctors 15 (41.7%), and the remaining 14 spontaneous vaginal births were helped by midwives in 10 (27.8%), clinical officers in 6 (16.7%), and traditional assistants in 5 (13.9%) of the cases. In addition to maternal age and mom’s parity, induced labor came in at number 14 (38.9%) among hospital-related variables for PPH, followed by episiotomies at number 9 (25.0%). Induced labor and cesarean sections were the main causes of PPH in mothers, which is consistent with the results of earlier investigations. [4-11,13, 16] This might be due to doctors managing crises and difficult cases in an effort to preserve one or two lives (mother and the baby).

Multiple pregnancies, which ranked 18 (50.0%), and past PPH histories, which ranked 9 (25.0%), were the two main causes of PPH in women. These results are comparable to those of.[1-3,8,12,15] since more than one fetus tends to overstretch the mother’s womb, losing its tonicity and failing to stop bleeding after delivery. Mothers with parties higher than or equal to four 19 (52.8%) were most impacted. Since they believe they are accustomed to giving birth, multi-gravid mothers may have neglected antenatal care (ANC) services when they could have identified concerns for PPH. Delivery can also be complicated by where the mother gives birth. According to my research, 30 (83.3%) of moms gave birth at health centers, compared to 4 (11.1%) who gave birth at home and 2 (5.6%) who gave birth in a car. This is different from the research done by.[3,8,15], which found that mothers who gave birth at home were ranked 85.3%, and those who gave birth in hospitals were 14.7%. This discrepancy can result from moms’ prior lack of knowledge about PPH.

Strength and Weakness: Nurses and the head of maternity care assisted and facilitated my study to achieve my objective. However, the sample size was insufficient, which may have an impact on how well the results generalize to other settings with large patient populations. However, hospital records were used to collect the specific outcome factors.

The following recommendations can be made based on the study’s findings: Through more community outreach by community health workers and Village health teams, the community needs to be educated more about safe and prompt delivery by skilled personnel for expectant mothers and those who are pregnant, generally women of childbearing age.[10] Health professionals should keep a watch on these moms during labor in accordance with the established risk factors to reduce the likelihood of PPH. Mothers are aware that regular ANC services are necessary for the early identification of various risk factors.

Government agencies should collaborate with hospitals to set accessible prices for women to pay for services provided to them during pregnancy and after delivery, so that they can access them when a problem arises. To treat severe PPH, the management protocol should be clearly defined, and blood transfusion services should be available. The requirement for knowledge on prenatal screening and the usage of trained labor attendants who adhere to safe delivery methods, such as controlled cord traction. Increase health worker hiring and pay to inspire them to work harder.[10] Patient variables. The importance of teaching mothers about family planning strategies should be emphasized by mother and child health clinics (MCH), since this gives the uterus time to reestablish its tonicity. To assess all risks and do blood grouping in case PPH occurs, mothers should be actively encouraged to have ANC checkups at least four times throughout pregnancy

Conclusion

PPH was common, occurring in 28% of the time, mainly in women with parities larger than or equal to four. In addition to forced labor and episiotomies, 56% of moms who arrived with PPH had delivered by Caesarean section, and 44% had given birth naturally. Additionally noteworthy characteristics include past PPH history and many pregnancies; this is comparable to the findings of. The main causes of PPH among women giving birth in ORSCH were hence induced labor and caesarean sections, multiple pregnancies and multiparity, as well as prior PPH history.

References

- Bangal V. Incidence, management, and outcome of atonic postpartum hemorrhage at a tertiary care hospital. Obstet Gynecol Res. 2018;1(2):45-50. doi:10.26502/ogr.4560008 Google Scholar

- Butwick AJ, Liu C, Guo N, et al. Association of gestational age with postpartum hemorrhage: An international cohort study. 2021;134(6):874-886. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000003730 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Fan D, Xia Q, Liu L, et al. The incidence of postpartum hemorrhage in pregnant women with placenta previa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0170194. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0170194 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Firmin M, Carles G, Mence B, et al. Postpartum hemorrhage: Incidence, risk factors, and causes in Western French Guiana. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2019;48(1):55-60. doi:10.1016/j.jogoh.2018.11.006

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Fukami T, Koga H, Goto M, et al. Incidence and risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage among transvaginal deliveries at a tertiary perinatal medical facility in Japan. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0208873. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208873 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kibira D. Access to sexual and reproductive health medicines and supplies in Sub-Saharan Africa. Utrecht University Library; 2021. Access to sexual and reproductive health medicines and supplies in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Kibira D, Ooms GI, van den Ham HA, et al. Access to oxytocin and misoprostol for management of postpartum hemorrhage in Kenya, Uganda, and Zambia: A cross-sectional assessment of availability, prices, and affordability. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e042948. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042948 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kinuthia K, Stephenson M, Maogoto E. Management of postpartum hemorrhage in a rural hospital in Kenya: A best practice implementation project. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep. 2019;17(2):248-258. doi:10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003826 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bell SF, Watkins A, John M, et al. Incidence of postpartum hemorrhage defined by quantitative blood loss measurement: A national cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1-9. doi:10.1186/s12884-020-02971-3 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- McLintock C. Prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage: Focus on hematological aspects of management. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2020;2020(1):542-546. doi:10.1182/hematology.2020000139 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Muthoni DM. Midwives preparedness in management of postpartum hemorrhage in Murang’a County, Kenya. Master’s thesis. Nairobi, Kenya: Kenyatta University; 2021. Accessed May 27, 2022. content

- Nyfløt LT, Sandven I, Stray-Pedersen B, et al. Risk factors for severe postpartum hemorrhage: A case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):e1217. doi:10.1186/s12884-016-1217-0 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ononge S, Mirembe F, Wandabwa J, Campbell OM. Incidence and risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage in Uganda. Reprod Health. 2016;13:38. doi:10.1186/s12978-016-0154-8 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- National Commission for Science, Technology & Innovation. Research information management system. 2024. NATIONAL GUIDELINES FOR REGISTRATION, LICENSING, AND REGULATION OF RESEARCHERS IN KENYA.pdf

- Ristanti A, Lutfiasari D, Pradian G, Pujiastuti SE. The correlation between parity and baby weight to the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage. The International Conference on Applied Science and Health. 2017:115-120. THE CORRELATION BETWEEN PARITY AND BABY WEIGHT TO THE INCIDENCE OF POSTPARTUM HEMORRHAGE | Semantic Scholar

- Walther D, Halfon P, Tanzer R, et al. Hospital discharge data is not accurate enough to monitor the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0246119. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246119. Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. 2019 Kenya population and housing census results. 2019. Accessed October 18, 2024. 2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census Reports – Kenya National Bureau of Statistics

Acknowledgments

I am sincerely grateful to the Department of Clinical Medicine at KMTC Nairobi for their essential support, patience, and valuable feedback. This project would not have been completed without the expertise of my supervisor. I am also indebted to my classmates, who helped me edit and proofread the document and offered insightful suggestions on several elements of the paper.

My thanks extend to the school library and to Mr. Patrick Macharia, the research assistant, who guided me through several sections of the work. I am deeply thankful to my family, particularly my brother, Dr. George Odhiambo Ochieng, and his wife, Dr. Emily Odondo, for their unwavering encouragement whenever I faced obstacles. I also wish to thank my spiritual mentor, Father Pharbian Ochieng, for his comfort and support throughout this journey. Finally, I am grateful to the editors at Medtigo, who reviewed and refined several parts of this paper.

Funding

Not reported

Author Information

Victor Okoth Ochieng

Department of Clinical Medicine and Surgery

Medical Training College, Nairobi, Kenya

Email: vochieng66@gmail.com

Author Contribution

The author contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles and was involved in the writing – original draft preparation and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

A formal request was submitted to the department of clinical medicine at KMTC headquarters in Nairobi to conduct this research project. The department head consented to the request and provided a formal introductory letter to ORSCH, soliciting the institution’s permission to participate in this research. Additionally, a permit license was acquired from NACOSTI, authorizing the research to be conducted.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Not reported

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Victor OO. Incidence of postpartum hemorrhage in patients attending Ongata Rongai Sub-Country Hospital in Kajiado County, Kenya. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622433. doi:10. 63096/medtigo30622433 Crossref