Author Affiliations

Abstract

Background: Acute abdominal pain (AAP) is a significant clinical issue globally, contributing to approximately 7-10% of emergency room (ER) visits. Its broad differential diagnoses, including conditions like appendicitis and bowel obstructions, require rapid and accurate diagnosis for effective management. In Pakistan, the healthcare system, especially in tertiary care hospitals, faces challenges such as limited access to advanced diagnostic tools and specialized professionals, which complicates the management of AAP. This study aims to describe the clinical presentation of AAP in a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan, providing data to inform clinical practice and policy development.

Methodology: This cross-sectional study was conducted in the ER of Fazaia Ruth Pfau Medical College Hospital (FRPMCH), Pakistan. Ethical approval was obtained from the Fazaia Ruth Pfau Medical College (FRPMC) ethical review board. Data collection spanned from March to June, focusing on patients aged 18 and above presenting with AAP. Exclusion criteria included patients with chronic abdominal pain, recent surgery, pregnancy, and those unable to consent. A total of 144 patients were recruited using consecutive sampling. Data was collected through face-to-face interviews using a standardized questionnaire in english and urdu. The clinical examination was performed by the attending duty medical officer. Data analysis involved descriptive and inferential statistics using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Statistics version 26.0.

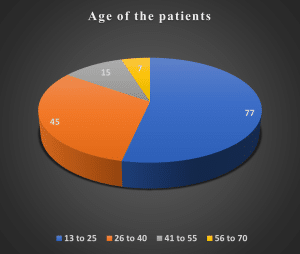

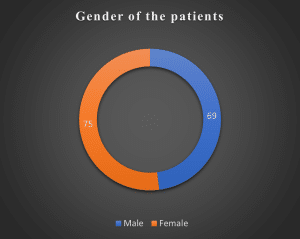

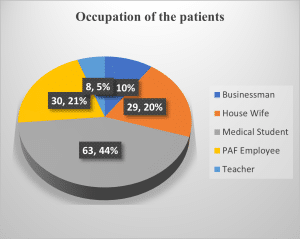

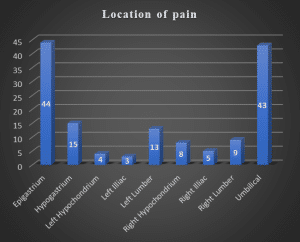

Results: The study included 144 participants, with a balanced gender distribution (47.6% male, 51.7% female). The majority were aged 13-25 years (53.1%), with medical students (43.4%) and personnel action form (PAF) employees (20.7%) being the most common occupations. Gradual onset of pain was reported in 57.2% of cases, and pain duration varied, with 37.9% experiencing symptoms for more than five days. The pain was primarily located in the epigastric (30.3%) and umbilical (29.7%) regions. Non-radiating pain was reported by 73.8%, and 69% rated their pain as severe. Significant correlations were found between pain characteristics and demographic factors, such as age and gender, with older patients experiencing longer pain durations and females reporting more localized pain.

Conclusion: This study provides valuable insights into the clinical presentation of AAP in a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan, emphasizing the need for effective pain management strategies, comprehensive triage systems, and continuous education for healthcare providers. These measures are essential to improve the diagnosis, treatment, and overall management of AAP in emergency settings, enhancing patient care and outcomes in Pakistan’s healthcare system.

Keywords

Acute abdominal pain, Emergency room, Gastrointestinal symptoms, Tertiary care hospitals, Clinical presentation.

Introduction

AAP is a prevalent and pressing clinical issue worldwide, accounting for a substantial proportion of ER visits. It serves as a common presentation that encompasses a diverse spectrum of underlying conditions, ranging from benign to life-threatening.[1] This complexity poses a significant challenge in emergency medicine, necessitating prompt and accurate diagnosis to effectively manage the condition. Globally, AAP contributes approximately 7% to 10% of all ER visits, underscoring its critical nature in healthcare systems.[2] AAP presents a formidable challenge due to its broad differential diagnoses. Conditions such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, and bowel obstructions are among the many potential causes, each requiring a unique diagnostic and therapeutic approach.[3] The clinical complexity of these cases often demands rapid decision-making, a process complicated by nonspecific symptoms and the variable availability of diagnostic resources.[4]

The ability to accurately diagnose and manage AAP is vital for optimizing patient outcomes and reducing morbidity and mortality rates. However, in Pakistan, the healthcare infrastructure faces considerable challenges, particularly in accessing advanced diagnostic tools and specialized healthcare professionals. Tertiary care hospitals, serving as major referral centers, play a pivotal role in managing acute medical conditions, including AAP. In these settings, up to 25% of patients may remain undiagnosed with non-specific causes, particularly in rural areas where clinical resources are limited.[5] This underscores the need for a comprehensive understanding of the clinical presentation and diagnostic challenges associated with AAP in Pakistan’s diverse healthcare landscape.

The clinical presentation of AAP is highly variable, necessitating a thorough and systematic approach to evaluation in the ER. Patients may present with a wide array of symptoms, ranging from mild discomfort to severe pain, often accompanied by other symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, or fever. The differential diagnosis is extensive, encompassing both common and rare conditions, which requires clinicians to maintain a high index of suspicion and thorough evaluation.[6] This variability highlights the need for epidemiological and clinical profiling to better understand the distribution and presentation patterns of AAP.[7]

The initial assessment of AAP typically includes clinical evaluation, laboratory tests, and imaging studies. However, in resource-limited settings like Pakistan, the availability and utilization of these diagnostic tools are often constrained, complicating the diagnostic process. [8] Additionally, atypical presentations, particularly in vulnerable populations such as the elderly, can obscure the underlying pathology, making accurate diagnosis even more challenging.[9] Conditions like appendicitis and non-specific abdominal pain are frequent among ER presentations, necessitating careful differential diagnosis and management.[10] A timely and accurate diagnosis of AAP is crucial for improving patient outcomes. Delayed diagnosis can lead to severe complications, including infection, perforation, and sepsis, significantly increasing morbidity and mortality.[11] Therefore, comprehensive clinical evaluation remains a cornerstone in the initial assessment and management of these patients, ensuring that appropriate interventions are implemented promptly.

Previous studies have identified various diagnostic and management challenges associated with AAP, particularly in resource-limited settings. However, there is a notable paucity of localized data from Pakistan, limiting the applicability of findings from other regions to this context. This study aims to bridge this gap by providing specific insights into the presentations of AAP in a Pakistani tertiary care setting. The primary objective of this study is to describe the clinical presentation of AAP in the ER of a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan, providing valuable data to inform clinical practice and policy development. The findings from this study will offer critical insights into the management of AAP in emergency settings in Pakistan.

Methodology

Study design and participants:

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the ER of FRPMCH, a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan. The study commenced following ethical approval from the FRPMC ethical review board (FRPMC-IRB-2024-58). The research adhered to ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki of the world medical association (WMA). The consent part consisted of a debriefing statement on Google forms to display transparency and communication. All measures taken regarding privacy and confidentiality were explained to them. How the participant had a legal right to withdraw from the study at any given time with no penalty involved was also explained. In respect of safeguarding participant data security, all precautions were undertaken to maintain confidentiality.

Data security measures were rigorously implemented to safeguard participant information. To ensure the privacy and confidentiality of participants, all data collected was de-identified and stored securely. Personal information such as names, contact details, or other identifiers was not linked to the collected data. Only the research team had access to the data, and any published results or reports would not contain any information that could identify individual participants. The data was stored on secure servers and password-protected computers.

The data collection spanned from March to June. The study focused on evaluating the clinical presentation of patients presenting with AAP in the ER. Participants included patients of all genders aged 18 years and above who presented to the ER with AAP during the study period. The inclusion criteria were as follows: patients with a chief complaint of abdominal pain lasting less than a week, those willing to participate and provide informed consent, and those whose pain was of new-onset and severe enough to warrant ER evaluation. Exclusion criteria were set to ensure the accuracy and relevance of the data collected. Patients with a known diagnosis of chronic abdominal pain, those with a history of recent abdominal surgery (within the past month), pregnant women, and patients unable to provide informed consent due to altered mental status or language barriers other than english and urdu were excluded. Additionally, patients with trauma-related abdominal pain or those referred from other healthcare facilities for specific conditions were also excluded. These exclusions were implemented to focus the study on the acute presentations and to avoid confounding factors.

The world health organization (WHO) sample size calculator 2.0 was used to determine the minimum sample size needed, with a 95% confidence interval and a 5% margin of error, considering a rough estimate of AAP after studying several studies at 8.2%.[12] The calculation yielded a target sample size of approximately 114 patients. However, a total of 144 patients who met the criteria were recruited. Participants were recruited consecutively as they presented to the ER. Upon presentation, eligible patients were approached by primary and secondary research investigators who explained the study’s purpose, procedures, and the voluntary nature of participation. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before any data collection. Face-to-face interviews were carried out by trained interviewers, using a standardized questionnaire provided in both English and Urdu to cater to language preferences. The clinical examination was conducted by the attending duty medical officer.

Measures:

The study utilized a structured survey form to comprehensively collect data on patients presenting with AAP in the ER of a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan. The survey was meticulously divided into three key sections, each targeting specific aspects crucial for understanding the clinical presentation and associated factors of AAP.

Section 1: Demographic Profile focused on gathering basic information about the participants. This included categorization of age into groups, as well as recording the gender and occupation of the participants. This provided a broad overview of the patient demographics.

Section 2: Characteristics of AAP captured detailed information about the nature of the abdominal pain experienced by the patients. It recorded the duration of pain, specifying the onset, and noted whether the onset was gradual or sudden. The duration of symptoms was also documented. The survey further detailed the specific location of the pain (such as epigastrium, hypogastrium, left hypochondrium, among others) and whether the pain was radiating or not. Additionally, the continuity of pain was identified as either come & go or constant, and the association of pain with movement was noted, indicating if the pain increased with movement. The character of the pain was described using terms like cramping, dull, referred, sharp, and stabbing. Finally, the intensity of pain was rated on a scale of 1 to 10 (10 being the highest).

Section 3: Associated History of AAP collected information on the patient’s medical history and background factors that might influence their presentation and diagnosis. This included recording any gastrointestinal symptoms, changes in bowel movements, and whether the patient had a fever associated with abdominal pain. The survey also inquired about current medication use, any history of trauma, recent dietary changes, and the presence of food or medical allergies. It further explored whether the patient had previously experienced similar abdominal pain and if the pain was being managed with medication. Additionally, a detailed account of pre-existing medical conditions was collected, covering a range of conditions such as cholecystitis, constipation, GERD, hepatitis (A and E), hiatal hernia, inguinal hernia, irritable bowel syndrome, peptic ulcer disease, polycystic ovary syndrome, renal colic, and urinary tract infection.

This structured and detailed survey form facilitated a comprehensive assessment of each patient’s clinical presentation, ensuring that all relevant factors were considered in the diagnosis and management of AAP. The data collected provided a valuable foundation for analyzing the clinical profiles and potential underlying causes of AAP in this specific patient population.

Data analysis:

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The data analysis for the study “Evaluating Clinical Presentation of AAP in the ER: A Cross-Sectional Study” was conducted in several stages to ensure a thorough understanding of the clinical presentations and the relationships between demographic variables and pain characteristics.

Descriptive statistics:

Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize and present the results. Categorical items related to the sociodemographic profile of the participants were reported as counts with percentages. This included variables such as age, gender, and occupation. Additionally, descriptive statistics were calculated for the characteristics of AAP, including onset, duration, location, radiation, character, and severity of pain. This analysis helped to summarize the central tendencies and dispersions of these clinical characteristics, providing a comprehensive overview of the AAP presentations among the study participants.

Inferential statistics:

Non-parametric tests have been used to evaluate associations of demographic variables with various AAP characteristics. Since scores may not be distributed normally, the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis test were appropriate here. The Mann-Whitney U test was used in this study to establish differences between two independent groups, like gender, on AAP pain characteristics. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare differences among more than two independent groups with respect to these pain characteristics, such as age groups or occupation, in the present study. This approach can point toward any significant association between demographic factors and the clinical presentation of pain, thus suggesting some demographic influences on symptomatology.

Correlation analysis:

Kendall’s tau_b and Spearman correlation coefficients were utilized in the research to investigate relationships between pain characteristics and related factors such as gastrointestinal symptoms, active medication use, history of trauma, and recent changes in diet. The choice of Kendall’s tau_b and Spearman correlation was determined by the nature of the data, including ordinal and non-parametric variables. Statistical methods have therefore been used to identify key associations. P-values were used to indicate the strength and direction of correlation.

Visualization:

The demographic factors are represented graphically through the pie charts, and characteristics of pain are reflected through the bar graphs. This representation, both visually and graphically, further helped in clarifying patterns and frequencies of clinical presentations in this population.

For all statistical analyses, A significance level of 0.05 was set for all statistical tests, with a further distinction made at the 0.001 level for highly significant findings. Any p-values below this threshold were considered statistically significant. This comprehensive data analysis approach ensured a robust understanding of the clinical presentations of AAP and the associated demographic influences in the ER setting.

Results

Demographic profile:

The study included 144 participants presenting with AAP in the ER (refer to Table 1). The majority were aged 13 to 25 years (53.1%), followed by 26 to 40 years (31%), indicating a predominantly younger patient population. Gender distribution was relatively balanced, with 47.6% male and 51.7% female participants. The most common occupations among the respondents were medical students (43.4%) and PAF employees (20.7%), suggesting a significant representation from the healthcare and military sectors.

| Frequency | Percentage | |

| Age | ||

| 13 to 25 | 77 | 53.1 |

| 26 to 40 | 45 | 31 |

| 41 to 55 | 15 | 10.3 |

| 56 to 70 | 7 | 4.8 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 69 | 47.6 |

| Female | 75 | 51.7 |

| Occupation | ||

| Businessman | 14 | 9.7 |

| House Wife | 29 | 20 |

| Medical Student | 63 | 43.4 |

| PAF Employee | 30 | 20.7 |

| Teacher | 8 | 5.5 |

Table 1: Demographic profile

Characteristics of AAP:

Table 2 illustrates the characteristics of AAP. The onset of abdominal pain was reported as gradual in 57.2% of cases, with 42.1% experiencing a sudden onset. The duration of pain varied, with 37.9% experiencing symptoms for more than five days, and 24.8% for four days. Most patients (75.9%) reported symptoms persisting for less than a month, indicating the acute nature of the condition.

The pain was predominantly located in the epigastric (30.3%) and umbilical (29.7%) regions. Notably, 73.8% of patients reported non-radiating pain, with 25.5% experiencing radiation. The pain character varied, with cramping (48.3%), dull (16.6%), sharp (15.9%), and stabbing (11.7%) sensations being the most described. Regarding pain severity, 69% rated their pain as severe, while 30.3% considered it moderate.

| Frequency | Percentage | |

| Duration of pain (when did it start?) | ||

| 1 day ago | 15 | 10.3 |

| 2 days ago | 18 | 12.4 |

| 3 days ago | 20 | 13.8 |

| 4 days ago | 36 | 24.8 |

| 5 days ago | 55 | 37.9 |

| Onset of pain | ||

| Gradual | 83 | 57.2 |

| Sudden | 61 | 42.1 |

| Duration of symptoms | ||

| From 1 month | 110 | 75.9 |

| From 1 year | 3 | 2.1 |

| From 2 months | 15 | 10.3 |

| From 2 years | 3 | 2.1 |

| From 5 months | 13 | 9 |

| Location of pain | ||

| Epigastrium | 44 | 30.3 |

| Hypogastrium | 15 | 10.3 |

| Left hypochondrium | 4 | 2.8 |

| Left illiac | 3 | 2.1 |

| Left lumber | 13 | 9 |

| Right hypochondrium | 8 | 5.5 |

| Right illiac | 5 | 3.4 |

| Right lumber | 9 | 6.2 |

| Umbilical | 43 | 29.7 |

| Radiation of pain | ||

| Radiating pain | 37 | 25.5 |

| Not radiating | 107 | 73.8 |

| Continuity of pain | ||

| Come & go | 109 | 75.2 |

| Constant | 35 | 24.1 |

| Association with movement | ||

| Increased by movement | 74 | 51 |

| Not increased by movement | 70 | 48.3 |

| Character | ||

| Cramping | 70 | 48.3 |

| Dull | 24 | 16.6 |

| Referred | 10 | 6.9 |

| Sharp | 23 | 15.9 |

| Stabbing | 17 | 11.7 |

| Level and scale of pain | ||

| Low | 0 | 0 |

| Moderate | 44 | 30.3 |

| Severe | 100 | 69 |

Table 2: Characteristics of AAP

Associated symptoms and medical history:

Table 3 illustrates details of associated symptoms and medical history. Other gastrointestinal symptoms, like nausea and vomiting, were present in 51% of patients, with 69.7% reporting changes in bowel movements. Fever was associated with abdominal pain in 36.6% of cases. In terms of medical history, 33.8% of the participants reported no pre-existing medical conditions. However, among those with medical histories, constipation (17.9%), GERD (8.3%), and urinary tract infections (9%) were notable conditions.

| Frequency | Percentage | |

| Any gastrointestinal symptoms | ||

| Yes | 74 | 51 |

| No | 70 | 48.3 |

| Change in bowel movement | ||

| Yes | 101 | 69.7 |

| No | 43 | 29.7 |

| Fever associated with abdominal pain | ||

| Yes | 53 | 36.6 |

| No | 91 | 62.8 |

| Current medication use | ||

| Yes | 52 | 35.9 |

| No | 92 | 63.4 |

| History of trauma | ||

| Yes | 4 | 2.8 |

| No | 140 | 96.6 |

| Recent dietary changes | ||

| Yes | 87 | 60 |

| No | 57 | 39.3 |

| Food and medical allergies | ||

| Yes | 15 | 10.3 |

| No | 129 | 89 |

| Experience of similar abdominal pain | ||

| Yes | 108 | 74.5 |

| No | 36 | 24.9 |

| Is pain being managed by medication? | ||

| Yes | 104 | 71.7 |

| No | 40 | 27.6 |

| Pre-existing medical conditions | ||

| No pre-existing medical condition | 49 | 33.8 |

| Cholecystitis | 2 | 1.4 |

| Constipation | 26 | 17.9 |

| Food poisoning and diarrhea | 7 | 4.8 |

| Gall stones | 2 | 1.4 |

| Gerd | 12 | 8.3 |

| Hepatitis A | 2 | 1.4 |

| Hepatitis E | 1 | 0.7 |

| Hiatal hernia | 2 | 1.4 |

| Inguinal hernia | 2 | 1.4 |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 1 | 0.7 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 13 | 9 |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 2 | 1.4 |

| Renal colic | 10 | 6.9 |

| Urinary tract infection | 13 | 9 |

Table 3: Associated history of AAP

Lifestyle factors and pain management:

Table 3 illustrates details of lifestyle factors and pain management. Recent dietary changes were reported by 60% of patients, potentially implicating dietary factors in the onset of symptoms. A significant number of patients (74.5%) had experienced similar abdominal pain previously. The majority (71.7%) were managing their pain with medication, highlighting the importance of pharmacological intervention in this cohort.

Association of AAP presentation across demographics:

Table 4 shows significant associations between several variables. Duration of pain was significantly associated with age (p=0.016) and occupation (p=0.001), while location of pain showed a significant relation with age (p=0.034), gender (p=0.001), and occupation (p<0.001). The radiation of pain was significantly related to gender (p=0.01).

| Duration of pain (when did it start?) | Age | Gender | Occupation |

| Chi-Square test Sig (p-value) | 0.016 | 0.668 | 0.001 |

| Onset of pain | |||

| Chi-Square test Sig (p-value) | 0.107 | 0.678 | 0.364 |

| Duration of symptoms | |||

| Chi-Square test Sig (p-value) | 0.096 | 0.561 | 0.025 |

| Location of pain | |||

| Chi-Square test Sig (p-value) | 0.034 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Radiation of pain | |||

| Chi-Square test Sig (p-value) | 0.064 | 0.01 | 0.148 |

| Continuity of pain | |||

| Chi-Square test Sig (p-value) | 0.015 | 0.042 | 0.107 |

| Association with movement | |||

| Chi-Square test Sig (p-value) | 0.05 | 0.237 | 0.203 |

| Character | |||

| Chi-Square test Sig (p-value) | 0.018 | 0.068 | 0.015 |

| Level and scale of pain | |||

| Chi-Square test Sig (p-value) | 0.3 | 0.895 | 0.368 |

Table 4: Association of AAP presentation across demographic profile

Correlation analysis of AAP characteristics:

In this study, significant correlations were identified among various pain characteristics (refer to Table 5). The analysis revealed several significant relationships. A strong positive correlation was observed between the continuity of pain and the onset of pain (r = 0.399, p < 0.001), suggesting that patients with continuous pain were more likely to report a sudden onset. Additionally, the level and scale of pain showed a significant positive correlation with both constant pain and the onset of pain (r = 0.314, p < 0.001) and a strong negative correlation with the radiation of pain (r = -0.266, p < 0.001). This indicates that higher pain levels are associated with sudden onset and constant, radiating pain.

| I | II | III | IV | V | V1 | VII | |

| Duration of pain (when did it start?) | 1 | 0.145 | -0.024 | -0.035 | 0.044 | -0.225 | 0.157 |

| Onset of pain (Sudden) | 1 | -0.069 | -.203* | .399** | 0.122 | .314** | |

| Duration of symptoms | 1 | -0.055 | 0.01 | .179* | 0.068 | ||

| Radiation of pain (Non-radiating) | 1 | -0.111 | -0.032 | -.266** | |||

| Continuity of pain (Constant) | 1 | -0.065 | .323** | ||||

| Association with movement (Not associated) | 1 | -0.033 | |||||

| Level and scale of pain | 1 | ||||||

| ** Correlation Coefficient is significant at the 0.001 level (2-tailed) | |||||||

| * Correlation Coefficient is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed) | |||||||

Table 5: Correlation analysis of pain characteristics

In this study, various factors related to the clinical presentation of AAP were analyzed for their correlation with the associated history of the patient (see Table 6). Notably, the analysis revealed a significant positive correlation between radiation of pain (non-radiating) and the presence of other gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (r = 0.256, p < 0.001), as well as fever associated with abdominal pain (r = 0.259, p < 0.001). These findings suggest that non-radiating pain is more commonly associated with other GI symptoms and fever, which may indicate specific diagnostic considerations.

A significant negative correlation was found between current medication use and duration of symptoms (r = -0.395, p < 0.001), indicating that patients on current medication tend to report a shorter duration of symptoms. Additionally, current medication use was negatively correlated with continuity of pain (r = -0.248, p < 0.001) and association with movement (r = -0.368, p < 0.001), suggesting that medication may help alleviate continuous pain and pain associated with movement. Furthermore, past experience of similar abdominal pain was positively correlated with the duration of symptoms (r = 0.174, p < 0.05) and association with movement (r = 0.276, p < 0.05), suggesting that previous experiences may contribute to a prolonged perception of symptoms and an increased sensitivity to movement.

| Duration of Pain (when did it start?) | Onset of Pain (Sudden) | Duration of Symptoms | Radiation of Pain (Not Radiating) | Continuity of Pain (Constant) | Association with Movement (Not Associated) | Level and scale of pain | |

| Other GI symptoms | 0.077 | -0.067 | 0.044 | .256** | -0.046 | -.171* | -0.233 |

| Change in bowel movement | 0.038 | -0.055 | -0.155 | 0.137 | -0.09 | -0.094 | -0.037 |

| Fever associated with abdominal pain | -0.065 | -0.113 | 0.08 | .259** | -0.03 | -0.124 | -0.259 |

| Current medication use | 0.1 | -0.028 | -.395** | 0.054 | -.248** | -.368** | -0.143 |

| History of trauma | 0.012 | 0.026 | 0.105 | 0.003 | -0.096 | 0.005 | 0.101 |

| Recent dietary changes | -0.112 | 0.028 | 0.062 | 0.135 | 0.073 | .231** | -0.005 |

| Food and medical allergies | 0.108 | -0.108 | 0.097 | -0.164 | 0.019 | 0.032 | 0.169 |

| Experience of similar abdominal pain | -.158* | 0.061 | .174* | -0.02 | -0.034 | .276** | -0.054 |

| Is pain being managed by medication? | -.193* | 0.002 | .252** | -0.061 | 0.082 | .234** | -0.071 |

| ** Correlation is significant at the 0.001 level (2-tailed). | |||||||

| *Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). | |||||||

Table 6: Correlation analysis of pain characteristics against associated patient history

Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate the clinical presentation of AAP in the ER of a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan, focusing on the correlation between pain characteristics and associated patient history. Our findings provide valuable insights into the diagnostic considerations and management strategies for patients presenting with AAP. A notable portion of patients experienced a sudden onset, with pain localized to the epigastric and umbilical (29.7%) regions, which are indicative of gastrointestinal pathologies such as gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, or appendicitis. The predominance of non-radiating pain (73.8%) further suggests that localized intra-abdominal pathology is common among this patient cohort. Pain descriptions varied significantly. However, the severity of pain, with 69% of patients rating their pain as severe, emphasizes the urgent nature of these presentations and the critical need for prompt and effective pain management strategies in the emergency setting. These findings highlight the necessity for a comprehensive triage system to quickly identify and prioritize patients with potentially life-threatening conditions. Moreover, the study underscores the importance of a systematic diagnostic approach that considers common gastrointestinal conditions while remaining vigilant for more severe causes. The significant variation in pain characteristics and severity calls for tailored pain management protocols and emphasizes the need for emergency medicine personnel to be well-versed in the broad differential diagnoses of AAP. This study reinforces the importance of continuous education and training for healthcare providers to enhance patient outcomes and ensure timely and appropriate care.

The significant association between the duration of pain and age (p=0.016) suggests that older patients may experience longer durations of abdominal pain before seeking medical attention. Older adults may have different attitudes toward health and medical care. They might consider pain as an inevitable part of aging and therefore, may not seek medical help promptly. There may also be a fear of diagnosis, hospitalization, or invasive treatments, leading to a reluctance to consult healthcare providers. Studies have shown that older patients often delay seeking care for acute symptoms due to these concerns.[13,14]

Understanding this relationship is crucial for emergency medicine practitioners to ensure timely and appropriate interventions, particularly in older populations where the risk of complications may be higher. Additionally, the American Academy of Family Physicians has highlighted that AAP in older adults is frequently more severe and associated with higher risks of complications, underlining the importance of timely medical evaluation.[15]

The study also revealed significant gender-related differences in the location (p=0.001) and radiation (p=0.01) of pain. These differences may reflect biological, hormonal, or psychosocial factors influencing pain perception and reporting. For instance, females might report abdominal pain more frequently due to conditions like gynecological disorders, while males might underreport pain or present with different symptoms due to cultural norms or perceived expectations of toughness.

In our context, gender differences significantly influence the location and radiation of pain, particularly in abdominal and visceral contexts. For instance, studies on axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) show that women experience more widespread axial and peripheral pain compared to men, with specific areas like the thoracic region being more affected in women.[16] Additionally, hormonal factors contribute to these differences, as seen in studies examining visceral pain sensitivity in conditions like irritable bowel syndrome, where women are often more sensitive to pain stimuli, possibly due to hormonal influences.[17] Recognizing these differences is vital for accurate diagnosis and treatment, as misinterpretation of symptoms based on gender can lead to misdiagnosis or delayed care.

The study’s findings highlight a notable association between non-radiating abdominal pain and the presence of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and fever among patients presenting to the ER. This observation is crucial for clinicians as it aids in narrowing down differential diagnoses and optimizing management strategies for AAP, a common yet complex presentation in emergency settings.

The association between non-radiating abdominal pain and GI symptoms such as diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and fever in patients presenting to the ER has been explored in several studies. One study on the use of point-of-care ultrasound for assessing appendicitis noted that patients often present with abdominal pain without accompanying fever or other systemic symptoms, which can complicate diagnosis.[18] In contrast, a study on COVID-19 patients found that GI symptoms at initial presentation, including abdominal pain, were prevalent and linked to better outcomes, such as reduced mortality rates, compared to non-GI symptoms.[19] Furthermore, the role of ultrasound showed that non-radiating abdominal pain often correlates with serious conditions like appendicitis or intussusception, which require urgent intervention.[20] Overall, these studies suggest that while non-radiating abdominal pain with GI symptoms may sometimes lead to severe conditions, they are not always associated with poor outcomes, especially in COVID-19 patients.

The finding that 74.5% of patients presenting with AAP had experienced similar pain episodes previously is a critical observation with several implications for clinical practice and patient management in the ER setting. This high recurrence rate underscores the importance of thorough medical histories and comprehensive evaluations to identify underlying chronic or recurrent conditions contributing to these presentations. One possible interpretation of this finding is that many patients may suffer from chronic gastrointestinal disorders, such as peptic ulcer disease, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), or chronic gastritis, which often manifest with recurrent abdominal pain.

Recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) in adults is a significant health issue, with studies indicating a substantial prevalence. A large-scale survey in the United States revealed that 81.0% of respondents reported experiencing abdominal pain within the past week, with 61.5% of these individuals seeking medical care for their symptoms.[21] This high prevalence underscores the considerable burden of RAP on healthcare systems and the affected individuals’ quality of life. The prevalence of recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) in adults is a significant clinical concern, with studies indicating various underlying causes and characteristics. One of the studies highlighted that meal-related abdominal pain is common and often linked to disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBI), exacerbating both gastrointestinal (GI) and non-GI symptoms, including psychological distress.[22]

One study reported that a significant number of adults experience RAP, often linked to conditions such as abdominal epilepsy, where episodes of pain can mimic gastrointestinal disorders but are neurological in origin.[23] Additionally, chronic abdominal wall pain (CAWP) is another prevalent form of RAP, characterized by localized pain due to nerve entrapment or previous surgeries. This condition is often misdiagnosed as visceral pain, leading to extensive and sometimes unnecessary diagnostic procedures.[24] The recurrence of symptoms suggests a potential gap in effective long-term management or follow-up care, highlighting the need for better outpatient care coordination and chronic disease management strategies. Additionally, this pattern might indicate inadequate patient education regarding lifestyle modifications, medication adherence, or recognizing early warning signs that warrant timely medical intervention.

The observation that 60% of patients presenting with AAP reported recent dietary changes provides significant insight into the potential factors contributing to their symptoms. This finding suggests that dietary habits may play a critical role in the onset and exacerbation of abdominal pain, possibly triggering or aggravating underlying gastrointestinal conditions. Dietary habits have been increasingly recognized as playing a critical role in the onset and exacerbation of abdominal pain. A study analyzing data from the UK Biobank and NHANES indicated that a pro-inflammatory diet, characterized by high energy-adjusted Dietary Inflammatory Index (E-DII) scores, is associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing abdominal pain, both in frequency and severity.[25] Similarly, a cross-sectional study in Greek children found that those with functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) reported higher consumption of junk food and lower intake of fish, suggesting these dietary patterns may exacerbate symptoms.[26] Additionally, a pilot study indicated that insufficient fiber intake and reduced physical activity could increase the severity of gastrointestinal symptoms in children with functional abdominal pain (FAP).[27] Furthermore, irregular dietary habits, such as inconsistent meal patterns and high intake of cereals and sweets, have been linked to more severe symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).[28] These findings underscore the importance of dietary management in the prevention and treatment of abdominal pain.

The present study demonstrates a significant negative correlation between current medication use and the duration of abdominal pain symptoms (r = -0.395, p < 0.001), indicating that patients on medication tend to experience shorter symptom durations. This relationship suggests that individuals on medication may have better access to healthcare, enabling earlier intervention and management of pain. Additionally, these patients might exhibit heightened health awareness, leading them to seek medical attention promptly, thereby reducing the duration of symptoms. The medications themselves, which could include pain relief or treatment for underlying conditions, may directly contribute to this effect. However, the study’s limitations, such as the lack of detailed information on the types of medications and patient compliance, warrant caution. Future research should explore these variables to better understand how current medication use influences abdominal pain duration and to improve patient outcomes in emergency settings.

This study on the clinical presentation of AAP in the ER of a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan presents several strengths. The structured and detailed survey form facilitated a comprehensive collection of demographic and clinical data, allowing for a thorough analysis of various factors influencing AAP presentations. The inclusion of a broad patient demographic, covering all genders and adults aged 18 and above, ensured a diverse and representative sample, enhancing the study’s relevance to the general population. However, the study also has notable limitations. Being a cross-sectional study, it provides only a snapshot of AAP presentations at a specific time, limiting the ability to draw causal inferences or observe changes over time. The single-center nature of the study may restrict the generalizability of the results, as it reflects the patient population and clinical practices of one tertiary care hospital, potentially differing from other settings. The exclusion criteria, which omitted patients with chronic abdominal pain, recent surgery, or language barriers, may have introduced selection bias, affecting the study’s comprehensiveness. Furthermore, the reliance on self-reported data introduces the potential for recall bias, as patients may not accurately recall or report their symptoms and medical histories. The lack of follow-up data is another limitation, as it prevents assessment of patient outcomes and the effectiveness of interventions. Finally, while the study’s sample size of 144 participants provides valuable insights, it may still be insufficient to detect smaller effects or differences in subgroup analyses, limiting the statistical power of the findings.

Based on the findings and limitations of this study, several recommendations can be made for future research and clinical practice. First, longitudinal studies are needed to track patients with AAP over time, providing insights into the progression, management outcomes, and long-term implications of various presentations. This approach would help establish causal relationships and better understand the natural history of AAP. Expanding the study to multiple centers, including rural and different levels of healthcare facilities, would enhance the generalizability of the results and provide a more comprehensive picture of AAP across diverse settings. Additionally, including a broader range of patients, particularly those with chronic abdominal conditions and non-native language speakers, would address potential biases and ensure a more inclusive understanding of AAP presentations.

Future research should also focus on integrating more objective diagnostic tools, such as imaging studies and laboratory tests, to supplement self-reported data and minimize recall bias. Incorporating these objective measures can improve diagnostic accuracy and provide a clearer picture of the clinical landscape. Moreover, exploring the impact of socio-economic and cultural factors on AAP presentations and management outcomes would provide valuable insights into the broader context influencing patient experiences and healthcare delivery. Finally, developing standardized guidelines for the management and follow-up of patients presenting with AAP could improve clinical outcomes and streamline care processes, ensuring timely and effective interventions. These recommendations aim to build on the current study’s findings and address its limitations, ultimately enhancing the understanding and management of AAP in the ER setting.

Overall, these findings call for the development of comprehensive, culturally sensitive educational programs and healthcare policies to improve early diagnosis, management, and prevention of AAP in Pakistan. They also underscore the importance of training healthcare providers in the latest diagnostic techniques and management strategies, ensuring better patient outcomes and reducing the burden on emergency healthcare services.

Conclusion

This cross-sectional study draws significant insights into the clinical presentations of AAP and their management in the ER of a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan. It, therefore, stresses the need for better pain management strategies, comprehensive triage systems, and more education for health providers. Overall, improving the treatment and diagnosis, as well as the proper management of AAP in emergency settings, would eventually improve patient care and outcomes in Pakistan’s healthcare system.

References

- Tamchès E, Buclin T, Hugli O, et al. Acute pain in adults admitted to the emergency room: development and implementation of abbreviated guidelines. Swiss Med Wkly. 2007;137(15-16):223-227. doi:10.4414/smw.2007.11663 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Patterson JW, Kashyap S, Dominique E. Acute Abdomen. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. Acute Abdomen

- Osterwalder I, Özkan M, Malinovska A, Nickel CH, Bingisser R. AAP: Missed diagnoses, extra-abdominal conditions, and outcomes. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):899. doi:10.3390/jcm9040899 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Vaghef-Davari F, Ahmadi-Amoli H, Sharifi A, Teymouri F, Paprouschi N. Approach to Acute Abdominal Pain: Practical Algorithms. Adv J Emerg Med. 2019;4(2):e29. doi:10.22114/ajem.v0i0.272 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Jameel A, Anwar I, Laique MH. Etiological spectrum of surgical acute abdomen among patients attending emergency department. Pak J Med Health Sci. 2023;17(5):94. doi:10.53350/pjmhs202317594 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Reintam Blaser A, Starkopf J, Malbrain ML. Abdominal signs and symptoms in intensive care patients. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2015;47(4):379-387. doi:10.5603/AIT.a2015.0022 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bhagat TS, Agarwal A, Verma R, et al. To study the epidemiology and clinical profile of adult patients with AAP attending tertiary care hospital. 18(40):157. (PDF) To study the epidemiology and clinical profile of adult patients with acute abdominal pain attending tertiary care hospital

- Sauerland S, Agresta F, Bergamaschi R, et al. Laparoscopy for abdominal emergencies: evidence-based guidelines of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery. Surg Endosc. 2006;20(1):14-29. doi:10.1007/s00464-005-0564-0 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cervellin G, Mora R, Ticinesi A, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of AAP in a large urban emergency department: retrospective analysis of 5,340 cases. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(19):362. doi:10.21037/atm.2016.09.10 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Chanana L, Jegaraj MA, Kalyaniwala K, Yadav B, Abilash K. Clinical profile of non-traumatic AAP presenting to an adult emergency department. J Family Med Prim Care. 2015;4(3):422-425. doi:10.4103/2249-4863.161344 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Coccolini F, Improta M, Sartelli M, et al. Acute abdomen in the immunocompromised patient: WSES, SIS-E, WSIS, AAST, and GAIS guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2021;16(1):40. doi:10.1186/s13017-021-00380-1

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Thakur JK, Kumar R. Epidemiology of AAP: a cross-sectional study in a tertiary care hospital of Eastern India. Int Surg J. 2019;6(2):345-348. doi:10.18203/2349-2902.isj20190380 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Nurmahomed N, Bickerton R, Bronze C. Assessment of abdominal pain in older people: a quality improvement project in the emergency department. Future Healthc J. 2022;9(Suppl 2):94. doi:10.7861/fhj.9-2-s94 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholarv

- Taber JM, Leyva B, Persoskie A. Why do people avoid medical care? A qualitative study using national data. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(3):290-297. doi:10.1007/s11606-014 3089-1

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Lyon C, Clark DC. Diagnosis of AAP in older patients. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(9):1537-1544. Diagnosis of AAP in older patients

- Swinnen TW, Westhovens R, Dankaerts W, de Vlam K. Widespread pain in axial spondyloarthritis: clinical importance and gender differences. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20(1):156. doi:10.1186/s13075-018-1626-8

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Arendt-Nielsen L, Bajaj P, Drewes AM. Visceral pain: gender differences in response to experimental and clinical pain. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(5):465-472.

doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.03.001 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Boyle MJ, Lin-Martore M, Graglia S. Point-of-care ultrasound in the assessment of appendicitis. Emerg Med J. 2023;40(7):528-531.

doi:10.1136/emermed-2022-212433 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Patel HK, Kovacic R, Chandrasekar VT, et al. Correlation of gastrointestinal symptoms at initial presentation with clinical outcomes in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: results from a large health system in the Southern USA. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67(11):5034-5043. doi:10.1007/s10620-022-07384-0 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Banoub CM, Sobhy TM, Elsammak AA, Alsowey AM. Role of ultrasound in the assessment of pediatric non-traumatic gastrointestinal emergencies. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2021;83(1):988-994. doi:10.21608/ejhm.2021.159674

Crossref | Google Scholar - Lakhoo K, Almario CV, Khalil C, Spiegel BMR. Prevalence and characteristics of abdominal pain in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(9):1864-1872.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.065 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Colomier E, Melchior C, Algera JP, et al. Global prevalence and burden of meal-related abdominal pain. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):71. doi:10.1186/s12916-022-02259-7 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kshirsagar VY, Nagarsenkar S, Ahmed M, Colaco S, Wingkar KC. Abdominal epilepsy in chronic recurrent abdominal pain. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2012;7(3):163-166. doi:10.4103/1817-1745.106468 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Koop H, Koprdova S, Schürmann C. Chronic Abdominal Wall Pain. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113(4):51-57. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2016.0051 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Li L, Zhuang Y, Ran Y, et al. Association between pro-inflammatory diet and abdominal pain: cross-sectional and case-control study from UK biobank and NHANES 2017-2020. Pain Med. Published online April 23, 2024. doi:10.1093/pm/pnae028 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Chouliaras G, Kondyli C, Bouzios I, et al. Dietary habits and abdominal pain-related functional gastrointestinal disorders: a school-based, cross-sectional analysis in Greek children and adolescents. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;25(1):113-122. doi:10.5056/jnm17113 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Boradyn KM, Przybyłowicz KE, Jarocka-Cyrta E. The role of selected dietary and lifestyle factors in the occurrence of symptoms in children with functional abdominal pain: a pilot study. Acta Sci Pol Technol Aliment. 2020;19(3):291-300.

doi:10.17306/J.AFS.2020.0833 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Nilholm C, Larsson E, Roth B, Gustafsson R, Ohlsson B. Irregular dietary habits with a high intake of cereals and sweets are associated with more severe gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS patients. 2019;11(6):1279.

doi:10.3390/nu11061279 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

The authors declare that no financial grants were obtained for the completion of this paper.

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Saad Shafi

Department of Medicine

Fazaia Ruth Pfau Medical College, Karachi, Pakistan

Email: saadshafi663@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Touseeq Haider, Ifra Manzoor, Rubab Nafees, Syed Haffi Hussain, Hareem Shafi, Yousuf Ali Lakdawal

Department of Medicine

Fazaia Ruth Pfau Medical College, Karachi, Pakistan

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Ethical Approval

The research study obtained ethical clearance from the Institutional Review Board of FRPMC (Ref No: FRPMC-IRB-2024-58). This study followed the ethical considerations of the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Yousuf Ali L, Saad Shafi, Touseeq H, et al. Evaluating the Clinical Presentation of Acute Abdominal Pain in the Emergency Room at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Pakistan: A Cross-Sectional Study. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622411. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622411 Crossref