Author Affiliations

Abstract

Occupational and baker’s asthma are well-understood forms of airway restriction and hypersensitivity. Serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) monitoring is often recommended to aid in the diagnosis of baker’s asthma, but is rarely used to monitor temporal changes in IgE levels. Combined with the use of serial spirometry, this case aims to provide evidence that serial IgE testing can be used to show that removal from the antigen source leads to decreased IgE levels, improved spirometry results, and coincidence improved clinical symptoms of patients suffering from Occupational asthma (OA).

Keywords

Baker’s Asthma, Hypersensitivity, High molecular weight allergen, Immunoglobulin E, Forced vital capacity, Forced expiratory volume.

Introduction

OA is an obstructive, inflammatory, and/or hyperresponsive pathologic response to an agent specific to a workplace.[1] Baker’s asthma (flour-induced or grain-induced asthma) is one of the oldest known and most common types of OA (roughly 15%). This type of asthma occurs secondary to allergens present in bakeries, such as wheat/rye grains and other baking additives.[2,3] The pathophysiologic IgE-mediated hypersensitivity response to the high-molecular-weight allergen causes airway infiltration with inflammatory cells, followed by edema and loss of epithelial integrity.[3] The IgE-mediated response can be monitored using IgE serum testing. IgE levels above 0.35 kU/L indicate a sensitivity to the allergen, and subsequent decreases in IgE levels over time indicate decay of IgE antibodies without re-exposure.[4] While IgE levels are indicative of sensitivity to a known allergen, the magnitude of IgE levels does not always correspond with the severity of symptoms, especially if the patient is no longer exposed to the antigen.[4] Thus, pre-existing conditions and changes should be monitored to understand how exposure is affecting the patient. Asthma that is pre-existing can be exacerbated by workplace allergen exposures, and a history of atopy is a risk factor for developing OA.[1,5]

Key findings in the history of a patient with suspected OA are prior asthma symptoms, smoking history, history of accidental hazardous exposures, improvement of symptoms outside of the workplace, and exposure to known allergy-inducing agents at work. Diagnosing OA requires establishing the relationship between the disease and the workplace by demonstrating a pattern of correlative symptomatology relative to the employee’s presence in the work environment. In addition, the employee must have some combination of wheezing, shortness of breath, cough, or chest tightness while working or within 4-8 hours of leaving the workplace.[1] Treatments for OA include the same treatments for non-OA, including supportive care, bronchodilators, corticosteroids, cessation of smoking, as well as reducing and eliminating exposures to OA-inducing agents in the workplace.[5] Total and specific serum IgE measurements have been demonstrated to have a value in medical monitoring and in evaluating the success of hazard controls for various types of OA, including both baker’s asthma and animal allergen-induced asthma.[4,6] Interestingly, a single study of specific serum IgE laboratory animal allergen context has demonstrated that reduction of IgE levels improved hazard controls, suggestive of the potential for specific IgE monitoring as a means to evaluate exposure.[9] This report focuses on the correlation between serial serum IgE and spirometry results in a case of OA.

Case Presentation

A 26-year-old male presented to his primary care provider (PCP) approximately two years after starting employment at a food manufacturing company. For one year, he worked five to seven days per week, packing materials, mixing wheat and oat flour for baked goods, and weighing flour portions for baking. He reported wheezing, dyspnea, and chest tightness worsened at work and improved after work. Prior to these symptoms, the patient had no history of lung disease or asthma, did not smoke, and did not have any known food or airborne allergies. His initial 3 months of treatment consisted of empirical treatment with as-needed inhaled and nebulized albuterol. He did not initially undergo spirometry or pulmonary function testing, but his peak flows dropped as much as 40-50% while at work, versus outside of work, and demonstrated similar improvement in the clinic following administration of albuterol. During this time, various workplace accommodations were attempted with variable degrees of symptomatic success, but his symptoms persisted. His symptoms nevertheless worsened, and daily use of albuterol was recommended in addition to a short course of oral prednisone, and he was referred to occupational medicine for causation evaluation and workability management of presumed OA.

Case Management

Upon initial evaluation, he was asymptomatic after his recent course of prednisone and scheduled use of albuterol, and he was consequently returned to the workplace with advisement to carry his albuterol with him and to wear an N95 respirator. The spirometry on his initial evaluation was relatively normal (Forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume 1 (FEV1), FEV1/FVC at 84.0%, 84.6%, 100.4% of predicted values according to NHANES III reference values), and his FEV1/FVC only increased 7.9% after administration of albuterol. He returned to the clinic 3 weeks later (4 months after symptom onset), at which time he continued to be asymptomatic due to primarily being out of work in the interim due to a slower production schedule. Despite this, he noted being unable to tolerate wearing an N95 because of difficulty breathing, and spirometry was slightly worse, so it was recommended that he try various respirators as part of his workability.

The employee did not return to the occupational medicine clinic until 4 months later (8 months after symptom onset), after he had presented to his PCP again one month prior with an asthma exacerbation, resulting in general work restrictions being provided for the employee to work as far away from flour dust as possible. On this visit, he was doing well with respect to his symptoms, though he was having difficulty playing soccer due to shortness of breath; occupational medicine clarified his restrictions on this visit to limit work duties. His spirometry was again worsened from prior evaluation, and serum IgE testing demonstrated a very high total IgE in addition to elevated allergic response to several common allergens, wheat, and oat. He was additionally referred to a pulmonologist for evaluation, who agreed with his treatment plan and prescribed the use of an H1 antihistamine.

He returned to occupational medicine three days later with an acute exacerbation following his new restrictions, with his spirometry demonstrating FVC at 59% of predicted, FEV1 at 48% predicted, and FEV1/FVC at 81% predicted; his restrictions were again generalized to have him avoid exposure to flour as well as wheat and oat products. His workplace was unable to accommodate his modified restrictions, and he was removed from the workplace. When he returned to work 2.5 weeks later, he was asymptomatic, his spirometry had significantly improved, and he was tolerating playing soccer without the use of albuterol. Repeat serum IgE testing at this time was further elevated from his initial tests.

He followed up with occupational medicine 10 months after his symptom onset, having not returned to work, and he was asymptomatic on daily cetirizine without any use of albuterol, even in increased activity. Spirometry was stable from his previous evaluation. Serum IgE at this time showed decreased oat and wheat response, though common allergens for the season (grasses) were elevated more than previously. He was provided with permanent work restrictions at that visit and directed to follow up at one year after his initial presentation to occupational medicine for a permanent partial disability (PPD) rating. He returned at 18 months following his initial symptoms and was doing well in different employment without exposure to flour dust. His spirometry remained stable, and his serum IgE to oat and wheat continued to decline, while a common respiratory allergen for the season (ragweed) was increased. The patient was determined to be at maximum medical improvement (MMI) at this time, with a 10% PPD rating per Minnesota statutes based on his FEV1, FEV1/FVC, and PD20 (2.5 mg/mL) as measured by formal pulmonary function test (PFT) with positive methacholine challenge testing performed near the time of this visit.

Discussion

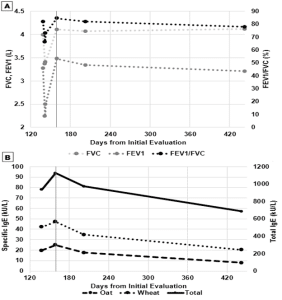

While OA and baker’s asthma are well-understood, the methodology of monitoring a patient’s IgE levels serially in conjunction with serial spirometry has not yet been thoroughly described in the literature prior to this study.[2] Notably, the data shows an inverse correlation between spirometry and specific IgE levels, which indicates that monitoring specific IgE may help in monitoring the patient’s immunologic response to exposures (or the lack thereof), and is consistent with literature showing similar correlations between total IgE and FEV1.[7] While the patient’s lowest FEV1/FVC did not align with the highest specific IgE levels, it is presumed that a lagging in IgE development after removal from the work environment is responsible, though the patient’s initially presented IgE levels in Figure 1 prior to their peak were already positive (> 0.35 kU/L).

Ultimately, the patient’s symptoms were greatly reduced after removal from exposure, and his reduced immunologic response was quantitatively demonstrated by his IgE and spirometry results. These results show a sustained, but significantly reduced IgE response without exposure, as well as an increased susceptibility and atopy upon continued exposure, which is consistent with OA.[2,3] In addition, these results are congruous with those of Thulin et al., in that specific serum IgE can correlate with exposure mitigation in occupational contexts.[8]

The use of specific IgE testing allowed for quantitative evidence of the patient’s sensitivity to wheat and oat, rather than relying solely on qualitative symptomatology or patient-reported peak flow readings to conclude a diagnosis of OA. His IgE levels for the allergens of wheat and oat, to which he was particularly exposed, were significantly above normal limits, consistent with his presence in the environment as a mediator of exposure. This was further shown by the reduction of IgE levels over time after removal from areas with flour dust. While IgE testing was used within this patient’s clinical care to aid in the diagnosis of OA, it must be noted that it should not be the sole diagnostic measure.[1, 9, 10] In this case, serial spirometry was used to quantify the improvement of the patient’s asthma as a supplement to monitoring his overall symptomatology over time.

Figure 1: A) Serial spirometry (FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC) measurements throughout OA evaluation. A line is marked at day 159 to show when the patient was first evaluated after leaving work on day 145.

B) Serial serum IgE (total, wheat, oat) measurements throughout OA evaluation. A line is marked at day 159 to demonstrate when the patient was first evaluated after leaving work on day 145.

Conclusion

Serum IgE testing was used in place of the commonly used skin prick test to quantify IgE levels and reduce patient discomfort. While the skin prick test is useful in determining if a patient has a sensitivity to an allergen by virtue of observing histamine response, it does not necessarily demonstrate exposure to an allergen. This case suggests that serial monitoring of specific serum IgE levels may be useful in causation analysis and surveillance of OA, though further study is required to develop statistical inference or guidelines regarding these kinds of results.

References

- Jolly AT, Klees JE, Pacheco KA, et al. Work-related asthma. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57(10):e121-e129. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000000572. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bittner C, Garrido MV, Harth V, Preisser AM. IgE reactivity, work-related allergic symptoms, asthma severity, and quality of life in bakers with occupational asthma. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;921:51-60. doi:10.1007/5584_2016_226 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Tarlo SM, Lemiere C. Occupational asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(7):640-649. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1301758 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hamilton RG, Oppenheimer J. Serological IgE analyses in the diagnostic algorithm for allergic disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(6):833-840; quiz 841-842. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2015.08.016 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ameille J. Hunter’s Diseases of Occupations. 10th Edition. Eur Respir Rev. 2011;20(122):302. Hunter’s Diseases of Occupations. 10th Edition

- Baur X, Sigsgaard T, Aasen TOB, Burge PS. ERS task force on the management of work-related asthma. Guidelines for the management of work-related asthma. Eur Respir J. 2012;39(3):529-545. doi:10.1183/09031936.00096111 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Al Obaidi AHA, Al Samarai AGM, Al Samarai AKY, Al Janabi JM. The predictive value of IgE as a biomarker in asthma. J Asthma. 2008;45(8):654-663. doi:10.1080/02770900802126958 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Thulin H, Björkdahl M, Karlsson A-S, Renström A. Reduction of exposure to laboratory animal allergens in a research laboratory. Ann Occup Hyg. 2002;46(1):61-68. doi:10.1093/annhyg/mef022 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Corradi M, Ferdenzi E, Mutti A. The characteristics, treatment and prevention of laboratory animal allergy. Lab Anim (NY). 2012;42(1):26-33. doi:10.1038/laban.163 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sander I, Rihs H-P, Doekes G, et al. Component-resolved diagnosis of baker’s allergy based on specific IgE to recombinant wheat flour proteins. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(6):1529-1537. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.11.021 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

The authors report that there was no funding source for the work that resulted in the article or the preparation of the article.

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Dominik S Dabrowski

Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine

School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, USA

Email: dabrowskidom@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Zeke J. McKinney

Department of Environmental Health Sciences

University of Minnesota, USA

Jonathon R. Swan

Department of Psychology

University of Minnesota, USA

Emma E. Alley

Department of Emergency Medicine

Geisinger Medical Center, USA

Blair M. Anderson

Department of Pulmonary Medicine

HealthPartners, USA

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Ethical Approval

Clinical work for this case report was performed within HealthPartners occupational and environmental medicine as well as in HealthPartners pulmonary and sleep medicine. Institutional review board (IRB) oversight for these institutions is conducted within the HealthPartners Institute. No IRB approval/review nor informed consent was obtained or required institutionally for this case, given that this work was conducted clinically as part of the standard of care for a single patient and is reported in retrospect.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Dominik SD, Zeke JM, Jonathon RS, Emma EA, Blair MA. Correlation of serial IgE and spirometry in a case of Baker’s asthma. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622431. doi:10. 63096/medtigo30622431 Crossref