Author Affiliations

Abstract

Almost half (49%) of the United States population has prediabetes or type 2 diabetes. Type 2 diabetes is associated with numerous comorbidities, contributes substantially to morbidity and mortality, and is recognized as the seventh leading cause of death in the country. In addition, it remains the costliest chronic disease in the United States due to long-term complications and the ongoing need for medical care. Early detection of prediabetes creates opportunities for timely intervention, which can effectively prevent or delay the progression to type 2 diabetes. The objective of this quality improvement project was to develop and implement a screening algorithm in the primary care setting using the Prediabetes Risk Test and point-of-care Hemoglobin A1c testing to improve the identification of patients with prediabetes and increase referrals to lifestyle intervention. Over the 12-week implementation period, fifteen patients were identified as having prediabetes, three agreed to a referral to lifestyle intervention, and one was started on metformin. This was a marked increase compared to the two prior recent years. The algorithm was feasible and effective at improving the identification of prediabetes, in addition to improving staff, and providing knowledge and retention. Future studies should include a broader patient population in a variety of locations with longitudinal follow-up. Updating the Prediabetes Risk Test to specify physical activity for future studies may also be beneficial.

Keywords

Prediabetes, Type 2 diabetes, Screening algorithm, Prediabetes risk test, Point-of-care, HemoglobinA1c.

Introduction

More than 80% of the 96 million adults living with prediabetes in the United States (U.S.) are unaware of their condition.[1,2] Recent studies suggest that 26-50% of patients with prediabetes will progress to type 2 diabetes within five years if left unmanaged.[3-5] There is evidence to suggest that known complications of diabetes, such as retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy, increased risk of cardiovascular disease, and increased all-cause mortality, can be present in patients with prediabetes as well.[6,7] In addition, prediabetes and type 2 diabetes come with a significant financial toll. Type 2 diabetes is the most expensive chronic condition in the nation, with direct and indirect costs exceeding $327 billion per year.[8,9] Prediabetes further encumbers the healthcare system with an additional $43.4 billion annually.[9] As evident from the above, this prevalent disease increases the risk of negative health outcomes and places a significant burden on the healthcare system.

Prediabetes is an asymptomatic hyperglycemic state that increases the risk for cardiovascular disease, all-cause mortality, and developing overt type 2 diabetes.[6] Prediabetes and type 2 diabetes are global health concerns as the estimated prevalence of each is projected to rise around the world, mirroring rising rates of obesity and inactivity.[3,10] Risk factors for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes include being overweight or obese, family history of diabetes, history of gestational diabetes, limited physical activity, age > 45 years, smoking, and high blood pressure or cholesterol.[11] Intensive lifestyle-change programs have been successful at reducing the risk of progression to type 2 diabetes by 28-58% and long-term studies show reduced diabetes incidence after 10-15 years.[12,13] Treatment with the medication metformin can also reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes, though lifestyle intervention is almost twice as effective at reducing risk. While effective prevention strategies exist, providers must successfully screen and identify individuals with prediabetes to allow for early intervention to prevent or delay the progression to type 2 diabetes and its myriad complications.[14,15]

Definitions and screening guidelines for prediabetes vary by society and organization. The American diabetes association recommends screening begin at age 35 for all people, while the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening adults ages 35-70 who are overweight or obese, and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) recommends screening any adult who is overweight or obese.[16] Data show, however, 38-80% of those eligible for screening are not screened, only 5-25% are given a diagnosis when prediabetes is identified, and 0-23% are referred for behavior intervention when prediabetes is identified.[17-19] This evidence highlights numerous missed opportunities to identify and intervene early in this disease process.

To address this public health crisis, healthcare providers must improve their screening processes to ensure that those with prediabetes are identified in a timely manner, so that intervention with referral to lifestyle intervention can take place. This DNP project developed and implemented a screening algorithm that utilized a validated screening tool, point-of-care HbA1c testing, and referral recommendations to improve the identification of adults with prediabetes and increase referrals to lifestyle intervention.

Prediabetes definition and screening tests: Prediabetes is a frequently used term that encompasses several variations of hyperglycemia or elevated blood sugar, including impaired fasting blood glucose and impaired glucose tolerance.[20] The currently accepted screening tests for prediabetes include fasting blood glucose (FBG), oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and hemoglobinA1c (HbA1c). The ADA defines prediabetes as a HbA1c of 5.7%-6.4%, FBG of 100-125mg/dl, or OGTT of 140-199mg/dl at the 2-hour time point. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines prediabetes as a FBG of 110-125mg/dl, or an OGTT of 140-200mg/dl. The WHO endorses HbA1c for diabetes diagnosis; however, they do not for individuals with suspected prediabetes.[21-23]

Several factors need to be considered when choosing a screening test. FBG is inexpensive and provides quick results, but it is inconvenient because the individual is required to fast. Like the FBG, the OGTT requires fasting. It is a 2-hour test that requires ingestion of a sugary drink (75 grams of glucose) to reveal how an individual processes glucose. HbA1c testing, on the other hand, does not require fasting, has less pre-analytic instability, and less biological variability, though it is more expensive than FBG. Moreover, HbA1c provides a three-month average of blood glucose levels that can be useful to gauge over a longer time. Data suggest that while providers screen more frequently with FBG, often as part of a panel, screening with HbA1c is more likely to result in a diagnosis.[24] Although HbA1c could be considered the test of choice from a patient perspective, there are additional factors that need to be considered. Individuals with any alteration in red blood cell turnover, such as anemia, hemoglobinopathies, or pregnancy, may not have an accurate result. The use of point of care (POC) testing, done in the office with results in 1-10 minutes, for FBG and HbA1c has increased their availability and ease of use for screening. The ADA Standards of Care reports that all three tests are equally appropriate for diagnostic screening, though notes their concordance to be imperfect.[25,26]

Screening tools and risk tests: The first screening tool for diabetes was developed by the ADA in 1993, and since then, numerous tools have been developed to identify individuals at the highest risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Commonly used tools in the U.S. are the ADA screening tool and the CDC risk test. A 2014 systematic review of risk tests for prediabetes revealed gaps in validity and calibration: only seven of the 18 tools assessed were externally validated. A 2016 study of 9,391 adults, aged 20 years or older, directly comparing the ADA and CDC tools for the identification of prediabetes, found that the sensitivity (81%) and specificity (70.2%) of the ADA Prediabetes Risk test were superior to those of the CDC Prediabetes Screening Test.[27] In 2021, the CDC adopted the ADA risk test and is now known as the Prediabetes Risk Test, which is endorsed by both organizations and several others as well. Despite suboptimal sensitivity and specificity, the ADA’s Standards of Care still recommend either informal assessment of diabetes risk factors or the use of a screening tool, like the ADA risk test, to identify those in need of laboratory screening.[28,29]

Electronic health record tools: In addition to traditional questionnaire-based screening tests, EHR tools have been developed and successfully implemented to improve prediabetes screening. There is evidence to suggest that readily accessible EHR data (labs, body mass index (BMI), history) could be used to identify individuals who are high risk for or have prediabetes. A large quasi-experimental, mixed-methods study looked at how implementing a diabetes prevention toolkit affected the identification of Medicare patients with prediabetes and referral to diabetes prevention programs. The toolkit included an algorithm to query the EHR retrospectively to identify patients with prediabetes, based on HbA1c or FBG, and BMI >25 kg/m2. After implementation of the toolkit, the number of referrals to their local Diabetes Prevention Program increased from zero to 5,640 over a 15-month period.[30,31] A separate study looked at adapting the ADA risk score by eliminating physical activity and lowering the threshold for “high risk” from >5 to >4. Readily accessible EHR data were used, and individuals at high risk for prediabetes were easily identified.[32] These studies suggest that utilizing various EHR tools can have a significant positive impact on prediabetes identification and subsequent referrals.

Opportunistic or systematic screening: Another strategy to improve identification of prediabetes is opportunistic screening- employing POC testing with FBG or HbA1c at routine primary care visits–whether preventative, follow-up, or for other problems. This type of screening may reach more patients who may not otherwise seek preventative care. An example would be testing a patient presenting with a respiratory complaint, who also meets screening criteria, with POC HbA1c during the visit. A retrospective analysis of data collected over a two-year period at five primary care practices looked at screening outcomes in 4,421 private practice patients (group 1) and 7,464 community health center patients (group 2).[33] The study included patients who did not have a preexisting diagnosis of prediabetes or diabetes, were eligible for screening based on ADA and USPSTF guidelines, and had a point-of-care HbA1c test done at the time of the visit. While over 75% of patients were eligible for screening based on guidelines, only 21-23% were screened. Of those screened, 51% (group 1) and 63.1% (group 2) were identified as having prediabetes. This represented a substantial number of patients with prediabetes who otherwise might not have been identified. However, there was a significant number of patients eligible for screening who were not ultimately screened.[34]

Like opportunistic screening, a study comparing systematic screening with POC HbA1c and usual practice showed the former to be effective. In this prospective longitudinal study, 184 patients in the systematic screening arm were offered free POC HbA1c testing if they were over age 45 and did not have a diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes, while 324 patients in the standard care arm had “usual care,” which often included a blood glucose test as part of a standard laboratory panel for screening.. Systematically screening patients increased the chances for screening to occur, compared to standard practice (p = 0.005). Furthermore, there were 251 patients in the standard arms who were eligible for screening but were not screened. Systematic screening with POC HbA1c testing increased the likelihood of screening and afforded the opportunity for immediate education and management.[31]

Combination screening: Various screening strategies have proven beneficial in improving the identification of individuals with prediabetes, though no one strategy alone has been universally adopted or recommended. The use of more than one strategy, combination screening, could be more effective at achieving this goal. Guidelines recommend assessment of risk, whether informal or with a risk test, followed by laboratory testing for those who are identified as high risk. Shifting the laboratory testing to the point of care improves access to testing and enables immediate decision-making and intervention.[35]

A 2015 cross-sectional study of 3,386 patients evaluated the performance of a risk test (FINDIRSK) along with POC HbA1c testing to detect prediabetes or diabetes. Using both the risk test and POC HbA1c testing increased sensitivity to 84.2% for diabetes and 74.2% for prediabetes. Specificity also increased with this model, suggesting more accurate identification compared to either screening strategy alone.[28] Similar strategies, using a risk test and POC HbA1c testing, have been piloted in dental hygiene clinics and pharmacies and shown success at identifying patients with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes with referral back to primary care for management.[32-34]

Methodology

This DNP project developed a prediabetes screening algorithm based on ADA guidelines that included a validated screening tool, POC HbA1c testing, and referral recommendations, which was implemented in a primary care practice. The goals of this initiative were to improve the identification of adults with prediabetes and increase the number of referrals to lifestyle intervention programs. The project implementation site is a primary care practice in a suburban shoreline town that serves 5,636 patients. There is no practice- or organization-wide standard for prediabetes.

The prediabetes risk test was integrated with the screening algorithm into a two-sided form, the Prediabetes Screening Tool, that was used by staff and Providers. The MA verbally asked the Prediabetes Risk Test questions to all patients ages 18 and older without a diagnosis of prediabetes or diabetes, who presented for a routine physical exam with one of the four participating Providers during the rooming process by the MA. Those determined to be high risk (score of five or greater) had POC HbA1c testing completed. This test was done in the office, completing a fingerstick and using the Siemens DCA Vantage Analyzer machine, which meets the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program standards. These results were documented in the EHR and written on the back side of the Prediabetes Screening Tool and given to the provider.

Those who were identified as having prediabetes based on an HbA1c result of 5.7-6.4% were recommended to have a referral to lifestyle intervention, including Lifestyle Medicine, Weight Management, or Nutrition. If the HbA1c was 6.5% or greater, consistent with type 2 diabetes, the Provider ordered confirmatory testing and treated based on current ADA guidelines. The Project Lead retrieved the completed Prediabetes Screening Tools twice a week and entered the risk test answers, HbA1c (if applicable), and intervention: if and where a referral was made, or metformin started into REDCap.[33,34] The Prediabetes Screening Tools were then shredded. The algorithm, which outlines the above steps, can be found in Appendix D, Figure 4.

Education for staff and Providers on all the necessary topical areas to successfully implement the algorithm took place during a one-hour in-person education session delivered by the Project Lead that occurred prior to the start of implementation. A multiple-choice pre- and post-test was given to all attendees to assess learning. The test was re-administered at the end of implementation to assess retention of knowledge. Role plays using the algorithm took place to validate learning and involved each staff member and the Provider practicing their role.

Data analysis: Evaluation of the algorithm consisted of comparing data from the 12-week implementation period to those from the corresponding 12-week period one year prior and three years prior (September – December 2019 & 2021). This timeframe was chosen to eliminate seasonal variation. The year 2020 was excluded for comparison due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the lack of consistency in routine visits during that time. Data comprised the number of patients who were presented for routine physical exam, the number of patients identified as having prediabetes, and the number of patients with prediabetes referred to lifestyle intervention. The comparison data were obtained through EHR reports and included the number of patients who were presented for routine physical exam, the number of patients who received a new finding of prediabetes (or synonymous term including impaired fasting glucose, or impaired glucose tolerance), as well as the number of patients subsequently referred to lifestyle intervention.

Descriptive statistics were utilized to identify differences in prediabetes identification and lifestyle intervention referral before and after screening algorithm implementation. A one-way ANOVA using Tukey’s HSD (Honestly Significant Difference) was done to compare pre- and post-education tests and pre-education and post-implementation tests. Evaluation of provider and staff experience with the screening algorithm was done by an anonymous survey following implementation.

Prior to implementation, this project was presented to the Yale University IRB and was determined to be a quality improvement project. Additionally, the project site organization’s Nursing Research Council deemed this project a quality improvement. Ethical considerations included upholding patients’ rights to confidentiality, privacy, and safety. All patient participants were given an information sheet about taking part in a quality improvement project. Implementation took place from 9/26/2022 to 12/16/2022.

Results

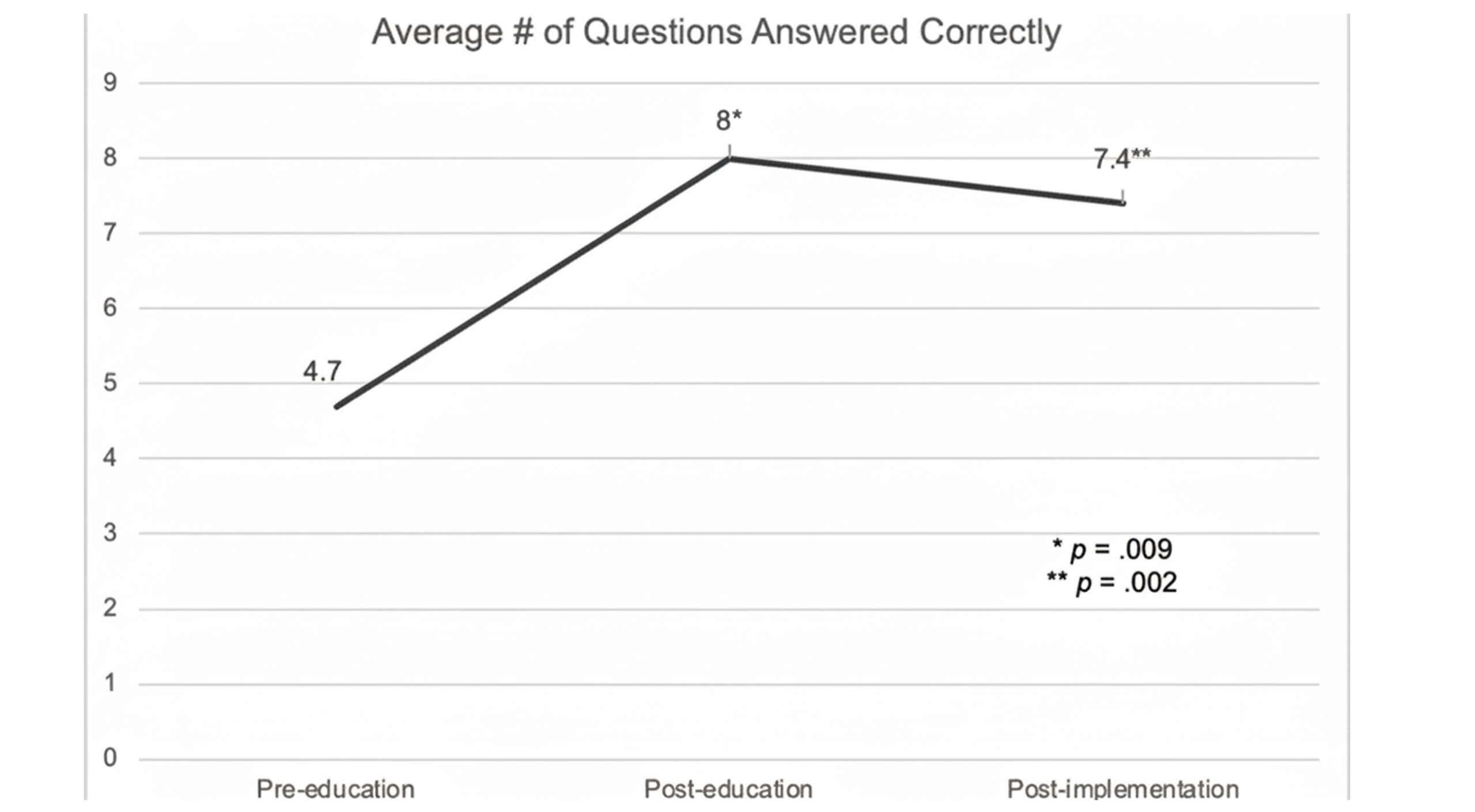

Staff education: Nine providers and staff members attended the education session. The anonymous pre- and post-test results showed an improved knowledge base following the education session (p = 0.009) and twelve weeks after the algorithm was implemented (p = 0.002 versus baseline); p = 0.76 versus post-education assessment (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Pre-post test results

Project participants: Over the 12-week implementation period, 413 patients were presented for routine physical exams. Of those, 316 patients completed the Prediabetes Screening Tool. Table 1 shows a comparison of the overall practice age and gender to those patients who were screened in the project and completed the prediabetes screening tool.

| Variable | Practice n (%) | Project n (%) | Project compared to practice |

| Age | |||

| Under 39 years | 1345 (24%) | 84 (27%) | +3% (p = NS) |

| 40-49 | 634 (11%) | 48 (15%) | +4% (p = NS) |

| 50-59 | 843 (15%) | 71 (22%) | +7% (p = 0.033) |

| 60 or older | 2814 (50%) | 113 (36%) | -14% (p <0.008) |

| Total | 5636 | 316 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 3019 (54%) | 170 (54%) | |

| Female | 2617 (46%) | 146 (46%) | |

| Total | 5636 | 316 | |

Table 1: Comparison of practice vs project age & gender

While the age distribution of the patients who were screened was less representative of the overall practice, the gender split mirrored that of the overall practice. Of those patients screened, three percent had a history of gestational diabetes, and 21% had a family history of a first-degree relative, other than offspring, with diabetes. Twenty-eight percent had a history of hypertension. Eighty-three percent of patients noted that they were physically active. Despite this, 67% of patients were considered overweight or obese based on BMI.

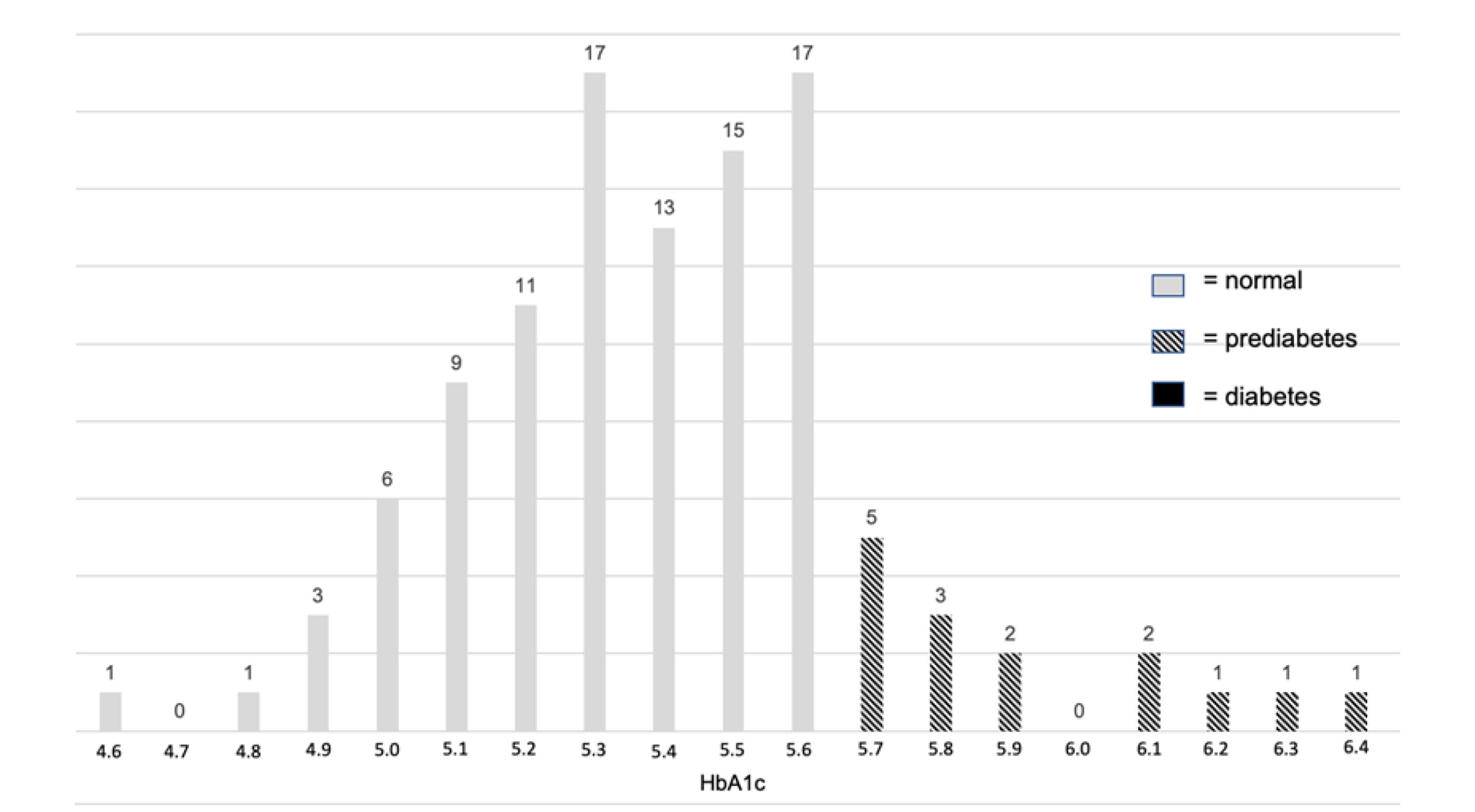

Prediabetes screening outcomes: One hundred and twelve patients (35%) of the 316 patients screened were identified as high risk. The most frequently recorded score was four, with 73 patients (23%) having this result. Three patients refused HbA1c testing. HbA1c results ranged from 4.6% to 12.9% (Figure 2). The mean HbA1c was 5.5% (SD +/- 0.78) and the median was 5.4%.

Figure 2: HemoglobinA1c results

Of those identified as high risk who completed POC HbA1c testing, 15 were identified as having prediabetes, which was 13% of those identified as high risk, and 4.7% of the total number of patients screened. One patient was identified as having type 2 diabetes. Four of the 15 patients identified (27%) agreed to an intervention. Three patients were referred to lifestyle medicine, and one was started on metformin. The remaining 11 patients (73%) declined intervention.

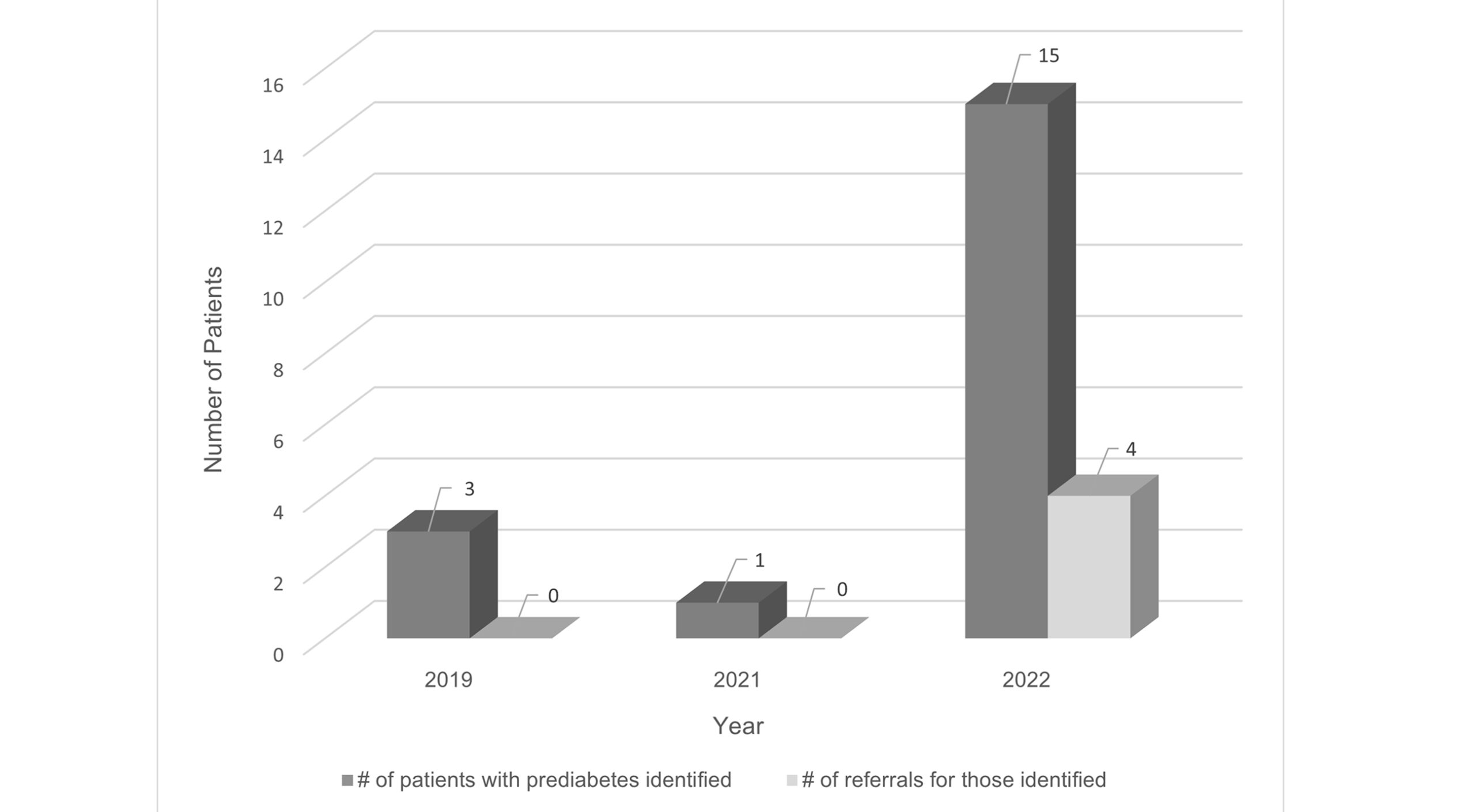

Comparison data: In 2019, 285 patients were presented for routine physical exam (four providers), and three patients were identified as having prediabetes. In 2021, 585 patients were presented for routine physical exams (five providers), and one patient with prediabetes was identified. No referrals were made for the patients who were identified as having prediabetes in 2019 and 2021. Utilizing the screening algorithm showed a marked increase in both the identification of prediabetes and referrals placed compared to the years analyzed prior to utilization of the algorithm (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Prediabetes identification and referrals

Post-implementation analysis: Following implementation, all staff and providers completed a 14-item survey for evaluation of the project. Using a five-point Likert scale, 100% of providers and staff strongly agreed that project communication was timely and informative, support was available when needed, the project was worthwhile, the overall assessment of the project was very good, and the project should be expanded to other primary care practices. The post-implementation survey also contained two open-ended questions to solicit recommendations for improvement and any additional comments or feedback. Two respondents recommended incorporating the paper Prediabetes Screening Tool into the electronic health record for patients to complete prior to their visit, while another recommended continuing the project as is. Several respondents wrote that the project was informative and beneficial to patients, and one specifically noted that the education sheet for patients was beneficial. Additional comments included that the screening algorithm was a fast and effective tool to identify prediabetes and improving insurance coverage for screening Medicare patients would be beneficial.

Discussion

Identifying prediabetes is essential to delaying type 2 diabetes, yet inconsistent reference ranges, limited screening, and low referral rates remain challenges. This project’s screening algorithm improved prediabetes identification and referrals compared with the previous two years. Staff and providers showed significant knowledge gains after training and retained this knowledge at 12 weeks, likely enhancing detection. Feedback was positive, and the Prediabetes Risk Test effectively guided additional screening. Its 13% positive predictive value aligns with the higher end of the range reported in the existing literature.[35-39]

There was a mismatch between routine physical exams (413) and completed Prediabetes Screening Tools (316). Contributing factors included excluding patients with known prediabetes or diabetes, failing to update appointment types in the EHR, and staff turnover that may have led to missed screenings. Patients aged 65 and older were underrepresented because Medicare does not cover routine physicals without supplemental insurance. Adults aged 50–59 were also unexpectedly underrepresented. One provider’s patients were excluded due to late arrival, and only 27% of identified patients accepted referrals.

Patients could have been overwhelmed with information, as this was the first time for many patients that prediabetes was mentioned or discussed. Additionally, many patients felt confident they could implement lifestyle modifications on their own. Some patients noted concern with the financial aspects of a referral, as co-pays are necessary for additional visits, with a higher cost associated with specialty visits.[40] To improve referral uptake, lifestyle medicine offered at the primary care site, or virtually through an application, might be more successful.[41] Future studies can look at re-screening patients in six months to one year to see if they would be more willing to accept a referral, if they still met criteria for prediabetes despite the lifestyle modifications they implemented or failed to implement despite their best intentions.

In this project, 83% of screened patients reported being physically active; however, the CDC notes that only 46.9% of adults meet the recommended guidelines of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity plus two days of muscle strengthening per week.[42] Because the Prediabetes Screening Tool does not quantify activity, patients with prediabetes may have been missed due to overly broad or inaccurate responses. This discrepancy is notable given that 23% of patients scored a 4 on the risk test. Future studies could improve accuracy by revising the question to: “Do you get 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity and two days of muscle strengthening weekly?” A clear yes/no format would maintain ease of use while improving identification of high-risk individuals.

Limitations: This project had several important limitations. Routine physical exam appointments were the focus because they emphasize screening and prevention, but Medicare does not cover routine physicals without supplemental insurance. As a result, many adults over age 65 who are at higher risk for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes were excluded. Future studies should apply the screening algorithm to follow-up visits to include Medicare patients without secondary coverage.

The sample population also limits generalizability. The project was conducted in a single center serving relatively financially advantaged communities, with limited socioeconomic and demographic diversity. Conducting similar projects in varied settings would improve understanding of prediabetes screening needs across populations.

Staffing shortages further affected implementation. Two trained medical assistants left mid-project, and rotating float staff received minimal training due to time constraints. A provider’s retirement and the onboarding of a new clinician also disrupted workflow. The short time frame prevented tracking whether referred patients attended lifestyle programs or assessing their readiness for change. Some patients preferred attempting lifestyle modifications independently. Long-term follow-up with referral attendance, HbA1c outcomes, and behavior-change assessment would strengthen future projects.

Strengths: This project demonstrated improved identification of prediabetes and increased referrals using a low-cost, feasible system suitable for primary care. The Prediabetes Screening Tool was easy for providers and staff to use, and integration into the EHR could further streamline workflows by allowing patients to complete risk questions before visits. A range of clinicians—MDs, a DO, and APRNs—used the tool and reported better knowledge of screening and management. The project also raised awareness of prediabetes among patients and staff. Providers reported greater confidence, more consistent screening, increased pre-visit lab ordering, and continued use of POC HbA1c testing for high-risk patients.

Practice implications: A major practice implication that emerged from this project is the need for consistent criteria and definition of prediabetes among organizations such as ADA, AACE, USPSTF, and WHO. Standardized screening guidelines would reduce confusion and varied practices among providers. Similarly, additional resources are needed, such as more diabetes prevention programs or lifestyle change programs that are readily accessible for those identified with prediabetes.

Conclusion

The screening algorithm utilized in this project, which included the Prediabetes Risk Test and POC HbA1c testing, was a feasible, low-cost, and effective way to improve prediabetes screening and identification in the primary care setting. Educating staff and providers about prediabetes and the project itself immediately prior to project implementation was effective and showed improved knowledge, based on pre- and post-test results, as well as retention of knowledge following implementation. While the project lacked a representative sample, future studies can be designed to incorporate more diverse populations. Additionally, there remains a gap in the uptake of referrals that must be addressed. The results of this project support the utilization of combination screening, with a validated risk test and POC HbA1c testing, at outpatient preventative care visits to improve prediabetes identification and increase referrals to lifestyle intervention.

References

- CDC. Adult Obesity Facts. 2024.

Adult Obesity Facts - CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report. 2024.

National Diabetes Statistics Report - Duan D, Kengne AP, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB. Screening for Diabetes and Prediabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2021;50(3):369-385. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2021.05.002

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Selvin E. Prediabetes and What It Means: The Epidemiological Evidence. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;42:59-77. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102644

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas 2025. 2025.

IDF Diabetes Atlas 2025 - Richter B, Hemmingsen B, Metzendorf MI, Takwoingi Y. Development of type 2 diabetes mellitus in people with intermediate hyperglycaemia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10(10):CD012661. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012661.pub2

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Cai X, Zhang Y, Li M, et al. Association between prediabetes and risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease: updated meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m2297. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2297

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - CDC. Health and Economic Benefits of Diabetes Interventions. 2024.

Health and Economic Benefits of Diabetes Interventions - CDC. Cost-effectiveness of interventions to prevent and control diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. 2010.

Cost-effectiveness of interventions to prevent and control diabetes mellitus: a systematic review - Dall TM, Yang W, Gillespie K, et al. The Economic Burden of Elevated Blood Glucose Levels in 2017: Diagnosed and Undiagnosed Diabetes, Gestational Diabetes Mellitus, and Prediabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(9):1661-1668. doi:10.2337/dc18-1226

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - CDC. Diabetes Risk Factors. 2024.

Diabetes Risk Factors - Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term effects of lifestyle intervention or metformin on diabetes development and microvascular complications over 15-year follow-up: the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(11):866-875. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00291-0

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP). 2021.

Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) - Albright AL, Gregg EW. Preventing type 2 diabetes in communities across the U.S.: the National Diabetes Prevention Program. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(4 Suppl 4):S346-351. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.009

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(Suppl 1):S19-40. doi:10.2337/dc23-S002

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - International Expert Committee. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(7):1327-1334. doi:10.2337/dc09-9033

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Barry E, Roberts S, Oke J, Vijayaraghavan S, Normansell R, Greenhalgh T. Efficacy and effectiveness of screen and treat policies in prevention of type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of screening tests and interventions. BMJ. 2017;356:i6538. doi:10.1136/bmj.i6538

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Blonde L, Umpierrez GE, Reddy SS, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline: Developing a Diabetes Mellitus Comprehensive Care Plan-2022 Update. Endocr Pract. 2022;28(10):923-1049. doi:10.1016/j.eprac.2022.08.002

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Brunisholz KD, Conroy MB, Belnap T, Joy EA, Srivastava R. Measuring Adherence to U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Diabetes Prevention Guidelines Within Two Healthcare Systems. J Healthc Qual. 2021;43(2):119-125. doi:10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000281

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Evron JM, Herman WH, McEwen LN. Changes in Screening Practices for Prediabetes and Diabetes Since the Recommendation for Hemoglobin A1c Testing. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(4):576-584. doi:10.2337/dc17-1726

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Mainous AG III, Tanner RJ, Baker R. Prediabetes diagnosis and treatment in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(2):283-285. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2016.02.150252

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Mainous AG 3rd, Rooks BJ, Wright RU, Sumfest JM, Carek PJ. Diabetes Prevention in a U.S. Healthcare System: A Portrait of Missed Opportunities. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62(1):50-56. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2021.06.018

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Nhim K, Khan T, Gruss SM, et al. Primary Care Providers’ Prediabetes Screening, Testing, and Referral Behaviors. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(2):e39-e47. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.017

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Obinwa U, Pérez A, Lingvay I, Meneghini L, Halm EA, Bowen ME. Multilevel Variation in Diabetes Screening Within an Integrated Health System. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(5):1016-1024. doi:10.2337/dc19-1622

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Thomas TW, Golin CE, Kinlaw AC, et al. Did the 2015 USPSTF Abnormal Blood Glucose Recommendations Change Clinician Attitudes or Behaviors? A Mixed-Method Assessment. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(1):15-22. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-06749-x

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Barber SR, Davies MJ, Khunti K, Gray LJ. Risk assessment tools for detecting those with pre-diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;105(1):1-13. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2014.03.007

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Gamston CE, Kirby AN, Hansen RA, et al. Comparison of 3 risk factor-based screening tools for the identification of prediabetes. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2020;60(3):481-484. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2019.11.015

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Poltavskiy E, Kim DJ, Bang H. Comparison of screening scores for diabetes and prediabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2016;118:146-153. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2016.06.022

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Zhang Y, Hu G, Zhang L, Mayo R, Chen L. A novel testing model for opportunistic screening of pre-diabetes and diabetes among U.S. adults. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0120382. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0120382

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Holliday CS, Williams J, Salcedo V, Kandula NR. Clinical Identification and Referral of Adults With Prediabetes to a Diabetes Prevention Program. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16:E82. doi:10.5888/pcd16.180540

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Chima CC, Anikpezie N, Pongetti LS, Wade BC, Powell T, Beech B. 1443-P: Can the ADA Diabetes Risk Score Be Approximated Using Routine Data in the Electronic Health Record? Findings from a Federally Qualified Health Center. Diabetes. 2020;69(Suppl 1):1443-P. doi:10.2337/db20-1443-P

Crossref | Google Scholar - Whitley HP, Hanson C, Parton JM. Systematic Diabetes Screening Using Point-of-Care HbA1c Testing Facilitates Identification of Prediabetes. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(2):162-164. doi:10.1370/afm.2035

PubMed| Crossref | Google Scholar - Giblin LJ, Rainchuso L, Rothman A. Utilizing a Diabetes Risk Test and A1c Point-of-Care Instrument to Identify Increased Risk for Diabetes in an Educational Dental Hygiene Setting. J Dent Hyg. 2016;90(3):197-202.

Utilizing a Diabetes Risk Test and A1c Point-of-Care Instrument to Identify Increased Risk for Diab… - Genco RJ, Schifferle RE, Dunford RG, Falkner KL, Hsu WC, Balukjian J. Screening for diabetes mellitus in dental practices: a field trial. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(1):57-64. doi:10.14219/jada.2013.7

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Ward ED, Hopkins WA, Shealy K. Evaluation of the Use of a Diabetes Risk Test to Identify Prediabetes in an Employee Wellness Screening. J Pharm Pract. 2022;35(4):524-527. doi:10.1177/0897190021997010

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Bang H, Edwards AM, Bomback AS, et al. Development and validation of a patient self-assessment score for diabetes risk. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(11):775-783. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00005

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Heikes KE, Eddy DM, Arondekar B, Schlessinger L. Diabetes Risk Calculator: a simple tool for detecting undiagnosed diabetes and pre-diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(5):1040-1045. doi:10.2337/dc07-1150

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Herman WH, Smith PJ, Thompson TJ, Engelgau MM, Aubert RE. A new and simple questionnaire to identify people at increased risk for undiagnosed diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18(3):382-387. doi:10.2337/diacare.18.3.382

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Ali MK, Echouffo-Tcheugui J, Williamson DF. How effective were lifestyle interventions in real-world settings that were modeled on the Diabetes Prevention Program?. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(1):67-75. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1009

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - CDC. Adult Activity: An Overview. 2023.

Adult Activity: An Overview - Sobolesky PM, Smith BE, Saenger AK, et al. Multicenter assessment of a hemoglobin A1c point-of-care device for diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Clin Biochem. 2018;61:18-22. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.09.007

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

None

Funding

None

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Katherine Masoud

Department of Internal Medicine

Hartford Healthcare Medical Group, USA

Email: katherinemasoud@gmail.com

Co-Author:

Neesha Ramchandani

Yale University School of Nursing, USA

Authors Contributions

Katherine Masoud contributed to the conception and design of the study, collected and analyzed the data, and led the writing of the manuscript. Neesha Ramchandani supervised the project, contributed to data analysis, and critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Yale University IRB determined this to be a quality improvement project. The project site organization’s Nursing Research Council deemed this project a quality improvement. Ethical considerations included upholding patients’ rights to confidentiality, privacy, and safety. All patient participants were given an information sheet about taking part in a quality improvement project.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Masoud K, Ramchandani N. Implementing a Prediabetes Screening Algorithm to Improve Identification and Referrals in Primary Care. medtigo J Med. 2025;3(4):e3062347. doi:10.63096/medtigo3062347 Crossref