Author Affiliations

Abstract

Motor neuron disease (MND) includes a heterogeneous clinical spectrum of conditions associated with dysfunction and degeneration of motor neurons. Deterioration of motor neurons will eventually lead to respiratory paralysis and pave the way to death. It was discovered that genetics plays a major role in the development of disease. The hard reality of this disease is that it has no remission, no stoppage, no slowing down, no cur,e and there are no survivors.

Keywords

Motor neuron disease, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Paraplegia, Frontotemporal dementia, Glassgow coma scale, Excitotoxicity, Bulbar paralysis, Superoxide dismutase, Organic psychosis.

Introduction

Motor neuron disease is the progressive deterioration of anterior horn cells of the spinal cord and corticospinal tracts, causing lower motor neuron lesions and upper motor lesion, respectively. In some cases, certain motor nuclei of the brainstem are also affected, which precipitates bulbar paralysis. Deterioration of motor neurons will cause muscle weakness, muscle wastage, loss of mobility in the limbs, and difficulty with speech, swallowing, and breathing.[1-4]

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is the one with the poorest diagnosis. ALS has a rapid skeletal muscle weakness that eventually leads to the need for ventilatory support or death due to respiratory failure.[1] Most ALS are idiopathic in nature, 5-10% are of familial form, which is in an autosomal dominant fashion.[2] Age distribution shows that the mean age of onset is mid 50’s, but it can be developed in adults of any age and has a direct correlation between the disease incidence and age advancement.[3] Incidence and prevalence of disease account for 2 per 100,000 and 6 per 100,000, respectively. Incidence of ALS is elevated in men, with a female ratio of 1.5:16.[2]

The etiology is not fully understood, but prominent theories concerning pathogenesis point to glutamate excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, microglial cell activation, apoptosis, and mitochondrial dysfunction.[4] About 20% of familial cases, mutations in superoxidase dismutase (SOD1) is identified whereas other rare type of congenital adult MND are Kennedy disease (X-linked recessive) and adult spinal muscular atrophy (autosomal recessive) characterized by lower motor dysfunction. Table 1 explains the genetic influence and the type of ALS involved.

|

ALS1 |

Mutation in SOD1 gene is a rare form of recessive juvenile onset with predominant upper motor neuron features. |

|

ALS8 |

A point mutation in the gene encoding vesicle associated protein B (VAPB) causes an autosomal dominant form of ALS. |

|

ALS4 |

Senataxin (SETX) mutation causing ALS4 may be more frequent and heterogeneous than expected. |

|

TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TARDBP) mutation in ALS |

Provided important clues to the possible pathogenic mechanisms involved in TDP-43 Proteinopathies. The elevated plasma levels of TDP-43 in some patients with neurodegenerative disease supports the possible use of TDP-43 as an in-vivo biomarker to facilitate in the diagnosis and monitoring the effects of therapy. |

|

ALS6 |

Mutation in the fused in sarcoma/translocated in liposarcoma (FUS/TLS), a gene that encodes a protein, similar function to TDP43 were found to cause ALS6 and further has a role in pathogenesis of ALS. |

|

Autosomal dominant ALS |

Mutation in Optinuerin, a protein which is encoded by OPTN gene, and vasolin containing protein gene were recently found to be linked to it. |

|

Autosomal recessive juvenile ALS |

SGP11 associated gene SPATACSIN |

|

X-linked juvenile and adult-onset ALS |

Ubiquilin 2 (UBQLN2) mutation |

| ALS with dementia and ALS linked to chromosome 9p21 |

Hexanucleotide repeat expansion in CRORF72 as the origin. |

Table 1: Genetic influence and the type of ALS involved

History:

ALS, otherwise known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, motor neuron disease, or Charcot disease, is an adult-onset progressive neurodegenerative disorder that involves large motor neurons of the brain and spinal cord.[2] It is usually presented with weakness and wasting of limbs and bulbar muscles, which causes respiratory failure within 5 years and ultimately leads to death. In 1874, French neurologist Jean Martin Charcot defined both clinical and pathological features of the disease and named it ALS. In 1880, Sir William Osler, a Canadian physician, came up with the hereditary component in the disease pathophysiology.[1] After a century later, the first gene linked to adult-onset autosomal dominant ALS, copper zinc SOD1, was identified, and that led to the transgenic animal model of the disease.[1] The mouse model became the backbone of ALS research and has been used worldwide to investigate the pathogenic mechanism and to test experimental therapies. In the post decade, the list of genes causing motor neuron disease grew significantly. SOD1 and C90RF72 are the most common genetic causes of ALS.[3]

Case Presentation

Presenting concerns & Clinical findings:

A 40-year-old female patient presented to the hospital with a history of insomnia for 4 days, decreased food intake for 2 days, and disoriented behavior. During the examination, the patient presented dysarthria, upper limb wastage, urinary incontinence, and muscle atrophy. Muscle stiffness is seen in the lower limbs. No cranial nerve deficits were observed except for tongue fasciculation. Additional symptoms were disorientated behavior.

Disease history:

In 1992, the patient suffered from a seizure episode (age of 15), no medication was taken continuously, and the seizure episode never occurred thereafter. At the age of 20, patients developed difficulty in walking, although leg movements were possible. Later on, muscle movements were restricted and undergone paraplegia condition, which led to muscle stiffness and upper limb wastage. She also exhibited frontotemporal dementia with familial ALS. In addition, urinary incontinence showed which was treated with pyridostigmine 60 mg once daily and baclofen 5 mg twice daily for muscle stiffness. From a functional point of view, the respiratory muscles were not involved; thus, tracheostomy or other invasive mechanical ventilation has not been provided to the patient so far.

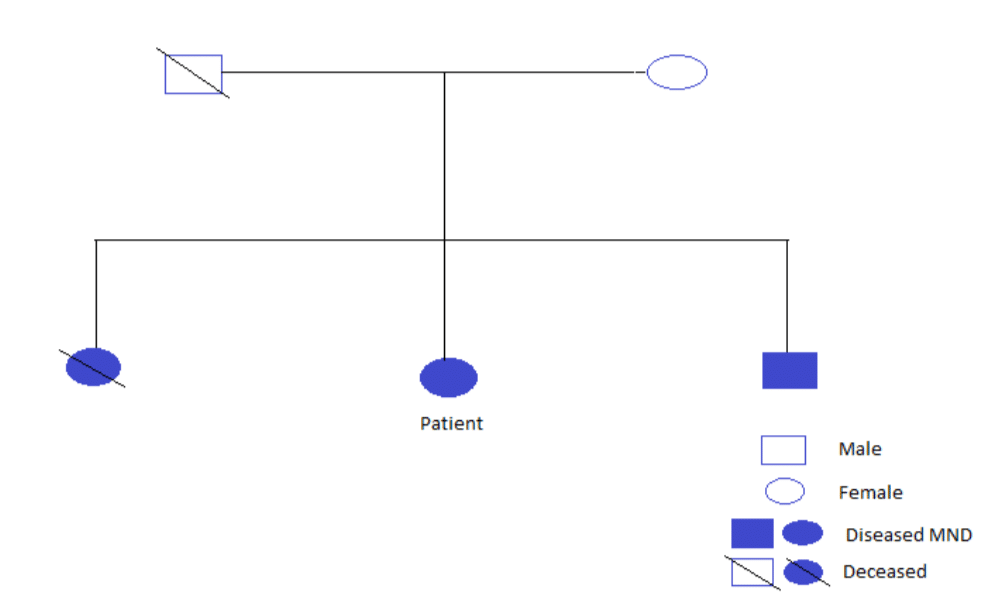

Family history:

The incidence of MND in her younger brother and elder sister was revealed, where the onset of disease above the age of 20 was displayed with reduced muscle coordination and slow progression of the disease. Elder sister had lower motor neuron clinical manifestations and died at the age of 46 because of respiratory muscle paralysis. The younger brother also showed lower motor neuron involvement with paraplegia as well. No other blood relatives had a history of MND or other neurodegenerative disorders.

Figure 1: Family history tree

Case Management

Diagnostic analysis and treatment objective:

Glassgow Coma Scale (GCS) has three components like eye, verbal, and motor responses. The summation score of eye, verbal, and motor responses provided an overall score of 14, which shows mild head injuries. The eye movement score 4 shows rapid movement, the verbal response score 4 reveals the confused state, and the motor response score 4 manifests the normal flexion. Ultrasound of the abdomen findings were normal appearance of the liver, gall bladder, pancreas, spleen, both kidneys, urinary bladder, and uterus, but exhibited a small ovarian cyst. The creatinine phosphokinase levels were 229 U/L (range: 24-190 U/L), which is of medical significance. Other blood parameters were hemoglobin 11.6 gm% (range: 12-14.5 gm%), serum creatinine 1 mg/dl (range: 0.6-1.6 mg/dL), blood urea 36 mg/dL (range: 10-40 mg/dL), erythrocyte sedimentation rate 58 mm/hr (range: less than 20 mm/hr), packed cell volume 35% (range: 37-45%).

The subjective and objective parameters made the assessment and diagnosis of familial ALS, along with frontotemporal dementia and organic psychosis. The goal of the therapy was to control disturbed behavior and to provide good sleep since she had Insomnia that persisted for 4 days, which impacted her quality of life. The treatment was initiated with olanzepine (2.5 mg) twice daily, sodium valproate (200 mg) & valproic acid (87 mg) combination once daily, zolpidem (10 mg) once daily, risperidone (1 mg) once daily on first day of admission and altered to 1 mg twice daily regimen, pyridostigmine (60 mg) was given for her urinary incontinence. The patient was pale and dull on arrival to the department, so the patient was initiated on infusion of 500 ml dextrose normal saline (5% & 0.9%). Following the therapy, the patient reported symptom relief and was discharged.

Discussion

Organic psychosis is characterized by abnormal brain function due to physical impairment or brain injury, which can cause hallucinations and delusions, often associated with psychotic disorders. The mental health of the patient is impaired due to the physical disability caused by the disease.[1]

In brief, the case presents the strong genetic influence of familial ALS together with frontotemporal dementia and organic psychosis.[3] The possible cause of drug-induced psychosis was evaluated prior to the diagnosis of organic psychosis. The siblings also had a similar onset of clinical manifestation and diagnosis above the age of 20 years, even though there is no significant past family history of motor neuron disorder or other neurodegenerative disorder. The elevated creatine phosphokinase level signifies muscular dystrophy. Ultrasound and hematological tests revealed normal renal function.[2] Dysarthria shows the preoccupation of muscles used for speech, which showcases the disease progression. The involvement of the pulmonary muscle is not prominent in disease development. The goal of the therapy was accomplished during the hospital stay, and the patient was discharged.[2]

MND has a strong correlation with the genetic influence. The possible causes of MND are excitotoxicity of glutamate, oxidative stress, and axonal injury. Free radical accumulation causes damage to motor neurons, which are responsible for the control of involuntary muscles. Deterioration of motor neurons limits the muscular activities, which manifest as muscle wastage and stiffness. Therefore, mild exercise is essential to minimize muscle wasting.[4]

Conclusion

MND is a clinical condition that progresses rapidly once it is diagnosed, and the survival rate is minimal. The early detection may help prevent disease advancement. MND is believed to have a strong relationship with genetic constituents. This case also depicts the strong association of MND with inheritance. More prompt measures and efforts need to be taken to understand the exact pathophysiology of the disease and to innovate in treating the disease, as the incidence of ALS is on the rise.

References

- Cifu D, Lew HL. Braddom’s Rehabilitation Care: A Clinical Handbook. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2025. Braddom’s Rehabilitation Care: A Clinical Handbook

- Rabinstein AA, Shulman LM. Acupuncture in clinical neurology. Neurologist. 2003;9(3):137-148. doi:10.1097/00127893-200305000-00002 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mangelsdorf I, Walach H, Mutter J. Healing of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A case report. Complement Med Res. 2017;24(3):175-181. doi:10.1159/000477397 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rison RA, Beydoun SR. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-motor neuron disease, monoclonal gammopathy, hyperparathyroidism, and B12 deficiency: Case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:298. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-4-298 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr. Manoj K, MBBS, MD, Psychiatrist, and Dr. Varghese Antony Pallan, MBBS, MD, DM (Neurology), Neurologist, for providing valuable support and necessary facilities.

Funding

Not reported

Author Information

Afra Mohamed

Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences

St. James’ Hospital Trust Pharmaceutical Research Centre (DSIR Recognised) Kerala, India

Email: aframohamed123@gmail.com

Author Contribution

The author contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles and involved in the writing – original draft preparation and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Afra M. Genetic Influence of Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Accompanying Frontotemporal Dementia And Organic Psychosis. medtigo J Neurol Psychiatry. 2024;1(1):e3084114. doi:10.63096/medtigo3084114 Crossref