Author Affiliations

Abstract

Syncope is a transient loss of consciousness with a broad differential diagnosis, among which cardiac etiologies are particularly concerning due to their association with increased morbidity and mortality and their frequent lack of prodromal symptoms. Hyperthyroidism is well recognized for its cardiovascular effects, most commonly causing sinus tachycardia and supraventricular arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation. Ventricular arrhythmias, however, are rare and infrequently reported as a presenting manifestation of thyrotoxicosis. We report the case of a 63-year-old woman who presented with sudden syncope without warning signs, raising concern for cardiac syncope. Initial electrocardiography revealed frequent premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), including interpolated PVCs mimicking ventricular bigeminy, supporting a presumed cardiogenic etiology. The patient was admitted for further cardiac evaluation. Comprehensive diagnostic workup ultimately revealed severe thyrotoxicosis, with markedly elevated free triiodothyronine and thyroxine levels, suppressed thyroid-stimulating hormone, and positive thyroid receptor antibodies, consistent with Graves’ disease. The ventricular ectopy and syncopal episode were attributed to untreated hyperthyroidism. Initiation of antithyroid therapy resulted in clinical stabilization, and no malignant arrhythmias were identified on subsequent monitoring. This case underscores the importance of considering thyroid dysfunction in patients presenting with syncope and ventricular ectopy, even when electrocardiographic findings suggest a primary cardiac cause. Early recognition and treatment of thyrotoxicosis are essential to prevent potentially life-threatening arrhythmias and other cardiovascular complications.

Keywords

Hyperthyroidism, Thyrotoxicosis, Premature ventricular contractions, Cardiac syncope, arrhythmia, Ventricular ectopy.

Introduction

Sinus tachycardia is the most prevalent rhythm disturbance associated with hyperthyroidism. However, there is also a notably increased incidence of atrial fibrillation, atrial arrhythmias, and congestive heart failure in these patients. While ventricular arrhythmias are relatively rare, they can occur under specific circumstances.[1,2] Rare cases of ventricular arrhythmias, such as premature ventricular contractions with bigeminy as a primary presentation of hyperthyroidism, have not been reported in the literature.

In the emergency room, the patient’s history, along with 12-lead EKG findings, helps determine whether syncope has a cardiac origin.[3] In EKG readings, PVCs happen when the heartbeat originates from the ventricles.[4] While the exact reasons for PVCs remain unclear, potential mechanisms include triggered activity, automaticity, and reentry.[5] They can occur in groupings, and when they do, they are referred to as ventricular ectopy, which can be bigeminy, trigeminy, couplets, or triplets.[4] Bigeminy occurs when ventricular ectopics appear every second beat. Ventricular ectopy in a healthy heart is typically infrequent; however, in patients requiring Holter monitoring, it can be common, especially in older age ranges. While generally thought to be harmless, they can be a precursor to tachyarrhythmias in patients with heart disease.[4] Elevated PVC frequency could potentially serve as a risk factor for heart failure and mortality.[5] Interpolated PVCs occur when there are no compensatory pauses, and the sinus rhythm is not affected by the ectopic beat.[4] However, comprehensive associations between these patterns remain challenging to identify in the literature.

Thyroid hormones affect the heart and can increase the risk of developing heart failure and/or life-threatening arrhythmias.[6-10] Thus, the impact of thyroid hormones on cardiac health is substantial and warrants careful consideration. Thyrotoxicosis is characterized by the sustained elevation of free triiodothyronine (T3) and free thyroxine (T4), or both. This condition can commonly arise from causes such as Graves’ disease and toxic multinodular goiter, in addition to inflammation secondary to certain medications, notably amiodarone and iodine.[7] In the case presented, the initial clinical evidence suggested cardiac syncope, as indicated by EKG findings of interpolated PVCs that were initially misinterpreted as ventricular bigeminy, coupled with the absence of prodromal symptoms. However, further evaluation revealed that hyperthyroidism with thyrotoxicosis was the likely underlying cause of the syncope. This case highlights the critical importance of evaluating thyroid dysfunction in patients presenting with cardiac arrhythmias, including PVCs exhibiting bigeminy.

Case Presentation & Management

A 63-year-old female presented to the emergency department after an episode of syncope. She had been at work when the episode occurred. Notably, she was sitting, taking a break, when she collapsed onto the ground. There were no precipitating factors or warning signs that a syncopal episode might occur. She had never experienced an episode like this before. She has a personal medical history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which was thought to be in remission at the time, along with asthma (also in remission) and hypertension. Her medications at home included fluticasone propionate 110 mcg inhaler daily, albuterol sulfate 90 mcg inhaler 1-2 puffs every 6 hours as needed, hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg tablet once daily, lisinopril 40 mg tablet once daily, and atorvastatin 40 mg tablet once at night. Recently, she had noted worsening shortness of breath on exertion and difficulty completing one flight of stairs. Additionally, she had short breaths when lying, requiring pillows to sleep. She endorsed dizziness that had been ongoing without workups. She previously had a heart catheterization the month prior, which showed post-capillary pulmonary hypertension.

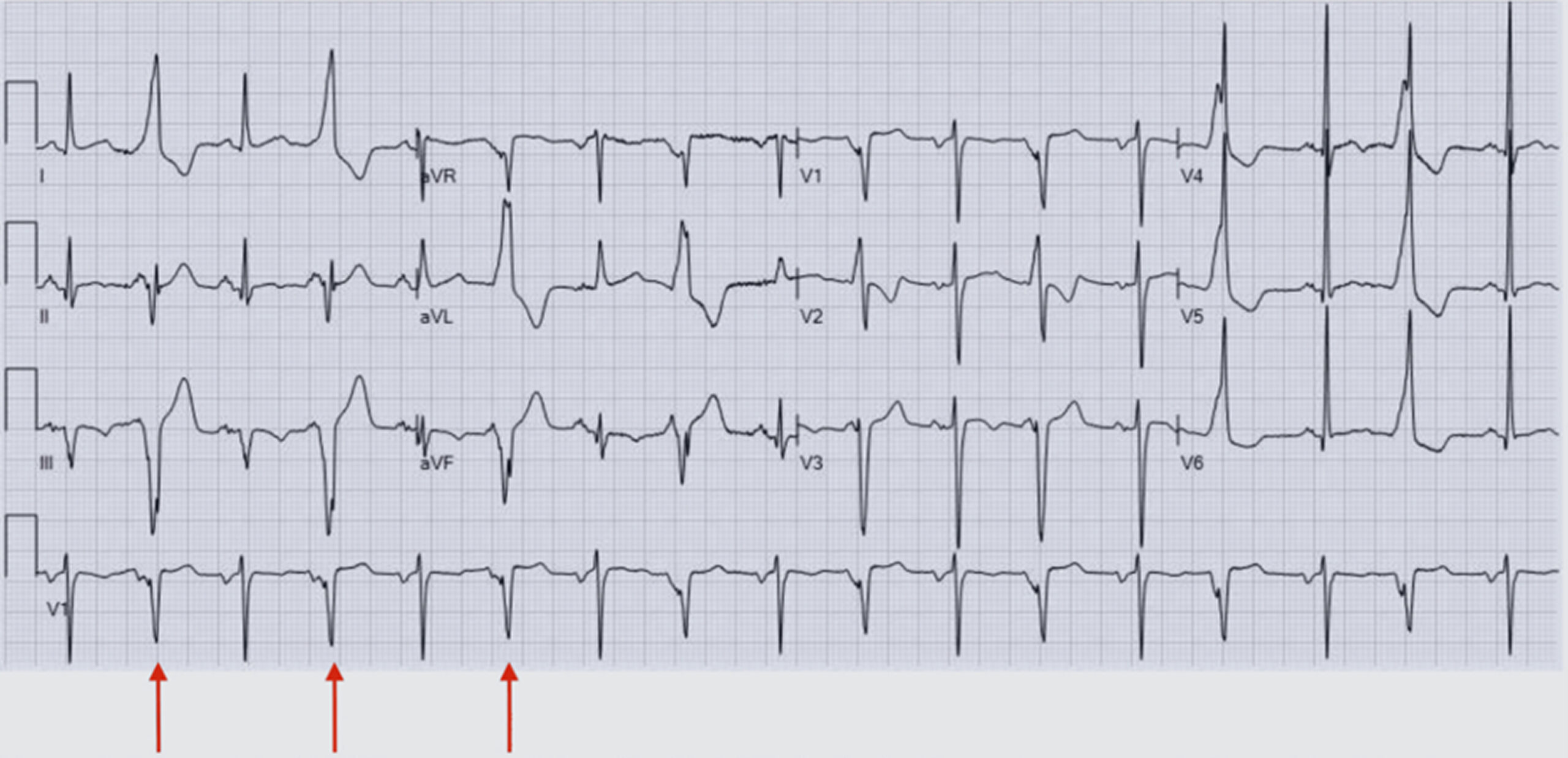

She reported intermittent hematemesis attributed to chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, though this was not contributory to her presentation. She endorsed unquantified weight loss. She appeared agitated and tremulous, consistent with adrenergic excess. In the hospital, she was given lorazepam 0.5 mg, a bolus of 1 L of intravenous (IV) normal saline (N/S), and magnesium sulfate 2 g to correct a low magnesium (Mg) level of 1.57 mg/dL. Her B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) at the time increased to 264.5 pg/mL, and her troponin levels were slightly elevated at 29, 25, then 17 NG/L. She was admitted to the cardiac care unit to rule out cardiac causes of her syncopal episode, given the lack of prodromal warning signs, and because of her EKG, which showed interpolated PVCs initially thought to be ventricular bigeminy (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Interpolated PVCs seen on this patient’s EKG, indicated by red arrows on the rhythm strip

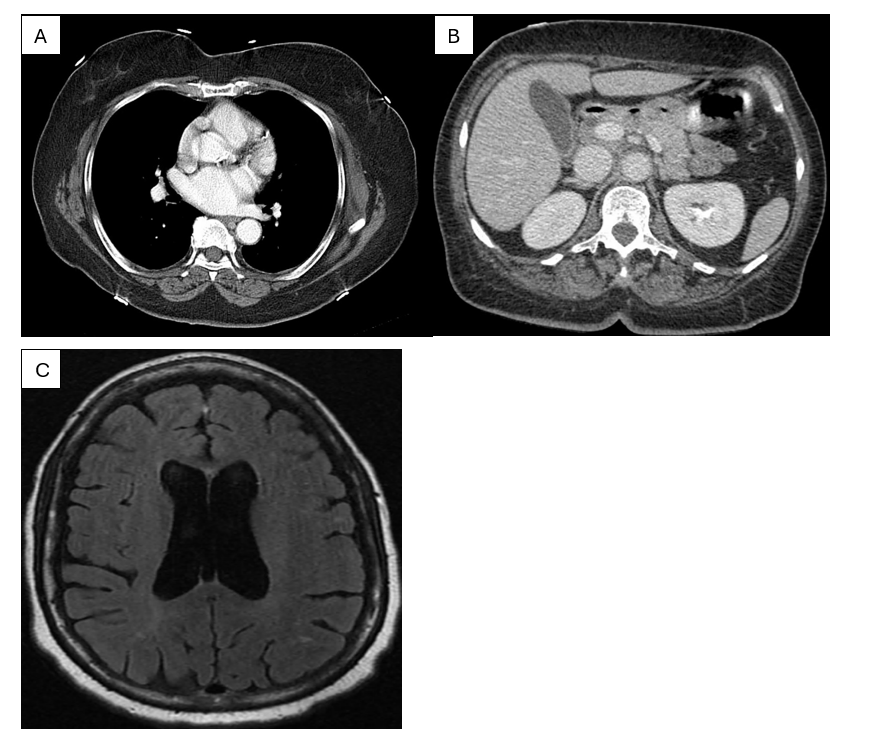

Figure 1 shows an occurrence between two sinus beats without a compensatory pause and a constant P-P interval. A chest x-ray was completed, showing no evidence of acute cardiopulmonary disease. A computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the chest was completed to rule out a pulmonary embolism. There was no evidence of pulmonary embolus, focal consolidation, pleural effusion, or pneumothorax. It was noted that she had three pulmonary nodules and that her thyroid was enlarged. An ultrasound of the abdomen was unremarkable, while the CT of the abdomen and pelvis showed minimal biliary dilation and moderate to severe atherosclerotic calcification of the abdominal aorta, but was otherwise unremarkable. A CT of the head without contrast was largely unremarkable for her age, showing no evidence of acute intracranial hemorrhage or definite infarction. There were nonspecific periventricular and subcortical white matter changes, which were likely to represent small-vessel ischemic disease, consistent with the patient’s age.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain to further evaluate her ongoing dizziness showed no evidence of acute territorial infarction, intracranial hemorrhage, or mass. The mid bilateral periventricular and deep white matter showed chronic microvascular ischemic changes and generalized cerebral atrophy. An echocardiogram was ordered and revealed a normal left ventricular cavity size and mildly increased left ventricular wall thickness. Global systolic function was low-normal global left ventricular contractility. Left ventricular ejection fraction of 50-55%. The right ventricle was mildly dilated. Right ventricular systolic function was normal. The aortic valve is a tri-leaflet valve. There was mild aortic stenosis (peak velocity 2.6m/s, mean gradient 15 mmHg, Doppler velocity index (DVI) = 0.60). There was no aortic regurgitation. The mitral leaflets were mildly thickened and calcified. Severe mitral annular calcification was present (posterior > anterior). There was reduced mobility of the posterior leaflet. There was mitral stenosis that was likely attributed to restricted leaflet motion in the setting of severe mitral annular calcifications (MAC).

Although assessing the degree of stenosis was difficult due to the patient’s heart rate in the 80s-90s, an estimated moderate severity was based on a mitral valve area of 2.4 cm² by planimetry. There was moderate, posteriorly directed mitral regurgitation due to restricted posterior leaflet motion in the setting of MAC. The tricuspid valve appeared structurally normal. There was mild to moderate tricuspid regurgitation. Right ventricular systolic pressure was estimated to be moderately elevated at 51mmHg. No prior studies were available for comparison. She underwent a nuclear stress test, which showed a fixed inferior defect consistent with prior infarction but no reversible ischemia.

During her stay at the cardiac care unit, she continued her atorvastatin 40mg once daily, was started on aspirin 81mg daily, and received metoprolol tartrate 12.5mg twice daily. Gastroenterology was consulted for the bloody emesis, and she was put on intravenous (IV) pantoprazole 40mg twice daily. During her work-up, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) was ordered, which showed a low TSH of <0.005 mU/mL. Moreover, levels for free triiodothyronine (free T3), free thyroxine (free T4), total thyroxine, and total triiodothyronine (total T3) were drawn and measured showing high free T3 at 19.82 PG/ML; high free T4 at 4.25 NG/DL; high thyroxine total at 21.07 MC/DL; and high total T3 at 457.0 NG/DL. Her thyroid peroxidase antibody was normal at 1IU/mL (reference range: <9); her thyroid receptor antibody was very elevated at >40.00IU/L (reference range: <=2.00), and her thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) was elevated at 389% baseline (reference range: <140). Her calcium was elevated at 11.7 MG/DL on admission, and her liver enzymes were also elevated.

Mild transaminase elevation was noted, consistent with thyrotoxicosis. Her results were suggestive of hyperthyroidism (Table 1), with a likely etiology of Graves’ disease and thyrotoxicosis. Endocrinology was consulted, and she was transferred to internal medicine for medical management. Methimazole 15 mg twice daily was initiated for the management of her hyperthyroidism. She was stabilized, then discharged, and will follow up with endocrinology outpatient for further management of hyperthyroidism.

Figure 2: (A) CT pulmonary angiogram demonstrating normal opacification of the pulmonary arteries with no evidence of pulmonary embolism. (B) Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT at the upper‐abdominal level showing normal enhancement of solid organs without acute pathology (C) Axial FLAIR MRI of the brain with normal ventricular morphology and no acute intracranial abnormality

| Lab test | Value | Reference range | Units |

| TSH | <0.005 | 0.4-4.0 | MU/ML |

| Free T3 | 19.82 | 2.3 – 4.2 | PG/ML |

| Free T4 | 4.25 | 0.8 – 1.9 | NG/DL |

| Thyroxine total | 21.07 | 4.5 – 12.5 | MC/DL |

| Total triiodothyronine | 457 | 82 – 179 | NG/DL |

| Calcium | 11.7 | 8.5-10.3 | MG/DL |

| Albumin | 4.57 | 3.2-5.5 | G/DL |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 146 | 30-130 | IU/L |

| Alanine transaminase | 80 | 0-55 | IU/L |

| Aspartate transaminase | 60 | 0-50 | IU/L |

| Total bilirubin | 0.6 | 0.2-1.2 | MG/DL |

| Thyroid peroxidase antibody | 1 | <9 | IU/mL |

| Thyroid receptor antibody | >40.00 | <=2.00 | IU/L |

| TSI | 389% | <140% |

Table 1: Thyroid function tests

Discussion

Thyrotoxicosis presents not only classic symptoms such as palpitations and weight loss, but also significant cardiac manifestations that can complicate diagnosis and management. Increasingly, the intricate relationship between thyroid hormones and cardiovascular health underscores the need to carefully assess thyroid function in patients with unexplained cardiac symptoms. Syncope may be the initial presentation of hyperthyroidism, as observed with head trauma due to an unprovoked syncopal event.[11]

Thyrotoxicosis can also manifest as recurrent syncope with rapid, wide QRS tachycardia.[12] In severe cases, thyrotoxicosis with pre-ventricular complexes can lead to thyroid storm and cardiac arrest.[13] While supraventricular arrhythmias are more common in thyrotoxicosis, ventricular arrhythmias, though rare, have also been reported. These cases emphasize the importance of considering thyroid dysfunction in patients presenting with syncope or cardiac arrhythmias. PVCs have been observed as a precursor to more severe arrhythmias in thyrotoxicosis.[13] In some cases, ventricular tachycardia and even ventricular fibrillation have been reported.[1] These arrhythmias often resolve with the achievement of a euthyroid state, suggesting a direct link between thyroid hormone excess and ventricular arrhythmogenesis.[1,13]

The potential for syncope related to arrhythmias complicated the clinical picture, especially since the patient presented without prodromal symptoms. The EKG findings suggested interpolated PVC with bigeminy, initially pointing toward a cardiogenic cause, as evidenced by this patient’s presentation. Hence, hyperthyroidism was not considered until a comprehensive workup that revealed markedly elevated levels of free T3 and T4, alongside suppressed TSH levels. The clinical findings were further corroborated by the detection of significant thyroid receptor antibody elevations and thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin, suggesting an underlying Graves’ disease etiology behind her syncope and high burden of PVCs with bigeminy. Our patient’s behavior, although overlooked initially, did confirm signs of hyperthyroidism, including tearful interviews, high levels of anxiety, and shallow breathing seemingly without provocation. Detection of underlying hyperthyroidism has profoundly altered the clinical course and management. To rule out cardiogenic causes, the patient had completed a 30-day event monitor after discharge and followed up with cardiology.

Her unique presentation with abnormal EKG findings made her incidental finding of hyperthyroidism something that could have been easily missed. Given the potential for syncope to be attributed to hyperthyroidism, timely recognition and treatment of thyrotoxicosis are essential to prevent severe complications, including thyroid storm and life-threatening arrhythmias. Prompt intervention with antithyroid medications, such as methimazole, should be prioritized in the management of hyperthyroid patients presenting with cardiac symptoms.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this case study reinforces the need for clinicians to maintain a high index of suspicion for thyroid dysfunction in patients with unexplained cardiac events to prevent further complications of arrhythmia. Hyperthyroidism can easily be underestimated as a potential cause of syncope, particularly when presentations do not conform to classic symptomatology. Our case underscores the significance of abnormal EKG findings, specifically interpolated premature ventricular contractions with ventricular bigeminy. Such findings are atypical for hyperthyroidism and occurred alongside untreated hyperthyroidism and thyrotoxicosis in our patient. This case highlights a possible expanded EKG presentation that warrants consideration when assessing the underlying etiology of syncope. We believe these insights will enhance the recognition and management of similar cases in the future, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

References

- Nadkarni PJ, Sharma M, Zinsmeister B, Wartofsky L, Burman KD. Thyrotoxicosis-induced ventricular arrhythmias. Thyroid. 2008;18(10):1111-1114. doi:10.1089/thy.2007.0307

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Ahmad M, Reddy S, Barkhane Z, Elmadi J, Satish Kumar L, Pugalenthi LS. Hyperthyroidism and the Risk of Cardiac Arrhythmias: A Narrative Review. Cureus. 2022;14(4):e24378. doi:10.7759/cureus.24378

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Furlan L, Jacobitti Esposito G, Gianni F, Solbiati M, Mancusi C, Costantino G. Syncope in the Emergency Department: A Practical Approach. J Clin Med. 2024;13(11):3231. doi:10.3390/jcm13113231

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Mond HG, Haqqani HM. The Electrocardiographic Footprints of Ventricular Ectopy. Heart Lung Circ. 2020;29(7):988-999. doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2020.01.002

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Marcus GM. Evaluation and Management of Premature Ventricular Complexes. Circulation. 2020;141(17):1404-1418. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042434

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Brusseau V, Tauveron I, Bagheri R, et al. Heart Rate Variability in Hyperthyroidism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3606. doi:10.3390/ijerph19063606

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Raguthu CC, Gajjela H, Kela I, et al. Cardiovascular Involvement in Thyrotoxicosis Resulting in Heart Failure: The Risk Factors and Hemodynamic Implications. Cureus. 2022;14(1):e21213. doi:10.7759/cureus.21213

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Tribulova N, Kurahara LH, Hlivak P, Hirano K, Szeiffova Bacova B. Pro-Arrhythmic Signaling of Thyroid Hormones and Its Relevance in Subclinical Hyperthyroidism. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(8):2844. doi:10.3390/ijms21082844

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Olanrewaju OA, Asghar R, Makwana S, et al. Thyroid and Its Ripple Effect: Impact on Cardiac Structure, Function, and Outcomes. Cureus. 2024;16(1):e51574. doi:10.7759/cureus.51574

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Tan Öksüz SB, Şahin M. Thyroid and cardiovascular diseases. Turk J Med Sci. 2024;54(7):1420-1427. doi:10.55730/1300-0144.5927

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Kaddis A, Tellez T. Thyrotoxicosis: an unusual cause of syncope. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(4):797.e5-797.e6. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2019.01.018

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Sivaram SK, Qasim WR. Thyrotoxicosis presenting as syncope and rapid wide QRS tachycardia: A case report. J Saudi Heart Assoc. 2019;31(3):111-113. doi:10.1016/j.jsha.2019.02.002

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Comim FV, Comim FV, Mujica LKS, et al. SUN-023 Changes in Microct Bone Density and Reduced Bone Formation in a “Postmenopausal” PCOS Rat Model. J Endocr Soc. 2020;4(Suppl 1):SUN-023. doi:10.1210/jendso/bvaa046.1728

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

None

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Miriam Michael

Department of Internal Medicine

University of Maryland, Baltimore, USA

Email: mmichael@som.umaryland.edu

Co-Authors:

Shahnoza Dusmatova, Kristin Slater, Shawn Meepagala, Raghav Veluri, Allen Washington, Girma Ayele, Mekdem Bisrat

Department of Internal Medicine

Howard University Hospital, Washington, DC, USA

Qasim Khurshid, Urooj Fatima

Department of Cardiology

Howard University Hospital, Washington, DC, USA

Sinead Bhagwandeen

Department of Cardiology

Broward Health Medical Center, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA

Authors Contributions

Shahnoza Dusmatova and Kristin Slater led the conceptualization, methodology, and original drafting of the manuscript. They were also involved in reviewing and editing alongside Girma Ayele, Sinead Bhagwandeen, Allen Washington, Shawn Meepagala, and Mekdem Bisrat. Shahnoza Dusmatova and Kristin Slater managed references. Supervision was provided by Qasim Khurshid, Urooj Fatima, and Miriam B. Michael. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Informed Consent

Informed consent for the publication of this case report and the accompanying radiology images was obtained, and all efforts were made to ensure the patient’s confidentiality and anonymity.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors listed above certify that they have no affiliations with, or involvement in, any organization or entity that has any financial or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Dusmatova S, Slater K, Meepagala S, et al. Hyperthyroidism Masquerading as Frequent Premature Ventricular Contractions with Bigeminy. medtigo J Emerg Med. 2025;2(4):e3092247 doi:10.63096/medtigo3092247 Crossref