Author Affiliations

Abstract

This study investigates how exercise, lifestyle factors, and technology may assist hypertension (HTN). It focuses on measuring the impact of different types of exercise, their intensity and duration, hydration practices, social support, and the effectiveness of utilizing artificial intelligence (AI) devices for blood pressure monitoring. This cross-sectional study included 1002 individuals aged 30 to 70 who met strict inclusion criteria, such as suffering from HTN and taking their medication regularly. The data required was quantitative and qualitative, obtained through both primary and secondary sources. A questionnaire was used for primary data collection, and data were gathered from primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare facilities. Strength training and aerobic activities have a significant effect on lowering blood pressure (Cramer’s V = 0.961), with a strong correlation. Patients who exercise for over 60 minutes, five times a week, have significantly lower blood pressure (BP) (Cramer’s V = 0.838). The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, low in sodium and rich in fruits and vegetables, is also associated with reduced BP (p<0.0001). Adequate sleep and the use of AI devices in BP monitoring also contribute to better BP management (p<0.0001).

Conclusion: This study emphasizes the significance of regular aerobic activity, a balanced diet, and adequate sleep patterns in managing HTN. Furthermore, the employment of AI devices in BP monitoring, such as smartwatches, adds immensely to BP management and supports informed health decisions among individuals with HTN, highlighting its value.

Keywords

Hypertension, Exercise, Artificial intelligence technology, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diet, Physical activity, Blood pressure monitoring.

Introduction

Despite conflicting medical definitions, HTN is universally acknowledged as a substantial risk factor for a variety of health conditions.[1,2,3] HTN, or high blood pressure, is a medical condition in which the pressure in your blood vessels is too high (140/90 mmHg or higher). It is a widespread public health concern caused by fluctuations in blood pressure against arterial walls throughout the day.[4,5] HTN is classified as a silent killer by the World Health Organization (WHO) because it often shows no warning signs or symptoms.[6] According to the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA), HTN is diagnosed when a diastolic blood pressure of 80 mm Hg or higher and a systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or higher are present.[7] There are two types of HTN: primary HTN and secondary HTN. Primary HTN is a condition with an unknown cause, often attributed to genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors such as obesity, lack of physical activity, high salt intake, and alcohol consumption. The cause of primary HTN is unknown in 90-95% of cases.[8,9] The second type is Secondary HTN, refers to arterial HTN that has a recognized cause and can be controlled by addressing the underlying cause. Approximately 5-10% of hypertensive individuals are affected.[10,11] The main causes of secondary HTN involve renovascular HTN, parenchymal renal disease, and primary aldosteronism.

Worldwide, high blood pressure contributes significantly to morbidity and mortality, especially in low and middle-income countries (LMICs).[12,13] Approximately 1.28 billion people worldwide, 30-79 years old, suffer from HTN, with two-thirds living in low- and middle-income countries. 46% are unaware of their condition, and only 42% receive treatment. Merely 21% can keep it under control. HTN is a major cause of early mortality, and the global objective is to reduce its prevalence by 33% by 2030. In 2015, HTN accounted for 14% of all global deaths, greater than any other risk factor for cardiovascular mortality, including pneumonia and diarrhea. The primary cause was a systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or above.[14] A study conducted in northern Jordan on the Bedouin group revealed that over half (57.1%) of hypertensive patients who were aware of their diagnosis failed to control their high blood pressure, and half (47.5%) of hypertensive patients were not aware of their diagnosis.[15]

Given the importance of blood pressure as a key marker that guides clinical decision-making in acute and long-term care, accurate and consistent blood pressure measurement is essential.[16] Blood pressure measurement is normally taken at the brachial artery, but wrist and finger monitors are also available.[17] When measuring blood pressure, it’s important to record two values. The first value, systolic pressure, represents the peak arterial pressure during contraction. The second value, diastolic pressure, represents the minimum arterial pressure during diastole. The mean arterial pressure can be calculated using a specific formula based on the systolic and diastolic pressures. Another method for measuring blood pressure is called automated office BP (AOBP).[16] This method is more aligned with ambulatory-awake blood pressure measurements, which decreases the likelihood of white-coat HTN. In some countries, 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure readings are considered the best way to diagnose HTN as they provide a more accurate reflection of clinical outcomes.[17] The traditional method of measuring blood pressure involves using a sphygmomanometer, which is a cuff inflated around the arm and connected to a pressure gauge. This method relies on listening to Korotkoff sounds. Alternatively, automated systems can measure blood pressure by detecting oscillations in blood flow as the cuff is deflated. Automated systems are beneficial because they require minimal user knowledge, making them suitable for non-medical use. For the most precise blood pressure measurements, an invasive probe inserted directly into an artery can be used, but this method is typically reserved for critical care or surgical settings.[16]

High blood pressure is linked to an increased risk of ischemic heart disease, heart failure, chronic renal disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease (PAD), dementia, cognitive impairment, and cardiovascular mortality.[18] HTN affects around 80-85% of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), with more severe glomerular disorders having a greater prevalence of HTN. Previous research has found that HTN raises the incidence of new or recurring cardiovascular (CV) events in people with stage 2-3 CKD. According to reports, high blood pressure is a significant independent risk factor for ESRD.[19] Also, high blood pressure is the primary modifiable risk factor for stroke, showing a strong, direct, linear, and continuous correlation between blood pressure and the likelihood of experiencing a stroke.[20] HTN affects various parts of the eye, leading to a series of retinal microvascular abnormalities known as hypertensive retinopathy.[21] Uncontrolled HTN is a major risk factor for vascular cognitive impairment and late-life dementia, since it compromises the blood-brain barrier, increases neuroinflammation, and may contribute to amyloid deposition and Alzheimer’s pathology.[22] The objective of this study is to identify the key factors contributing to HTN and to understand the effects of regular exercise and a healthy diet on improving blood pressure. Additionally, investigate the most likely complications and comorbidities of HTN.

Methodology

In this study, the impact of various factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity, anxiety, and depression on patients with HTN in Jordan was investigated. This study was conducted in strict accordance with the ethical standards established by the hospital’s research committee, adhering to the principles outlined in the 1964 declaration of helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The research protocol was rigorously reviewed and granted approval by the hospital’s research committee institutional review board (IRB/2024/4713). Additional approval for the research establishment and data collection was obtained from the head of the nephrology department, under whose supervision all data were collected.

The approval from the head department was contingent on the following conditions: Full compliance with the general policy of the hospital’s human research committee, strict confidentiality of all participant information, ensuring that data is used solely for scientific research purposes, mandatory informed consent from all participants prior to their involvement, prompt reporting of any modifications or unforeseen developments during the research to the head department. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were thoroughly briefed on the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Participants were reassured of their right to withdraw from the study at any point without repercussions, ensuring their autonomy and protection.

A questionnaire was utilized for primary data collection, and data were gathered through patient interviews. Following a systematic review of the findings, A thorough review of existing research and literature was carried out in preparation for secondary data collecting. The relevant data will be carefully reviewed to ensure that the findings are well-informed and reliable. Regarding the questionnaire, which was designed to collect data from patients with HTN on antihypertensive medication, it aimed to gather data from patients by answering the questions in the form when interviewing them.

During the interview, the following questions were asked about the patient: age, gender, type of HTN, the cause of HTN, since when diagnosed with HTN, complications and comorbidities associated with HTN, The type of antihypertensive medication, weight, if patient suffer from overweight, obesity, or comorbid obesity, if the patients smoke or not, if patients drink alcohol or not, if the patients suffered from anxiety or depression, regular BP check-ups, using of herbal remedies in treatment, do you do regular exercise? (yes or no response option): similar questions, whether the patient answers yes or no, are: baseline blood pressure, type of food, the amount of salts in diet, and duration of sleep over night, if the patients answer no: the reason why patients don’t do exercise, if the patients answer yes, the questions are: type of exercise, intensity of exercise, duration and frequency of exercise, type of environment when doing exercises, have a supportive network of family, friends, or a community that can encourage adherence to an exercise program and improve outcomes, and they think it’s beneficial? drink adequate water after or during exercise. Using a smartwatch or any app to detect BP, if they think the use of technology in detecting BP is beneficial, and if patients support the app that is supported by AI to enhance BP measurement and make them make healthy lifestyle choices.

Regarding the interviews with the patients, interviews were scheduled in primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare facilities. Following the end of data collection, the data will be clarified regarding specific parameters of inclusion and exclusion criteria to define the study population and enhance validity. The inclusion criteria included patients diagnosed with HTN, despite having primary or secondary HTN, undergoing treatment, and aged of more than 30 years old and less than 70 years old, regularly taking hypertensive medications, and patients, despite doing exercise or not. The exclusion criteria included patients who weren’t diagnosed with HTN, patients with HTN who don’t take medications regularly, and patients less than 30 years old or older than 70 years old.

Following the end of the data collection, 1002 responses in all were obtained. Then, the data was cleaned to make sure that each aspect of it satisfied the inclusion criteria and that none of them did not. The data was then imported into the SPSS software to begin the analysis.

Results

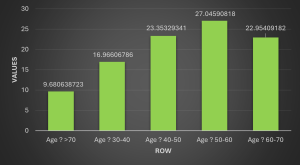

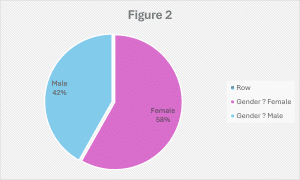

General demographic results: The study involved 1002 patients who all met the inclusion criteria. It offers a detailed analysis of the demographic, clinical, and social characteristics that are associated with HTN among the participants. The data indicates that 27.0% of the individuals fall within the 50–60-year age range, with significant representation from the 40-50 years age group (23.4%) and the 60-70 years age group (23.0%). A smaller but notable portion of participants were either younger, 30-40 years (17.0%), or older than 70 years (9.7%). In terms of gender distribution, 58.2% of the cohort was female, while 41.8% was male.

Participants were diagnosed with HTN, with primary HTN accounting for 52.8% and secondary HTN for 47.2% of the cases. Idiopathic HTN was the most common subtype, accounting for 60.0% of cases. Genetic predispositions, such as polycystic kidney disease, were found in 13.9% of participants, while primary aldosteronism was present in 10.2% of cases. Most participants had been diagnosed relatively recently, with 54.1% having received their diagnosis within the past decade.

The variety of treatments for HTN in this group was diverse. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors were the most used medication (31.2%), followed using ACE inhibitors (ACEI) in combination with diuretics (22.2%). The body mass index (BMI) profile of the group indicates a high prevalence of obesity, with 44.7% classified as obese.

Social patterns indicate that 53.6% of participants are current smokers, and 21.3% consume alcohol. Mental health is also a concern, with 49.2% of participants reporting a history of anxiety or depression. Regular blood pressure monitoring is prevalent, with 39.2% checking weekly. However, 12.6% do not engage in regular monitoring.

Of the participants, 47.7% used herbal remedies to treat HTN. However, 60.6% did not believe that herbal remedies were more effective than conventional medication, and 66.8% preferred standard treatments over herbal options. In terms of physical activity, 52.9% reported engaging in regular exercise, while 47.1% did not participate in regular physical activity.

| Table 1 | Count | Column N % | |

| Age? | >70 | 97 | 9.7% |

| 30-40 | 170 | 17.0% | |

| 40-50 | 234 | 23.4% | |

| 50-60 | 271 | 27.0% | |

| 60-70 | 230 | 23.0% | |

| Age variations (mean=3, median=3, Standard deviation (SD)=1) | |||

| Gender? | Female | 583 | 58.2% |

| Male | 419 | 41.8% | |

| Type of HTN? | Primary | 529 | 52.8% |

| Secondary | 473 | 47.2% | |

| The cause of HTN? | chronic kidney disease | 18 | 1.8% |

| coarctation of the aorta | 13 | 1.3% | |

| Cushing’s syndrome | 51 | 5.1% | |

| Genetics (polycystic kidney disease) | 139 | 13.9% | |

| Idiopathic | 601 | 60.0% | |

| Pheochromocytoma | 1 | 0.1% | |

| primary aldosteronism | 102 | 10.2% | |

| Renovascular HTN | 51 | 5.1% | |

| thyroid disorders | 26 | 2.6% | |

| Since when you are diagnosed with HTN? | 10 -20 years | 355 | 35.4% |

| Less than 10 years | 542 | 54.1% | |

| More than 20 years | 105 | 10.5% | |

| The type of Antihypertensive medication you take? | ACEI | 313 | 31.2% |

| ACEI, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) | 9 | 0.9% | |

| ACEI, ARB, Diuretics | 13 | 1.3% | |

| ACEI, Beta-blocker (BB) | 4 | 0.4% | |

| ACEI, BB, Diuretics | 11 | 1.1% | |

| ACEI, calcium channel blocker (CCB) | 1 | 0.1% | |

| ACEI, CCB, BB, Diuretics | 3 | 0.3% | |

| ACEI, CCB, Diuretics | 7 | 0.7% | |

| ACEI, Diuretics | 222 | 22.2% | |

| ARB | 190 | 19.0% | |

| ARB, BB | 3 | 0.3% | |

| ARB, BB, Diuretics | 3 | 0.3% | |

| ARB, CCB | 3 | 0.3% | |

| ARB, CCB, Diuretics | 2 | 0.2% | |

| ARB, Diuretics | 25 | 2.5% | |

| BB | 12 | 1.2% | |

| BB, Diuretics | 1 | 0.1% | |

| CCB | 63 | 6.3% | |

| CCB, BB | 3 | 0.3% | |

| CCB, BB, diuretics | 1 | 0.1% | |

| CCB, diuretics | 11 | 1.1% | |

| Diuretics | 102 | 10.2% | |

| Regarding BMI your Weight is considered as? | Morbid obesity | 117 | 11.7% |

| Normal BMI | 116 | 11.6% | |

| Obese | 448 | 44.7% | |

| Overweight | 321 | 32.0% | |

| Do you smoke? | Ex- smoker | 88 | 8.8% |

| No | 377 | 37.6% | |

| Yes | 537 | 53.6% | |

| Do you drink Alcohol? | No | 789 | 78.7% |

| Yes | 213 | 21.3% | |

| Have you ever suffered from anxiety or depression? | No | 509 | 50.8% |

| Yes | 493 | 49.2% | |

| Do you do a regular BP checkup? | No, I don’t | 126 | 12.6% |

| Yes, daily | 177 | 17.7% | |

| Yes, monthly | 306 | 30.5% | |

| Yes, weekly | 393 | 39.2% | |

| Using of herbal Remedy in treatment? (Have you ever used herbal Remedy in treatment ?) | No | 524 | 52.3% |

| Yes | 478 | 47.7% | |

| Using of herbal Remedy in treatment? (Do you think that herbal remedy is more beneficial than medication?) | No | 607 | 60.6% |

| Yes | 395 | 39.4% | |

| Using of herbal Remedy in treatment? (Do you prefer using herbal remedy more than medications ?) | No | 669 | 66.8% |

| Yes | 333 | 33.2% | |

| Do you do a regular exercise ? | No | 472 | 47.1% |

| Yes | 530 | 52.9% | |

The study has revealed a range of complications and comorbidities associated with HTN. The primary complications include heart disease (such as coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), affecting 13.6% of patients. Kidney damage (nephropathy) impacts 10.2% of patients, while eye damage (retinopathy) was reported in 8.5% of cases. In terms of comorbidities, the most prevalent combination was diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia, affecting 10.5% of participants, followed by a combination of diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and obesity, noted in 10.1% of cases. Mental health disorders were also found to be significant comorbidities, present in 8.6% of cases.

| Table 2 | Count | Column N % | |

| What complications you suffered from HTN? | Aneurysms | 3 | 0.3% |

| Aneurysms, metabolic syndrome | 72 | 7.2% | |

| cognitive impairment and dementia | 3 | 0.3% | |

| cognitive impairment and dementia, metabolic syndrome | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Eye damage (retinopathy) | 37 | 3.7% | |

| Eye damage (retinopathy), cognitive impairment and dementia | 3 | 0.3% | |

| Eye damage (retinopathy), cognitive impairment and dementia, metabolic syndrome | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Eye damage (retinopathy), metabolic syndrome | 3 | 0.3% | |

| Eye damage (retinopathy), no complications | 85 | 8.5% | |

| Eye damage (retinopathy), PAD | 8 | 0.8% | |

| Eye damage (retinopathy), PAD, Aneurysms | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Eye damage (retinopathy), PAD, cognitive impairment and dementia | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Eye damage (retinopathy), PAD, cognitive impairment and dementia, metabolic syndrome | 3 | 0.3% | |

| Eye damage (retinopathy), PAD, metabolic syndrome | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias) | 136 | 13.6% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), aneurysms, metabolic syndrome | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), cognitive impairment and dementia | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), eye damage (retinopathy) | 31 | 3.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), eye damage (retinopathy), cognitive impairment and dementia, metabolic syndrome | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), eye damage (retinopathy), metabolic syndrome | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), eye damage (retinopathy), PAD | 9 | 0.9% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), eye damage (retinopathy), PAD, cognitive impairment and dementia | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), eye damage (retinopathy), PAD, cognitive impairment and dementia, metabolic syndrome | 3 | 0.3% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), eye damage (retinopathy), PAD, metabolic syndrome | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), kidney damage (nephropathy) | 13 | 1.3% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), kidney damage (nephropathy), cognitive impairment and dementia, metabolic syndrome | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), kidney damage (nephropathy), eye damage (retinopathy) | 3 | 0.3% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), kidney damage (nephropathy), eye damage (retinopathy), metabolic syndrome | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), kidney damage (nephropathy), eye damage (retinopathy), PAD, cognitive impairment and dementia | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), kidney damage (nephropathy), metabolic syndrome | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), kidney damage (nephropathy), PAD | 7 | 0.7% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), kidney damage (nephropathy), PAD, aneurysms | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), kidney damage (nephropathy), PAD, metabolic syndrome | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), metabolic syndrome | 7 | 0.7% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), no complications | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), PAD | 9 | 0.9% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), PAD, cognitive impairment and dementia | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), PAD, cognitive impairment and dementia, metabolic syndrome | 4 | 0.4% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), PAD, metabolic syndrome | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), stroke (cerebrovascular accident (CVA)) | 21 | 2.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), stroke (CVA), aneurysms, metabolic syndrome | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), stroke (CVA), eye damage (retinopathy) | 6 | 0.6% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), stroke (CVA), eye damage (retinopathy), cognitive impairment and dementia, metabolic syndrome | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), stroke (CVA), eye damage (retinopathy), PAD, cognitive impairment and dementia, metabolic syndrome | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), stroke (CVA), kidney damage (nephropathy) | 5 | 0.5% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), stroke (CVA), kidney damage (nephropathy), cognitive impairment and dementia, metabolic syndrome | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), stroke (CVA), kidney damage (nephropathy), eye damage (retinopathy) | 6 | 0.6% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), stroke (CVA), kidney damage (nephropathy), eye damage (retinopathy), PAD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), stroke (CVA), kidney damage (nephropathy), eye damage (retinopathy), PAD, Metabolic syndrome | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), stroke (CVA), kidney damage (nephropathy), PAD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), stroke (CVA), PAD | 4 | 0.4% | |

| Heart disease (coronary artery disease, heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy, and arrhythmias), stroke (CVA), PAD, aneurysms | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Kidney damage (nephropathy) | 65 | 6.5% | |

| Kidney damage (nephropathy), cognitive impairment and dementia | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Kidney damage (nephropathy), eye damage (retinopathy) | 102 | 10.2% | |

| Kidney damage (nephropathy), eye damage (retinopathy), cognitive impairment and dementia, metabolic syndrome | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Kidney damage (nephropathy), eye damage (retinopathy), metabolic syndrome | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Kidney damage (nephropathy), metabolic syndrome | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Kidney damage (nephropathy), PAD | 5 | 0.5% | |

| Kidney damage (nephropathy), PAD, aneurysms | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Kidney damage (nephropathy), PAD, cognitive impairment and dementia | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Metabolic syndrome | 59 | 5.9% | |

| No complications | 136 | 13.6% | |

| PAD | 11 | 1.1% | |

| PAD, Aneurysms | 1 | 0.1% | |

| PAD, cognitive impairment and dementia. | 3 | 0.3% | |

| PAD, metabolic syndrome | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Stroke (CVA) | 13 | 1.3% | |

| Stroke (CVA), Aneurysms | 60 | 6.0% | |

| Stroke (CVA), cognitive impairment and dementia | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Stroke (CVA), cognitive impairment and dementia, metabolic syndrome | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Stroke (CVA), eye damage (retinopathy) | 7 | 0.7% | |

| Stroke (CVA), eye damage (retinopathy), PAD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Stroke (CVA), kidney damage (nephropathy) | 3 | 0.3% | |

| Stroke (CVA), kidney damage (nephropathy), eye damage (retinopathy) | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Stroke (CVA), kidney damage (nephropathy), PAD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Stroke (CVA), metabolic syndrome | 3 | 0.3% | |

| Stroke (CVA), PAD | 3 | 0.3% | |

| Stroke (CVA), PAD, cognitive impairment and dementia. | 1 | 0.1% | |

| What other comorbidities associated with HTN? | Cardiovascular diseases | 71 | 7.1% |

| Cardiovascular diseases, no comorbidities | 1 | 0.1% | |

| CKD | 5 | 0.5% | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 79 | 7.9% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases | 7 | 0.7% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, CKD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, OSA, CKD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, OSA, PAD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, PAD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, PAD, mental health disorders | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, CKD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia | 105 | 10.5% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular diseases | 9 | 0.9% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular diseases, CKD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular diseases, OSA | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular diseases, OSA, CKD, PAD, mental health disorders | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular diseases, OSA, PAD, mental health disorders | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular diseases, PAD | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, CKD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, mental health disorders | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity | 101 | 10.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, cardiovascular diseases | 3 | 0.3% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, CKD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, PAD | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, CKD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, mental health disorders | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, OSA | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, OSA, mental health disorders | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, PAD, mental health disorders | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, OSA | 3 | 0.3% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, OSA, CKD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, OSA, mental health disorders | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, OSA, PAD, mental health disorders | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, PAD | 4 | 0.4% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, PAD, mental health disorders | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, mental health disorders | 3 | 0.3% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, obesity | 13 | 1.3% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, obesity, cardiovascular diseases | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, obesity, CKD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, obesity, mental health disorders | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, obesity, OSA | 4 | 0.4% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, obesity, OSA, mental health disorders | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, obesity, PAD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, OSA | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, OSA, mental health disorders | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, PAD | 5 | 0.5% | |

| Diabetes mellitus, PAD, mental health disorders | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Dyslipidemia | 29 | 2.9% | |

| Dyslipidemia, cardiovascular diseases | 7 | 0.7% | |

| Dyslipidemia, cardiovascular diseases, OSA | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Dyslipidemia, cardiovascular diseases, PAD | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Dyslipidemia, mental health disorders | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Dyslipidemia, no comorbidities | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Dyslipidemia, obesity | 6 | 0.6% | |

| Dyslipidemia, obesity, cardiovascular diseases | 3 | 0.3% | |

| Dyslipidemia, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, OSA | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Dyslipidemia, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, OSA, PAD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Dyslipidemia, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, PAD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Dyslipidemia, obesity, OSA | 99 | 9.9% | |

| Dyslipidemia, OSA | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Dyslipidemia, OSA, PAD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Mental health disorders | 86 | 8.6% | |

| No comorbidities | 106 | 10.6% | |

| Obesity | 62 | 6.2% | |

| Obesity, cardiovascular diseases | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Obesity, cardiovascular diseases, OSA, PAD, mental health disorders | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Obesity, cardiovascular diseases, PAD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Obesity, CKD | 50 | 5.0% | |

| Obesity, OSA | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Obesity, OSA, PAD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Obesity, OSA, PAD, mental health disorders | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Obesity, PAD | 1 | 0.1% | |

| OSA | 2 | 0.2% | |

| OSA, mental health disorders | 2 | 0.2% | |

| OSA, PAD | 2 | 0.2% | |

| OSA, PAD, mental health disorders | 1 | 0.1% | |

| PAD | 6 | 0.6% | |

| PAD, mental health disorders | 71 | 7.1% | |

In another point, the study aimed to evaluate various health and exercise-related factors among participants. It was divided into two categories based on patients’ adherence to exercise. On one side, individuals who exercise regularly had an average blood pressure of 135/87. Regarding exercise types, 37.5% of patients were engaged in aerobic exercises such as walking and cycling. Most participants (60.6%) exercised 3-5 days a week, with 22.4% exercising for more than 30 but less than 60 minutes per session. Among those who exercised more than 5 days a week, 28.3% engaged in sessions lasting more than 60 minutes, the highest duration reported.

Results regarding dietary habits indicated that 24.2% of the participants followed the DASH diet, which is characterized by a low salt intake and consumption of fruits and vegetables. Most participants (29.6%) reported consuming between 1,500 and 2,300 mg of salt daily, making it the most common salt intake range. Regarding exercise conditions, 30.3% of the participants preferred warm environments with temperatures ranging from 15°C-30°C. Additionally, 33% of patients highlighted the importance of having a supportive network in their journey. In terms of sleep, 29.7% of participants reported getting 6-9 hours of sleep per night. Adequate hydration during or after exercise was achieved by 35.2% of the participants.

According to the study, 28.1% of participants had not used smart technology for blood pressure monitoring, while 22.4% reported finding such technology beneficial. Furthermore, 42% of the participants expressed support for the use of an AI app to improve blood pressure measurement and encourage healthy lifestyle choices.

| Table 3: BP in Patients who do exercise | Column N % | Count | |

| Systolic BP (mean=135, median=135, SD=16) | 100.0% | ||

| Diastolic BP (mean=87, median=85, SD=8) | 100.0% | ||

| Type of exercise? | Aerobic exercise (activities like walking, jogging, cycling, swimming, and dancing) | 37.5% | 376 |

| Strength training (resistance exercises such as weightlifting, bodyweight exercises) | 15.4% | 154 | |

| Intensity of Exercise VAR | Intense | 13.3% | 133 |

| Mild | 8.8% | 88 | |

| Moderate | 26.7% | 268 | |

| Very Mild | 4.1% | 41 | |

| Duration and frequency of Exercise? (Less than 3 days a week) | Less than 30 min | 12.6% | 126 |

| Less than 30 min, more than 30 but less than 60 min | 0.3% | 3 | |

| Less than 30 min, more than 60 min | 0.1% | 1 | |

| More than 30 but less than 60 min | 16.2% | 162 | |

| More than 60 min | 10.7% | 107 | |

| Duration and frequency of Exercise? (3-5 days a week) | Less than 30 min | 16.5% | 165 |

| Less than 30 min, more than 30 but less than 60 min | 0.2% | 2 | |

| More than 30 but less than 60 min | 22.4% | 224 | |

| More than 60 min | 0.4% | 4 | |

| Duration and frequency of Exercise? (More than 5 days a week) | Less than 30 min | 12.8% | 128 |

| Less than 30 min, more than 30 but less than 60 min | 0.6% | 6 | |

| Less than 30 min, more than 60 min | 0.5% | 5 | |

| More than 30 but less than 60 min | 3.6% | 36 | |

| More than 60 min | 28.3% | 284 | |

| What type of food you eat? | A mix between DASH diet and unhealthy food | 23.2% | 232 |

| DASH diet (low in salt and rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy, and lean protein). | 24.2% | 242 | |

| Unhealthy food (fast food and junk food) | 5.6% | 56 | |

| The amount of salt in your Diet? | 1,500 mg – 2,300 mg | 29.6% | 297 |

| Less than 1,500 mg | 21.2% | 212 | |

| More than 2,300 mg | 0.3% | 3 | |

| Type of Environment when doing exercise? | Cool to cold, with temperatures ranging from 5°C to 15°C | 0.6% | 6 |

| Hot and dry | 5.5% | 55 | |

| Mild and pleasant, with temperatures ranging from 10°C to 25°C | 16.5% | 165 | |

| Warm and pleasant, with temperatures ranging from 15°C to 30°C | 30.3% | 304 | |

| Do you have a supportive network of family, friends, or a community that can encourage adherence to an exercise program and improve outcomes and do you think its beneficial? | No, I don’t | 3.5% | 35 |

| Yes, and I don’t think its beneficial | 16.4% | 164 | |

| Yes, and I think its beneficial | 33.0% | 331 | |

| How many hours you sleep overnight? | 6-9 hours | 29.7% | 298 |

| Less than 6 hours | 22.5% | 225 | |

| More than 9 hours | 0.7% | 7 | |

| Do you drink adequate water after or during exercise? | No | 17.7% | 177 |

| Yes | 35.2% | 353 | |

| Have you ever used Smart watch or any App to detect Your Bp? | No | 28.1% | 282 |

| Yes | 23.0% | 230 | |

| Do you think its beneficial to use technology in detecting BP? | I don’t use technology in detecting BP? | 26.8% | 269 |

| No | 1.9% | 19 | |

| Yes | 22.4% | 224 | |

| Do you support making app that is supported by AI to enhance your BP measurement and make for you a healthy lifestyle choice? | No | 9.1% | 91 |

| Yes | 42.0% | 421 | |

On the other hand, the study examined various health-related factors among individuals who do not engage in regular exercise, accounting for around 52.9% of all participants. The data revealed a mean systolic blood pressure of 158 mmHg and a mean diastolic blood pressure of 93 mmHg among these individuals, indicating a significant elevation in blood pressure compared to individuals who exercise regularly.

In terms of dietary habits, the most common pattern observed was a combination of the DASH diet and unhealthy foods, accounting for 20.2% of patients. The intake of salt varied, with the most frequent category being less than 1,500 mg per day, reported by 18.3% of these individuals.

Regarding sleep patterns, 31.9% reported they slept between 6-9 hours per night, which was the most common sleep duration. The reasons for not engaging in exercise were primarily physical limitations (19.3%), followed by a lack of motivation (14.3%) and a lack of time (12.9%).

| Table 4: BP in Patients who don’t do exercise | Count | Column N % | |

| Systolic BP (mean=158, median=150, SD=24) | |||

| Diastolic BP (mean=93, median=90, SD=16) | |||

| What type of food you eat? | A mix between DASH diet and unhealthy food | 202 | 20.2% |

| DASH diet (low in salt and rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy, and lean protein) | 132 | 13.2% | |

| Unhealthy food (fast food and junk food) | 138 | 13.8% | |

| The amount of salt in your Diet? | 1,500 mg – 2,300 mg | 126 | 12.6% |

| Less than 1,500 mg | 183 | 18.3% | |

| More than 2,300 mg | 154 | 15.4% | |

| How many hours you sleep overnight? | 6-9 hours | 320 | 31.9% |

| Less than 6 hours | 144 | 14.4% | |

| More than 9 hours | 8 | 0.8% | |

| The reason why you don’t do exercise? | Lack of motivation | 143 | 14.3% |

| Lack of time | 129 | 12.9% | |

| Others | 7 | 0.7% | |

| Physical limitations | 193 | 19.3% | |

The analysis shows strong connections between different lifestyle factors (BMI, smoking, and alcohol consumption) and baseline blood pressure. The Chi-Square tests reveal statistically significant relationships for each factor (BMI: Pearson Chi-Square = 1121.831, p<0.001; smoking status: Pearson Chi-Square = 1006.174, p<0.001; alcohol consumption: Pearson Chi-Square = 667.528, p<0.001). Higher BMI categories, particularly morbid obesity, are linked to higher blood pressure readings. Smokers and individuals who consume alcohol also exhibit noticeable differences in blood pressure compared to non-smokers and non-drinkers. These findings emphasize the impact of these lifestyle factors on blood pressure and suggest that targeted interventions addressing BMI, smoking, and alcohol use could be beneficial for managing HTN. Moreover, “Chi-square tests were conducted to analyze the relationship between various factors, such as history of anxiety or depression, frequency of blood pressure check-ups, use of herbal remedies, regular exercise, and baseline blood pressure readings. The results show significant associations with baseline blood pressure, with Pearson Chi-Square values ranging from 443.135 to 1002.000 (all p<0.001). For example, individuals with a history of anxiety or depression exhibit different baseline blood pressure distributions with higher Bp readings compared to those without such a history. However, individuals with regular exercise, monitoring blood pressure, and utilizing herbal remedies can experience significant variations in baseline readings, leading to lower BP levels. The high Cramer’s V values, ranging from 0.646 to 1.000, suggest a strong association between these lifestyle factors and blood pressure levels. These findings emphasize the importance of considering mental health history, lifestyle choices, and adherence to regular health monitoring when evaluating blood pressure and its management.

Parameters affecting BP in patients doing exercise: The analysis of the relationship between exercise type, intensity, and duration with baseline blood pressure (mean BP=135/87) reveals significant associations. The chi-square tests indicate a strong correlation between these variables and blood pressure measurements (p<0.0001 in all cases). Specifically, for exercise types, aerobic exercise shows a pronounced correlation with blood pressure, with a Cramer’s V of 0.961, suggesting a very strong relationship. Strength training, with a Cramer’s V of 0.811, also demonstrates a notable association. Cross-tabulation shows that individuals engaging in aerobic activities predominantly have lower baseline blood pressures (mean BP=135/87) compared to those who do not exercise or engage in strength training. The analysis also indicates a strong correlation between higher exercise intensity and lower blood pressure. The chi-square result (Cramer’s V of 0.811) confirms that individuals who engage in more intensive exercise, particularly for over 60 minutes per session, generally have lower blood pressure. Moreover, both the duration and frequency of exercise are significant factors, with individuals who exercise more than five days a week or for over 60 minutes having a stronger association with lower blood pressure levels (mean BP=135/87) (Cramer’s V of 0.838). Additionally, exercising in warmer and more pleasant conditions is linked to better blood pressure outcomes.

The analysis shows that individuals who follow a DASH diet, which includes low salt intake and high consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy, and lean proteins, generally have lower baseline blood pressures (mean BP=135/87) compared to those who have a mix of DASH and unhealthy foods or those who primarily consume unhealthy foods like fast food and junk food (mean BP=158/93). Additionally, the chi-square tests indicate a significant association between diet and blood pressure levels, demonstrating a noticeable difference in blood pressure readings among different dietary groups (Chi-Square value: 2690.011, p<0.001). Similarly, the amount of salt consumed strongly correlates with blood pressure, as higher salt intake is associated with elevated blood pressure readings (Chi-Square value: 2144.215, p<0.001). Moreover, having a supportive network of family, friends, or community for encouragement in maintaining an exercise regimen significantly impacts blood pressure management, highlighting the importance of social support in health outcomes (Chi-Square value: 3008.017, p<0.001).

Certain parameters were tested, such as sleep duration, water intake during exercise, use of smartwatches (AI) or apps for blood pressure monitoring, and the perceived benefits of using technology for blood pressure detection.

For sleep duration, the chi-square test indicates a significant association with baseline blood pressure (χ² = 1919.019, p< 0.0001), with Cramer’s V showing a strong effect size of 0.799. This suggests that variations in sleep duration are significantly related to different blood pressure levels. Patients who sleep 6-9 hours have lower BP values (mean BP=135/87) compared to those who sleep less than 6 hours.

Regarding water intake during exercise, the chi-square test results (χ² = 1881.278, p<0.0001) and Cramer’s V of 0.969 indicate a very strong relationship between adequate water consumption and a lower baseline blood pressure.

The use of AI such as smartwatches or apps for monitoring blood pressure also shows a significant association (χ² = 1814.341, p<0.0001) with a Cramer’s V=0.952, indicating that the use of technology is strongly related to different blood pressure levels.

Finally, the study revealed a strong correlation between the perceived benefits of utilizing technology for blood pressure detection (χ² = 2293.785, p<0.0001, Cramer’s V=0.939) and lower baseline blood pressure. This indicates that individuals’ beliefs about the effectiveness of technology in monitoring blood pressure align closely with their actual blood pressure readings.

Parameters affecting BP in patients who don’t exercise: The data explores the relationship between baseline blood pressure and dietary habits, specifically focusing on food types and salt intake. It shows a significant association between blood pressure and diet, as indicated by a high Pearson Chi-Square value (2477.864, p< 0.001 for food types and 2450.783, p<0.001 for salt intake). The analysis reveals that individuals consuming a low-salt diet, like the DASH diet, generally have lower blood pressure readings. Conversely, those consuming unhealthy food or high-salt diets tend to have higher blood pressure. For instance, individuals with blood pressure readings of 200/110 and above often consume diets high in salt (more than 2,300 mg) and unhealthy foods, whereas those adhering to the DASH diet report lower blood pressure values, such as 124/73 or 130/80. The data also indicates that most participants have mixed diets, combining healthy and unhealthy eating patterns. The strong and statistically significant association between diet, salt intake, and baseline blood pressure is supported by the high Cramer’s V values (0.908 for food type and 0.896 for salt intake) and the chi-squared tests.

The analysis of the correlation between baseline blood pressure (BP) and two variables, hours of sleep overnight and BMI classification, shows significant relationships in both cases. The Pearson Chi-Square test for the association between hours of sleep overnight and BP yielded a value of 2060.626 (degree of freedom (df) = 423, p<0.001), indicating a strong association. The Cramer’s V value of 0.828 further suggests a substantial effect size. The data indicated that most individuals with baseline BP readings clustered in the range of 130/80 to 140/90 were more likely to sleep for 6-9 hours. Those with extreme BP readings (e.g., 200/110 or 250/170) were less consistently associated with any specific sleep duration. Regarding BMI, the analysis also found a significant relationship (Chi-Square = 1058.686, df = 423, p<0.001) with a Cramer’s V of 0.514, indicating a moderate effect size. Individuals classified as obese or morbidly obese due to not doing exercise were more likely to have higher baseline BP readings, while those who exercise and have a normal BMI had lower BP readings.

Discussion

The study yielded insightful results, but more analysis is required to comprehend the findings completely. The study found that compared to other age groups, those in the 50–60 age range had the greatest incidence of HTN (Figure 1). Older people may be more likely to develop HTN due to physiological changes they go through. Arteries become less elastic with aging, rendering it more difficult for them to adapt to fluctuations in blood volume. Furthermore, aging can impact kidney function by increasing salt sensitivity because of some pumps’ lower activity, which increases vascular resistance and vasoconstriction.[23]

According to the findings, females have greater blood pressure than males, with rates of 58.2% and 41.8%, respectively (Figure 2). In females, this is due to increased salt sensitivity following menopause. Because of lower estrogen levels during menopause, the RAAS and sympathetic nervous systems become more active, while the availability of vascular nitric oxide decreases. As a result, during menopause, there is an increased synthesis of enormous vasoconstrictors such as angiotensin II, endothelin-1, and catecholamines.[24]

The results indicate that ACE inhibitors are commonly used by hypertensive patients compared to other antihypertensive drugs. This preference is due to several reasons. These drugs have shown effectiveness in lowering blood pressure and generally have a favorable side effects profile.[25,26] In addition to that, these medications can help prevent nephropathy by slowing down the progression of diabetic nephropathy and other renal diseases.[27] They can also improve cardiac performance, especially in patients with heart failure, by reducing afterload and enhancing blood flow.[28] Results also showed that patients who are obese tend to have higher blood pressure than those with normal or slightly increased body weight. This is because fat cells are encouraged to produce a substance that releases aldosterone. This leads to a condition called hyperaldosteronism, which is partly controlled by salt intake, abnormally high renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) levels, and activation of the sympathetic nervous system. These factors improve the reabsorption of sodium in the kidneys and can cause salt-sensitive HTN.[29]

In the study, it was found that heart diseases were the most common complications among hypertensive patients. This can be explained by the fact that HTN is a primary risk factor for Cardiovascular diseases.[30] HTN accelerates the accumulation of plaques inside the coronary arteries, which can reduce or block the blood flow to the heart.[31] When a coronary artery becomes clogged, it can lead to a heart attack.[32] Additionally, over time, HTN can cause the left ventricle of the heart to work harder, leading to thickening and weakening and potentially resulting in heart failure.[26,28]

In terms of comorbidities, the most common combination was diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia, which affected 10.5% of the participants. Several pathogenic pathways have been proposed to explain the association between HTN and diabetes mellitus. These are thought to be mediated by the adrenergic system in HTN and diabetes mellitus. One of these methods is to regulate the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system using incretins. Furthermore, a thorough investigation has been conducted on the calcium-calmodulin pathway in both circumstances. Changes in the calcium-calmodulin pathway can lead to elevated intracellular calcium levels, which impede insulin gene transcription in pancreatic β cells. These modifications cause increased arteriole stiffness, extracellular fluid expansion, and diabetic nephropathy.[33] Additionally, high cholesterol levels can impact blood pressure by enhancing the effects of vasoconstrictors like endothelin-1 and angiotensin II on the endothelium. As a result, individuals with dyslipidemia may experience a decrease in nitric oxide synthesis and an increased vasoconstrictor response, leading to elevated blood pressure.[34]

There is a relationship between exercise type, intensity, and duration with baseline blood pressure (mean=135/87), which reveals significant associations. Regular exercise has been recognized as essential for the treatment and prevention of HTN.[35] Exercise-induced blood pressure lowering is hypothesized to be caused by neurohumoral, vascular, and structural changes. Several theories have been presented to explain the antihypertensive effects of exercise, including changes in vasodilators and vasoconstrictors, lower catecholamines and total peripheral resistance, and improved insulin sensitivity.[36] Exercise that includes both resistance and aerobic components has been noticed to effectively lower blood pressure. Brisk walking is an inexpensive, simple, easy, and effective kind of physical activity that can be recommended to society.[37]

Also, it has been noted that the patients who follow the DASH diet have lower blood pressure than those who don’t follow this diet. This can be clarified by the fact that the DASH diet is an effective method to control blood pressure, which restricts sodium intake, which is the primary factor in HTN.[31] Also, it supports potassium intake, which can assist in the counterbalancing of the effects of sodium on blood pressure.[25] It contains a high amount of important nutrients such as magnesium, calcium, and fiber, which have been linked to lower blood pressure.[32] Additionally, the DASH diet limits saturated and trans fats, which are associated with elevated blood pressure, and can also help with weight management, a significant factor in controlling blood pressure.[26,28]

When it comes to salt in food, research has shown that people who consume a lot of salt often have high blood pressure. This is because excessive salt intake can lead to increased plasma volume, which is the physiological reason for elevated blood pressure. Studies indicate that retaining salt raises serum sodium levels, triggering thirst and causing plasma volume to increase, ultimately leading to higher cardiac index and blood pressure.[38]

The study found that patients who slept 6-9 hours had lower blood pressure than those who slept less than 6 hours. There are numerous causes for this outcome. Insufficient sleep can cause a rise in cortisol levels, leading to rising blood pressure, and can trigger the sympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for the fight-or-flight reaction, resulting in elevated heart rate and blood pressure.[31,25] Additionally, sleep deprivation has a substantial impact on insulin resistance, which may contribute to elevated blood pressure.[28]

Based on the findings, blood pressure is positively impacted by being adequately hydrated. There are various possible explanations for this. Adequate water consumption can assist in maintaining blood volume by reducing blood viscosity and the burden on the heart.[31] It can also cause vasodilation, which reduces blood volume and helps to reduce sympathetic nervous system activation.[25] In addition, it can help the kidneys excrete sodium, which can help reduce blood pressure.[32]

In recent years, digital health interventions have become a very useful, accessible, and effective way to deliver healthcare for the control of HTN and self-management when compared to standard care.[39] These days, common digital health strategies for controlling HTN include text message reminders for medication adherence, remote blood pressure monitoring, and virtual behavioral coaching.[40] Several meta-analyses revealed that, in contrast to in-person delivery, digital health treatments reduced HTN patients’ systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Nevertheless, such meta-analyses were insufficient since the total sample size was smaller and there was less research from LMICs included.[39]

Numerous studies have demonstrated that physical activity, eating habits, sleep patterns, and modern technologies all play significant roles in the treatment and prevention of HTN. A study conducted on the Ferrari corporate population in 2021 discovered that individuals with higher levels of cardiorespiratory fitness had decreased rates of high blood pressure, even after considering other factors such as age, gender, and smoking status.[41] These findings are consistent with previous research indicating that aerobic exercise is beneficial in lowering both systolic and diastolic blood pressure. A meta-analysis published in 2002 found that aerobic exercise could reduce systolic pressure by an average of 3.84 mmHg and diastolic pressure by 2.58 mmHg.[42] Additionally, exercise duration and intensity are important in treating HTN. A study published in 2015 noted that individuals who exercised for more than 60 minutes on most days of the week had better blood pressure outcomes, corroborating the Ferrari study’s findings.[43]

Diet has an important influence on blood pressure management. The DASH diet has been demonstrated to effectively control blood pressure in a variety of populations. A 1999 subgroup analysis of the DASH study found that this diet reduced blood pressure without causing weight loss or sodium reduction, with African American individuals benefiting the most.[44] Another important aspect is sleeping duration; a 2006 study found that short sleep intervals (less than six hours) were related to an increased risk of HTN, but intermediate sleep (7-8 hours) was associated with improved blood pressure regulation.[45]

Recent technological advancements have introduced wearable devices and smartphone applications designed to monitor blood pressure. A meta-analysis in 2022 found that app-based self-monitoring led to a slight reduction in blood pressure and improved adherence to treatment, further supporting the utility of technology in HTN management.[46]

Limitations and expectations

The study glanced at the association between lifestyle and other factors that affect blood pressure in individuals with HTN. However, it is crucial to recognize the limitations of the research.

Firstly, while the Jordanian Ministry of Health reports that 22.1% of the Jordanian population suffers from HTN, the study’s representative sample of 1002 may not adequately reflect the entire number of hypertensive individuals. However, it is appropriate for statistical analysis.

Second, the data were gathered using self-reported lifestyle variables, such as exercise frequency, food, sleep patterns, and technology use. This method may introduce biases, including recall bias and social desirability bias, which might compromise the accuracy of the findings. To address these limitations, future research should look at larger and more diverse samples, longitudinal designs, and more rigorous data collection methods. Furthermore, it is crucial to emphasize that our study’s findings might not be relevant to other countries due to cultural and demographic differences peculiar to the geographical region where the study was done. Additionally, finding patients willing to participate in the interview presented various obstacles. These challenges included concerns about the privacy of sensitive information and personal health data being studied. Patients may also have difficulties arranging an appropriate interview time owing to busy schedules, medical appointments, treatments, or employment responsibilities.

Finally, to address the challenges and increase patient recruitment, researchers focused on building trust, addressing privacy concerns, providing clear information, and offering support and benefits as an incentive for participation. Furthermore, implementing changes in lifestyle and promoting knowledge about the benefits of exercise and healthy habits can help lower blood pressure and enhance quality of life. Furthermore, integrating more technology and artificial intelligence into blood pressure treatment can make monitoring and regulating blood pressure easier and faster.

Conclusion

The research revealed a substantial link between BP and other factors, including frequent exercise and sports. The analysis found a significant correlation between aerobic activities such as running and walking and lower blood pressure levels (Cramer’s V value of 0.961). Strength training also revealed a high correlation with decreased blood pressure (Cramer’s V value of 0.811). Individuals who exercised for more than 60 minutes daily, five days a week, had reduced blood pressure (Cramer’s V value of 0.838). The DASH diet, which is low in sodium and high in fruits and vegetables, helps decrease blood pressure (p<0.001). Sleep time was also associated with reduced blood pressure (p<0.0001). Furthermore, smartwatches that monitor blood pressure could lower BP, with a Chi-Square value of 1814.341 (p<0.0001) and a Cramer’s V of 0.952.

References

- World Health Organization. Hypertension. Accessed August 2021. Hypertension

- American Heart Association. High Blood Pressure. Accessed December 2020. High Blood Pressure

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. High Blood Pressure. Accessed August 2021. High Blood Pressure

- Elliott WJ. Systemic hypertension. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2007;32(4):201-259. doi:10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2007.01.002 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Desai AN. High blood pressure. JAMA. 2020;324(12):1254. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.11289 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Atibila F, Ten Hoor G, Donkoh ET, Kok G. Challenges experienced by patients with hypertension in Ghana: A qualitative inquiry. PLoS One. 2021;16(5):e0250355. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0250355 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Flack JM, Adekola B. Blood pressure and the new ACC/AHA hypertension guidelines. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2020;30(3):160-164. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2019.05.003 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rossi GP, Bagordo D, Rossi FB, et al. “Essential” arterial hypertension: Time for a paradigm change. J Hypertens. 2024;42(8):1298-1304. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000003767 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Tasnim S, Tang C, Musini VM, Wright JM. Effect of alcohol on blood pressure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;7(7):CD012787. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012787.pub2 PubMedv | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rossi GP, Bisogni V, Rossitto G, et al. Practice recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of the most common forms of secondary hypertension. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2020;27(6):547-560. doi:10.1007/s40292-020-00415-9 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Tziomalos K. Secondary hypertension: Novel insights. Curr Hypertens Rev. 2020;16(1):11-18. doi:10.2174/1573402115666190416161116 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Alhawari H, AlShelleh S, Alhawari H, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed hypertension and its predictors in Jordan: A cross-sectional study. Int J Gen Med. 2022;15:7919-7928. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S388121 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mills KT, Stefanescu A, He J. The global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(4):223-237. doi:10.1038/s41581-019-0244-2 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2224-2260. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Jaddou HY, Bateiha AM, Al-Khateeb MS, Ajlouni KM. Epidemiology and management of hypertension among Bedouins in Northern Jordan. Saudi Med J. 2003;24(5):472-476. Epidemiology and management of hypertension among Bedouins in Northern Jordan

- Rehman S, Nelson VL. Blood pressure measurement. StatPearls. Published December 28, 2022. Blood Pressure Measurement

- Carlson DJ, Dieberg G, McFarlane JR, Smart NA. Blood pressure measurements in research. Blood Press Monit. 2019;24(1):18-23. doi:10.1097/MBP.0000000000000355 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Brașoveanu AM, Șerbănescu MS, Mălăescu DN, Predescu OI, Cotoi BV. High Blood Pressure-A High Risk Problem for Public Healthcare. Curr Health Sci J. 2019;45(3):251-257. doi:10.12865/CHSJ.45.03.01

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Ameer OZ. Hypertension in chronic kidney disease: What lies behind the scene. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:949260. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.949260 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Boehme AK, Esenwa C, Elkind MSV. Stroke risk factors, genetics, and prevention. Circ Res. 2017;120(3):472-495. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308398 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bhargava M, Ikram MK, Wong TY. How does hypertension affect your eyes? J Hum Hypertens. 2011;26(2):71-83. doi:10.1038/jhh.2011.37 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Santisteban MM, Iadecola C, Carnevale D. Hypertension, neurovascular dysfunction, and cognitive impairment. Hypertension. 2022;79(4):681-693. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.18085 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Oliveros E, Patel H, Kyung S, et al. Hypertension in older adults: Assessment, management, and challenges. Clin Cardiol. 2020;43(2):99-107. doi:10.1002/clc.23303 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gerdts E, Sudano I, Brouwers S, et al. Sex differences in arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(46):4777-4788. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehac470 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Silcocks PB, Robinson D. Completeness of ascertainment by cancer registries: Putting bounds on the number of missing cases. J Public Health (Oxf). 2004;26(2):161-167. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdh140

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Demers C, Mody A, Teo KK, McKelvie RS. ACE inhibitors in heart failure: What more do we need to know? Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2005;5(6):351-359. doi:10.2165/00129784-200505060-00002 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Beckwith C, Munger MA. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on ventricular remodeling and survival following myocardial infarction. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27(6):755-766. doi:10.1177/106002809302700617 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Fujii M, Wada A, Tsutamoto T, et al. Bradykinin improves left ventricular diastolic function under long-term angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in heart failure. 2002;39(5):952-957. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000015613.78314.9E PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kawarazaki W, Fujita T. Role of Rho in salt-sensitive hypertension. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(6):2958. doi:10.3390/ijms22062958 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Guasti L, Ambrosetti M, Ferrari M, et al. Management of hypertension in the elderly and frail patient. Drugs Aging. 2022;39(10):763-772. doi:10.1007/s40266-022-00966-7 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rydberg P. Comment on “binding free energies of inhibitors to iron porphyrin complex as a model for cytochrome P450”. 2012;97(4):250-251. doi:10.1002/bip.22018 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kshirsagar AV, Joy MS, Hogan SL, et al. Effect of ACE inhibitors in diabetic and nondiabetic chronic renal disease: A systematic overview of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35(4):695-707. doi:10.1016/S0272-6386(00)70018-7 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cryer MJ, Horani T, DiPette DJ. Diabetes and hypertension: A comparative review of current guidelines. J Clin Hypertens. 2016;18(2):95-100. doi:10.1111/jch.12638 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Dalal JJ, Padmanabhan TN, Jain P, et al. LIPITENSION: Interplay between dyslipidemia and hypertension. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(2):240-245. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.93742 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cornelissen VA, Fagard RH. Effects of endurance training on blood pressure, blood pressure-regulating mechanisms, and cardiovascular risk factors. 2005;46(4):667-675. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000184225.05629.51 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Pescatello LS, Franklin BA, Fagard R, Farquhar WB, Kelley GA, Ray CA; American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and hypertension. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(3):533-553. doi:10.1249/01.MSS.0000115224.88514.3A PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Alpsoy Ş. Exercise and Hypertension. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1228:153-167. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-1792-1_10 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Jiang K, He T, Ji Y, Zhu T, Jiang E. The perspective of hypertension and salt intake in Chinese population. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1125608. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1125608 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Boima V, Doku A, Agyekum F, Tuglo LS, Agyemang C. Effectiveness of digital health interventions on blood pressure control, lifestyle behaviours and adherence to medication in patients with hypertension in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. 2024;69:102432. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102432 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Katz ME, Mszar R, Grimshaw AA, et al. Digital Health Interventions for Hypertension Management in US Populations Experiencing Health Disparities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(2). doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.56070 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Biffi A, Gallo G, Fernando F, et al. Relationship Between Cardiorespiratory Fitness, Baseline Blood Pressure and Hypertensive Response to Exercise in the Ferrari Corporate Population. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2022;29:81-88. doi:10.1007/s40292-021-00491-5 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Whelton SP, Chin A, Xin X, He J. Effect of aerobic exercise on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(7):493-503. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-136-7-200204020-00006 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Pescatello LS, MacDonald HV, Lamberti L, et al. Exercise for Hypertension: A Prescription Update Integrating Existing Recommendations with Emerging Research. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2015;17:87. doi:10.1007/s11906-015-0600-y PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Svetkey LP, Simons-Morton D, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure: Subgroup analysis of the DASH randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(3):285-293. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.3.285 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gangwisch JE, Heymsfield SB, Boden-Albala B, et al. Short sleep duration as a risk factor for hypertension: Analyses of the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2006;47(5):833-839. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000217362.34748.e0 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kassavou A, Wang M, Mirzaei V, Shpendi S, Hasan R. The Association Between Smartphone App-Based Self-monitoring of Hypertension-Related Behaviors and Reductions in High Blood Pressure: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2022;10(7). doi:10.2196/34767 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgment

Not reported

Funding

Not reported

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Saed Bani Amer

Department of Medicine

Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

Email: saedbamer0000@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Ahmad Hayajneh, Lena Almemeh

Department of Medicine

Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

Balqees Jawarneh, Shahed Almefleh, Taymaa Al-Ababneh, Muna Hijazi, Lara Al-Qudah, Lina Badawneh

Department of Medicine

Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

Hashem Al-Shorman, Hasan Al-Khateeb

Department of Internal Medicine Specialist and Consultant

Princess Basma Hospital, Jordan

Qaed Bani Amer

Department of Internal Medicine

Princess Basma Hospital, Jordan

Raed Bani Amer, Mahmoud Hayajneh

Department of Medicine

Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in strict accordance with the ethical standards established by the hospital’s research committee, adhering to the principles outlined in the 1964 declaration of helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The research protocol was rigorously reviewed and granted approval by the hospital’s research committee (IRB approval number: IRB/2024/4713). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were thoroughly briefed on the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Not reported

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Saed Bani A, Ahmad H, Lena A, et al. Critical Determinants of Blood Pressure Control: The Impact of Lifestyle, Environment, and Other Parameters in Patients with Hypertension – A Jordanian-based Cross-Sectional Study. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622413. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622413 Crossref