Author Affiliations

Abstract

Gastric cancer remains a significant global health challenge, particularly pronounced among older adults but increasingly affecting younger populations. Diverse histological subtypes, primarily adenocarcinomas, further highlight the complexity of gastric cancer by presenting differently across age groups and ethnicities. Non-specific symptoms often hinder early detection, which is crucial for effective treatment. Advanced diagnostic tools and targeted screening programs, as demonstrated in countries like Japan and South Korea, can enhance early detection rates and improve outcomes. To effectively fight this cancer, we need a combination of public health programs, individualized preventative measures, and improvements in medical technology that can meet the specific needs of at-risk groups. This will help lower the global burden of gastric cancer. In this article, we showcase a case study of a 22-year-old woman who received a diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) caused gastric cancer, underscoring the importance of timely diagnosis and effective management.

Keywords

Gastric cancer, Helicobacter pylori, Laboratory tests, Proton pump inhibitor, Diagnosis, Computed tomography, Dietary and lifestyle changes.

Introduction

Gastric cancer, also known as stomach cancer, originates from uncontrolled cellular proliferation within the stomach, an organ centrally located in the upper abdomen just below the ribs. This malignancy can develop in any part of the stomach, though globally, it predominantly affects the stomach body. In contrast, in the United States of America (USA), it is more commonly diagnosed at the gastroesophageal junction, where the esophagus meets the stomach. The specific location of the cancer significantly influences treatment strategies, which may include surgical resection of the tumor, supplemented by preoperative and postoperative therapies. Early-stage gastric cancer, confined to the stomach, offers the best prognosis, with many cases being curable. However, most diagnoses occur at advanced stages when the cancer has breached the stomach wall or metastasized, significantly diminishing the likelihood of a cure [1,2].

The disease exhibits a higher incidence in Eastern Asia, Eastern Europe, and Central and South America, compared to Western countries. In the USA, certain racial and ethnic minorities-specifically Black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native communities-experience higher incidence and mortality rates. Men are nearly twice as likely to develop gastric cancer as women, with Black men facing particularly high mortality rates. Alarmingly, recent trends indicate an increase in gastric cancer among younger populations, including a notable rise among Hispanic women under 45 years old. These demographic shifts necessitate ongoing research into the unique clinical, biological, and prognostic characteristics of gastric cancer in these younger cohorts [3].

Risk factors such as infection with H. pylori, obesity, and gastroesophageal reflux disease, alongside genetic predispositions, significantly elevate the risk of developing gastric cancer. Diagnosis often involves a combination of endoscopic examination and imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT) scans and Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess the extent of disease spread, crucial for staging, which ranges from 0 to IV. Advanced stages are often identified by invasive procedures like laparoscopy when non-invasive methods are insufficient. Despite advancements in diagnostic modalities, the prognosis remains poor for advanced cases, highlighting the critical need for early detection and targeted treatment approaches [4,5].

H. pylori is a curved, gram-negative rod that infects the stomach. Presentation can range from asymptomatic to heartburn before or after a meal, depending on the site of infection, nausea, vomiting, weight gain, or weight loss. It is diagnosed by urea breath test, blood or stool tests, or upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy. In cases of long-term undiagnosed infection, it can lead to gastric cancer of the cardia. In this case, report we discuss gastric cancer in a 22-year-old Asian-American woman caused by H. Pylori, this case report warrants a diagnosis of H. Pylori infection earlier, leading to effective treatment and prognosis.

Case Presentation

A 22-year-old Asian American woman presented to the outpatient clinic with a six-month history of severe nausea, vomiting, and heartburn, coupled with a significant weight loss from 65 kilograms to 55 kilograms, with no history of fever. She reported no use of tobacco, alcohol, or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) but had been taking over-the-counter medicines to manage her symptoms. Her diet frequently included canned foods, and she had no familial history of diabetes, hypertension, gastric cancer, rectal cancer, or H. pylori infection. Her parents migrated to the USA when she was two years old.

Initially, she was prescribed a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and histamine H2-receptor antagonists (H2 blockers) and advised to avoid trigger foods containing spices and sugars, and undergo a stool test for H. pylori, and an abdominal ultrasound was also recommended. The patient’s H. Pylori test returned positive, with an abdominal ultrasound showing a gastric ulcer in the fundal area. However, a week later her condition worsened, leading to her presentation at the emergency department with blood in her vomitus and severe heartburn. On admission, her vitals were pulse 102 beats/minute, respiratory rate of 16 breaths/minute, blood pressure of 100/60 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation of 97% on room air. Blood tests were ordered, and complete blood count (CBC) showed a hemoglobin level of 7.6 mg/dL, indicating severe anemia. Electrolytes and tumor markers were within normal limits, except for a low hemoglobin count (Table 1).

| Test Name | Patient Value | Normal Range |

| Hemoglobin (mg/dL) | 7.6 | 12.0 – 15.5 |

| Mean Corpuscular Volume (fL) | 68 | 80-100 |

| White Blood Cell Count (WBC) | 9.5 | 4.5 – 11.0 x109/L |

| Platelet Count | 193 | 150 – 450 x109/L |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 139 | 135 – 145 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.0 | 3.5 – 5.0 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 110 | 95 – 108 |

| C-reactive Protein (CRP) (mg/L) | Normal | Varies by lab |

| Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) (mm/hr) | Normal | 15-20 for men

20-30 for women |

Table 1: Laboratory tests and results

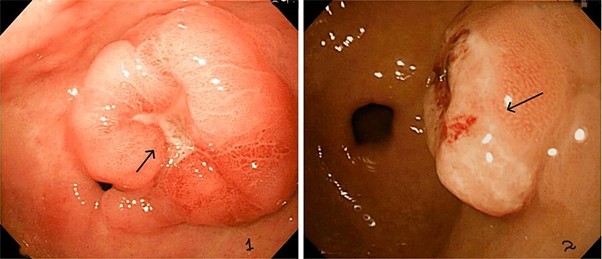

Consequently, chest and abdominal X-rays were ordered showing no signs of perforation and she was referred for an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) that identified a lesion with 10 cm submucosal lesion with central ulceration and irregular margins and borders opposite the lesser curvature of the stomach, extending into the duodenum, suspecting gastric cancer (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Ulcerated lesion in Fundus on EGD

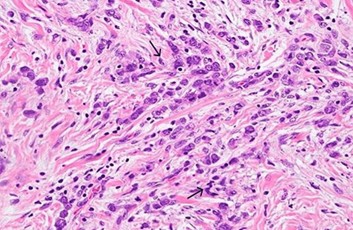

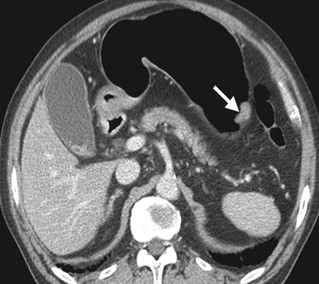

She underwent a CT scan (Figure 2) abdomen with IV contrast and Positive emission tomography (PET) scan, which confirmed the absence of metastasis. The biopsy results confirmed grade III gastric adenocarcinoma with gastric dysplasia, anaplasia, increased nucleus to cytoplasm ratio, and other features of cancer, associated with H. pylori infection (Figure 3). She promptly started on antibiotics for H. pylori and underwent partial gastrectomy, including adjacent lymph nodes. Post-surgery, her management was continued by the Oncology department.

Figure 2: Grade III lesions on gastric biopsy showing dysplasia, increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio

Figure 3: Abdominal CT scan showing gastric cancer

Case Management

The patient initiated a triple therapy regimen, consisting of Esomeprazole, Clarithromycin, and Amoxicillin, taken twice daily. Commence with transparent fluids and gradually transition to easily digestible foods as tolerated. Encourage sufficient fluid consumption, but caution patients against consuming excessive amounts of fluid while eating. Regularly observe for any deficiencies in nutrition and make necessary modifications to the supplements. Arrange regular appointments for weight monitoring, blood analysis, and comprehensive health assessments. Highlight the significance of consuming well-balanced and nourishing meals while refraining from high-sugar or high-fat foods. Regular follow-up and adaptation of dietary and lifestyle changes are crucial for optimal recovery and long-term health.

Discussion

Gastric cancer, also known as stomach cancer, manifests through uncontrolled cell growth originating from the stomach’s lining. This malignancy is notably prevalent among older adults, typically affecting individuals over the age of 50. However, recent trends indicate a concerning rise in gastric cancer incidence among younger populations, including a notable prevalence within Asian American communities. This demographic shift highlights the necessity of exploring specific genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors contributing to the disease in diverse populations [4,5].

Adenocarcinomas, accounting for about 90% of gastric cancer cases, originate from the glandular epithelium of the stomach mucosa. There are two main histological subtypes of gastric adenocarcinoma: the intestinal type, which is more common in older adults and resembles intestinal tissue, and the diffuse type, which is prevalent among younger patients and characterized by poorly differentiated cells that infiltrate the gastric wall. This histological diversity underscores the variability in how the disease presents and progresses in different age groups and ethnic backgrounds.

In terms of geographic distribution, gastric cancer is most prevalent in East Asia, Eastern Europe, and Central and South America, with comparatively lower rates in the United States and other Western countries. Within the U.S., the disease disproportionately affects black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native populations compared to their white counterparts. Men are particularly vulnerable, with nearly double the incidence rate of women, while black men face almost double the mortality rate compared to white men. These disparities emphasize the importance of tailored healthcare strategies to effectively address and manage gastric cancer within specific racial and ethnic groups [6,7,8].

The diagnosis of gastric cancer in younger individuals, including Asian Americans, poses unique challenges due to the often subtle and misleading symptoms that can mimic less severe gastrointestinal disorders. Typically, we employ early diagnostic techniques such as upper endoscopy and biopsy only after symptoms have escalated. Advanced diagnostic tools such as enhanced endoscopic ultrasound, serum biomarkers, and molecular profiling offer the potential for earlier detection. Moreover, countries with high incidence rates, such as Japan and South Korea, have successfully implemented national screening programs that have significantly improved early detection and survival rates through public health initiatives and regular screening [6].

Conclusively, the increasing incidence of gastric cancer among young Asian Americans calls for an integrated approach combining advanced diagnostic techniques, targeted preventive measures, and public health strategies tailored to specific at-risk populations. With the right combination of early detection, personalized treatment plans, and comprehensive education and awareness campaigns, it is possible to significantly improve outcomes for individuals affected by this challenging disease [8,9].

Conclusion

In conclusion, gastric cancer remains a significant global health challenge, particularly pronounced among older adults but increasingly affecting younger populations. Geographically, the disease’s prevalence varies; it is particularly common in Japan, China, and South Korea due to the use of canned foods. Diverse histological subtypes, primarily adenocarcinomas, further highlight the complexity of gastric cancer by presenting differently across age groups and ethnicities. Non-specific symptoms often hinder early detection, which is crucial for effective treatment. Advanced diagnostic tools and targeted screening programs, as demonstrated in countries like Japan and South Korea, can enhance early detection rates and improve outcomes. To effectively fight this cancer, we need a combination of public health programs, individualized preventative measures, and improvements in medical technology that can meet the specific needs of at-risk groups. This will help lower the global burden of gastric cancer.

References

- Suryawala K, Soliman D, Mutyala M, et al. Gastric cancer in women: A regional health-center seven-year retrospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(25):7805-7813. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i25.7805

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Alhalabi MM, Alsayd SA, Albattah ME. Advanced diffuse gastric adenocarcinoma in a young Syrian woman: A case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;78:103728. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103728 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mangaza A, Josué BM, Gloire B, et al. Gastric cancer in young adults: Case series of three cases. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2023;110:108758. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2023.108758 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Yan L, Chen Y, Chen F, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on gastric cancer prevention: Updated report from a randomized controlled trial with 26.5 years of follow-up. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(1):154-162.e3. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.039 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wroblewski LE, Peek RM Jr, Wilson KT. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: Factors that modulate disease risk. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(4):713-739. doi:10.1128/CMR.00011-10 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ishaq S, Nunn L. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: A state-of-the-art review. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2015;8(Suppl 1):S6-S14. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: a state of the art review PubMed | Google Scholar

- Helicobacter pylori and stomach cancer. WebMD. Accessed March 10, 2025. Helicobacter pylori and stomach cancer

- Underferth D. H. pylori and your stomach cancer risk. MD Anderson Cancer Center. Published April 23, 2021. Accessed March 10, 2025. H. pylori and your stomach cancer risk

- Cleveland Clinic. Stomach cancer. Accessed March 10, 2025. Stomach cancer

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

Not reported

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

FNU Saveeta

Department of Internal Medicine

St. John’s Hospital, 800 E Carpenter St, Springfield, Illinois 62769, United States

Email: saveetasahtiya@gmail.com

Co-Author:

Dalvinder Singh

Department of Internal Medicine

St. John’s Hospital, 800 E Carpenter St, Springfield, Illinois 62769, United States

Email: dalvindersandhu5@gmail.com

Gurjot Singh

Department of Internal Medicine

St. John’s Hospital, 800 E Carpenter St, Springfield, Illinois 62769, United States

Email: gurjot.js.25@gmail.com

FNU Payal

Department of Internal Medicine

St. John’s Hospital, 800 E Carpenter St, Springfield, Illinois 62769, United States

Email: payalpritwani15@gmail.com

Shubam Trehan

Department of Internal Medicine

St. John’s Hospital, 800 E Carpenter St, Springfield, Illinois 62769, United States

Email: shubamtrehan@gmail.com

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Informed Consent

Not applicable as not reported

Conflict of Interest Statement

None

Guarantor

Not applicable

DOI

Cite this Article

Saveeta F, Dalvinder S, Gurjot S, Payal F, Shubam T. Gastric Cancer in a 22-Year-Old Woman. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(3):e3062233. doi: 10.63096/medtigo3062233 Crossref