Author Affiliations

Abstract

Lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs) are a group of unusual genetic disorders characterized by defective lysosomal enzymes responsible for substrate accumulation within cells. This disturbance hinders normal cellular functionality and consequent progressive organ damage. Pompe disease, Gaucher disease (GD), and Fabry disease are relatively common examples of LSDs. In Pompe disease, glycogen accumulates in muscle tissues due to the deficiency of acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA), whereas in GD, glucocerebroside accumulates because of the deficiency of glucocerebrosidase, and in Fabry disease, globotriaosyl ceramide accumulates because of the deficiency of alpha-galactosidase A. Different therapeutic strategies are available for these disorders. Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) provides missing enzymes to limit substrate accumulation while substrate reduction therapy (SRT) decreases substrate levels and alleviates storage stress. Chaperone-mediated therapy (CMT) stabilizes misfolded enzymes to increase lysosomal activity. Gene therapy approaches are under investigation, with some using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) technology to induce permanent correction of genetic defects by transferring functional genes. Proteostasis regulators maintain lysosomal function and restore the cellular environment, in turn, restoring enzyme function. Stem cell transplantation offers a potential supply of functional lysosomal enzymes from donor cells. Therefore, the combination of all these emerging approaches provides fresh hope for enhancing therapeutic outcomes against LSDs, overcoming their limitations, and improving the quality of life for LSD patients.

Keywords

Lysosomal storage disease, Pompe disease, Gaucher disease, Fabry disease, Globotriaosyl ceramide, Proteostasis.

Introduction

LSDs are recessive metabolic disorders resulting predominantly from enzyme deficiency at the lysosomal level and constitute an accumulation of undegraded substrate. This storage condition causes a wide range of clinical manifestations that depend on the specific substrate as well as on the site of accumulation.[1] Three of the 70 monogenic disorders of lysosomal catabolism that make up LSDs are X-linked, but the majority are inherited as autosomal recessive abnormalities. Genes encoding lysosomal proteins, including transporters, enzyme modifiers, activators, proteases, lysosomal glycosidases, and integral membrane proteins, are mutated in these illnesses. The function of the encoded protein is impacted by mutations in lysosomal genes, which leads to lysosomal dysfunction and the slow buildup of substrates (also known as “storage”) inside the lysosome, which eventually causes cell failure and death.[2,3]

Classifying storage sites according to a substrate, which includes oligosaccharidoses, gangliosidoses, sphingolipidoses, mucopolysaccharidoses, and others. Tay-Sachs disease, a disorder of the central nervous system, is caused by the absence of hexosaminidase A acting on the second monosialic ganglioside (GM2), which can be measured in the blood. Most lysosomal proteins are derived from housekeeping genes that are expressed throughout the body, but storage only takes place in cells for which a substrate is available. Although each condition is uncommon, the prevalence of LSDs as a group is 1 in 7000–8000 live births. Mutational studies and certain enzyme testing validate the diagnosis for each of these illnesses. And this is why urinary mucopolysaccharides and oligosaccharides might be quite useful for screening; however, normal or elevated levels of them can be obtained from healthy neonates nonspecifically.[4]

A single clinically characterized condition can result from several enzymatic anomalies. Variations in Sanfilippo illness, mucopolysaccharidosis type III (MPS III), brought on by defects in any one of the four hydrolases, could serve as an illustration. Specific mutations or types of mutations may have a correlation to outcomes, even when gene-phenotype associations appear weaker, especially since patients with GD who have the same mutations may exhibit symptoms from childhood or stay asymptomatic until adulthood. Although there is evidence for random inactivation, the degree of X-chromosomal inactivation may be the dominant factor influencing the severity and range of clinical symptoms in women with X-linked lysosomal storage illnesses, such as Fabry disease.[4]

Loss-of-function mutations in one of the more than 50 soluble enzymes, such as lipases, proteases, sulfatases, or proteins involved in their synthesis or trafficking, cause substrate buildup and alterations in lysosomal storage. Initial signs may be present in many lysosomal storage disorder patients who are clinically normal at birth. This implies that lysosomal dysfunction has little effect on the intricate processes of early brain development, including neural induction, axis establishment, neuronal differentiation and migration, and synapse creation. Furthermore, exposure to a range of LSDs typically results in children reaching early developmental milestones, suggesting that lysosomal storage has minimal impact on neuronal function and maturation at these early stages.[5]

The type of disease and other variables, like age at onset, affect the signs and symptoms of LSDs. Certain LSDs, like β-glucuronidase deficiency, are present from birth, whereas others, including infantile GM1-gangliosidosis, Krabbe disease, or Tay-Sachs disease, are identified between the ages of two and six months. Like some mucopolysaccharidoses (MPSs), other LSDs, like metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD), manifest symptoms in late infancy or youth. While many LSDs first appear in childhood, some, such as adult GM2-gangliosidosis, appear in the second decade of maturity. LSD is identified by visual abnormalities, seizures, organomegaly (especially significant with prominent dysmorphic traits and bone involvement that characterize the MPSs), failure to fulfill developmental milestones, and neuromotor regression. Adult GM2-gangliosidoses are instances of late-onset (adult) kinds that show neurological deficits along with psychiatric symptoms of depression or psychosis. The adult variants are also impacted by MLD in different ways. Because LSDs cause neurological and other problems over time, patients and their families experience severe morbidity and a lower quality of life; typically, mortality happens in early life.[6]

Pathophysiology

General mechanisms: In addition to breaking down and recycling macromolecules (such as proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids), lysosomes serve as metabolic centers that regulate calcium signaling, amino acid and ion homeostasis, and nutritional sensing. These organelles are always changing; they merge with phagosomes, autophagosomes, and the plasma membrane, and as a result, they play a crucial part in communication between cells and the extracellular matrix, infection response, and homeostasis maintenance. Furthermore, late endosomes and lysosomes create functional membrane contact sites by attaching to other intracellular organelles like mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum without merging with them. The flow of metabolites, calcium ions, and lipids between the organelles is made possible by these membrane structures, which function as signaling microdomains. The functional features of each tethered organelle are defined by the lipid and protein structure of these contact sites. For instance, lysosomal dynamics and mitochondrial fission are regulated by the GTP hydrolysis of the Ras-related protein Rab7a (RAB7; also known as RAB7A) via mitochondria–lysosome interface sites. Thus, it stands to reason that in an LSD, modifications to the endosomal and lysosomal membrane composition brought on by a decrease in lysosomal activity could influence the biochemical properties and, in turn, the activities of these microdomains.[2]

Cellular pathophysiology: The pathophysiology of these illnesses involves changes in signal transduction and transport, apoptosis, and inflammation. Sandhoff disease and GM2-gangliosidosis are modelled in mice lacking the β-subunit of β-hexosaminidase. Between three and four months of age, the animals start to exhibit significant neurological problems. Microglia activation and a higher frequency of apoptotic neurons are correlated with the onset of symptoms. The number of apoptotic neurons is significantly decreased when bone marrow from a healthy donor is transplanted into the afflicted mice, resulting in an extended lifespan. Remarkably, however, transplantation did not cause β-hexosaminidase to be delivered to the brain or GM2-ganglioside storage to decrease, indicating that apoptosis is not caused by neuronal storage in and of itself. Nevertheless, bone marrow transplantation significantly lowers microglia activation and, as a result, cytokine and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα) production. This implies that microglial phagocytosis is the outcome of the initial neuronal injury. When GM2-ganglioside builds up in microglia, it activates them and leads them to secrete different cytokines, which encourages apoptosis. This illustration shows that pathogenic mechanisms are the consequence of intricate interactions between various cell types rather than being merely described by cellular changes of a single cell type.[7]

Signal transduction: Signal transduction is also impacted by storage chemicals. Cultured glucosylceramide-storing hippocampus neurons with Gaucher illness respond to glutamate or caffeine stimulation by sensitizing the ryanodine receptor, which results in a markedly enhanced release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum. In neuronopathic forms of GD, this increases the cells’ sensitivity to glutamate, which damages neurons. Since glutamyl ceramide was shown to be increased by roughly 10 times in microsomes isolated from the brains of patients with neuronopathic type II GD, it is likely to operate directly on the endoplasmic reticulum. The pathophysiology of LSDs must consider the fact that increased lipid levels affect the activities of other cellular membranes in addition to the lysosomal compartment.

Cholesterol metabolism: Numerous sphingolipid storage illnesses have been shown to have changes in membrane trafficking and cholesterol distribution. Lactosylceramide in the plasma membrane is endocytosed and moved to the Golgi apparatus in healthy cells. Instead, the endocytosed lactosylceramide is found in the endosomal/lysosomal compartment of the cells of patients with different lipidoses. In many of these conditions, elevated cholesterol levels accompany this occurrence. Since the sorting of lactosylceramide towards the Golgi apparatus is corrected when cholesterol levels in lipidosis cells are reduced, elevated cholesterol levels are functionally connected to the missorting of lactosylceramide.[8]

Types of LSDs

Majorly occurring LSDs are explained below

GD: This disorder is autosomal recessive and is caused by mutations in the 11-exon glucocerebrosidase gene, which is located on chromosome 1q21. Glucocerebroside, a component of the cell membrane, is the substrate on which the enzyme operates. Glucosylceramidase Beta (GBA) receives the protein saposin C from the normal lysosome together with glucocerebroside, which causes the enzyme to become active. Glucosylceramide is hydrolyzed by the enzyme to produce ceramide and glucose. When this enzyme is absent, glucosylceramide and glycolipids build up in the lysosomes of macrophages, which are mostly found in the spleen, liver, bone marrow, brain, and osteoclasts, but are also less commonly present in the lungs, skin, kidneys, and conjunctivae.[9]

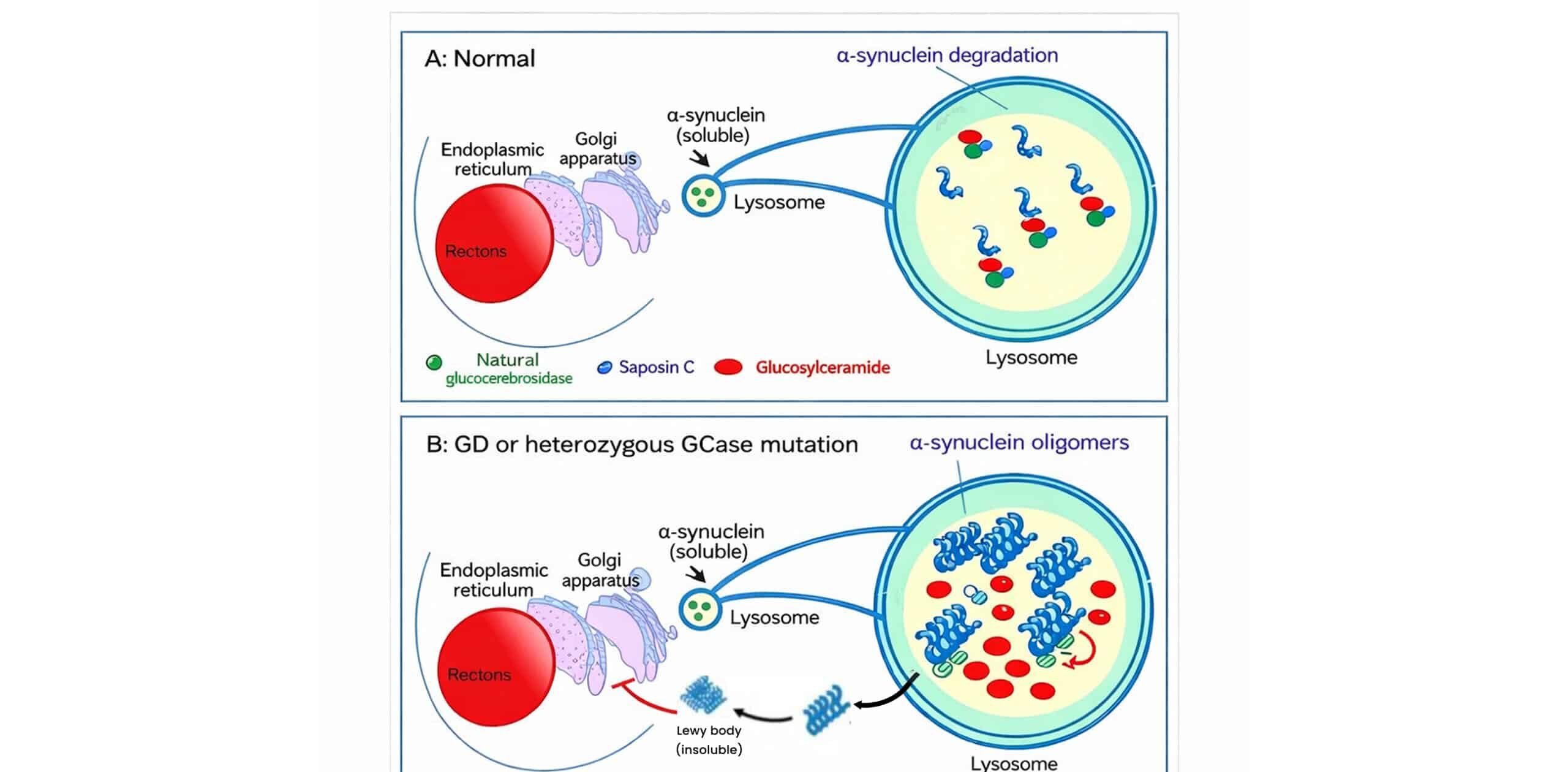

Figure 1: Role of glucocerebrosidase in α-synuclein metabolism and its disruption in GD or GBA mutations

In figure 1A, Normally, the GCase must interact with its substrate glucosylceramide (GlcCer) and α-synuclein monomers when they become lysosomal, which is essential for breakdown in an acidic pH (probably 4-5). In figure 1B, mutated or reduced GCase levels inhibit α-synuclein degradation and contribute to the accumulation of GlcCer, leading to the formation of toxic oligomers of α-synuclein that bind to mutated GCase, which hinders its activity. This, in turn, affects the functions of lysosomes and autophagy, resulting in an increase in cytoplasmic α-synuclein accumulation, leading to the formation of Lewy bodies. Mutant GCase accumulates in the ER, leading to ER stress. Saposin C is capable of modulating GCase activity for better maintenance of its functions.[10]

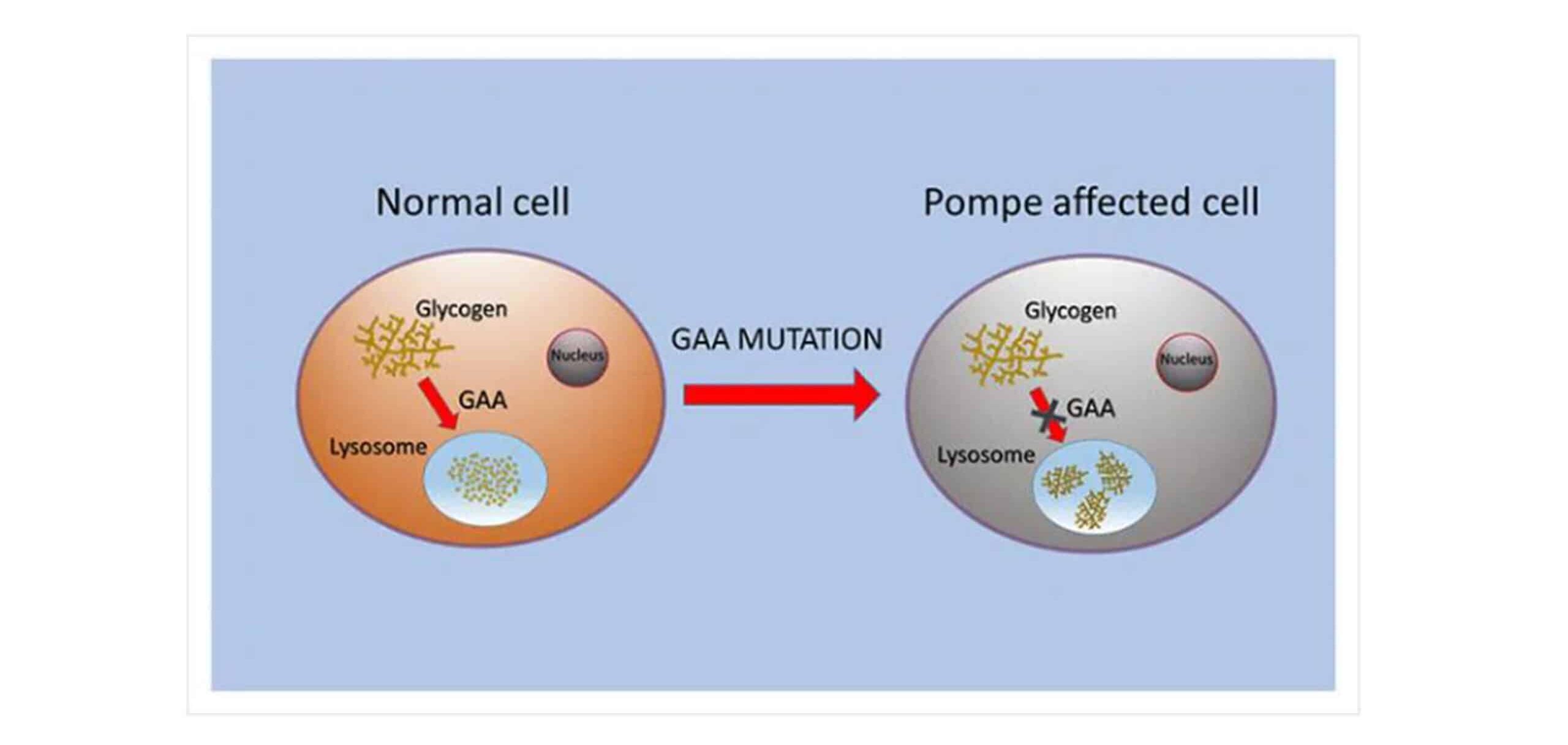

Pompe disease: Pompe disease, a type of metabolic myopathy, is a very severe type that has mutations that perturb genes that code for the enzyme that breaks down glycogen, that is, acid GAA, under acidic conditions inside the lysosome. ‘The glycogen de novo with glucose, once in the lysosome’, gets an accumulator fate due to total degradation given by GAA, due to a deficiency in the enzyme. Lysosomal accumulations of glycogen occur in different tissues, but the heart and skeletal muscles are particularly involved. The disease is also known as “Type II glycogen storage disease (GSDII)” or “Acid maltase deficiency.[11,12]

Figure 2: Schematic demonstration showing the alteration of GAA responsible for lysosomal glycogen storage within the Pompe-affected cells

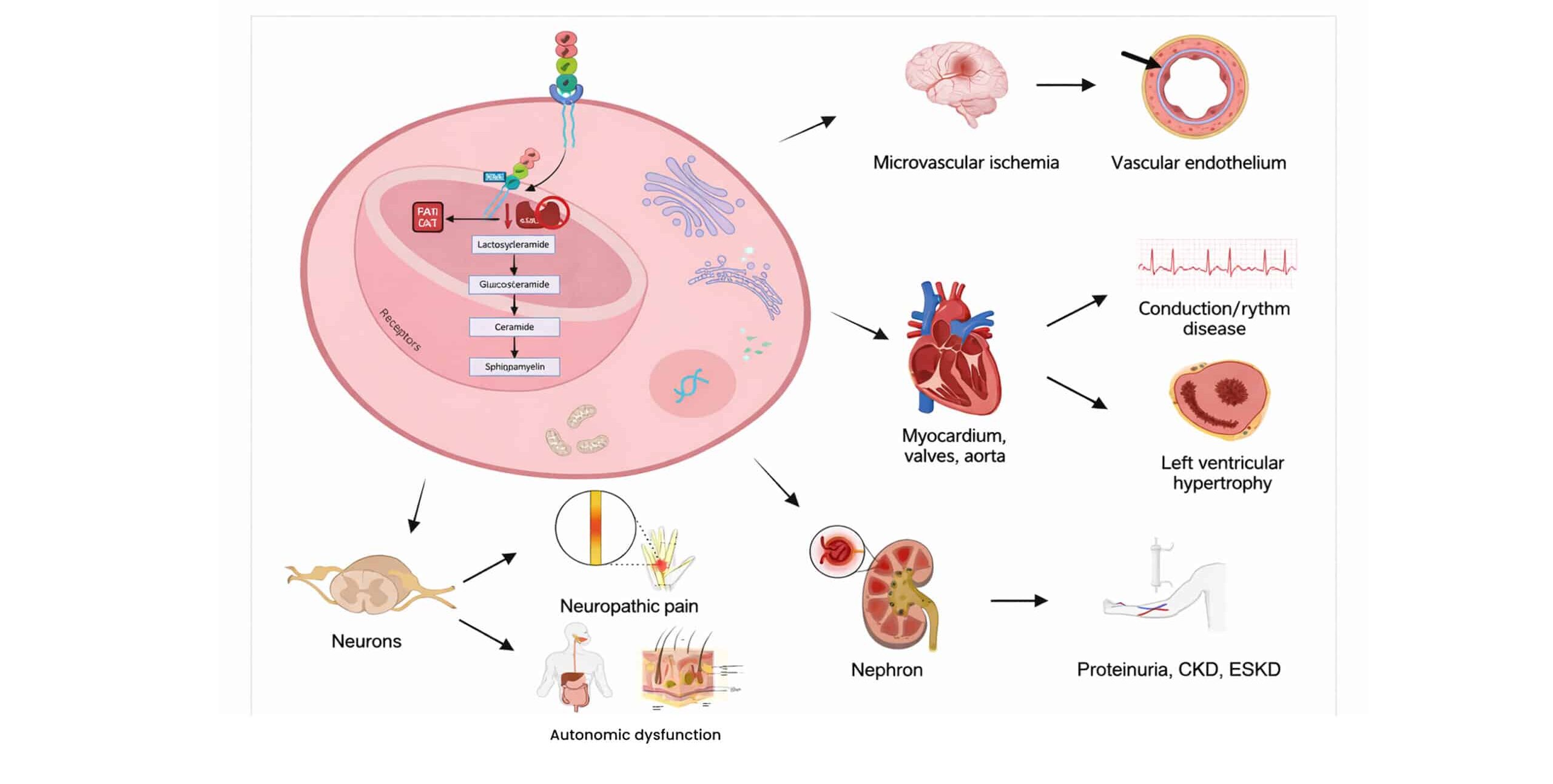

Fabry disease: Fabry disease is a progressive metabolic inborn error that destroys a patient’s body and, most importantly, has dependent factors on cellular dysfunction and microvascular pathologies in early stages owing to the deposition of lysosomal glycosphingolipid. A deficit or absence of lysosomal exoglycohydrolase-alpha-galactosidase A (or alpha-D-galactoside galactohydrolase; EC 3.2.1.22; alpha-gal A) gives rise to accumulation of globotriaosylceramide (Gb3 or GL-3; also, ceramidetrihexoside (CTH) and related glycosphingolipids (galabiosylceramide) in lysosomes most progressively.[13]

Figure 3: Pathophysiology of Fabry disease

Pharmacotherapy in lysosomal storage disease:

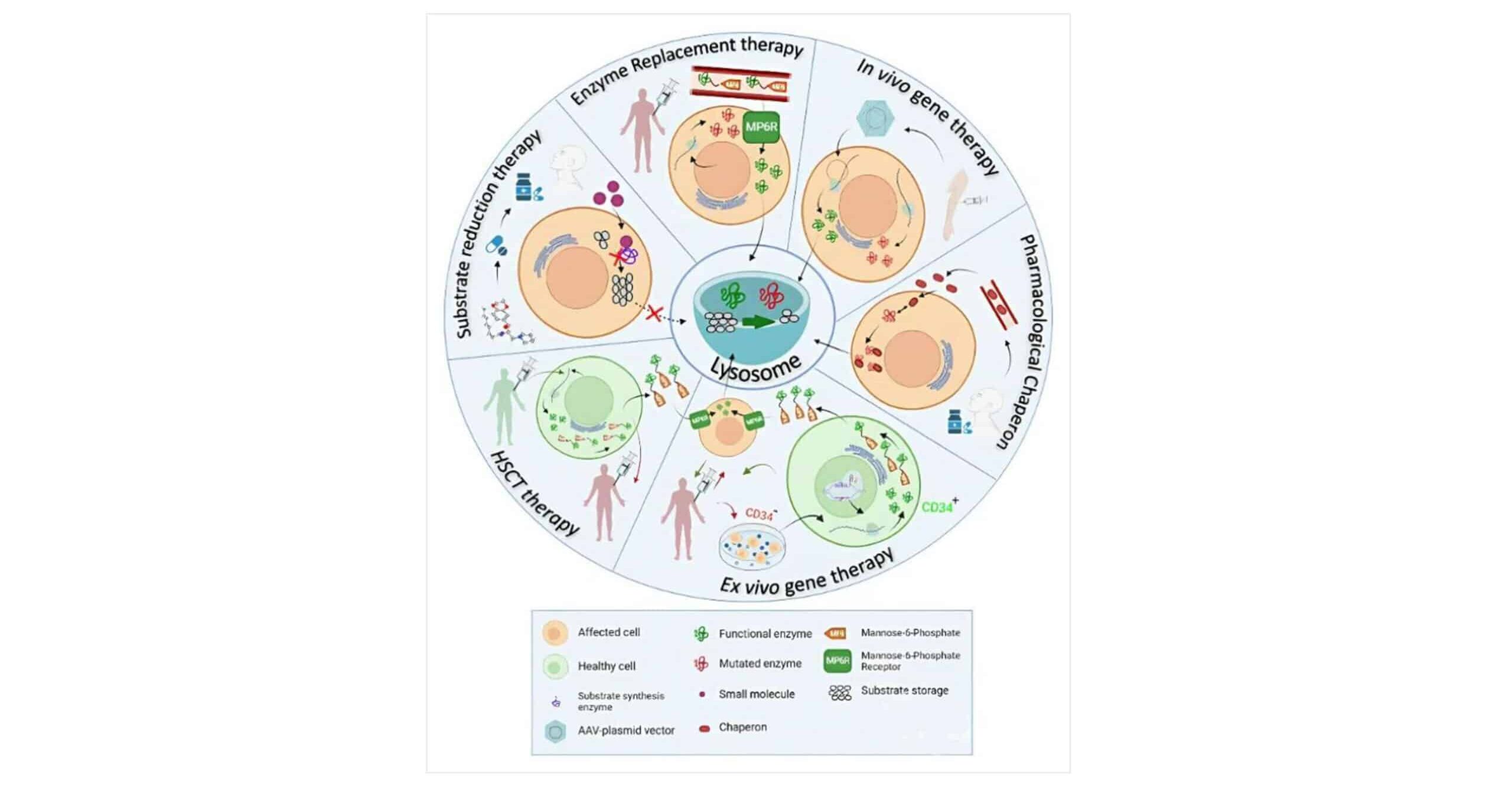

Figure 4: Therapeutic approaches in LSDs

Physiology of the lysosome is at the basis of the therapeutic strategies proposed to treat LSDs. All these approaches aim to restore substrate production/cleavage balance in the lysosome.[14]

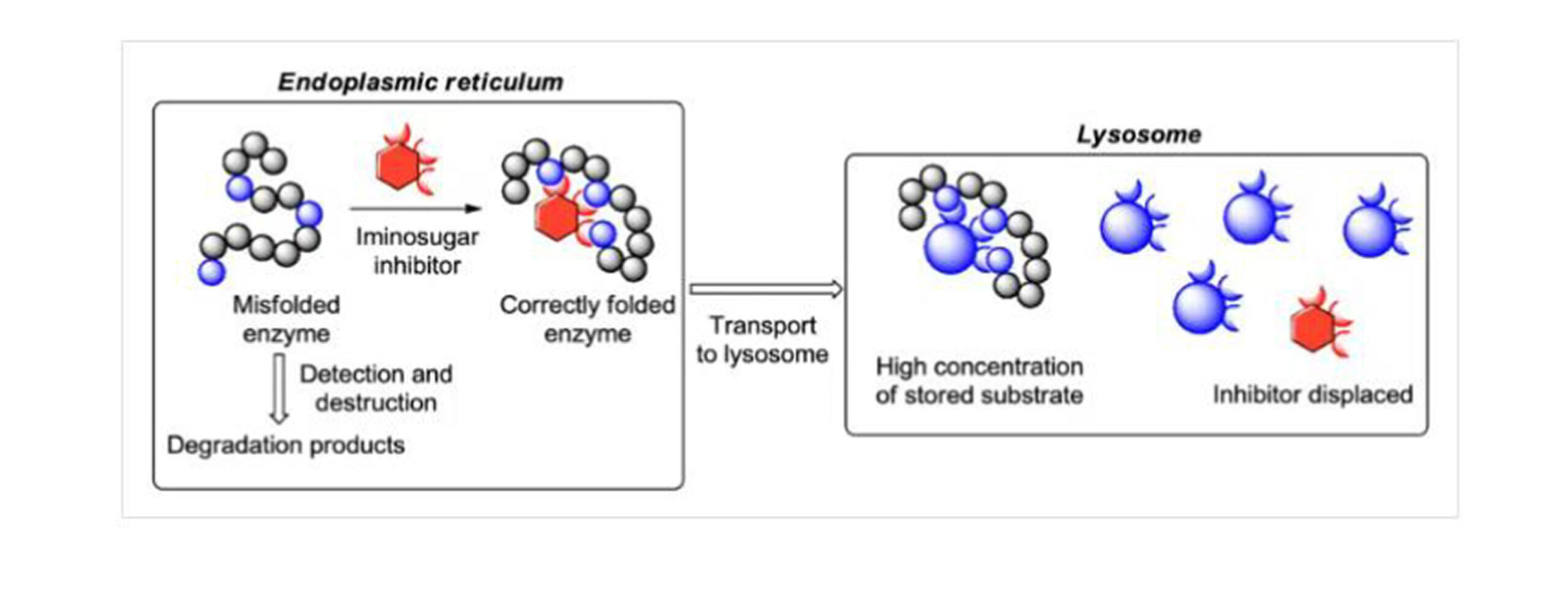

CMT: Pharmacological chaperone therapy tackles the misfolded proteins caused by single amino acid changes or missense mutations, which lead to degradation or mis trafficking and ultimately loss of function. Using small-molecule chaperones, misfolded mutant proteins are refolded and stabilized, thereby allowing proper trafficking and restoration of activity. This modality is currently being explored in clinical trials for LSDs. Chaperones further support the efficacy and stability of recombinant enzyme therapy, such as that used in ERT for Pompe, Fabry, and GD. Trials examining the combination of ERT with chaperones are ongoing.[15]

Figure 5: Mechanism of CMT

In glycosphingolipidosis, the genetic mutations that can be seen to alter high misfolding rates of glycosidase hinder the proper folding and transport of this enzyme. The iminosugars are powerful reversible inhibitors of glycosidases and can act as pharmacological chaperones by binding to the active site of the enzyme, stabilizing the structure of the enzyme, and promoting its proper folding and transport to the lysosome.[16]

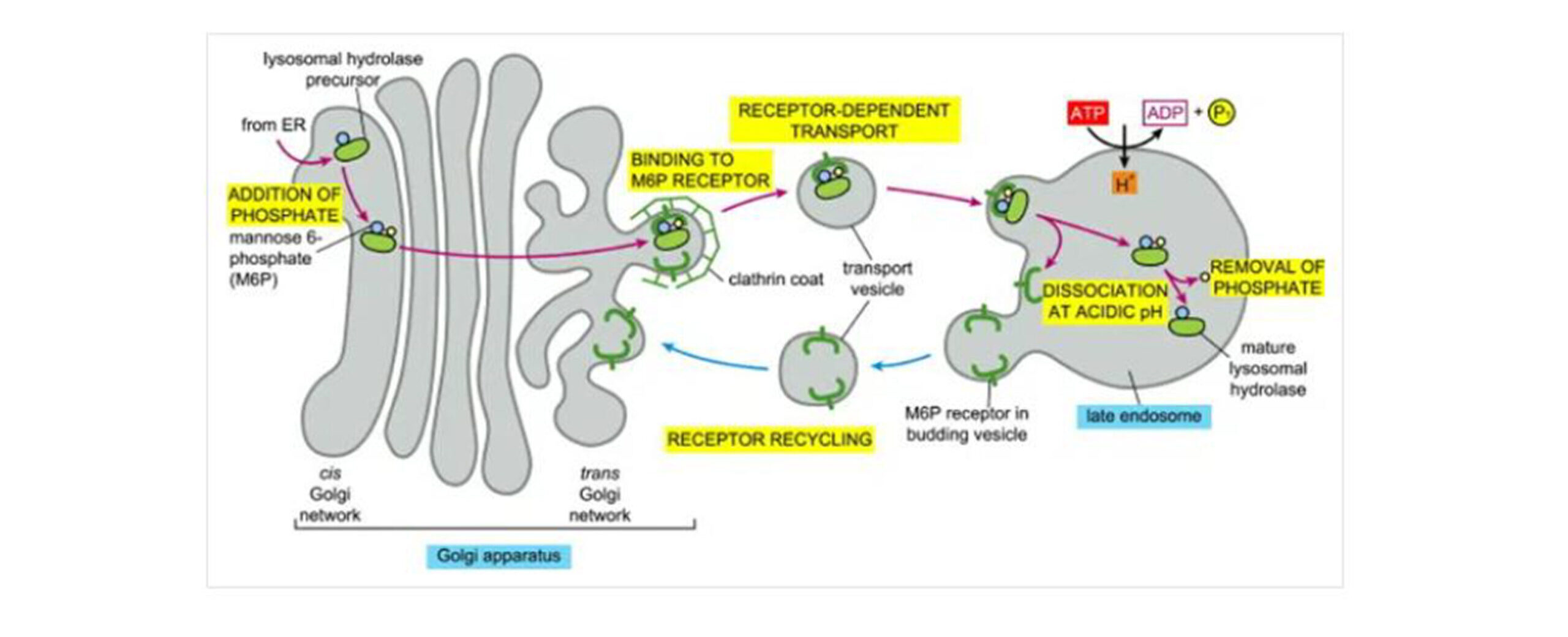

ERT: ERT has now transformed the medical scenario into LSDs. The first observation of this phenomenon, “cross-correction of lysosomal enzymes secreted by one cell into another,” was noted in 1970. However, prior to deciphering the molecular mechanisms underpinning the process, this type of therapy could not be undertaken. Such momentous breakthroughs as the mannose (1978) and mannose 6 6-phosphate (1992) recognition systems made possible the paradigm shift for targeted delivery of enzymes. The ‘mannose receptor’, primarily in the reticuloendothelial system, and the ‘mannose 6-phosphate receptor’, widely expressed in cells, facilitated efficient lysosomal delivery of the enzymes, making ERT effective for LSD treatment.[17]

Figure 6: Transport of newly synthesized lysosomal hydrolases to lysosomes

After synthesis, lysosomal hydrolase precursors are covalently modified with groupings of mannose 6-phosphate (M6P) within the cis-Golgi network. Their segregation in the trans-Golgi from all other types of proteins is because they are recognized by M6P receptors present on the adaptins of clathrin coats from the modified lysosomal hydrolases. Consequently, these vesicles are formed, pinched off from the trans-Golgi network, and fused into the mature endosome. Subsequently, the low pH in the late endosome causes dissociation of the hydrolyses from the M6P receptors, which recycle empty M6P receptors to the Golgi apparatus for further transport. The identity of the coat promoting the vesicle budding in the pathway of the M6P receptor recycling remains unknown. Therefore, dephosphorylation in the late endosome prevents the return of the hydrolases to the Golgi apparatus attached to the receptor.[18]

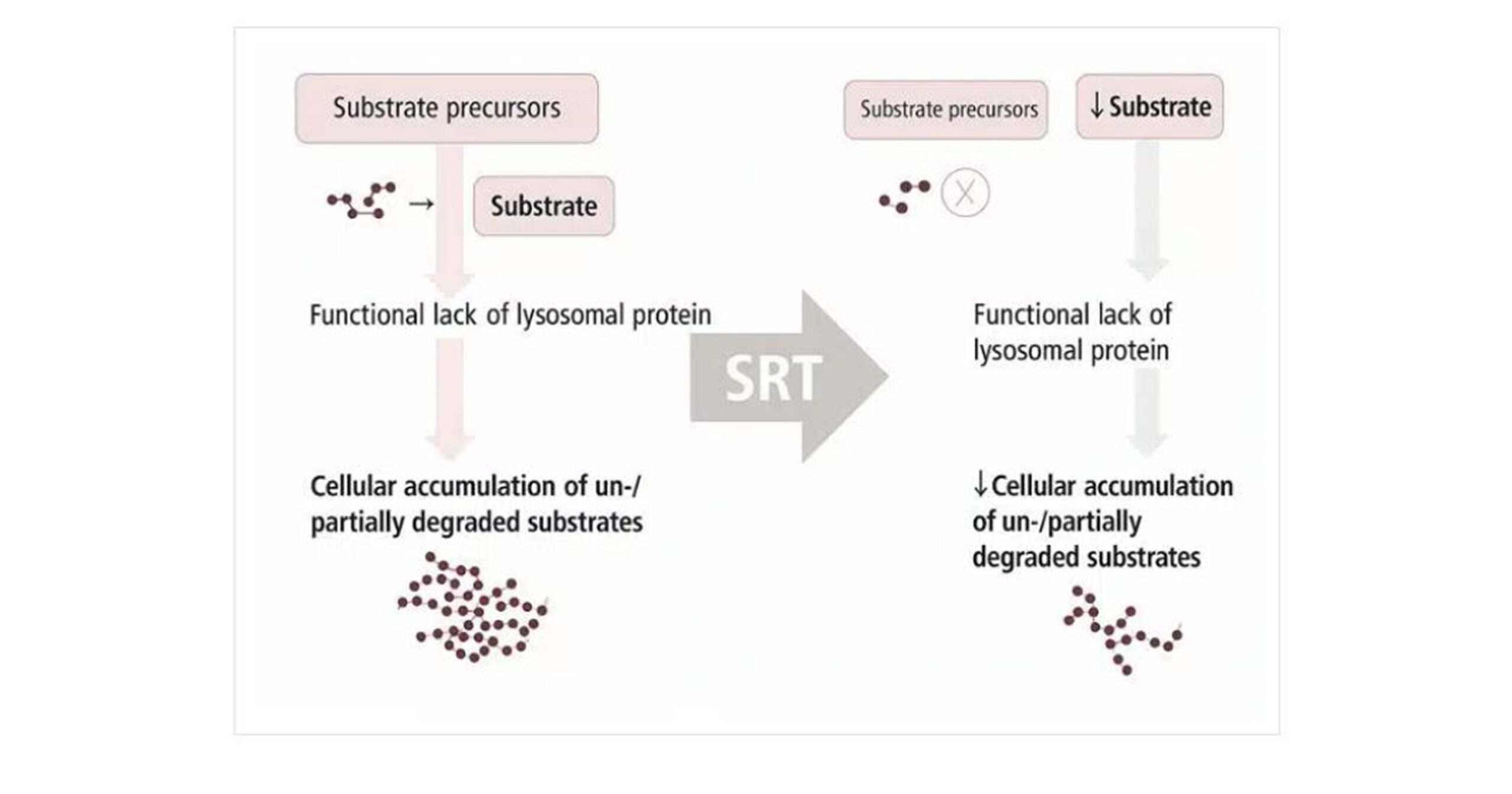

SRT: SRT reduces enzymatic substrate entry into the catabolically challenged lysosome by partially inhibiting the synthesis of the accumulated product. Miglilustat was created as a small-molecule oral substrate reduction treatment for GD. Adult patients with mild to moderate GD symptoms who are unable to receive or maintain ERT or who continue to exhibit fatal disease activity despite optimal enzyme dose can safely take miglustat (Zavesca), which is licensed for use in this condition. In certain situations, the medication and ERT can be used together.[19,20]

Figure 7: Mechanism of SRT

Proteostasis regulators: Proteostasis is a complex system that maintains protein synthesis, folding, trafficking, aggregation, and destruction. Alternative small-molecule-based techniques have been proposed to restore the altered enzymes in LSDs. Chaperones are ligands that can rescue a single protein by preferentially attaching to defective proteins. For GD and GM2 gangliosidosis (Tay-Sachs disease), two distinct LSD brought on by a lack of β-hexosaminidase A, proteostatic control was suggested as a treatment strategy. The TFEB gene, which is overproduced in fibroblasts from GD, has also been utilized to control proteostasis. Additionally, downregulating the ER-resident protein FKBP enhanced the proteostasis of β-glucocerebrosidase.[21]

Gene therapy in LSDs: The development of gene therapy procedures has focused on rare disorders, including LSDs, due to their advantageous characteristics. Most LSDs are brought on by mutations in the genes that produce hydrolytic enzymes, which are catalytic by nature and are effective at low expression levels. According to the literature, no store buildup would be observed if residual activity were just 10% of physiological values. Cross-correction helps to prevent substrate accumulation in many target organs, and gene therapy vectors do not transduce all cells. Several other drugs are currently undergoing clinical research. However, Orchard Therapeutics Limited-200 (OTL-200) is currently the only approved gene therapy for LSDs regarding metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD).[22]

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT): Prior to the introduction of ERT, the primary therapy for LSDs included HSCT, which is still very effective in a few diseases affecting the central nervous system. The significant advantage of HSCT is that the donor cells activate the synthesis of necessary enzymes, which are known to migrate to the brain and delay neurocognitive deterioration. The most effective procedure is early in the progression of man’s disease, improving central nervous system (CNS) symptoms and quality of life. HSCT is completed in mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) I, Krabbe disease, and the attenuated forms of metachromatic leukodystrophy. HSCT would be applicable for children with MPS manifestation by 2.5 years since the effects of the procedure will improve the clinical effects in these young patients suffering severe MPS I and could even extend life expectancy. The outcome in MLD and Krabbe disease depends on the patient’s disease phenotype and progression stage. Drawbacks would be, however, high rates of rejection and mortality that are due to infections as well. These factors and the variable level of engraftment limit this strategy to very few cases.[23]

Personalized medicine and tailored approaches

Genetic profiling: Genetic profiling, also known as deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) profiling or DNA fingerprinting, is a process of analyzing individual genetic information. Identifying variations in genes that may influence health, disease susceptibility, and treatment response. It is crucial to emphasize that profiling is the process by which such a combination of traits is linked with target attributes used for decision making, e.g., concerning the risk of developing a disease. The application of genetic profiling in medical treatments possesses the potential to revolutionize personalized medicines and therapies and improve patient outcomes. Genetic profiling is used in healthcare and biomedical research to associate genetic traits with increased or decreased likelihood of developing and overcoming certain diseases.[24] Thus, for further discussions on the potentials and problems of genetic profiling, we will take up LSDs, a group of more than 70 diseases characterized by lysosomal dysfunction, mostly inherited as autosomal recessive. These disorders are rare individually, but together they impact about 1 in 5000 live births. Genetic profiling strategies for treating lysosomal disorders have become increasingly crucial in developing targeted therapies. It also offers numerous benefits in the treatment and provides valuable insights and opportunities for improving patient care.[25]

CRISPR: The gene-editing approach known as clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats CRISPR/Cas9 is generating a significant disruption in scientific research. It entails the rapid and easy manipulation of cells and organisms [26]. LSD can be treated with this bioengineered equipment. Terminally differentiated cells can be taken from the patient, generated, and reprogrammed for autologous stem cell transplantation for somatic-cell applications. While the alteration of cells from humans using other gene editing tools has reached clinical use in recent years, the usage of CRISPR/Cas9-RGNs remains in the early phases of clinical development. The genetic transformation into a parental embryonic line from the (CRISPR)/Cas9 edited gene process enables the creation of isogenic lines that represent specific mutations of the LSD genes that are easier to compare. LSDs are being studied using CRISPR knock-out models. Implications for better knowledge, possible treatments, and improved modeling could result in the creation of new LSD treatments.[27]

Challenges in the pharmacological management of lysosomal storage disease

Perhaps in most LSDs, there are no proven cures, but there are some therapies that are considered beneficial in the treatment of LSDs. But keep in mind that applying these therapies has challenges. The initial mode of treatment for LSDs seemed to be bone marrow transplant or HSCT from allogeneic donors. In this treatment, the blood stem cells are transferred to the patient from paired donors to replace the cells in the tissues that have been damaged and to secrete useful acid hydrolases into the bloodstream and extracellular matrix. Where the injured cell will endocytose the enzymes through M6P receptors [21], such treatment is restricted to a few LSDs, including late-onset Krabbe disease and MPS I, even though it aids clinical improvement in their neurocognitive status. Also, due to the scarcity of matched donors among the family members, HSCT witnessed a high morbidity rate and various safety concerns.[28]

If we talk about ERT, ERT is the most successful medical care available for LSDs currently, but the main disadvantage is that it is only applicable for non-neurological LSDs. ERT is well tolerated, but its effectiveness is generally dose dependent, and it is lifelong, and in some cases, a higher dose is required to guarantee that specific organs receive the substrate for clearance, such as for type 1 GD. ERT is only applicable to visceral organs and peripheral body sites.[29] Moreover, the ERT is an expensive treatment option that costs about 1000 us dollars per year per patient. Moreover, 75% of patients with LSDs with neurological disorders cannot be treated effectively. The main reason is the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which creates an obstacle for hydrophilic enzymes required for the treatment of LSDs.[30] Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) are built up in different tissues in mucopolysaccharidosis, which causes damage to the heart and other organs, even the CNS, and enzymes are incapable of crossing the blood-brain barrier, so somatic symptoms are controlled, but the CNS symptoms are not.[31]

If we talk about chaperone therapy, which is only possible for the patient who has responsive mutations, and moreover, it is particularly found in the enzymatic protein domain. The fact that chaperones have been discovered so far for the management of LSDs is that they are only active site-directed molecules that are possible competing inhibitors of target enzymes.[32] CMT is only applicable for a small percentage of mutations. Not all missense mutations are susceptible to chaperones, nor do all LSD patients have missense mutations. CMT depends on the type of mutation present.[33] Preexisting immunity to vectors themselves is a significant barrier that many gene therapy vectors must overcome. This can be significantly constrained by applying these strategies to the human population, especially using the adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene. Most humans have preexisting humoral immunity to AAV serotypes. Even low tires of antibodies can block the AAV gene therapy.[34]

Genetic substrate reduction therapy (GSRT) is another name for SRT, which is used to diminish the production of substrate by suppressing glucosylceramide, which is basically the rate-determining step of glucosylceramide synthesis. The first GSRT drug used for the management of GD1 was miglustat (developed in Switzerland). But the interesting thing is that miglustat inhibits glucosylceramide synthase, as well as being a nonselective inhibitor of glycosides, which leads to considerable side effects such as diarrhea and abdominal cramping. So, these complaints have led many victims to suspend the treatment. But the second drug, Eliglustat, which is far better than miglustat, but causes headache, joint pain, vomiting, stomachache, loose motion, discomfort, which is mild to moderate in severity, the use of these drugs has not been studied in conditions such as renal insufficiency and cardiac conditions. Moreover, these drugs are not prescribed in pregnancy and for lactating women.[35]

Gene therapy is a good candidate for LSDs, as, just like ERT, any restoration of even 10% of the residual activity can confer very substantial clinical benefit, and perhaps targeting a small number of cells is enough to compensate for the enzyme’s death, given the mechanism of M6P reuptake. In contrast, in some cases, due to the extreme rarity of the disease, there are no commercially available pharmacological treatments. Conversely, the disadvantages are many, and problems exist with gene therapy for LSDs. Gene safety remains a big concern in gene editing via viral vectors. Immunological responses against the produced enzyme and the development of cancer are possible if adenoviral and retroviral vectors are used. Gene therapy through intraventricular viral injection has been used in the mouse model for multiple sulfatase deficiency for the treatment of CNS-related symptoms, but this approach is still under rigorous investigation.[36]

Proteostasis regulators (PRs) are mainly regulated through lysosomal proteostasis, calcium homeostasis, the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway, the heat shock response (HSR), and the proteasomal degradation pathway. PRs are not restricted to lysosomal proteins; their non-specific action has generally influenced several proteostasis pathways. The main effects of nonspecific regulation are the induction of ERS and unfolded protein response (UPR), which can have consequences on cell viability or function. There are no currently licensed PRs for the treatment of LSDs. However, drug discovery in this space has revealed some interesting compounds that may provide an avenue for the development of new treatments that could enhance the advantage of pharmacological chaperone (PC) cure for certain diseases or, in the case of LSDs, ameliorate the impact of the relevant missense mutations.[37]

Future directions

Therapeutic strategies for the future of LSDs are focused on novel approaches to meet the challenges of current treatments. Innovation in genetic engineering, such as CRISPR gene-editing techniques and ribonucleic acid (RNA)-based therapeutics, presents possibilities of rectifying genetic flaws at their source. Key emphasis remains on modifying ERT, with better delivery systems and reduced immunogenicity while enhancing CNS targeting. Small-molecule chaperones and stem cell-based techniques hold promise for the improvement of lysosomal function and the restoration of enzyme activity. Avoidance of immune responses, improved blood-brain barrier penetration, and implementation of digital health technology for monitoring patients could be considered for future study. An active collaboration at the global level is needed to ensure reduced costs and improved accessibility for people requiring care, so that equity in care may be achieved as work on alleviating these rare genetic disorders continues.

Conclusion

LSDs are complex congenital disorders having colossal ramifications for health. Developments in treatment modalities, such as ERT, SRT, chaperone therapy, gene-editing techniques like CRISPR, proteostasis regulators, and HSCT, are frontiers of new therapeutic applications. Though these therapies have improved disease management and patient outcomes, significant hurdles such as CNS penetration, immune response-related issues, and high costs of treatment remain. Uninterrupted research, worldwide cooperation, and individualized focus are the need of the hour to conquer these hindrances and develop efficacious, affordable, and sustainable treatments for LSD patients. The convergence of novel therapies and advancements in gene and protein technologies presents a renewed hope for transformative improvements in dealing with these rare genetic diseases.

References

- Sun A. Lysosomal storage disease overview. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6(24):476.-476. doi:10.21037/atm.2018.11.39 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Platt FM, d’Azzo A, Davidson BL, Neufeld EF, Tifft CJ. Lysosomal storage diseases Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):27. doi:10.1038/s41572-018-0025-4 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Schröder B, Wrocklage C, Pan C, et al. Integral and associated lysosomal membrane proteins. Traffic. 2007;8(12):1676-1686. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00643.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wang RY, Bodamer OA, Watson MS, Wilcox WR; ACMG Work Group on Diagnostic Confirmation of Lysosomal Storage Diseases. Lysosomal storage diseases: diagnostic confirmation and management of presymptomatic individuals. Genet Med. 2011;13(5):457-484. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e318211a7e1 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Schultz ML, Tecedor L, Chang M, Davidson BL. Clarifying lysosomal storage diseases. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34(8):401-410. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2011.05.006 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Boustany RMN. Lysosomal storage diseases – The horizon expands. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(10):583-598. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2013.163 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Beck M. New aspects of LSD: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Inborn Errors Metab Screen. 2016;4. doi:10.1177/2326409816685736 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Annunziata I, Sano R, d’Azzo A. Mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs) and lysosomal storage diseases. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(3):328. doi:10.1038/s41419-017-0025-4 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Nagral A. Gaucher disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014;4(1):37-50. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2014.02.005 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Stirnemann J, Belmatoug N, Camou F, et al. A Review of Gaucher Disease Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation and Treatments. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(2):441. doi:10.3390/ijms18020441 PubMed | Crossref| Google Scholar

- Kohler L, Puertollano R, Raben N. Pompe Disease: From Basic Science to Therapy. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15(4):928-942. doi:10.1007/s13311-018-0655-y PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Taverna S, Cammarata G, Colomba P, et al. Pompe disease: pathogenesis, molecular genetics and diagnosis. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(15):15856-15874. doi:10.18632/aging.103794 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lerario S, Monti L, Ambrosetti I, et al. Fabry disease: a rare disorder calling for personalized medicine. Int Urol Nephrol. 2024;56(10):3161-3172. doi:10.1007/s11255-024-04042-4 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Fernández-Pereira C, San Millán-Tejado B, Gallardo-Gómez M, et al. Therapeutic Approaches in Lysosomal Storage Diseases. Biomolecules. 2021;11(12):1775. doi:10.3390/biom11121775 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Parenti G, Andria G, Ballabio A. Lysosomal storage diseases: From pathophysiology to therapy. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:471-486. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-122313-085916 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Best D. Rare monosaccharides and biologically active iminosugars from carbohydrate chirons. 2011. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.1619.6644 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Macauley SL, Sands MS. Promising CNS-directed enzyme replacement therapy for lysosomal storage diseases. Exp Neurol. 2009;218(1):5-8. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.03.040 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kuk MU, Lee YH, Kim JW, Hwang SY, Park JT, Park SC. Potential Treatment of Lysosomal Storage Disease through Modulation of the Mitochondrial-Lysosomal Axis. Cells. 2021;10(2):420. doi:10.3390/cells10020420 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Nakamura K, Hattori K, Endo F. Newborn screening for lysosomal storage disorders. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2011;157(1):63-71. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.30291 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Coutinho MF, Santos JI, Alves S. Less Is More: Substrate Reduction Therapy for Lysosomal Storage Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(7):1065 doi:10.3390/ijms17071065 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Parenti G, Andria G, Ballabio A. Lysosomal storage diseases: From pathophysiology to therapy. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:471-486. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-122313-085916 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Fernández-Pereira C, San Millán-Tejado B, Gallardo-Gómez M, et al. Therapeutic Approaches in Lysosomal Storage Diseases. Biomolecules. 2021;11(12):1775. doi:10.3390/biom11121775 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Biffi A. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy for storage disease: current and new indications. Mol Ther. 2017;25(5):1155-1162. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.025 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sariyar M, Schlünder I. Challenges and Legal Gaps of Genetic Profiling in the Era of Big Data. Front Big Data. 2019;2:40. doi:10.3389/fdata.2019.00040 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Parenti G, Medina DL, Ballabio A. The rapidly evolving view of lysosomal storage diseases. EMBO Mol Med. 2021;13(2):e12836. doi:10.15252/emmm.202012836 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Redman M, King A, Watson C, King D. What is CRISPR/Cas9? Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2016;101(4):213-215. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2016-310459 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Christensen C, Choy F. A prospective treatment option for lysosomal storage diseases: CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology for mutation correction in induced pluripotent stem cells. Diseases. 2017;5(1):6. doi:10.3390/diseases5010006 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mohamed FE, Al-Gazali L, Al-Jasmi F, Ali BR. Pharmaceutical Chaperones and Proteostasis Regulators in the Therapy of Lysosomal Storage Disorders: Current Perspective and Future Promises. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:448. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00448 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Placci M, Giannotti MI, Muro S. Polymer-based drug delivery systems under investigation for enzyme replacement and other therapies of lysosomal storage disorders. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2023;197:114683. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2022.114683 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Safary A, Khiavi MA, Mousavi R, Barar J, Rafi MA. Enzyme replacement therapies: What is the best option? BioImpacts. 2018;8(3):153-157. doi:10.15171/bi.2018.17 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Haneef SA, Doss CG. Personalized Pharmacoperones for Lysosomal Storage Disorder: Approach for Next-Generation Treatment. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2016;102:225-265. doi:10.1016/bs.apcsb.2015.10.001 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Parenti G, Pignata C, Vajro P, Salerno M. New strategies for the treatment of lysosomal storage diseases (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2013;31(1):11-20. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2012.1187 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Parenti G, Andria G, Valenzano KJ. Pharmacological chaperone therapy: Preclinical development, clinical translation, and prospects for the treatment of lysosomal storage disorders. Mol Ther. 2015;23(7):1138-1148. doi:10.1038/mt.2015.62 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rastall DPW, Amalfitano A. Recent advances in gene therapy for lysosomal storage disorders. Appl Clin Genet. 2015;8:157-169. doi:10.2147/TACG.S57682 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sohn YB, Yoo HW. Substrate reduction therapy as a new treatment option for patients with Gaucher disease type 1: A review of literatures. J Genet Med. 2016;13(2):59-64. doi:10.5734/jgm.2016.13.2.59 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Spampanato C, De Leonibus E, Dama P, et al. Efficacy of a combined intracerebral and systemic gene delivery approach for the treatment of a severe lysosomal storage disorder. Mol Ther. 2011;19(5):860-869. doi:10.1038/mt.2010.299 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Song W, Wang F, Savini M, et al. TFEB regulates lysosomal proteostasis. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(10):1994-2009. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddt052 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

No external support or assistance was received.

Funding

This literature review was self-funded. No external funding was received.

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Maida Noor

Department of Pharmacy

Quaid-I-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan

Email: assetocorsa123@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Fareeha Parveen

College of Pharmacy

University of Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan

Rehan Amjad

Department of Pharmacy

University of Lahore, Lahore, Pakistan

Eman Nasir

Department of Biotechnology

Quaid-I-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan

Authors Contributions

Fareeha Parveen conducted the literature search, drafted the initial sections of the manuscript, and organized the entire document. Maida Noor was responsible for the origination and supervision of the review and carried out a rigorous revision of the complete manuscript. Eman Nasir assisted with data extraction from the literature, formatted the figures, and contributed to refining the manuscript structure. Rehan Amjad reviewed and evaluated relevant studies, managed the referencing, and performed proofreading of the final version.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Guarantor

Maida Noor serves as the guarantor of the article and accepts full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of its content.

DOI

Cite this Article

Parveen F, Noor M, Nasir E, Amjad R. Emerging Therapeutic Strategies for Lysosomal Storage Diseases: Addressing the Challenges of Pharmacotherapy in Rare Genetic Diseases. medtigo J Pharmacol. 2025;2(2):e3061225. doi:10.63096/medtigo3061225 Crossref