Author Affiliations

Abstract

Lawsonia inermis, or henna, is traditionally used in Ayurvedic medicine for its hepatoprotective properties. This study explores its protective effects against lead acetate-induced liver injury in Wistar rats. Thirty-five adult rats were divided into seven groups: Group I (control) received distilled water; Group II received Lawsonia inermis; Group III received lead acetate; Group IV received lead acetate along with 70 mg/kg of silymarin; Groups V and VI received lead acetate alongside 200 mg/kg and 400 mg/kg of Lawsonia inermis, respectively; Group VII received 400 mg/kg of Lawsonia inermis followed by lead acetate after 30 minutes. After 28 days, the rats were sacrificed for analysis. Significant weight increases were observed in Groups IV, V, and VI. The liver body weight index was highest in the control group. Lead treatment led to significant increases in total bilirubin and decreases in aspartate transferase levels. Importantly, treatment with Lawsonia inermis and silymarin reduced the harmful effects of lead exposure, with the 400 mg/kg dose of Lawsonia inermis showing the highest efficacy. Histological analysis confirmed the extract’s ability to mitigate lead-induced liver damage.

Keywords

Lawsonia inermis, Hepatoprotective, Lead acetate, Wistar rats, Ayurvedic medicine.

Introduction

Lawsonia inermis (Henna) is a valuable medicinal plant globally. Its leaf powder is commonly used for staining hair, nails, and beards.[1] In Southwestern Nigeria, the leaves are utilized by the Yoruba tribe to treat poliomyelitis and measles.[2] The seeds possess deodorant properties and are applied in cases of gynecological disorders such as menorrhagia and leucorrhea.[3] Additionally, a paste made from equal parts of the leaves of Lawsonia inermis, Hibiscus rosa-sinensis, Eclipta prostrata, and Abrus precatorius seeds, soaked in sesame oil, is used as hair oil in Andhra Pradesh, India.[4] In Turkey, henna serves as a decorative dye for hair and nails[5], and it is widely utilized in the cosmetic industry in India.[1] Methanolic root extracts of Lawsonia are reported for cosmetic purposes and antimalarial properties in Nigeria[6], as well as for abortifacient uses.[7] A paste made from roasted seeds and ginger oil treats ringworm, while leaf decoctions are employed for wound cleaning and healing.[8] Moreover, L. inermis is used as a ‘blood tonic’, highlighting its broad applications.[6]

The L.inermis plant is a branching shrub or small tree, typically 2-6 meters high, with quadrangular, green young branches that redden with age. Its leaves are opposite, entire, elliptic to lanceolate, and glabrous, measuring 1.5-5 x 0.5-2 cm. Flowers are small, white, and fragrant, arranged in large pyramidal clusters, with a characteristic size of 1 cm.[8] The plant is distributed across the Sahel, Central Africa, and the Middle East, thriving in waterways and semi-arid regions, and is able to tolerate low humidity and drought.[9]

Lead (II) acetate (Pb (CH3COO)2), also known as lead acetate or lead sugar, is a white crystalline compound with a slightly sweet taste.[10] It is toxic and soluble in water and glycerin, forming a trihydrate.[11,12] Lead acetate serves as a reagent for synthesizing other lead compounds and is a fixative in dyeing.[13] In lower concentrations, it is utilized as an active ingredient in hair dyes, as well as a mordant in textile printing and dyeing, and a drier in paints.[14] Historically, it was also used as a sweetener in wines and foods and in cosmetics. This study investigates the hepatoprotective effects of aqueous extracts of Lawsonia inermis against lead acetate-induced liver injury in Wistar rats, including the liver enzymes and histological architecture of the liver.

Methodology

Collection and identification of plant: The leaves of L. inermis were obtained from Uselu Market in Egor local government area, Edo state, Nigeria. The plant was identified and authenticated by a plant taxonomist at the department of plant biology and biotechnology, faculty of life sciences, University of Benin, Benin city, Edo state, Nigeria.

Experimental animals: Thirty Wistar rats of weight between 167-204g were purchased from the department of human anatomy, University of Benin, Edo state. The animals were kept in the animal holding of the department of human anatomy for two weeks to acclimate. They were housed in well-ventilated aluminium cages at room temperature in hygienic conditions under a natural light (13 hours) and dark (11 hours) schedule and were fed on a standard laboratory diet. Food and water were given ad libitum. The research ethical committee of the college of medical sciences, University of Benin’s guidelines for animal handling and treatment were fully implemented.

Preparation of plant extract: Aqueous extraction of the plant was done by cold water maceration. 5kg of L. inermis leaves were washed with tap water, shade dried, and then pounded. The powder obtained was soaked in distilled water for 24 hours in a separating funnel with occasional shaking. The solution was then filtered. The filtrate was allowed to settle and then decanted. The decant was placed in an evaporating dish and then put in a water bath at 60 °C for excess water to evaporate gently, after which the dried residue, which was equal to 20% yield (1kg) of the crude extract, was scraped out and stored in a refrigerator.

Experimental design: The thirty-five (35) rats were assigned to five groups with five (5) animals each, using the block method, with an average weight of 187.2g across the groups

| Group I: | Negative control group: Rats were given distilled water (2ml) for 28 days |

| Group II: | Rats were given 400mg/kg of L. inermis only for 28 days. |

| Group III: | Rats were given 100mg/kg of Lead acetate only for 28 days. |

| Group IV: | Rats were given 100mg/kg of Lead acetate for 14 days and treated with 70mg/kg of Silymarin for 14 days. |

| Group V: | Rats were given 100mg/kg of Lead acetate for 14 days and treated with 200mg/kg of L. inermis for 14 days (low dose). |

| Group VI: | Rats were given 100mg/kg of Lead acetate for 14 days and treated with 400mg/kg of L. inermis for 14 days. |

| Group VII: | Rats were first given 400mg/kg of L. inermis and then administered 100mg/kg of Lead acetate after 30min for 28 days. |

Table 1: Evaluating the efficacy of L. inermis and Silymarin in ameliorating lead acetate toxicity in rats

All administrations were done by gavage and lasted for twenty-eight (28) days.

Administration: The Lawsonia inermis, lead acetate, and silymarin were given using a gavage with an orogastric tube. The rats were carefully handled to minimize oral or oesophageal injuries.

Tissue collection, processing and staining, histopathology: The rats were sacrificed, and the liver was taken at the end of the four weeks study. Blood (5 mL) was collected in sterile bottles for analysis of liver enzymes test and was immediately sent to the University of Benin teaching hospital’s chemical pathology department for biochemical testing. The liver tissue was preserved for 24 hours in 10% buffered formalin before being histologically processed and stained with haematoxylin and eosin using standard procedures.[15] The sections obtained were examined, and photomicrographs were taken using a Leica DM750 research microscope with an attached digital camera (Leica CC50). The tissues were photographed digitally at magnifications of x100.

Statistical analysis: Data were subjected to statistical analysis using IBM statistics package for science and social science (SPSS) software (version 20). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out, followed by the least significant difference (LSD) post-hoc test to determine the pairwise difference between groups. Data were presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. the p-value for each comparison is reported in the respective figures.

NB: Sim in the bar chart means Sample of Lawsonia inermis.

Results

Note: Bar-chart means a Sample of Lawsonia inermis

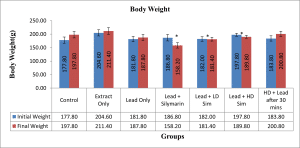

Values are given as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05 compared with initial weight.

Figure 1: Showing the difference between initial and final Body weight after 28 days of administration across all groups

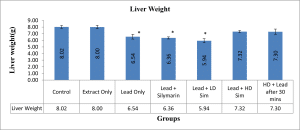

Values are given as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05 compared with control.

Figure 2: Showing Liver weight after 28 days of administration across all groups

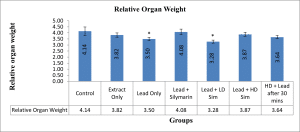

Values are given as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05 compared with control.

Figure 3: Showing Relative organ weights after 28 days of administration across all groups

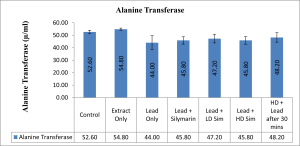

Values are given as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05 compared with control.

Figure 4: Showing the level in (µ/ml) of Alanine Transferase across all groups after 28 days of administration.

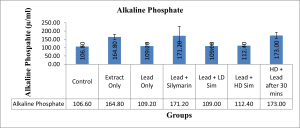

Values are given as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05 compared with control.

Figure 5: Showing the level in (µ/ml) of Alkaline Phosphate across all groups after 28 days of administration.

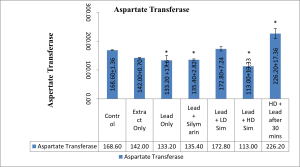

Values are given as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05 compared with control.

Figure 6: Showing Aspartate Transferase level after 28 days of administration across all groups

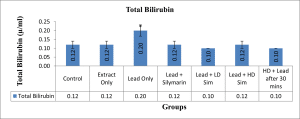

Values are given as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05 compared with control.

Figure 7: Showing Total Bilirubin level after 28 days of administration across all groups

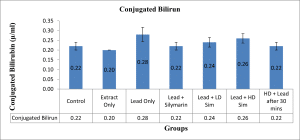

Values are given as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05 compared with control.

Figure 8: Showing level in (µ/ml) of Conjugated Bilirubin across all groups after 28 days of administration.

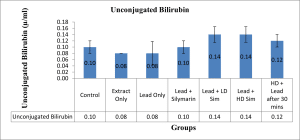

Values are given as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05 compared with control.

Figure 9: Showing level in (µ/ml) of Unconjugated Bilirubin across all groups after 28 days of administration.

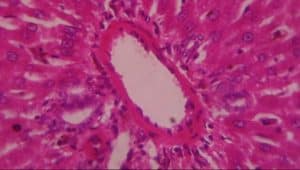

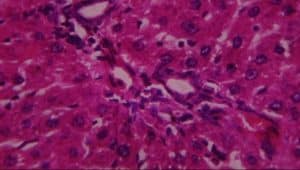

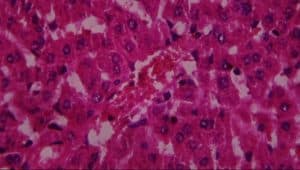

Figure 10: Liver (control) composed of A-hepatocytes, B-sinusoids, C-portal vein and D-bile duct (H&E x 400)

Figure 11: Rat given extract only showing A-normal hepatocytes, B-mild periportal infiltrates of inflammatory cells and C-Kupffer cell activation (H&E x 400)

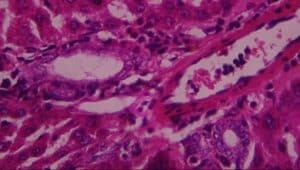

Figure 12: Rat given lead acetate only showing: A-vascular ulceration, B-periportal infiltrates of inflammation, C-vascular congestion and D-necrosis (H&E x 400)

Figure 13: Rat given Pb Acetate + Silymarin showing: A-normal hepatocytes and B-kupffer cell activation (H&E x 100)

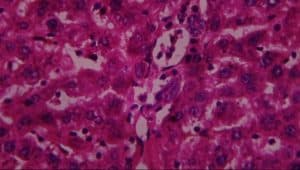

Figure 14: Rat given lead acetate + 200mg extract showing A-normal hepatocytes, B-active vascular congestion and C-Kupffer cell activation (H&E x 400)

Figure 15: Rat given lead acetate + 400mg extract showing A-normal hepatocyte and B-kupffer cell activation (H&E x 400)

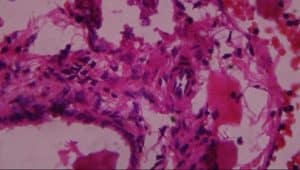

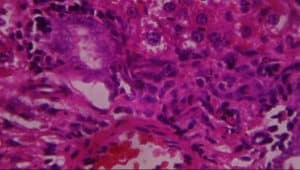

Figure 16: Rat given 400mg extract + lead acetate showing A-periportal infiltrates of inflammatory cells, B-vascular congestion, and C-patchy hepatocyte necrosis (H&E x 400)

Discussion

An increase in body weight was observed in all the groups compared to the control group, though a significant increase was observed in groups that received Lead plus Silymarin, Lead plus Low dose extract simultaneously, and Lead plus High dose extract simultaneously. This suggests that aqueous extract of L. inermis like silymarin helped protect against lead toxicity and does not affect food intake. It has been argued that an increase or decrease in either absolute or relative weight of an organ after administering a chemical or drug is an indication of the toxic effect of that chemical.[16]

In this present study, it was also observed that the liver weight significantly decreased in groups iii, iv and v as compared with control. Disagreeing with the findings of Ibrahim et al.[17] that increased body weight was observed in rats treated with lead acetate and attributed the increase to the accumulation of lipids in the organ.[18]

Lead is one of the most toxic heavy metals of great public health significance. Exposure to low-level heavy metals such as lead may contribute much more toward the causation of chronic diseases (diabetes, renal disease, cancer, male infertility, etc.) and impaired functioning than previously thought.[19] Available antidotes for lead poisoning, like chelators, have many adverse effects, such as being painful, hepatotoxic, and displaying gastrointestinal symptoms, among others. Some chelators are not only difficult to administer, but they are also expensive and not readily available. Also, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends that chelator therapy be used only in extreme cases where the blood lead level is over 45µg/dL. It is generally not used in cases where levels are under 25µg/dL, and it neither removes all the lead from the body nor does it undo damage already done to the organ. Lawsonia inermis is thus investigated in this study as a possible alternative to the classical therapy owing to the limitations. As a further justification for this research, there is currently sparse information on the efficacy of Lawsonia inermis in the treatment of lead poisoning.

In this study, treatment of rats with lead acetate resulted in a significant increase in the serum activity of total bilirubin, with a significant decrease in the serum activity of aspartate transferase. Similar result of bilirubin increase had earlier been reported.[20] The significant increase in total bilirubin was demonstrated to be reversed by treatment with aqueous extract of L. inermis. The increase in bilirubin value in rats treated with lead acetate in this study may be due to excessive heme destruction and blockage of the biliary tract, resulting in the inhibition of the conjugation reaction and release of unconjugated bilirubin from the damaged hepatocyte.[21] Bilirubin has a protective role against oxidative damage to the cell membrane induced by metal.[22] Besides, this study demonstrated a significant decrease in the value of serum aspartate transferase following oral administration of lead acetate to the stipulated rats. Administration of aqueous extract of L. inermis in high dose, along with Lead acetate, after 30 minutes was able to significantly increase the level of the enzyme aspartate transferase. A decrease in the value of serum AST observed in this study might be due to hepatic damage induced by lead, as earlier demonstrated[23], or might be due to lead binding to plasma proteins, where lead acetate caused the alteration in a high number of enzymes that distorted protein synthesis in hepatocytes.[24] However, a molecular work done also ascertained a decrease in serum aspartate transferase concentration and was attributed to a decrease in hepatic deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA) induced by lead intoxication or due to decreased utilization of free amino acids for protein synthesis.[25]

In group III (lead only), the histological evaluation (Figure 6) demonstrated vascular ulceration, vascular congestion, intense necrosis of major liver architecture, and periportal inflammation, further confirming the toxicological effect of lead on the liver. The above histological finding corroborated earlier work done by[26,27,28,29] on vascular congestion of the liver architecture[30] on necrosis of the liver architecture and on the vascular ulceration and periportal inflammation.[31]

Administration of 200mg of aqueous extract of L. inermis to the damage caused by lead on the liver showed a promising step by regeneration of hepatocytes by way of activating Kupffer cells with active vascular congestion and activation of hepatic cells as seen in Figure 10. Nevertheless, in advancing the study to a higher concentration of 400mg/kg body weight per day of aqueous extract of L. inermis, a greater amelioration of injury to hepatocytes was detected in protection against lead-induced liver damage. Meaning that the hepatic cells were completely normal, and liver-protecting Kupffer cells were almost activated. One could infer that the higher the dose, the better the desired positive outcome, as affirmed in this study.

On the contrary, evaluating the protective properties of aqueous extract of L. inermis by giving 400mg/kg of aqueous extract of L. inermis and thereafter inducing the injurious effect of 100mg/kg of lead acetate after 30 minutes was disastrous. This is to prove the fact that aqueous extract of L. inermis is useful in the treatment of already damaged liver cells rather than preventing. Clinically, this property of L.inermis could be taken into consideration in humans with similar liver lesions as confirmed histologically in this study: evidence-based anatomy.

By extension, a highly expensive drug called Silymarin, a known drug used in the treatment of liver disease with an undetected actual mechanism of action according to literature and web, showed the similar ameliorative effect of aqueous extract of L. inermis; the architecture of the liver was reverted to normal with the activation of Kupffer cells.[32] This attenuated effect was also in accordance with the same work done by dos Reis and colleagues.[32] That shows that Silymarin attenuates the adverse effects of damage to the liver, showing less extensive steatosis and necrosis.

Conclusion

Given the limitations and adverse effects of current chelation therapies for lead poisoning, the aqueous extract of Lawsonia inermis may serve as an alternative treatment, particularly in patients with lower blood lead levels where traditional chelation is deemed unnecessary and potentially harmful. The extract shows promise in protecting hepatic cells from toxicity caused by heavy metals, suggesting its use as a hepatoprotective agent, particularly in populations exposed to environmental toxins, such as lead. Findings also indicate that Lawsonia inermis may aid in hepatocyte regeneration and the activation of Kupffer cells, highlighting its potential in regenerative medicine or therapies aimed at restoring liver function post-toxicity. The presence of Silymarin and Lawsonia inermis suggests a possible synergistic effect, indicating that Lawsonia inermis could be used in conjunction with other hepatoprotective agents to enhance overall therapeutic efficacy. In populations at risk for heavy metal exposure, Lawsonia inermis may be considered for use as a dietary supplement to bolster liver health and mitigate toxicological impact.

Investigation into the specific molecular mechanisms through which Lawsonia inermis exerts its hepatoprotective effects, including pathways involved in lipid metabolism, liver regeneration, and oxidative stress reduction, should be carried out to further the potential of Lawsonia inermis.

References

- Chengaiah B, Rao K, Kumar K, Muthumanickam A, Madhusudhana C. Medicinal importance of natural dyes: a review. Int J PharmTech Res. 2010;2:1-10. Medicinal importance of natural dyes: a review

- Oladunmoye MK, Kehinde FY. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in treating viral infections among Yoruba tribe of South Western Nigeria. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2011;5(19):2991-3004. doi:10.5897/AJMR10.004 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Abdulfatai A, Oridupa O, Akorede J, et al. Safety evaluation of Lawsonia inermis on physiological, andrological and haematological parameters of male Wistar rats. J Basic Med Vet. 2022;11(2):75-89. doi:10.20473/jbmv.v11i2.32483 Crossref

- Seetharami Reddi V, J SJKR, T. Herbal remedies for hair disorders by the tribals of East Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh. J Exp Sci. 2011;2(8):1-5. Herbal remedies for hair disorders by the tribals of East Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh

- Ozaslan M, Zumrutdal ME, Daglioglu K, et al. Antitumoral effect of Lawsonia inermis in mice with EAC. Int J Pharmacol. 2009;5(4):263-267. doi:10.3923/ijp.2009.263.267 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Idowu O, Soniran O, Ajana O, Aworinde D. Ethnobotanical survey of antimalarial plants used in Ogun State, Southwest Nigeria. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol. 2010;4:55-60. Ethnobotanical survey of antimalarial plants used in Ogun State, Southwest Nigeria

- Aguwa C. Toxic effects of the methanolic extract of Lawsonia inermis roots. Pharm Biol. 2008;25(4):241-245. doi:10.3109/13880208709055201 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kumari P, Joshi G, Tewari L. Diversity and status of ethno-medicinal plants of Almora District in Uttarakhand, India. Int J Biodivers Conserv. 2011;3:1-10. Diversity and status of ethno-medicinal plants of Almora District in Uttarakhand, India

- Orwa C, Mutua A, Kindt R, Jamnadass R, Simons A. Agroforestree database: a tree reference and selection guide, version 4.0. World Agroforestry Centre ICRAF; 2009. Agroforestree Database: A Tree Reference and Selection Guide, version 4.0

- Sajadi SA, Alamolhoda AA, Hashemian SJ. Thermal behavior of alkaline lead acetate: a study of thermogravimetry and differential scanning calorimetry. Scientia Iranica. 2008;15:435-439. Thermal behavior of alkaline lead acetate: a study of thermogravimetry and differential scanning calorimetry

- Suleman M, Khan AA, Hussain Z, et al. Effect of lead acetate administered orally at different dosage levels in broiler chicks. Afr J Environ Sci Technol. 2011; 5:1017-1026. doi:10.5897/AJEST10.278 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Piro O, Baran E. Crystal chemistry of organic minerals – salts of organic acids: the synthetic approach. Crystallogr Rev. 2018;24(1):1-27. doi:10.1080/0889311X.2018.1445239 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kiernan J. Dyes and other colorants in microtechnique and biomedical research. Color Technol. 2006;122(1):1-21. doi:10.1111/j.1478-4408.2006.00009.x Crossref | Google Scholar

- Samanta A, Konar A. Dyeing of textiles with natural dyes. In: Natural Dyes: Advances in Textile Coloration and Finishing. 2011. doi:10.5772/21341 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Drury RA, Wallington EA. Carleton’s histological techniques. 5th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1980:195. Carleton’s histological techniques

- Orisakwe OE, Husaini DC, Afonne OJ. Testicular effects of sub-chronic administration of Hibiscus sabdariffa calyx aqueous extract in rats. Reprod Toxicol. 2004;18(2):295-298. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2003.11.001 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ibrahim NM, Eweis EA, El-Beltagi HS, Abdel-Mobdy YE. Effect of lead acetate toxicity on experimental male albino rat. Southeast Asian J Trop Biomed. 2012;2(1):41-46. doi:10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60187-1 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Upasani CD, Balaraman R. Effect of vitamin E, vitamin C, and spirulina on the levels of membrane-bound enzymes and lipids in some organs of rats exposed to lead. Indian J Pharmacol. 2001;33:185-191. Effect of vitamin E, vitamin C, and spirulina on the levels of membrane-bound enzymes and lipids in some organs of rats exposed to lead

- Orisakwe OE. Lead and cadmium in public health in Nigeria: physicians neglect and pitfall in patient management. North Am J Med Sci. 2014;6(2):61-70. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.127740 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Azoz HA, Raafat RM. Effect of lead toxicity on cytogenetics, biochemical constituents, and tissue residue with protective role of activated charcoal and casein in male rats. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2012;6:497-509. Effect of lead toxicity on cytogenetics, biochemical constituents, and tissue residue with protective role of activated charcoal and casein in male rat

- Ali ZY, Atia HA, Ibrahim NH. Possible hepatoprotective potential of Cynara scolymus, Cupressus sempervirens and Eugenia jambolana against paracetamol-induced liver injury: in-vitro and in-vivo evidence. Nat Sci. 2010;10:75-86. (PDF) Possible Hepatoprotective Potential of Cynara scolymus, Cupressus sempervirens and Eugenia jambolana Against Paracetamol-Induced liver Injury: In-vitro and In-vivo Evidence | Zeinab Yousef – Academia.edu

- Noriega GO, Tomaro ML, del Batlle AMC. Bilirubin is highly effective in preventing in vivo delta-aminolevulinic acid-induced oxidative cell damage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1638(2):173-178. doi:10.1016/s0925-4439(03)00081-4 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Abeed S, Aldujaily A, Hadee N, Ameer A. Hazardous effects of lead (Pb) on hematological and biochemical parameters in Awassi sheep grazing in the Najaf Center. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2019;10:1-6. doi:10.5958/0976-5506.2019.03136.X Crossref | Google Scholar

- Goering PL. Lead-protein interactions as a basis for lead toxicity. Neurotoxicology. 1993;14(2-3):45-60. Lead-protein interactions as a basis for lead toxicity

- Moussa S, Bashandy S. Biophysical and biochemical changes in the blood of rats exposed to lead toxicity. Biophysics. 2008;18:1-10. Biophysical and biochemical changes in the blood of rats exposed to lead toxicity

- Liu CM, Ma JQ, Sun YZ. Protective role of puerarin on lead-induced alterations of the hepatic glutathione antioxidant system and hyperlipidemia in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49(12):3119-3127. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2011.09.007 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Johar D, Roth JC, Bay GH, Walker JN, Kroczak TJ, Los M. Inflammatory response, reactive oxygen species, programmed (necrotic-like and apoptotic) cell death and cancer. Rocz Akad Med Bialymst. 2004; 49:31-39. Inflammatory response, reactive oxygen species, programmed (necrotic-like and apoptotic) cell death and cancer

- El-Sokkary GH, Abdel-Rahman GH, Kamel ES. Melatonin protects against lead-induced hepatic and renal toxicity in male rats. Toxicology. 2005;213(1-2):25-33. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2005.05.003 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sharma A, Sharma V, Kansal L. Amelioration of lead-induced hepatotoxicity by Allium sativum extracts in Swiss albino mice. Libyan J Med. 2010;5(1):4621. doi:10.3402/ljm.v5i0.4621 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Pandey G, Srivastava DN. A standard hepatotoxic model produced by paracetamol in rat. Toxicol Int. 2008;15:69-70. A standard hepatotoxic model produced by paracetamol in rat

- Suradkar SG, Vihol D, Patel J, Ghodasara DJ, Joshi B, Prajapati K. Patho-morphological changes in tissues of Wistar rats by exposure to lead acetate. Vet World. 2010;3:1-5. Patho-morphological changes in tissues of Wistar rats by exposure to lead acetate

- Lívero FA, Martins GG, Telles JEQ, et al. Hydroethanolic extract of Baccharis trimera ameliorates alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Chem Biol Interact. 2016;260:22-32. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2016.10.003 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not applicable

Funding

The author declares that no financial support or sponsorship was received from any commercial entities that could be perceived as influencing the study outcomes.

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Enoghase Raymond Joseph

Department of Anatomy

School of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Benin, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria

Email: enoghase41@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Osarinmwian Ilefeghian Brownson

Department of Anatomy

School of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Benin, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria

Osegbe Esemuede Deborah

Department of Medical Biochemistry

School of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Benin, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria

Abu Jamilah

Department of Biochemistry

Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Benin, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria

Abukadiri Mariam

Department of Industrial Chemistry

Faculty of Physical Sciences, University of Benin, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria

Ajufoh Chukwudi Zion

Department of Anatomy

School of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Benin, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the research ethical committee of the college of medical sciences, University of Benin.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors of this study declare that there was no conflict of interest regarding the publication or the conduct of this research. Furthermore, the authors affirm that there is no personal relationship or affiliation that could be construed as influencing the research conducted or the interpretation of its findings.

All data and results presented in this study were obtained through rigorous scientific methods and are discussed impartially. The authors remain committed to upholding the integrity of the research process and ensuring transparency in all aspects of the work. Any potential conflicts of interest that may arise in the future will be disclosed promptly in accordance with ethical guidelines.

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Enoghase R. J, Osarinmwian I. B, Osegbe E. D, Abu J, Abukadiri M, Ajufoh C. Z. Hepatoprotective Effects of Lawsonia inermis Aqueous Extract Against Lead Acetate-Induced Liver Injury in Wistar Rats. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622418. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622418 Crossref