Author Affiliations

Abstract

Background: Hypertriglyceridemia (HTG) is the third leading cause of acute pancreatitis, responsible for up to 10% of cases. HTG pancreatitis is often more severe and complicated, with clinical presentation and diagnosis like other forms of acute pancreatitis. Management involves treating acute pancreatitis and reducing serum triglyceride (TG) levels below 500 mg/dl to prevent necrotizing pancreatitis. While plasmapheresis and other rapid reduction techniques exist, they are costly and less accessible in Africa. Insulin infusion, alone or with heparin, has shown potential in case studies for lowering TG, yet evidence is limited, with only one publication on their combined use. No studies have been published in Africa on using insulin alone for HTGP treatment.

Case report: We report a case of a 30-year-old Ethiopian male smoker and alcoholic, who presented to the emergency department with severe epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting for one day. He was tachycardic, obese, and had a tender, distended abdomen. Laboratory tests revealed a serum TG level of 2205 mg/dL. An abdominal CT scan showed diffuse pancreatic swelling and minimal peripancreatic fluid. Diagnosed with HTG pancreatitis, he was treated with intravenous insulin alone, and he was discharged without complications.

Conclusion: Our findings, based on case-control trials and case reports, support the safety and efficacy of insulin therapy for HTG pancreatitis. In resource-limited countries like Africa, insulin is more accessible than treatments like plasmapheresis, helping to prevent complications. This report aims to enhance physicians’ understanding of insulin management and encourage further research in this area.

Keywords

Pancreatitis, Hypertriglyceridemia, Insulin, Dextrose water, Plasmapheresis.

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis is an inflammatory disorder of the pancreas, often characterized by abdominal pain and elevated pancreatic enzyme levels in the blood.[1] A range of factors can initiate this condition, although the level of certainty regarding these triggers can differ. However, the precise mechanisms behind this illness are still not fully understood.[2] The global incidence of acute pancreatitis has been estimated to be 33.74 per 100,000 population, while its mortality has been estimated to be 1.16 per 100000 population.[3] The two most frequent causes of acute pancreatitis are alcohol and gallstones.[4] HTG is the third leading cause of acute pancreatitis, accounting for 4% to 10% of all acute pancreatitis cases globally in recent years and up to 56% of acute pancreatitis cases during pregnancy.[5,6] Although the precise mechanism by which HTG causes acute pancreatitis is not fully understood, both HTG, by causing an excess of free fatty acids (FFAs) and elevated chylomicrons, are thought to increase plasma viscosity, which may induce ischemia in pancreatic tissue and trigger organ inflammation.[7-9] The risk of developing acute pancreatitis is approximately 5 percent with serum TG >1000 mg/dL (11.3 mmol/L) and 10 to 20 percent with TG >2000 mg/dL (22.6 mmol/L).[10] The etiology of HTGP is divided into two categories: primary (genetic) and secondary disorders of lipoprotein metabolism.[10,11] Types I (high chylomicrons), very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), and high chylomicrons dyslipidemias are associated with severe HTG and an increased risk of acute pancreatitis.[12] Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus (DM) (types 1 and 2), diabetic ketoacidosis can trigger HTGP.[13]

The initial symptoms of hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis (HTGP) closely resemble those of acute pancreatitis from other causes, presenting intense abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. However, individuals with pancreatitis due to high TG levels often experience more severe disease progression and have a greater risk of ongoing organ failure. During a physical exam, signs of HTG may be evident, such as eruptive xanthomas on extensor surfaces resulting from prolonged hyperchylomicronemia or hepatosplenomegaly. Additionally, lipemia retinalis is a rare complication that can occur when TG levels exceed 4000 mg/dL.[11] The diagnosis for acute pancreatitis from other causes is identical and necessitates meeting two out of the following three criteria: sudden onset of pain consistent with acute pancreatitis usually in the epigastric region, often radiating to the back, an elevation in serum lipase or amylase levels exceeding three times the upper limit of normal, and distinctive acute pancreatitis findings on imaging.[14,15] Treatment guidelines for HTGP are not standardized, and current approaches involve providing standard supportive therapy for acute pancreatitis, such as stopping enteral intake, replenishing fluids, and providing opiate analgesia, quickly reducing plasma TG levels, and lowering the chances of pancreatitis recurring by removing its triggering factors.[15] Plasmapheresis, insulin infusion, heparin, fibrates therapy, and apolipoprotein C-II (apoC-II) derivatives have been utilized to achieve these objectives.[16,17]

The cost of plasmapheresis is high, it is not easily available, and there is not strong evidence supporting its effectiveness in reducing illness and death, despite its ability to lower serum TG levels to the desired level within 3 hours. Fibrate therapy is only used for the long-term treatment of HTG, and apolipoprotein C-II derivatives are hard to obtain and are not widely used.[17] Insulin alone or in combination with heparin, despite being affordable and readily available, has not been conclusively proven to be effective in treating HTGP.[3] Heparin and insulin stimulate lipoprotein lipase (LPL), leading to a decrease in plasma TG levels. Insulin is administered as an infusion in all instances, while heparin is given either subcutaneously (SC) or intravenously (IV) at different dosages. Literature has utilized both unfractionated and low molecular-weight heparin, and both types appear to be equally effective.[15-17]

Although no concrete guidelines exist as to the treatment of HTGP, it has been demonstrated in different case reports that insulin infusion is effective in lowering TG.[18] It is proposed that insulin increases LPL activity, which degrades chylomicrons, thus reducing serum TG.[19] However, the role of heparin remains controversial as it has been shown to transiently increase endothelial release of LPL, but in the long term, may lead to heparin degradation, resulting in an actual overall depletion of LPL.[18,20] It has been shown in various case series and randomized controlled trials that a combination infusion therapy of heparin and insulin can be safely used to treat pancreatitis induced by HTG. However, only one publication has addressed the use of insulin and heparin to treat HTGP in the African continent, where other treatment options are either costly or unavailable. This report aims to specifically demonstrate that an affordable, efficient, and safe therapy for HTGP is accessible and can be utilized in Africa.

Case Presentation

A 30-year-old smoker and alcoholic male Ethiopian, with no previous known medical illness, presented to the emergency department with a complaint of a sudden onset of severe epigastric abdominal pain which radiated to the back, nausea, and vomiting of 1 day duration. He claims that he has a history of fatty meals. He had been complaining of excessive thirst, urination, and fatigue 1 week prior to presentation. Has a family history of diabetes and obesity.

Upon examination, he is acutely sick looking in pain and with central obesity on general appearance, his blood pressure (BP) was 140/80 mmHg, a pulse rate of 108 beats per minute, a temperature of 36.3℃, a respiratory rate of 24 breath per minute, oxygen saturation on 90% on atmospheric air, and a body mass index (BMI) of 35 kg/m2. He had bilateral posterior basal third crepitation and decreased air entry, suggestive of reactive effusion. The abdomen was distended, and there was a hypertympanic note on the percussion, with tenderness over the epigastric and right lower quadrant area. There was no eruptive xanthoma.

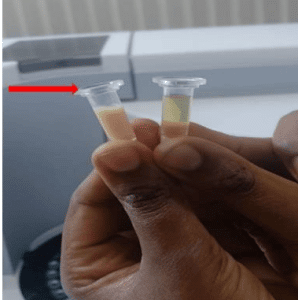

His blood test result on the day of admission was not reported completely as it was highly lipemic (Figure 1). Complete blood count (CBC) showed that he had a leukocytosis of 14,700 cells/mm3, hemoglobin of 23 g/dL, and a platelet count of 204 000 cells/mm3. His random sugar level and Hgb A1c level were 504 g/dL and 13.5%, respectively, and his urine ketone level was +3. He had a serum TG level of 2205 mg/dL, a serum cholesterol level of 492 mg/dL, and a low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level of 159 mg/dL. His serum lipase level was 127, and serum potassium was 2.7 mEq/L. Renal function test, creatinine was 1.48 mg/dL, transaminase levels, and electrolytes were in the normal range on admission.

| Laboratory parameters | On admission | 48 hours | 5th day |

| White cell count (Cells/mm3) | 14,500 | 10,500 | 9,500 |

| Hgb (g/dL) | 23 | 17.1 | 15.4 |

| Platelet (Cells/mm3) | 204,000 | 157,000 | 125,000 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 2205 | 1166 | 327 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 492 | ||

| LDL (mg/dL) | 156 | ||

| Lipase (U/L) | 127 | 88 | 54 |

| Amylase (U/L) | 104 | 26 | |

| Random blood sugar (mg/dL) | 504 | 216 | 126 |

| Urine ketone | +3 | +2 | -ve |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 136 | 136 | |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | 2.75 | 2.81 | |

| Serum calcium (mEq/L) | 0.89 | 1.20 | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.48 | 0.58 | 0.40 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (mg/dL) | 25 | 30 | 22 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (U/L) | 26 | 52 | 22 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (U/L) | 22 | 28 | 30 |

| Hgb A1c (%) | 13.5% | ||

| C-reactive protein (CRP) (mg/L) | 13.5 | 30.5 | 23.2 |

Table 1: Abnormal laboratory parameters

Case Management

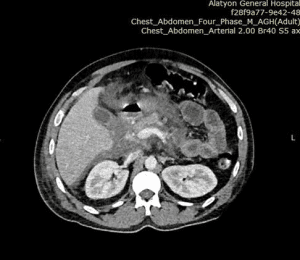

Before admission, he was initially imaged with abdominal ultrasound, and the visualization and detailed assessment of the pancreas was difficult because of a gaseous stomach. For this abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast, it shows that there is an enlarged pancreas head, neck, and uncinate process with heterogenous enhancement, stranding peripancreatic tissue with minimal peripancreatic fluid collection (Figure 2). We were not able to perform genetic tests for hyperlipidemia, due to the lack of access to the investigation and financial reasons.

Figure 1: Lactescent serum sample of our patient (red arrow) compared with normal serum

Figure 2: Diffusely edematous pancreas with minimal peripancreatic fluid collection (white arrow)

He was admitted with a diagnosis of severe HTGP and newly diagnosed type II DM with diabetic ketoacidosis, and for this, he was given 5 bags of IV normal saline with 40 mEq/L potassium chloride (KCL) added to each bag, a standing dose of morphine, and he was kept NPO. Insulin IV was given as loading dose on 0.1U/kg, which is 10 International Unit (IU) IV and 10 IU intramuscular (IM) with following dose of 5 IU IV every hour until his serum TG <500 mg/dL, he was put on 5% dextrose in water (DW) to prevent hypoglycemia, but he hadn’t any. He has been followed by blood sugar level every hour, urine ketone every 4 hours, and serum TG level every 24 hours. He was taken out of diabetic ketoacidosis within 48 hours, and the serum TG level dropped to a normal value within 4 days of his treatment. He was discharged 10 days after admission, with fenofibrate 45 mg orally (po) daily, metformin 500 mg po two times daily (bid), tramadol 50 mg po as required (prn), and advised on lifestyle modification.

After being discharged, he made two follow-up visits. He was taking his medicine as prescribed, and on following physical examination, his chest was clear, his belly showed no evidence of discomfort, and he had no history of nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain. His follow-up abdominal CT scan reveals a significant radiologic improvement from the prior imaging, and his laboratory studies revealed that he had good glycemic control and a serum TG level of 200 mg/dL.

Discussion

| Publications | Patients no | Serum TG (mg/dL) | Insulin | Heparin | ||

| Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 5 | ||||

| Kuchay MS et al.[15] | 4 | 1820-5860 | 876-2289 | 221-504 | Infusion | UFH SC |

| Alagözlü H et al.[16] | 1 | 3587 | —— | 673 | Infusion | Not administer |

| Jain P et al.[17] | 1 | 1276 | —– | 193 | Infusion | Not administer |

| Patel et al.[18] | 1 | 5000 | 923 | 423 | Infusion | UFH IV |

| Our patient | 1 | 2205 | 1166 | 327 | Every 1hr | Not administer |

Table 2: Comparison of insulin heparin regimen and our patient’s TG level to previous studies

Management of HTGP includes supportive management (fluid and electrolyte management, pain control, bowel rest) and specific treatment directed to lowering plasma TG level to less than 500 mg/dl. SC and IV heparin and insulin infusion were used in case reports to lower plasma TG and target levels, which improved outcomes. Using heparin has a risk of hemorrhagic pancreatitis in severe HTGP. Safety of insulin alone treatment for HTGP remains elusive and needs to be tested. In this case report, the patient was safely treated with hourly insulin alone to lower plasma TG to <500 mg/dL in 5 days.

Conclusion

HTGP is a less common but sever type of pancreatitis and should be considered in obese individuals presenting with acute pancreatitis with high TG levels. In resource-limited countries, satisfactory clinical outcomes could be achieved by using insulin alone as a continuous infusion or hourly intravenous administration.

References

- Cecil RL, Goldman L, Schafer AI. Goldman’s Cecil Medicine. 24th ed. eBook. W.B. Saunders; 2012. Goldman’s Cecil Medicine

- Eugenia L, María R-P, Luis Rodrigo S. Etiology of Pancreatitis and Risk Factors. In: Luis R, ed. Acute and Chronic Pancreatitis. Intech Open. 2015. doi:10.5772/58941 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Anbessie ZM, Gebremeskel YB. Hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis managed with heparin and insulin: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2023;17(1):256. doi:10.1186/s13256-023-03995-x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Samanta J, Dhaka N, Gupta P, et al. Comparative study of the outcome between alcohol and gallstone pancreatitis in a high-volume tertiary care center. JGH Open. 2019;3(4):338-343. doi:10.1002/jgh3.12169 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gayam V, Mandal AK, Gill A, et al. A rare case of acute pancreatitis due to very severe hypertriglyceridemia (>10,000 mg/dL) successfully resolved with insulin therapy alone: a case report and literature review. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2018;6:232470961879839. doi:10.1177/2324709618798399 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gao L, Li W. Hypertriglyceridemia and acute pancreatitis: clinical and basic research a narrative review. J Pancreatol. 2024;7(1):53-60. doi:10.1097/JP9.0000000000000153 Crossref | Google Scholar

- de Pretis N, Amodio A, Frulloni L. Hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: Epidemiology, pathophysiology and clinical management. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(5):649-655. doi:10.1177/2050640618755002 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ewald N, Hardt PD, Kloer HU. Severe hypertriglyceridemia and pancreatitis: presentation and management. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2009;20(6):497-504. doi:10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283319a1d PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Valdivielso P, Ramírez-Bueno A, Ewald N. Current knowledge of hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(8):689-694. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2014.08.008 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lloret Linares C, Pelletier AL, Czernichow S, et al. Acute pancreatitis in a cohort of 129 patients referred for severe hypertriglyceridemia. Pancreas. 2008;37(1):13-22. doi:10.1097/MPA.0b013e31816074a1 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Yang AL, McNabb-Baltar J. Hypertriglyceridemia and acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2020;20(5):795-800. doi:10.1016/j.pan.2020.06.005 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Scherer J, Singh VP, Pitchumoni CS, Yadav D. Issues in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: an update. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(3):195-203. doi:10.1097/01.mcg.0000436438.60145.5a PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Fortson MR, Freedman SN, Webster PD 3rd. Clinical assessment of hyperlipidemic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(12):2134-2139. Clinical assessment of hyperlipidemic pancreatitis

- Fredrickson DS. An international classification of hyperlipidemias and hyperlipoproteinemias. Ann Intern Med. 1971;75(3):471-472. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-75-3-471 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kuchay MS, Farooqui KJ, Bano T, Khandelwal M, Gill H, Mithal A. Heparin and insulin in the management of hypertriglyceridemia-associated pancreatitis: case series and literature review. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2017;61(2):198-201. doi:10.1590/2359-3997000000244 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Alagözlü H, Cindoruk M, Karakan T, Unal S. Heparin and insulin in the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia-induced severe acute pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51(5):931-933. doi:10.1007/s10620-005-9006-z PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Jain P, Rai RR, Udawat H, Nijhawan S, Mathur A. Insulin and heparin in treatment of hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(18):2642-2643. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i18.2642 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Patel AD. Hypertriglyceridemia-induced acute pancreatitis treatment with insulin and heparin. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(4):671-672. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.98050 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Coskun A, Erkan N, Yakan S, et al. Treatment of hypertriglyceridemia-induced acute pancreatitis with insulin. Prz Gastroenterol. 2015;10(1):18-22. doi:10.5114/pg.2014.45412 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Näsström B, Olivecrona G, Olivecrona T, Stegmayr BG. Lipoprotein lipase during continuous heparin infusion: tissue stores become partially depleted. J Lab Clin Med. 2001;138(3):206-213. doi:10.1067/mlc.2001.117666 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the patient for providing consent to share his history as a case report and Alatyon General Hospital for evaluating the case and providing ethical clearance.

Funding

No specific grant was obtained for this case report from any funding agency.

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Mamaru Sintayehu Ayenew

Department of Internal Medicine

Alatyon General Hospital, Ethiopia

Email: mamarusintie@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Yonas Kassahun Habtegiorgies, Leykun Demeke Seifu, Biruk Belachew Bedore

Department of Internal Medicine

Alatyon General Hospital, Ethiopia

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Informed Consent

Ethical approval was obtained from Alatyon General Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Not reported

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Mamaru SA, Yonas KH, Leykun DS, Biruk BB. Hypertriglyceridemia-Induced Acute Pancreatitis: Management with only Insulin. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622448. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622448 Crossref