Author Affiliations

Abstract

Background: Over the past decade, there has been a notable rise in allergic reactions involving both natural rubber latex (NRL) and specific plant-derived foods in Maryland, Washington, D.C., and Northern Virginia. This condition, known as latex-fruit syndrome (LFS), is characterized by immunologic cross-reactivity between latex proteins and structurally similar proteins found in certain fruits such as banana, avocado, and kiwi. A key mechanism involves plant chitinase enzymes that can trigger hypersensitivity in susceptible individuals. This study investigates regional trends in LFS from 2014 to 2023 and explores possible environmental influences.

Methodology: We conducted a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records between 2014 and 2023. Patients were identified based on International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) codes indicating latex or latex-fruit allergies. Data analysis focused on temporal trends and co-allergy patterns, including associations with shellfish allergy.

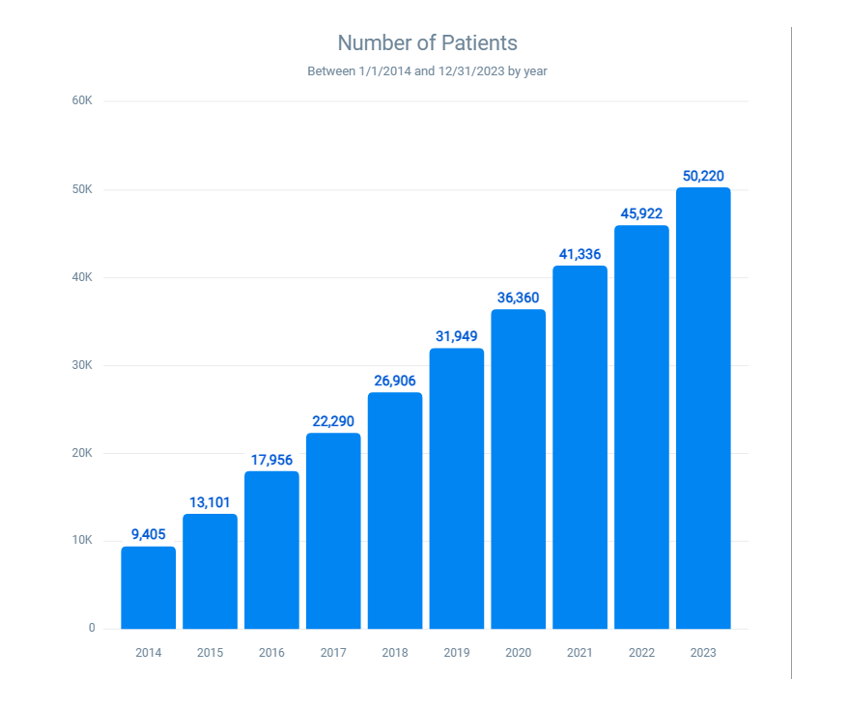

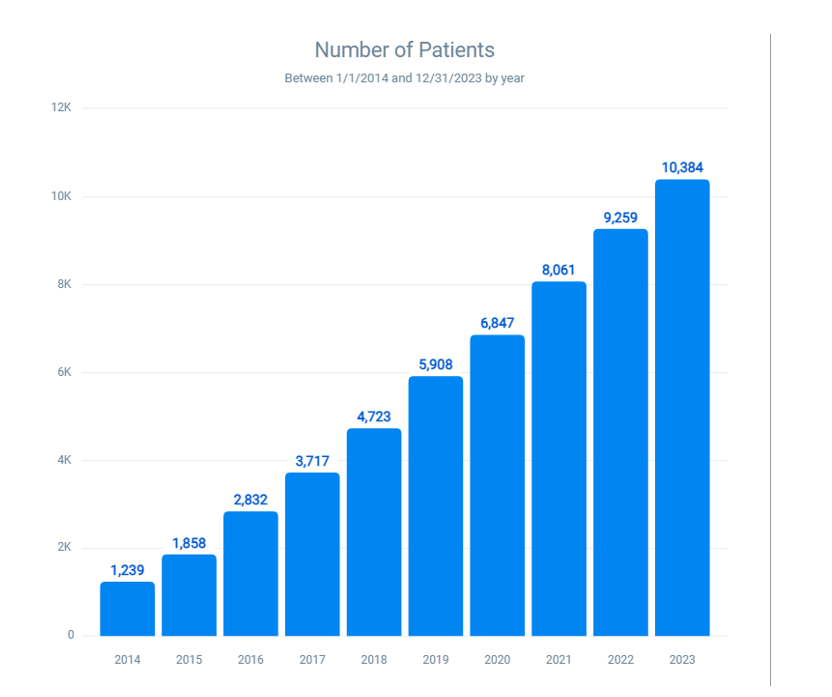

Results: The number of documented latex and latex-fruit allergy cases rose from 9,405 in 2014 to 50,220 in 2023, a 5.34-fold increase. Allergic reactions to cross-reactive fruits increased 8.38-fold. Co-sensitization to fruit and shellfish rose 6.67-fold, with the most pronounced surge, 10.27-fold, observed in individuals diagnosed with both latex and latex-fruit allergies.

Conclusions: This regional surge in LFS suggests a growing public health concern, potentially linked to increased exposure to plant-derived allergens, such as chitinases. Environmental factors such as climate change and agricultural shifts may play a role. Continued surveillance and further research are warranted to inform public health strategies and clinical management of food-related allergic disorders.

Keywords

Fruit Allergies, Rising temperature, Latex, Chitinase gene, Anaphylaxis.

Introduction

Latex-fruit syndrome occurs when individuals allergic to natural rubber latex also develop allergic reactions to certain fruits (kiwi, avocado, banana, papaya, and chestnut) due to similar allergenic proteins shared between latex and these fruits. People with this allergy may experience oral allergy syndrome, urticaria, angioedema, and in severe cases, anaphylaxis.[1] Recent studies indicate a notable correlation between increasing temperatures and the prevalence of latex-fruit allergies. As temperatures rose over the years, there was a corresponding increase in the incidence of these allergies. Conversely, when the temperature declined in 2018, there was a progressive decrease in latex-fruit allergy cases by 2020. However, when temperatures rose again post-2020, the number of allergy cases increased once more.[2]

While some individuals develop fruit allergies before becoming sensitive to latex, particularly after consuming raw fruits, this allergy is more commonly the initial sensitizing condition. This phenomenon is driven by IgE antibodies and often results in skin symptoms, including numbness, swelling, and tingling. In rare instances, systemic responses, such as anaphylaxis, may develop. Gastrointestinal issues, including nausea and diarrhea, have also been observed in some affected individuals.[3] Because there is currently no cure for food allergies, strict avoidance of allergenic foods remains the cornerstone of management.[4]

Globally, natural rubber latex allergy affects approximately 4.2% of the population, and its prevalence is significantly higher among healthcare professionals due to their repeated exposure to latex gloves and medical devices, with sensitization rates reaching as high as 13%.[5] However, over the past two decades, there has been a noticeable decline in latex allergy rates within healthcare settings, largely attributed to reduced reliance on latex-based products. Importantly, direct contact with latex is not always necessary to trigger a latex allergy. In some cases, consuming fruits that share allergenic proteins with latex can provoke similar allergic reactions. Latex-fruit syndrome (LFS) involves the same IgE-mediated mechanisms seen in oral allergy syndrome and reflects a shared immunologic response to latex and specific plant-based foods.[6]

Out of a total base population of 5,837,850 individuals assessed in 2014, there were 9,405 documented cases of latex or latex-fruit allergies. By 2023, this number had risen sharply to 50,220, representing a 5.34-fold increase in prevalence.[7] The sharp rise in latex allergy cases during the 1980s and 1990s coincided with increased use of latex gloves and condoms, particularly in response to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic. Other contributing factors include intensified rubber production processes that elevate allergen levels and the application of chemical agents to accelerate both rubber yield and fruit ripening. Ethylene-releasing substances used in agriculture and manufacturing have also been suggested as potential contributors.[8] Food allergies, including those associated with latex-fruit syndrome, are triggered by interactions between dietary proteins and IgE antibodies, although the exact molecular mechanisms that cause allergenicity are still being investigated.

The first known report of latex-fruit cross-reactivity dates to the early 1990s and involved a latex-allergic individual who also reacted to bananas. This link was confirmed through a radioallergosorbent test (RAST)-inhibition assay, a diagnostic tool for identifying IgE-mediated allergic responses.[9] Subsequent research, including a 1994 study involving 25 latex-allergic patients, demonstrated a high rate of fruit hypersensitivity among this population, lending strong support to the concept of latex-fruit syndrome.[10]

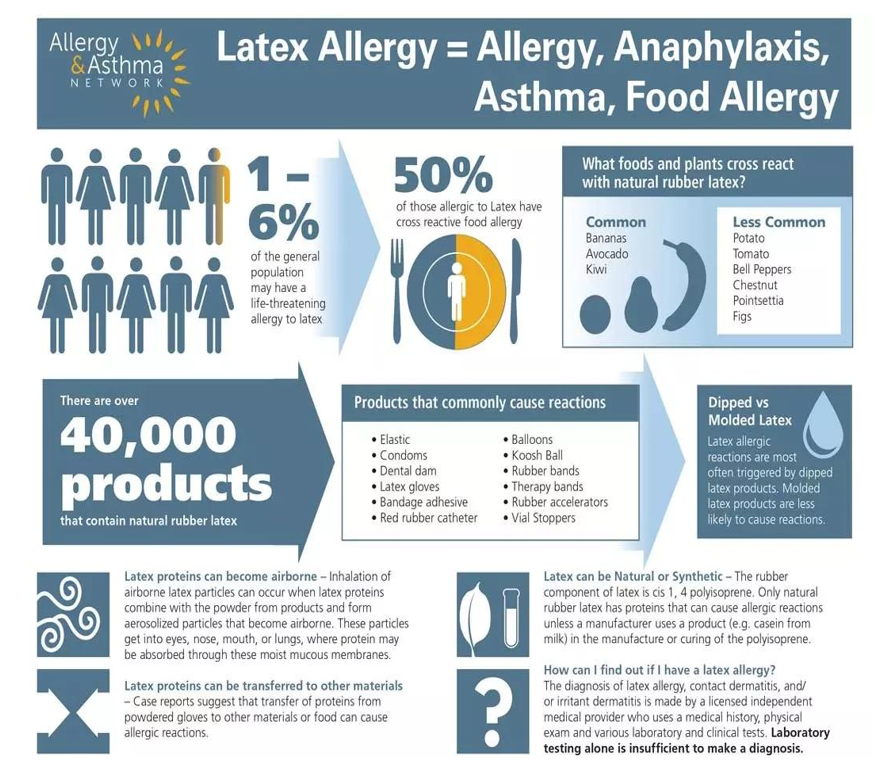

Figure 1: Products that commonly cause latex allergies (Image used with permission from the Allergy & Asthma Network)

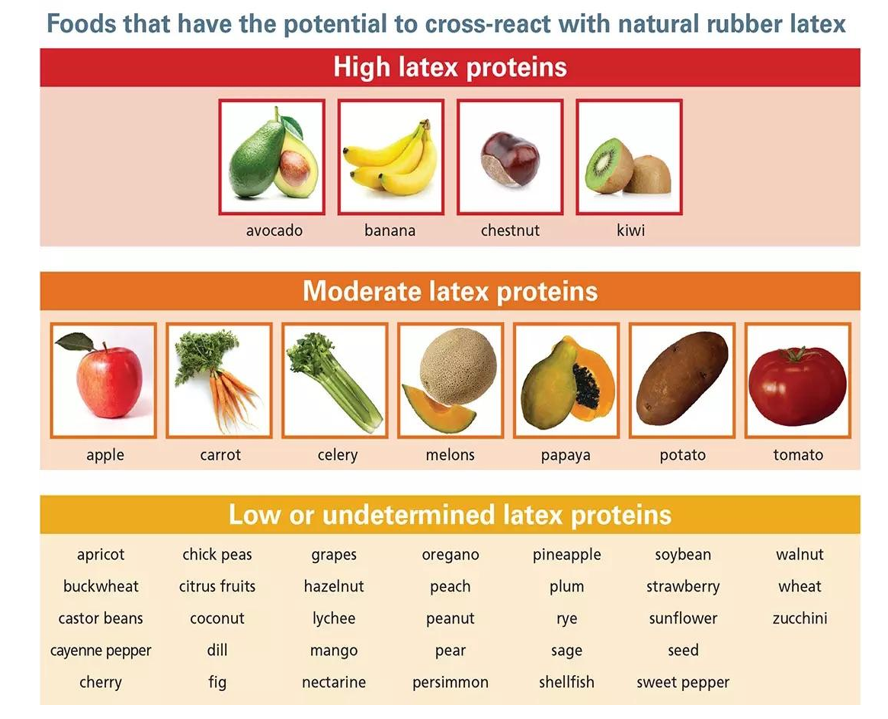

Studies have reported a wide range in the co-occurrence of latex and fruit allergies, with prevalence estimates varying from 21% to 58%. Brehler R and colleagues conducted a case-control study involving 150 patients with confirmed latex allergies and 30 non-allergic controls.[11] The results indicated that 42.6% of the latex-allergic group also reacted to fruits like kiwi and banana. Symptoms varied, with common complaints including gastrointestinal distress and fatigue, while some individuals experienced more serious reactions such as asthma or anaphylaxis.[12,13] Among the fruits most frequently associated with latex-fruit syndrome are bananas, chestnuts, and avocados. These fruits contain proteins that share structural similarities with those found in natural rubber latex, leading to immune cross-reactivity in susceptible individuals. Other fruits that may act as allergens, though less commonly, include kiwi, tomatoes, pineapples, passion fruit, mangoes, figs, and papayas. Over time, this syndrome has been associated with an increased number of plant sources, including avocado, banana, chestnut, kiwi, peach, tomato, potato, and bell pepper.[14] While it is typical for latex sensitivity to appear before food allergies, cases where fruit allergies develop first have also been documented. Additionally, research suggests that a significant number of individuals with latex allergies have a personal or family history of atopic conditions.[15]

Figure 2: Foods that react with latex allergies (Image used with permission of the Allergy and Asthma Network)

The allergic reactions observed in latex-fruit syndrome are thought to arise from a combination of cross-reactivity and direct sensitization. This is supported by evidence showing that Hev B proteins—specific latex allergens—can interact with plant defense proteins, especially Class I chitinases. A major allergenic component, hevein (part of Hev B 6), plays a central role in allergic responses involving both plant-derived and insect-related chitinases. Chitinases found in various fruits have structural similarities to hevein, a primary allergen present in the latex of the Hevea brasiliensis tree. Furthermore, these plant-based allergens also resemble chitinases from the house dust mite Dermatophagoides farinae, suggesting a broader spectrum of cross-reactivity.[16]

The association between latex sensitivity and plant-derived foods may also be influenced by agricultural practices, particularly the use of ethylene oxide, a chemical agent used to hasten fruit ripening. Ethylene oxide has been found to enhance the expression of Class I chitinases in plants, which may contribute to the rising occurrence of latex-fruit syndrome.

Methodology

Study design and data source: This study utilized a retrospective cohort design to analyze trends in latex and latex-fruit allergies over a 10-year period (2013–2023). The data was extracted from a large electronic medical record (EMR) database using the Slicer Dicer tool, an advanced feature within Epic Systems that enables customizable queries for population health research.

Study population: Patients were included if they had documented diagnoses of latex allergy, latex-fruit allergy, or related conditions, as defined by specific ICD-10 codes. Exclusion criteria included incomplete demographic data or misclassification of diagnoses.

Data extraction: Slicer Dicer was used to filter and stratify the patient population. The tool allowed for:

- Identification of patients based on the predefined ICD-10 codes.

- Stratification by age, sex, geographic region, and time of diagnosis.

- Analysis of trends in the incidence and prevalence of allergies.

Variables collected:

- Demographic information (age, sex, and geographic location)

- Year of diagnosis

- Association with specific latex-related exposures or latex-fruit cross-reactivity

Data slicing: The data for patients with latex and latex fruit allergy was further stratified (sliced) by the years 2014 to 2023 and the geographic area of Maryland.

Data analysis: Descriptive statistics were employed to outline the demographic and clinical profiles of the study population. To assess changes over time, temporal trend analysis was conducted, highlighting fluctuations in incidence and prevalence throughout the 10-year observation period.

Results

Out of a total base population of 5,837,850 individuals assessed in 2014, there were 9,405 documented cases of latex or latex-fruit allergies. By 2023, this number had risen sharply to 50,220, representing a 5.34-fold increase in prevalence (Figure 1). Allergic reactions to fruits known to contain moderate to high levels of latex-like proteins, such as avocado, banana, and kiwi, showed an 8.38-fold rise. Additionally, instances involving both fruit and shellfish allergies increased by 6.67 times, while cases of coexisting latex and latex-fruit allergies saw a 10.27-fold escalation over the study period.

Analysis of allergy data in Maryland, the District of Columbia, and Northern Virginia (2014-2023): This analysis examines the prevalence and trends in patients with latex and latex fruit allergies in Maryland, the District of Columbia, and Northern Virginia over the past decade (2014-2023). The data includes both self-reported cases and lab-confirmed diagnoses, encompassing a range of symptoms from intolerance and local side effects to systemic reactions and anaphylaxis.

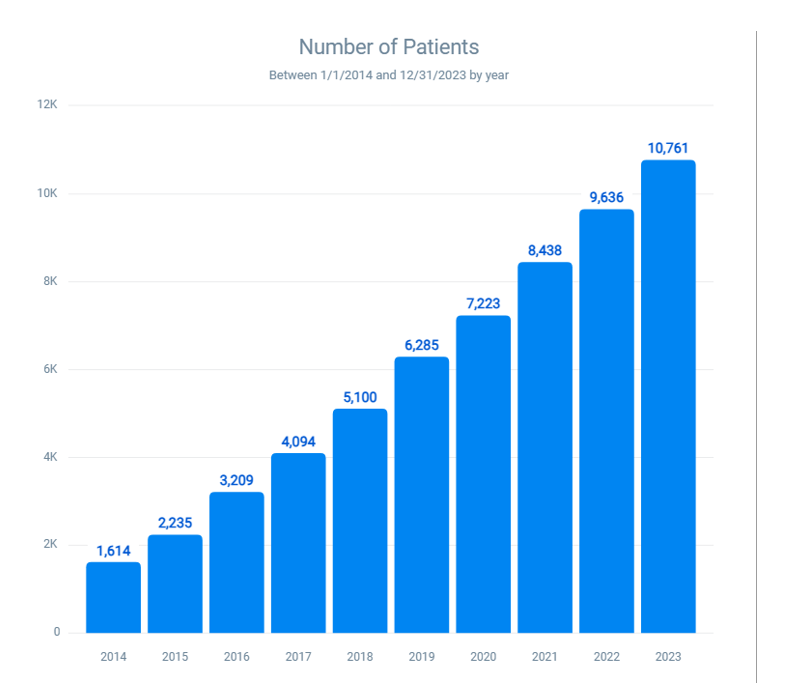

Overall trends in latex and latex fruit allergies: The number of patients with latex or latex fruit allergies has risen significantly from 9405 in 2014 to 50,220 in 2023 (Figure 3). This represents an increase of approximately 433.94%, or a 5.34-fold increase over the ten-year period. This sharp rise underscores the growing impact of these allergens on the population in the studied regions.

Figure 3: Ten-year trend in latex-fruit allergy cases

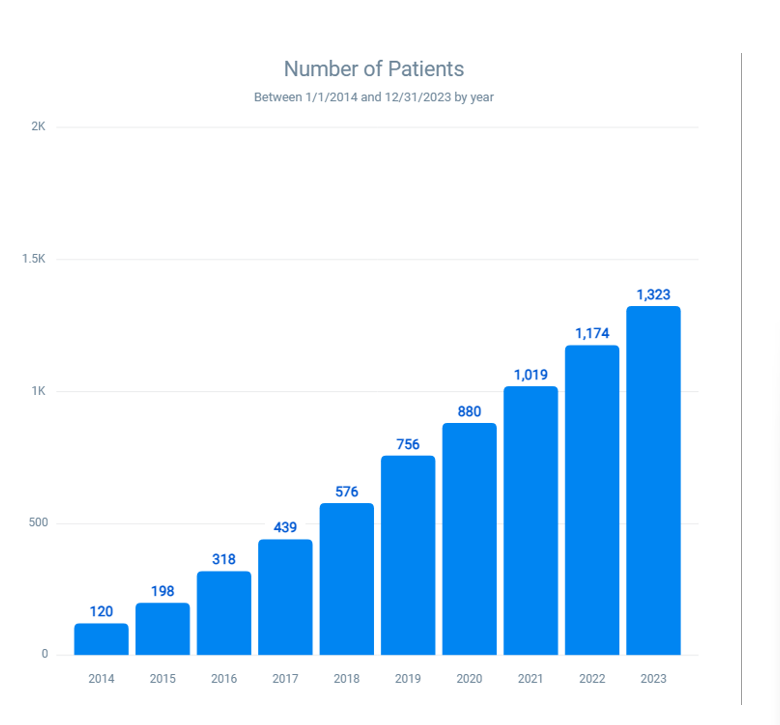

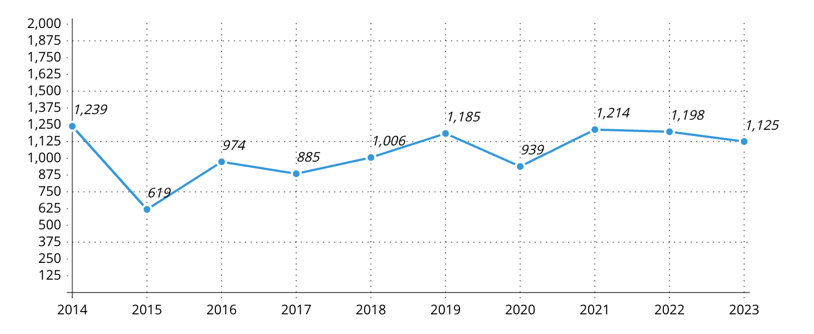

Specific allergies to fruits containing high to moderate latex protein (Avocado, banana, kiwi, apple, carrot, celery, melon, papaya, potato, and tomato): The reported cases of allergies to these fruits have increased from 1239 in 2014 to 10,384 in 2023 (Figure 4). This equates to an increase of about 738.21%, or an 8.38-fold increase over the decade. These fruits, known for their high to moderate latex protein content, have become more prevalent allergens, indicating a potential need for increased awareness and preventive measures.

Figure 4: Prevalence of allergies to fruits containing high to moderate latex proteins (Avocado, banana, kiwi, apple, carrot, celery, melon, papaya, potato, and tomato)

Specific allergies to latex-associated fruits and shellfish: The number of patients with combined allergies to fruits and shellfish rose from 1614 in 2014 to 10,761 in 2023 (Figure 5). This growth represents a 566.73% increase and a 6.67-fold increase over ten years. This trend suggests that individuals with latex fruit allergies may also be at risk for shellfish allergies.

Figure 5: Prevalence of allergies to latex-associated fruits (Avocado, banana, kiwi, apple, carrot, celery, melon, papaya, potato, and tomato) and shellfish

Combined latex and latex fruit allergies: The prevalence of patients with both latex and latex fruit allergies has surged from 120 in 2014 to 1323 in 2023 (Figure 6). This represents an approximate increase of 926.67%, or a 10.27-fold increase over the decade. This data indicates a critical rise in dual allergies, necessitating better diagnostic practices and management strategies to mitigate the risks of severe allergic reactions.

Figure 6: Prevalence of combined latex and latex-fruit allergies over 10 years

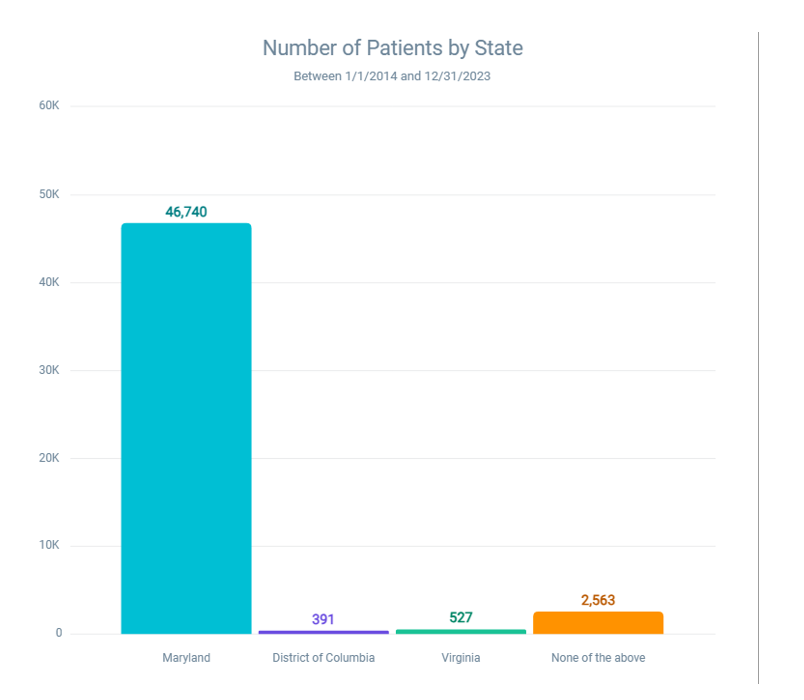

Figure 7: Distribution of patients with latex and latex-fruit allergy by state (Jan 1, 2014 – Dec 31, 2023)

Figure 7 illustrates the number of patients diagnosed with latex and latex-fruit allergies across different states over a 10-year period, from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2023. The data, derived from a base population of 5,842,708, reveals geographic variations in allergy prevalence, which may reflect differences in environmental exposures, healthcare access, or population demographics.

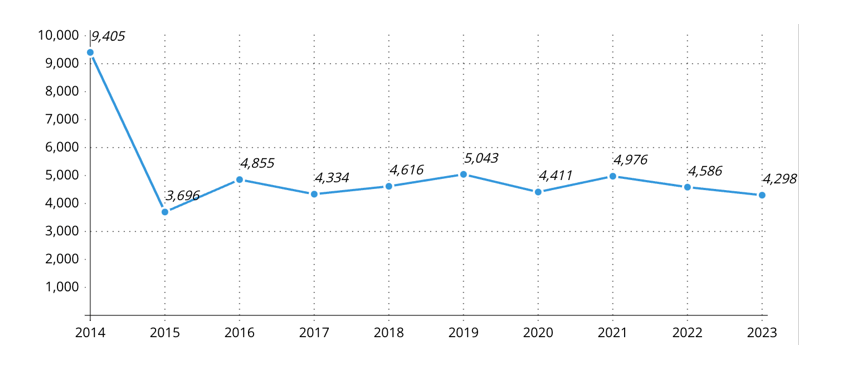

Figure 8: Incidence of patients with both self-reported and lab-confirmed latex or latex fruit allergy (Intolerance, local and systemic side effects, and anaphylaxis)

Figure 9: Incidence of allergy to fruits containing high to moderate latex protein (Avocado, banana, kiwi, apple, carrot, celery, melon, papaya, potato, and tomato)

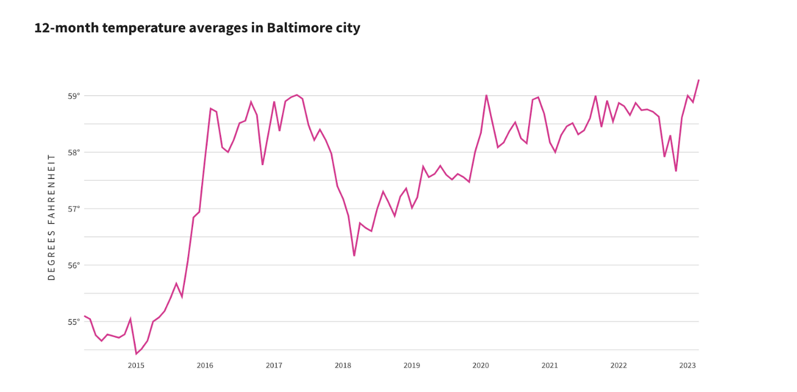

Figure 10: Baltimore city average temperatures by month (12-month period)

Environmental data from the National Centers for Environmental Information provided the figure. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution, and production in any medium or format, if you give appropriate credit to the original authors and source.

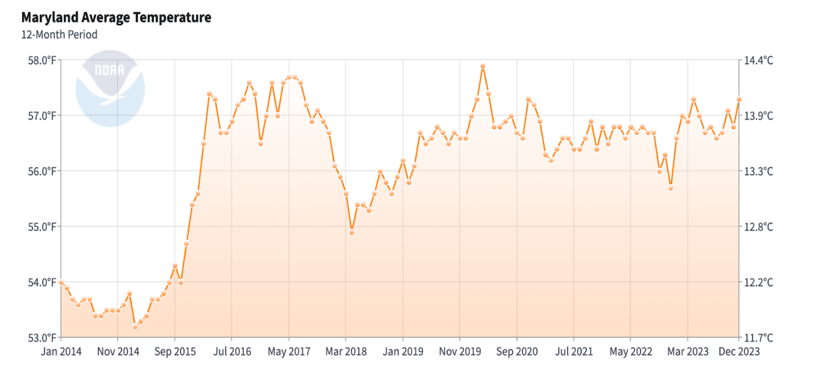

Figure 11: Maryland average temperature

Baltimore and the state of Maryland have seen an increase in peak temperatures. The summer months have recorded higher maximum temperatures compared to a decade ago, reflecting a trend of increasingly hotter summers. The average annual temperature in Baltimore and the state of Maryland has also shown an upward trend. This aligns with global climate change patterns, where average temperatures are rising due to increased greenhouse gas emissions.[17]

Discussion

Over the past decade, the incidence of latex and latex fruit allergies in Maryland, the District of Columbia, and Northern Virginia has exhibited a significant upward trend. This increase is reflected in both self-reported cases and lab-confirmed diagnoses, highlighting a range of allergic reactions from intolerance and local side effects to systemic reactions and anaphylaxis.

Our results indicate a notable correlation between increasing temperatures and the prevalence of latex fruit allergies. As temperatures rose over the years, there was a corresponding increase in the incidence of these allergies. Conversely, when the temperature declined in 2018, there was a progressive decrease in latex fruit allergy cases by 2020. However, when temperatures rose again post-2020, the number of allergy cases increased once more. This pattern suggests that higher temperatures may enhance plant growth and pollen production, leading to greater exposure and sensitization to allergens. Further research is needed to establish causality, explore other contributing factors, and examine geographical variations in this trend.

Historically, the adoption of gloves in healthcare settings to mitigate the spread of AIDS in the 1980s led to a significant rise in IgE-mediated allergies to NRL, with about 15% of medical personnel in Europe and the US becoming sensitive to NRL. This risk was notably higher among patients with congenital malformations and children with multiple surgical interventions, particularly those with spina bifida, where the sensitivity rate reached approximately 50%. However, this number has drastically decreased to less than 5% as the use of natural latex products in medical devices and gloves has diminished over the past few decades.[18]

The previously declining trend in latex-related allergies now appears to be reversing, likely due to increased exposure to foods rich in latex-like proteins and the heightened concentration of these proteins in both food and commercial products. A key factor in this resurgence is the presence of allergens in NRL, particularly chitinases. Chitin, a structural polysaccharide second only to cellulose in abundance, is found in fungi, yeast, algae, and invertebrate exoskeletons. Plants produce chitinase enzymes to break down chitin as part of their defense against fungal and arthropod threats. Notably, Class I chitinases are heat-sensitive, which may explain why cooking plant-based foods often reduces their potential to trigger allergic reactions.[19]

The physiological role of chitinases as pathogenesis-related proteins is crucial, particularly since they are expressed at low levels in plants and induced in response to stress or pathogen attack. Recent climate-related stressors may exacerbate this risk for allergic individuals. Besides the natural upregulation in response to pathogens, chitinase genes have been cloned and expressed in various plants to enhance disease resistance. For example, introducing a Class I chitinase gene from potatoes into tea improved resistance to blister blight disease, and expressing a rice chitinase gene in wheat conferred resistance against stripe rust disease. Increased resistance to Fusarium head blight was also achieved by expressing a barley Class II chitinase gene in wheat.[20-22]

Morphological acclimation responses to elevated ambient temperatures, known as thermomorphogenesis, involve increased chitinase expression under various abiotic stresses, including drought, ozone, and osmotic stress.[23] These stresses contribute to the systemic induction of chitinases, which have been identified as major pan-allergens in fruits associated with LFS. The rising global temperatures may further intensify this issue, leading to a resurgence of LFS incidents.

Conclusion

The analysis of allergy data from Maryland, the District of Columbia, and Northern Virginia over the past ten years illustrates a significant rise in latex and latex fruit allergies. The substantial percentage increases and fold changes underscore the growing public health burden of these allergies. This trend necessitates continued monitoring, research, and public health initiatives to address the rising prevalence and develop effective prevention and management strategies.

The correlation between climate change and increased allergy prevalence is particularly noteworthy. Higher peak and average temperatures in the region have been recorded over the past decade, reflecting global climate change patterns. These climatic changes influence the prevalence and severity of allergies, complicating public health responses. Environmental temperatures affect plant growth and stress responses, leading to the upregulation of chitinases, which are significant allergens. As global temperatures rise, the associated stressors may increase the risk of allergic reactions, emphasizing the need for integrated approaches to manage and mitigate the impact of climate change on public health.

References

- Wagner S, Breiteneder H. The latex-fruit syndrome. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30(6):935-940. doi:10.1042/bst0300935 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gromek W, Kołdej N, Świtała S, Majsiak E, Kurowski M. Revisiting Latex-Fruit Syndrome after 30 Years of Research: A Comprehensive Literature Review and Description of Two Cases. J Clin Med. 2024;13(14):4222. doi:10.3390/jcm13144222 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Brehler R, Theissen U, Mohr C, Luger T. “Latex-fruit syndrome”: frequency of cross-reacting IgE antibodies. Allergy. 1997;52(4):404-410. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.1997.tb01019.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Leoni C, Volpicella M, Dileo M, Gattulli BAR, Ceci LR. Chitinases as Food Allergens. Molecules. 2019;24(11):2087. doi:10.3390/molecules24112087 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Allergy & Asthma Network. Complete guide to latex allergy. 2020. Complete guide to latex allergy

- Brehler R, Kütting B. Natural rubber latex allergy: a problem of interdisciplinary concern in medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(8):1057-1064. doi:10.1001/archinte.161.8.1057 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kim KT, Hussain H. Prevalence of food allergy in 137 latex-allergic patients. Allergy Asthma Proc. 1999;20(2):95-97. doi:10.2500/108854199778612572 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Breiteneder H, Scheiner O. Molecular and immunological characteristics of latex allergens. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1998;116(2):83-92. doi:10.1159/000023930 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Fritsch R, Ebner C, Kraft D. Allergenic crossreactivities. Pollens and vegetable foods. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 1997;15(4):397-404. doi:10.1007/BF02737735 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Blanco C. Latex-fruit syndrome. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2003;3(1):47-53. doi:10.1007/s11882-003-0012-y PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Schuirmann DJ. A comparison of the two one-sided tests procedure and the power approach for assessing the equivalence of average bioavailability. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1987;15(6):657-680. doi:10.1007/BF01068419 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Vieths S, Scheurer S, Ballmer-Weber B. Current understanding of cross-reactivity of food allergens and pollen. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;964:47-68. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04132.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lavaud F, Prevost A, Cossart C, Guerin L, Bernard J, Kochman S. Allergy to latex, avocado pear, and banana: evidence for a 30 kd antigen in immunoblotting. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;95(2):557-564. doi:10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70318-7 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Zinabu SW, Mohammed A, Ayele GM, et al. Latex Fruit Syndrome as a Case of a Lower GI Bleed. Cureus. 2024;16(7):e65002. doi:10.7759/cureus.65002 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hamid R, Khan MA, Ahmad M, et al. Chitinases: An update. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2013;5(1):21-29. doi:10.4103/0975-7406.106559 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- National Centers for Environmental Information. Statewide Time Series. Published May 2025. Accessed on June 5, 2025. Statewide Time Series

- Hoffmann-Sommergruber K. Pathogenesis-related (PR)-proteins identified as allergens. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30(Pt 6):930-935. doi:10.1042/bst0300930 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ding Y, Shi Y, Yang S. Molecular Regulation of Plant Responses to Environmental Temperatures. Mol Plant. 2020;13(4):544-564. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2020.02.004 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kumar M, Brar A, Yadav M, Chawade A, Vivekanand V, Pareek N. Chitinases—Potentialdidates for enhanced plant resistance towards fungal pathogens. Agriculture. 2018;8(7):88. doi:10.3390/agriculture8070088 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Singh HR, Deka M, Das S. Enhanced resistance to blister blight in transgenic tea (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze) by overexpression of class I chitinase gene from potato (Solanum tuberosum). Funct Integr Genomics. 2015;15(4):461-480. doi:10.1007/s10142-015-0436-1 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Huang X, Wang J, Du Z, Zhang C, Li L, Xu Z. Enhanced resistance to stripe rust disease in transgenic wheat expressing the rice chitinase gene RC24. Transgenic Res. 2013;22(5):939-947. doi:10.1007/s11248-013-9704-9 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Shin S, Mackintosh CA, Lewis J, et al. Transgenic wheat expressing a barley class II chitinase gene has enhanced resistance against Fusarium graminearum. J Exp Bot. 2008;59(9):2371-2378. doi:10.1093/jxb/ern103 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Delker C, Quint M, Wigge PA. Recent advances in understanding thermomorphogenesis signaling. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2022;68:102231. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2022.102231 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge and extend my gratitude to the authors who gave permission for the images. Their work has significantly contributed to the illustration and depth of my article. Thank you for allowing me to share and build upon your creative efforts.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit 33sectors.

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Ayushi Sen

Department of Internal Medicine

Howard University, Washington DC, USA

Email: michaelclarkfamily@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Samrawit Zinabu, Mekdem Bisrat, Sair Ahmad Tabraiz, Elizabeth Beyene, Allen Washington, Mahlet Abrie, Ahmed Mohammed, Noah Wheaton, Christian Wong, Anand Deonarine

Department of Internal Medicine

Howard University, Washington DC, USA

Miriam Michael

Department of Nephrology

Howard University, School of Medicine, University of Maryland, American University of Antigua College of Medicine, USA

Authors Contributions

Ayushi Sen contributed to the conceptualization, writing, and reviewing of the document. Samrawit Zinabu was involved in conceptualization and writing. Mekdem Bisrat and Sair Ahmad Tabraiz participated in reviewing and editing the document. Allen Washington contributed to refining the content, while Ahmed Mohammed focused on editing. Mahlet Abrie and Noah Wheaton were involved in conceptualizing and drafting the document. Christian Wong contributed to drafting, and Anand Deonarine was involved in writing the document. Miriam Michael played a key role in conceptualization and supervision.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted using retrospective, de-identified electronic health record data and did not involve any direct interaction with patients or the collection of identifiable personal information. In accordance with institutional policies and federal regulations (45 CFR 46.102 and 46.104), this research qualifies as non-human subjects research and therefore did not require formal Institutional Review Board (IRB) review or approval. All data were analyzed in compliance with relevant data protection and privacy regulations.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Sen A, Zinabu S, Bisrat M, et al. Hotter Days, Stronger Reactions: The Climate-Allergy Connection. medtigo J Med. 2025;3(2):e30623224. doi:10.63096/medtigo30623224 Crossref