Author Affiliations

Abstract

Delayed post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy (DPHL) is a rare complication of hypoxic brain injury, which can present with a wide spectrum of symptoms 1-4 weeks after the incident. The diagnosis is supported by the presence of white matter changes on the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). We present a 54-year-old Caucasian female with a 3-week history of opioid overdose and sexual trauma who presented to the hospital with symptoms of unresponsiveness, irritability, mobility issues, and aggressive and combative behavior for three days. Initially, substance abuse and infections were ruled out. A head computed tomography (CT) showed no acute findings. MRI of the brain without contrast & and T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (T2-FLAIR) without contrast showed extensive signal abnormalities throughout the white matter of bilateral cerebral hemispheres, which was suggestive of hypoxic brain injury. The onset of catatonia-like symptoms, along with imaging findings, supported the diagnosis of DPHL. The patient showed improvement after starting physical therapy and restarting the home dose of clonazepam. There are no standardized diagnostic criteria for DPHL, which makes it challenging for clinicians to diagnose. It is vital to keep DPHL in differential diagnosis, especially when there is a history of recent hypoxic injury, for optimal patient care.

Keywords

Catatonia, Delayed post-hypoxic encephalopathy, Delayed neurologic sequelae, Opioid overdose, Trauma.

Introduction

Delayed post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy, also known as Grinker’s myelopathy, is a rare and poorly understood complication that occurs after prolonged hypo-oxygenation. The condition is characterized by an initial latent period of no apparent symptoms followed by the development of white matter lesions and psychiatric and neurocognitive symptoms within 1-4 weeks of the initial event.[1] Patients can present with variable symptoms, including catatonia, parkinsonism, cognitive impairment, and psychiatric symptoms. Most of the cases are presented following hypoxic insults, such as opioid overdose, benzodiazepine overdose, carbon monoxide poisoning, cardiac arrest, strangulation, or hemorrhagic shock.[2]

The hallmark of DPHL is the presence of white matter changes on MRI. Most often, the white matter changes are centrum semiovale in the region but not necessary for diagnosing DPHL.[3] The pathophysiology of DPHL is complex and yet to be completely understood, but it is believed that there is delayed demyelination of cerebral white matter due to hypoxic-metabolic injury to oligodendrocytes.[4]

In this case report, we discuss the case of DPHL in a 54-year-old woman with a history of opioid overdose, sexual and physical trauma, and psychiatric comorbidities, highlighting the importance of considering this diagnosis in similar clinical scenarios.

Case Presentation

A 54-year-old Caucasian female with a past medical history of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depressive disorder (MDD), and bipolar I disorder (BD-1) presented to the emergency department with symptoms of catatonia. The patient’s caregiver reported a three-day history of unresponsiveness, impaired self-care, rigidity, combativeness, and intermittent aggression. Three weeks before this presentation, the patient had been hospitalized for an opioid overdose and physical/sexual assault. She received naloxone from emergency medical services at that time, which resulted in clinical improvement. Subsequent imaging at that time did not reveal any acute findings or evidence of hypoxic brain injury; after getting stable, the patient was discharged from the hospital.

On the initial presentation, the patient exhibited prolonged immobility and failed to initiate voluntary movements. She did not engage in conversation and appeared disconnected from her surroundings. The neurological exam revealed a pronounced left-sided response compared to the right for cranial nerve II. Examination of cranial nerves V, IX, XI, and XII was not feasible due to the patient’s lack of cooperation; the rest of the cranial nerves were unremarkable.

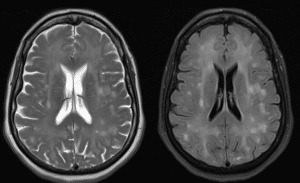

After ruling out infections and substance abuse, a head CT scan revealed no acute findings. Subsequently, an MRI of the brain with contrast was ordered to assess any structural abnormalities. The MRI revealed extensive FLAIR and T2 signal abnormality throughout the white matter of the bilateral cerebral hemisphere. Areas of restricted diffusion within the bilateral cerebral hemisphere were noted, indicative of hypoxic-ischemic injury supporting the diagnosis of DPHL. The pertinent images are shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1: MRI of Brain without contrast (Left) & T2 FLAIR MRI of Brain without contrast (Right)

Both show extensive signal abnormalities throughout the white matter of bilateral cerebral hemispheres, suggestive of hypoxic-ischaemic injury.

Case Management

Treatment for DPHL is mainly supportive. In this case, the patient was restarted on her previous psychiatric medications, fluoxetine 40mg and clonazepam 0.5mg, to manage the underlying psychiatric conditions. Additionally, physical therapy was also started. The patient showed improvement in her psychiatric symptoms after 3 days and was discharged from the hospital to continue outpatient physical therapy rehabilitation.

Discussion

The patient in this report presented with several features suggestive of catatonia, including immobility, negativism, posturing, and mutism, fulfilling the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5 criteria). Furthermore, with a history of substance abuse and the presence of other psychiatric conditions, catatonia was high on the differential diagnosis.[5,6] Psychiatric manifestations in the context of hypoxic brain injury can be diverse and may include altered consciousness, mood disturbances, and cognitive impairments. Catatonia and hypoxic brain injury are distinct entities and can occur simultaneously, but their coexistence is exceedingly rare.[7] In this case, due to the complex nature of the patient’s clinical presentation and MRI findings supporting the diagnosis of DPHL, catatonia was ruled out.

DPHL can present with a vast spectrum of clinical presentations depending on the area of the brain affected. Encephalopathy and cognitive decline are typically associated with diffuse T2-hyperintensities in the cerebral white matter, while catatonia-like symptoms such as akinetic mutism, psychomotor agitation, and combativeness are connected with basal ganglia and thalamic involvement.[8] Pathophysiology of DPHL is complex, but it is believed that Wallerian degeneration, adenosine triphosphate depletion, lipid peroxidation, inflammatory reaction, microglial proliferation, and delayed apoptosis of oligodendrocytes may play an imperative role in white matter injury. There is also a possibility of myelin sheath damage, causing delayed symptoms after a latent period of 1-4 weeks, as myelin secretion occurs every 19-22 days.[9]

Although there are no standardized diagnostic criteria for DPHL, an MRI brain is used to support the diagnosis of DPHL.[1,9] In this case, MRI of the brain without contrast and T2 FLAIR without contrast showed extensive signal abnormalities throughout the white matter of bilateral cerebral hemispheres.

The patient’s response to restarting clonazepam in this case is noteworthy. Clonazepam is a benzodiazepine with anticonvulsant and anxiolytic properties and has been utilized off-label for the treatment of catatonia in a few cases.[10] The gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic effects of clonazepam may contribute to the modulation of neurotransmitter systems and help alleviate catatonic symptoms.[10] The improvement observed in this case with clonazepam suggests its potential role in managing catatonic symptoms.

Conclusion

There are no standardized diagnostic criteria for DPHL, which makes it challenging for clinicians to diagnose and report similar cases. It is crucial to keep DPHL in differential diagnosis, especially when there is a history of recent hypoxic injury, to avoid delay in patient care.

References

- Shprecher D, Mehta L. The syndrome of delayed post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy. NeuroRehabilitation. 2010;26(1):65-72 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Katyal N, Narula N, George P, Nattanamai P, Newey CR, Beary JM. Delayed post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy: A case series and review of literature. Cureus. 2018;10(4):e2481. doi:10.7759/cureus.2481 PubMed | Crossref |

Google Scholar - Jillella D, Herrera L, Deligtisch A. A case of delayed post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy masquerading as a primary psychiatric disorder (P1.155). Neurology. 2017;88(16_Supplement):P1.155. doi:10.1212/WNL.88.16_supplement.P1.155 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Coppola C, Oliva M, Saracino D, et al. Delayed post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy with a peculiar autoantibody association. Neurol Clin Neurosci. 2019;8(2):86-88. doi:10.1111/ncn3.12358 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rogers JP, Pollak TA, Begum N, et al. Catatonia: Demographic, clinical and laboratory associations. Psychol Med. 2021;53(6):1-11. doi:10.1017/S0033291721004402 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wilcox JA, Reid Duffy P. The syndrome of catatonia. Behav Sci (Basel). 2015;5(4):576-588. doi:10.3390/bs5040576 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hamlin DW, Hussain N, Pathare A. Storms and silence: A case report of catatonia and paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity following cerebral hypoxia. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:473. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02878 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Srichawla BS, Garcia-Dominguez MA. Spectrum of delayed post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy syndrome: A systematic review. World J Clin Cases. 2024;12(29):6285-6301. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v12.i29.6285 PubMed | Crossref |

Google Scholar - Syal A, Gupta S, Gupta M, Jesrani G, Arya Y. Delayed post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy following barbiturate overdose. J Acute Dis. 2022;11(4):165-167. doi:10.4103/2221-6189.355328 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Agrawal AK, Das S, Jagadisha Tirthalli. Clonazepam in catatonia: Thinking beyond the boundary of lorazepam: A case report. Indian J Psychol Med. 2022;45(1):97-99. doi:10.1177/02537176221116265 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

Not reported

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Raza Ahmed

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science

Marshall University John C. Edwards School of Medicine, USA

Email: razaravian2014@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Scott Murphy, Ethan Leabhart, Staicy Mathew

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science

Marshall University John C. Edwards School of Medicine, USA

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Informed Consent

Documentation of written consent is not available for this case study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Raza A, Ethan L, Scott M, Staicy M. Delayed Post-Hypoxic Leukoencephalopathy Presenting with Catatonia Symptoms Sequelae of Opioid Overdose and Trauma. medtigo J Neurol Psychiatry. 2024;1(1):e3084118. doi:10.63096/medtigo3084118 Crossref