Author Affiliations

Abstract

This review addresses current and future therapeutic approaches to Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a disorder of cognitive deterioration that degenerates over time, as well as memory malfunction. In line with this, the review investigates disease-modifying drugs, which include anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies and tau protein modulation. Neuroinflammation also includes complement system inhibitors and controls microglial activation. Besides this, it talks about synaptic plasticity improvement. In addition, it discusses the inhibitors, namely beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) and p38 alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38α MAPK), that contrast with the traditional treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists that are critical in the management of AD. This review also includes the new drug delivery systems: nanoparticles and intranasal delivery systems that may potentially enhance therapeutic effectiveness toward the targeting of the brain. Of these, gene therapy and ribonucleic acid (RNA)-based approaches such as clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) can be used to slow the disease through targeting at a genetic level. Lifestyle and dietary interventions, including physical activity and specific nutrient supplementation, serve to include management of AD symptoms. It is underpinned that the treatment of AD would be multiple in nature, including pharmacological intervention and lifestyle changes for better patient outcomes and reduced progression of the disease.

Keywords

Alzheimer’s disease, Tau protein, Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor, Anti-amyloid, Monoclonal antibodies.

Introduction

AD is an advancing neurodegenerative disease that mainly affects geriatrics. Pathologically, AD is characterized by the presence of amyloid β (Aβ) and phosphorylated tau, neuroinflammation, and synaptic dysfunction.[1] Most common risk factors of AD include older age (generally, greater than 65 years of age) and being a carrier of the apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele (APOE ε4 allele). Being a progressive disease, it is marked by a slow decline in cognitive, behavioral, and physical functions. Many therapeutic approaches have been tried, but historically, the AD can be treated primarily by aiming at symptomatic treatment and not actual curative treatment.[2] One of the techniques that has been used in the past is the inhibitors of γ-secretase and β-secretase. Currently, the approved treatments by food and drug administration (FDA) include five drugs like tacrine, rivastigmine, donepezil, galantamine are cholinesterase inhibitors, and memantine which is a NMDA receptor blocker.[3] Another method is disease modification therapies (DMTs) which are aimed at altering the underlying pathology of AD. Currently, monoclonal antibodies, which remove Aβ plaques, are being used for early-stage AD. Tau targeting therapies and Neuroinflammation targeting drugs are also being developed under DMTs.[4] Another emerging tool for the cure of AD is ASOs and CRISPR technology.[5]

Figure 1: Various therapeutic targets in AD

Treatment

1. DMT for AD

- Anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies: The amyloid hypothesis of AD states that the accumulation of the amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptides results in neurofibrillary tangles, neuroinflammation, cell death, and neurotransmitter deficiencies.[6] Two amyloid-targeting monoclonal antibodies (MABs), aducanumab (Aduhelm®) and lecanemab (Leqembi®), have recently been licensed in the United States to treat AD.[7] Aducanumab and lecanemab bind to soluble beta-amyloid protofibrils, which disrupt synaptic function. They coat the amyloid protofibrils and make them appear as foreign substances. These coated amyloid protofibrils attract microglia, which are the brain’s resident immune cells. These cells recognize antibody-tagged amyloid, which results in phagocytosis and reduces the amyloid plaque burden.[8]

- Tau protein modulation: Tau is a microtubule-associated protein (MAP); hence, it helps regulate the microtubule assembly and maintain their structural stability. Aβ peptide in AD disrupts the balance of activities of different protein kinases such as cyclin-dependent protein kinase 5 (CDK5), glycogen-synthase kinase-3ß (GSK3ß), MAPK, cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), calcium-calmodulin-dependent kinase-II (CaMK II), and phosphatases such as protein phosphatase 2 (PP2A) and microtubule affinity-regulating kinase (MARK), which results in perturbation of cellular signalling. This imbalance results in microtubule disassembly. Free tau molecules form paired helical filaments.[9] Semorinemab, a completely humanized monoclonal antibody with an immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) isotype backbone, attaches to the N-terminal domain (amino acid residues 6-23) of tau, and it has been shown to bind all types of tau that are full-length, including phosphorylated and aggregated tau.[10]

2. Neuroinflammation and immune modulation

- Complement system inhibitors: One of the components of the innate immunity system is the “Complement System” that ensures the possibility to eliminate pathogens and damaged cells, but its overactivation in the brain leads to neurodegeneration and worsens the symptoms and progression of AD. Out of the three pathways of the complement system, the classical pathway is particularly implicated in AD, which is triggered by amyloid-beta plaques and contributes to chronic neuroinflammation and synaptic dysfunction.[11] In AD, complement component 1q (C1q), which is a key protein of the classical pathway, binds to the synapses in the brain, marking them for destruction. This synaptic tagging via C1q triggers the activation of the downstream pathway of C3 and other proteins of the complement system; subsequently, microglia, the immune cells in the brain, eliminate or prune the synapses.[12] ANX005 inhibits C1q, thus preventing the activation of the antibody-dependent pathway. It therefore prevents the tagging and destruction of synapses, thereby preserving synapses with subsequent loss of neurons and effects on cognitive decline that are associated with AD.[13]

- Targeting neuroinflammation: Colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) is one of the receptor tyrosine kinases present on the surface of microglia that react with ligands such as colony stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) and interleukin 34 (IL-34), which is crucial for microglial development. An inhibitor of CSF1R, namely pexidartinib, prevents the downstream signaling to microglia activation and proliferation. Consequently, its use results in decreased counts of the cells that are activated in the brain, thus preventing the adverse neurotoxic consequences of overactivated microglia. Activated microglia have been demonstrated to release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α IL-1β reactive oxygen species (ROS), and other mediators, which augment neuroinflammation. Pexidartinib reduces the expression of these mediators, which are associated with chronic inflammation related to neurodegenerative mechanisms in AD.[14] The selective pharmacological adenosine triphosphate (ATP) competitive inhibitor GW2580 of CSF1R also contributes to a significant reduction in the proliferation of microglia, neuroinflammation, and disease pathology in AD.[15]

3. Synaptic plasticity and neuroprotection

- BACE1 inhibitors: BACE1 is a membrane-spanning aspartyl protease that can cleave APP present at the beta site. The breakdown of amyloid precursor protein (APP) by BACE1 and gamma-secretase results in the formation of amyloid-b peptides, among which Aβ40 and Aβ42 have the potential to aggregate and contribute to the amyloid plaque accumulation in affected brains of AD. The amyloid-b accumulation in the brain causes neuroinflammation, synaptic malfunction, and neuronal death, issues which collectively lead to cognitive loss noticed in the pathology of AD.[16] A brain penetrable inhibitor of BACE1 activity, atabecestat, that reduces cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ was designed as an oral therapy for AD, which blocks the initial step of APP cleavage, thus preventing the formation of amyloid -b peptide.[17] Another BACE-1 inhibitor is verubecestat, which reduces the level of Aβ by the same mechanism as Atabecestat.[18]

- Role of neuroprotective agents: Chronic neuroinflammation is one of the important elements in the progression of AD because proinflammatory cytokines released excessively from glial cells, namely microglia and astrocytes, lead to neuronal damage, followed by microglial activation, and hence provoking more changes that result in progressive nerve cell loss. MAPK p38α modulates the innate immunological response. AD has been observed with greater stimulation of the p38α MAPK pathway, and this increased inflammation and pathophysiology offer considerable promise for the drug target in the progress of new therapies.[19] Neflamapimod (previously known as VX-745) is an ATP-competitive inhibitor of p38α kinase. In vitro, it inhibits p38α, reducing beta amyloid/tau toxicity and neuro-inflammation.[20]

4. Cholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA receptor antagonists

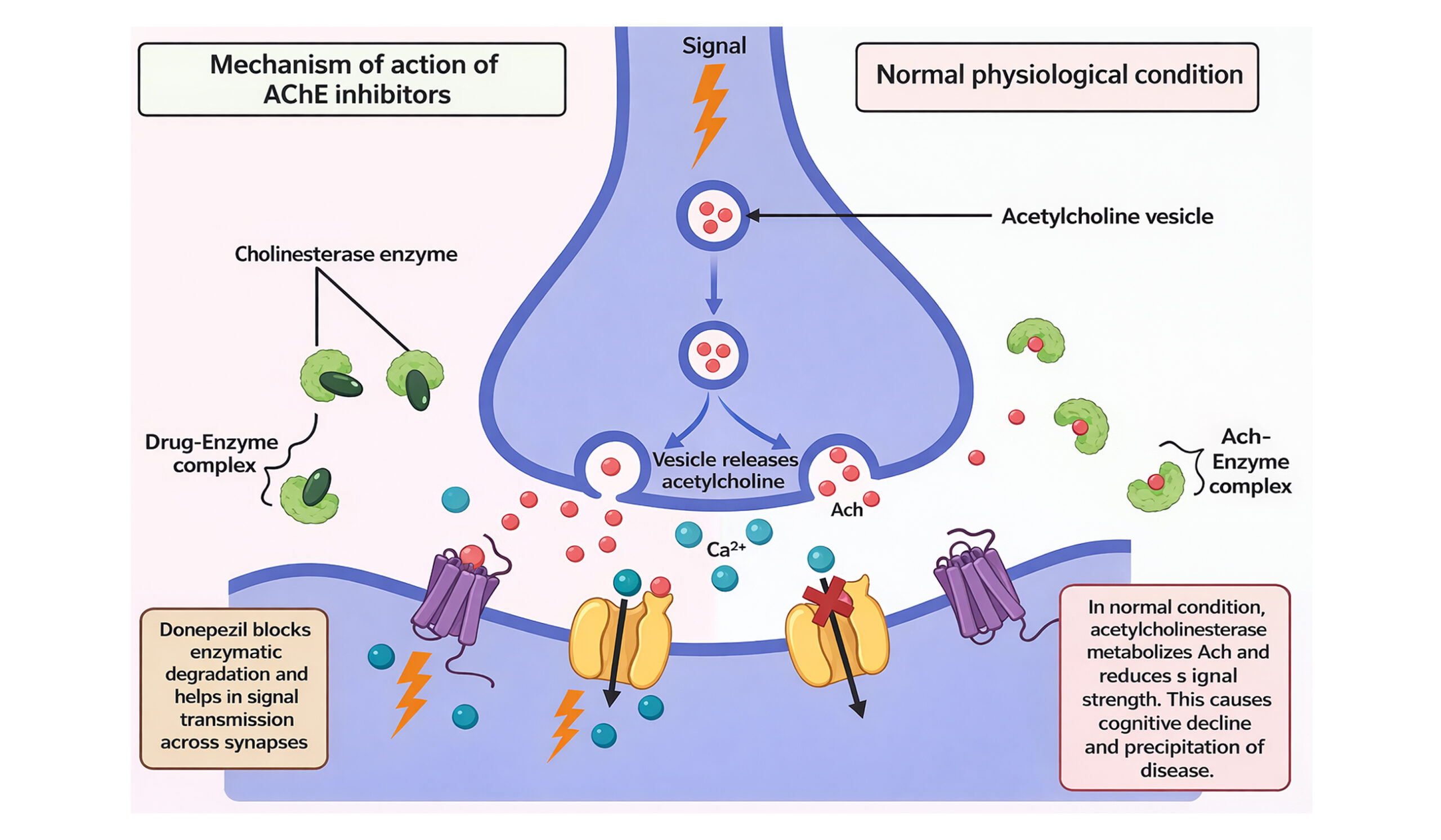

- Role of cholinesterase inhibitors: The ‘amyloid hypothesis’ proposes that acetylcholinesterase (AChE) facilitates beta-amyloid accumulation in the brain as senile plaques or neurofibrillary tangles of affected persons. The deposition of beta-amyloid is believed to have an important role in the initiation and progression of AD. Butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) is an enzyme closely associated with AChE. It acts as a co-regulator of cholinergic neurotransmission by breaking down AChE. Early senile plaque formation is associated with elevated activity of BuChE, which is a major contributor to Ab-aggregation. Therefore, it has been established that AChE and BChE inhibition are essential targets for the efficient treatment of AD.[21] Tacrine, velnacrine, metrifonate, and physostigmine were the acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEI) that belonged to the first generation. The most popular AChEI in the second generation, along with galantamine, rivastigmine, and donepezil, is donepezil. Donepezil becomes the cornerstone of AD therapies because of issues with first-generation pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. These AChEI increase levels of acetylcholine in the brain, a neurotransmitter essential for memory and learning.[22,23]

Figure 2: An enzyme AChE present at the synapse that breaks down acetylcholine and thus reduces the strength of the signal. AChE inhibitor drugs prevent the pathway because it leads to reversible binding to the enzyme and thus facilitate the signal transmission across the synapse

- Role of NMDA receptor antagonists: NMDA receptors are glutamate receptors that play an essential role in synaptic plasticity, memory, and learning. The overexpression of glutamate floods the NMDA receptors with more Ca2+, therefore causing excitotoxicity that overactivates the NMDA receptors. Such cases lead to oxidative stress, cell death, and damage to neurons in the course of AD.[24] Memantine is an uncompetitive antagonist of NMDA receptors characterized by a high voltage dependency and very rapid kinetics of unblocking. The former property will bestow memantine with its unique ability to allow the transmission of very strong transitory physiological signals against the pathological influx of Ca2+ and oxidative stress in the postsynaptic neuron.[25]

- Mitochondrial Function and Oxidative stress: Mitochondria are associated with the metabolism of energy in cells and directly affect the functioning and survival of neurons. Impairment of mitochondria results in reduced ATP production, increased ROS production, subsequent oxidative stress, neuronal death, and progressive cognitive decline.[26] Elamipretide is a selective cardiolipin inhibitor, a specific lipid found in the inner mitochondrial membrane, necessary for structural and functional mitochondrial maintenance. It binds cardiolipin, decreases mitochondrial ROS, and inhibits mitochondrial swelling, which triggers a decline in the release of cytochrome c due to its high Ca2+ overload.[27]

5. Innovative delivery systems

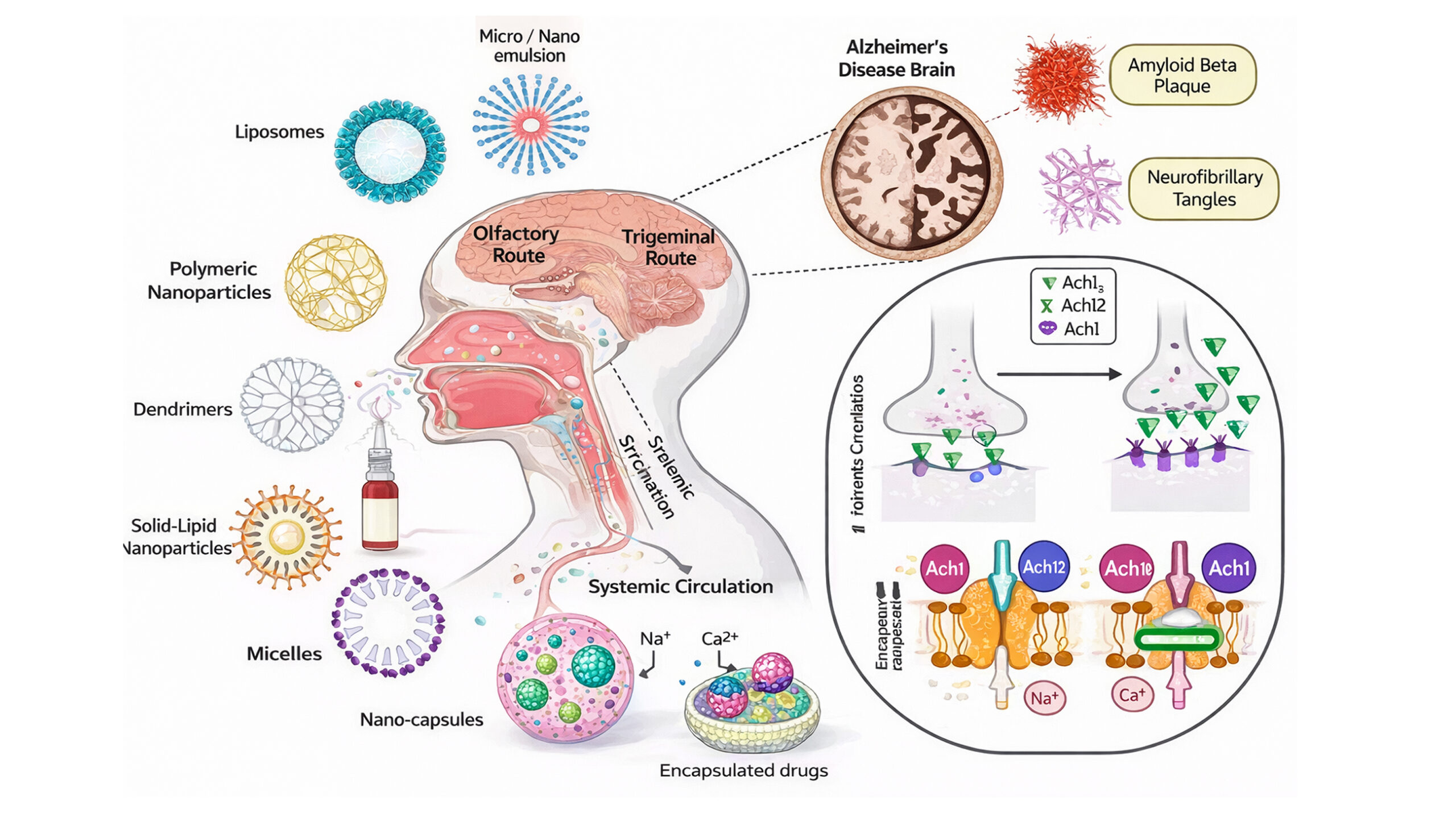

- Nanoparticle drug delivery: Brain diseases are difficult to treat because of some limitations, such as the extremely selective permeability of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and the ionic charge of the extracellular matrix of the brain with nanopores. Neurodegenerative diseases such as AD can be treated by a prospective drug delivery revolution offered by nanomedical applications. The unique physiochemical properties and small size of nanoparticles allow them to easily cross the BBB, delivering effective therapeutic concentrations of drug to the brain, bypassing the metabolism in the liver and spleen.[28]

- Intranasal delivery: Through the olfactory and trigeminal pathways, a direct route for the delivery of drugs from the nasal cavity was discovered. Strong vascularization of the nasal mucosa promotes quick medication absorption and allows for better brain targeting, which may result in a decrease in the dose of the therapeutic agent. Therefore, intranasal administration appears to be an appropriate route of administration for several therapeutic drugs, including those used to cure AD.[29]

Figure 3: Various nanocarriers used to treat AD with their mechanism

6. Gene therapy and RNA-based approaches

CRISPR is a gene-modifying tool that is a great hope for AD research and treatment. There are also several known strong risk genes, among these APOE, most importantly with the APOE4 allele, and presenilin 1 (PSEN1), presenilin 2 (PSEN2), with APP also being linked. CRISPR allows editing or correction of these genes in cells or animal models in a way that creates an avenue toward various therapeutic interventions.[30] ASOs are small strands of nucleic acids designed to seek out RNA molecules, thereby inhibiting the production of proteins involved in diseases. In this case, ASOs could be designed to target the gene encoding amyloid precursor protein, which later gets cleaved by proteolytic activity to produce Aβ. The presence of amyloid plaques in the brain marks the occurrence of AD. Reducing levels of APP will also reduce levels of the toxic Abo peptide and should therefore correlate with a reduction of progression rate of the disease.[31]

Conclusion

In conclusion, with disease-modifying therapies such as aducanumab and lecanemab, along with new approaches to tau protein, neuroinflammation, and synaptic plasticity, the landscapes of AD keep changing. The older treatments-cholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA antagonists, are irreplaceable, but one major intervention is being provided in the form of novel gene therapy, antisense oligonucleotides, and advanced drug delivery systems. Thus, the integrated approach towards slowing disease progression and improving outcomes is offered with a combination of the given therapies and lifestyle modifications.

References

- Scheltens P, De Strooper B, Kivipelto M, et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2021;397(10284):1577-1590. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32205-4 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Passeri E, Elkhoury K, Morsink M, et al. Alzheimer’s disease: Treatment strategies and their limitations. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(22):13954. doi:10.3390/ijms232213954 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Birks JS, Chong LY, Grimley Evans J. Rivastigmine for Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9(9):CD001191. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001191.pub4 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Suzuki K, Iwata A, Iwatsubo T. The past, present, and future of disease-modifying therapies for Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2017;93(10):757-771. doi:10.2183/pjab.93.048 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Athar T, Al Balushi K, Khan SA. Recent advances on drug development and emerging therapeutic agents for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Biol Rep. 2021;48(7):5629-5645. doi:10.1007/s11033-021-06512-9 PubMed | Crossref |

Google Scholar - Van Dyck CH. Anti-amyloid-β monoclonal antibodies for Alzheimer’s disease: Pitfalls and promise. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;83(4):311-319. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.08.010 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cummings J. Anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies are transformative treatments that redefine Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics. Drugs. 2023;83(7):569-576. doi:10.1007/s40265-023-01858-9 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Perneczky R, Dom G, Chan A, Falkai P, Bassetti C. Anti-amyloid antibody treatments for Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2024;31(2):e16049. doi:10.1111/ene.16049 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Medeiros R, Baglietto-Vargas D, Laferla FM. The role of tau in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2011;17(5):514-524. doi:10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00177.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ramakrishnan V, Bender B, Langenhorst J, et al. Semorinemab pharmacokinetics and the effect on plasma total tau pharmacodynamics in clinical studies. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2024;11(5):1241-1250. doi:10.14283/jpad.2024.146 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Carpanini SM, Torvell M, Morgan BP. Therapeutic inhibition of the complement system in diseases of the central nervous system. Front Immunol. 2019;10:362. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00362 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Nimmo J, Byrne RAJ, Daskoulidou N, et al. The complement system in neurodegenerative diseases. Clin Sci. 2024;138(6):387-412. doi:10.1042/CS20230513 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Morgan BP. Complement in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Semin Immunopathol. 2018;40(1):113-124. doi:10.1007/s00281-017-0662-9 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Han J, Chitu V, Stanley ER, Wszolek ZK, Karrenbauer VD, Harris RA. Inhibition of colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R) as a potential therapeutic strategy for neurodegenerative diseases: opportunities and challenges. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022;79(4):219. doi:10.1007/s00018-022-04225-1 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Neal ML, Fleming SM, Budge KM, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of CSF1R by GW2580 reduces microglial proliferation and is protective against neuroinflammation and dopaminergic neurodegeneration. FASEB J. 2020;34(1):1679-1694. doi:10.1096/fj.201900567RR Crossref | Google Scholar

- Coimbra JRM, Marques DFF, Baptista SJ, et al. Highlights in BACE1 inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Front Chem. 2018;6:178. doi:10.3389/fchem.2018.00178 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Novak G, Streffer JR, Timmers M, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of atabecestat (JNJ-54861911), an oral BACE1 inhibitor, in early Alzheimer’s disease spectrum patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study and a two-period extension study. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12(1):58. doi:10.1186/s13195-020-00614-5 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Egan MF, Kost J, Voss T, et al. Randomized trial of verubecestat for prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(15):1408-1420. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1812840 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Detka J, Płachtij N, Strzelec M, Manik A, Sałat K. p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase—An emerging drug target for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Molecules. 2024;29(18):4354. doi:10.3390/molecules29184354 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sharma A, Mehra V, Kumar V, Prakash H. Tailoring MAPK pathways: New therapeutic avenues for managing Alzheimer’s diseases. Preprints. 2023;2023121509. doi:10.20944/preprints202312.1509.v1 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Anand P, Singh B. A review on cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Pharm Res. 2013;36(4):375-399. doi:10.1007/s12272-013-0036-3 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cacabelos R. Donepezil in Alzheimer’s disease: From conventional trials to pharmacogenetics. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(3):303-333. PubMed

- Singh B, Day CM, Abdella S, Garg S. Alzheimer’s disease current therapies, novel drug delivery systems and future directions for better disease management. J Control Release. 2024;367:402-424. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2024.01.047 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rogawski MA, Wenk GL. The neuropharmacological basis for the use of memantine in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drug Rev. 2003;9(3):275-308. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2003.tb00254.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Danysz W, Parsons CG. Alzheimer’s disease, β-amyloid, glutamate, NMDA receptors and memantine – Searching for the connections. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167(2):324-352. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02057.x PubMed | Crossref |

Google Scholar - Nhu NT, Xiao SY, Liu Y, Kumar VB, Cui ZY, Lee SD. Neuroprotective effects of a small mitochondrially-targeted tetrapeptide elamipretide in neurodegeneration. Front Integr Neurosci. 2022;15:747901. doi:10.3389/fnint.2021.747901 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Zhao W, Xu Z, Cao J, et al. Elamipretide (SS-31) improves mitochondrial dysfunction, synaptic and memory impairment induced by lipopolysaccharide in mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16(1):230. doi:10.1186/s12974-019-1627-9 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kassem LM, Ibrahim NA, Farhana SA. Nanoparticle therapy is a promising approach in the management and prevention of many diseases: Does it help in curing Alzheimer’s disease? J Nanotechnol. 2020:1-8. doi:10.1155/2020/8147080 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Dighe S, Jog S, Momin M, Sawarkar S, Omri A. Intranasal drug delivery by nanotechnology: Advances in and challenges for Alzheimer’s disease management. Pharmaceutics. 2023;16(1):58. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics16010058 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lu L, Yu X, Cai Y, Sun M, Yang H. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:803894. doi:10.3389/fnins.2021.803894 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Thirumalai S, Patani R, Hung C. Therapeutic potential of APP antisense oligonucleotides for Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndrome-related Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegeneration. 2024;19(57). doi:10.1186/s13024-024-00745-5 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

Not reported

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Maida Noor

Department of Pharmacy

Quaid-I-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan

Email: assetocorsa123@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Mamoona Khalid, Syed Muhammad Talha, Ayesha Tehreem, Anum Bibi

Department of Pharmacy

Quaid-I-Azam University, Pakistan

Rehan Amjad

Department of Pharmacy

University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Not reported

Guarantor

Not reported

DOI

Cite this Article

Maida N, Mamoona K, Syed MT, Ayesha T, Anum B, Rehan A. Exploring Current and Emerging Therapeutic Approaches in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Comprehensive Review. medtigo J Neurol Psychiatry. 2024;1(1):e3084113. doi:10.63096/medtigo3084113 Crossref