Author Affiliations

Abstract

Background: Surgical site infection (SSI) is among the most common problems for patients who undergo surgical procedures. It remains a prevalent problem that contributes to morbidity and mortality due to the incidence of antimicrobial-resistant bacterial pathogens.

Objective: To determine the pattern of drug susceptibility and bacterial pathogens isolated from SSI at Myungsung Christian Medical (MCM) comprehensive specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Methodology: A retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted at MCM comprehensive specialized hospital on surgical patients with postoperative surgical site infections that have culture and sensitivity tests between January 2019 and January 2022. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics data were collected through a retrospective assessment of medical records from the microbiology laboratory unit. Finally, data were analyzed using the statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 25 for Windows software.

Results: A total of 74 cases with culture growth and sensitivity tests were found from SSI during the study period. Of these isolates, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii were the most common growths, 14/74 (18.9%) and 13/74 (17.5%) respectively, with 58 (78.4%) being gram-negative isolates. Of all the isolates obtained, 58/74 (78.4%) were multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains. More than eighty percent of gram-negative isolates were MDR strains.

Conclusion: Most of the isolates found in SSI were gram-negative bacteria, and nearly half of all the isolates obtained were accounted for by gram-negative multidrug-resistant strains. From the results of our study, we recommend a prior antibiotic susceptibility test before treating any SSI due to the high prevalence of MDR among isolates.

Keywords

Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, Bacterial pathogens, Surgical site infection, Hospital-acquired, Prophylaxis.

Introduction

An SSI is defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as an infection that occurs after surgery in the part of the body where the surgery took place. SSIs can be superficial infections involving the skin only, whereas in more severe cases, they can also involve tissues under the skin, organs, or implanted material.[1]

SSI is a dangerous condition with a heavy burden on the patient and has been associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs, with a significant economic impact. Hospital-acquired SSIs are one of the major health problems throughout the world and are serious complications affecting hospitalized patients. Hospital-acquired SSIs are among the most common problems for patients who undergo operative procedures and the third most commonly stated hospital-acquired infection in inpatient departments.[1-3]

In most developing countries like Ethiopia, it is common knowledge that antibiotics can be obtained without a prescription.[2] This leads to the misuse of antibiotics by the community, thus contributing to the emergence and increased extent of antimicrobial resistance. However, studies evaluating the etiological agents of SSI in Ethiopia are very limited.[3]

The extent of these antimicrobial-resistant bacterial strains worldwide is unknown due to limited data in different countries. The issue is worse in developing countries, where even fewer studies are available. In Ethiopia, there has been limited data regarding the magnitude of SSIs due to antimicrobial-resistant pathogens as well as susceptibility patterns to commonly prescribed antibiotics used in the treatment of these infections.[4]

This study will be carried out to establish local data, mainly on the magnitude of SSI due to antimicrobial-resistant pathogenic bacteria, as well as their susceptibility pattern in various surgical specialties at the MCM.[5] Taking such data helps to create guidelines for the management of SSIs and contributes to the development of surveillance, prevention, and control of surgical site infections.[6]

Methodology

Study design and setting: A facility (hospital) based retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted at MCM comprehensive specialized hospital from January 2019 to January 2022. MCM hospital is a tertiary comprehensive teaching hospital that is located in the Gerji region in bole sub-city in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Study population: All patients with documented surgical site infections with culture done at MCM during the study period.

Study subject: All patients with documented surgical site infections with positive culture results and sensitivity tests had been done during the study period.

Inclusion criteria

- Presence of postoperative SSIs (both inpatients and outpatients, and both elective and emergency surgeries)

- Presence of culture and antimicrobial susceptibility test results

- Complete data and recordings

Exclusion criteria: Patients who underwent surgery at another facility but were ultimately evaluated and/or admitted at MCM.

Selection process: The sampling was done by selecting all positive culture results from those sent for patients with surgical site infections from a registry in the microbiology laboratory unit of MCM. The antibiotic sensitivity pattern was then identified from the microbiology database.

Data collection procedures

Laboratory data collection: The information on identified pathogens and antibiotic susceptibility results of different pathogenic organisms to various antimicrobial drugs was collected from a microbiology database. Microbiologic culture and sensitivity were done using the VITEK2 automated system, which was operated and calibrated using updated clinical and laboratory standards institute (CLSI) guidelines (version 2019- 2021).

Antibiotics used: A total of 35 antibiotics were included in this study. These were amikacin, ampicillin, ampicillin-sulbactam, augmentin, aztreonam, cefalotin, cefazolin, cefepime, cefotaxime, cefoxitin, cefopodoxime, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, cefuroxime, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin (CIP), clindamycin (CLI), ertapenem, erythromycin (ERY), gentamycin (GEN), imipenem, levofloxacin, linezolid (LZD), meropenem, moxifloxacin, nitrofurantoin, penicillin (PEN), pipracillin-tazobactam, oxacillin (OXA), tetracycline (TET), tigecycline (TGC), tobramycin, cotrimoxazole (SXT), rifampicin and vancomycin (VAN).

Patient data collection: The demographic data, such as age and sex data, length of hospital stays, case type (Emergency VS Elective), procedure name, and the presence or absence of preoperative antimicrobial prophylaxis, were extracted from the patients’ medical records using a questionnaire.

Operational definition

Antimicrobial susceptibility: Organisms whose isolates are inhibited by the usually achievable concentrations of the antimicrobial agent when the recommended dosage is used and reported as sensitive by the microbiology laboratory

unit.[7]

Antimicrobial resistance: Organisms whose isolates are not inhibited by the usually achievable concentrations of the agent with normal dosage and reported as resistance by the microbiology laboratory unit.[8]

Prophylaxis taken: If an antimicrobial is given within 60 minutes before the surgical incision.[9]

MDR strain: Acquired non-susceptibility to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories.[10]

Data analysis: Data was cleaned, edited, and subsequently entered into the SPSS version 25 for Windows software for further processing and analysis. Descriptive statistics were calculated using the median and interquartile range.

Ethical consideration: Ethical clearance from the MCM research ethics committees (REC) or the institutional review board (IRB) was obtained before the research began. Permission was obtained from MCM. The participants’ names were kept confidential to provide anonymity.

Results

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics: A total of 74 cases with culture growth and sensitivity tests were found from SSI during the study period. The median age of the study population was 45.5 (32.5) years (1 month- 88 years). The majority, 47 (63.5%), of the study cases were males. Out of the total study cases, 30 (40.5%) were from general surgery, while 28 (37.8%) were from neurosurgery. About 50 (67.6%) patients underwent elective surgery and the most common surgical procedures were laparotomy 11 (14.9%) and tracheostomy 11 (14.9%) followed by ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt insertion 7 (9.5%) and external ventricular drains (EVD) insertion 6 (8.1%). 53 out of 74 patients studied (70.3%) received prophylaxis before surgery was undertaken. For most patients, the time at which surgical prophylaxis was given ranged from 30 to 60 minutes before surgery. The median hospital stay of patients was 19 days (2 – 143 days) (Table 1).

| Variables | N (%) | |

| Age group (Year(s) Old) | < 1 | 8(10.8) |

| 2-15 | 3(4.1) | |

| 16-30 | 14(18.9) | |

| 31-44 | 11(14.9) | |

| 45-59 | 18(24.3) | |

| > 60 | 20(27) | |

| Total | 74(100) | |

| Sex | Female | 27(36.5) |

| Male | 47(63.5 | |

| Total | 74(100) | |

| Case type | Elective | 50(67.6) |

| Emergency | 24(32.4) | |

| Total | 74(100) | |

| Surgical patient type

|

General surgery | 30(40.5) |

| Neurosurgery | 28(37.8) | |

| Orthopedics | 9(12.2) | |

| Plastic surgery | 4(5.4) | |

| Urology | 1(1.4) | |

| ENT | 1(1.4) | |

| Maxillofacial | 1(1.4) | |

| Total | 74(100) | |

| Prophylaxis | Yes | 52(70.3) |

| No | 22(29.7) | |

| Total | 74(100) | |

| Hospital stay group (Days) | < 10 | 21(28.4) |

| 10-20 | 17(23.0) | |

| 21-30 | 14(18.4) | |

| 31-60 | 11(14.9) | |

| > 60 | 11(14.9) | |

| Total | 74(100) | |

Table 1: Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients with SSI at MCM

Bacterial isolates: Out of the total of 74 bacterial isolates found, 58 (78.4%) were gram-negative, while 16 (21.6%) were gram-positive. The two most common organisms identified from SSI were Klebsiella pneumoniae (K.Pneumoniae) and Acinetobacter baumannii at 14/74 (18.9%) and 13/74 (17.5%), respectively. Escherichia coli (E. coli) was the third most common growth 11/74 (14.8%) followed by Coagulase-negative staphylococcus aureus (CoNS) 8/74(10.8%). Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P.aeruginosa) accounted for 4/74 (5.4%) of the growths, whereas Salmonella enteritica, Enterobacter cloacae, and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) were found in 3/74 (4.1%) of the cultures each. Less common strains such as Pantoea dispersa and Enterococcus fecalis were also identified.

Coagulase-negative staphylococcus aureus was the most common isolate identified among infants, being isolated from 4/8 (50%) of all the cultures grown for surgical patients within the age group. Acinetobacter baumannii was grown in 5/14 (35.7%) of the cultures taken from patients aged 16-30, while Klebsiella pnuemoniae was found in 5/20 (25%) of cultures from patients 60 years or older.

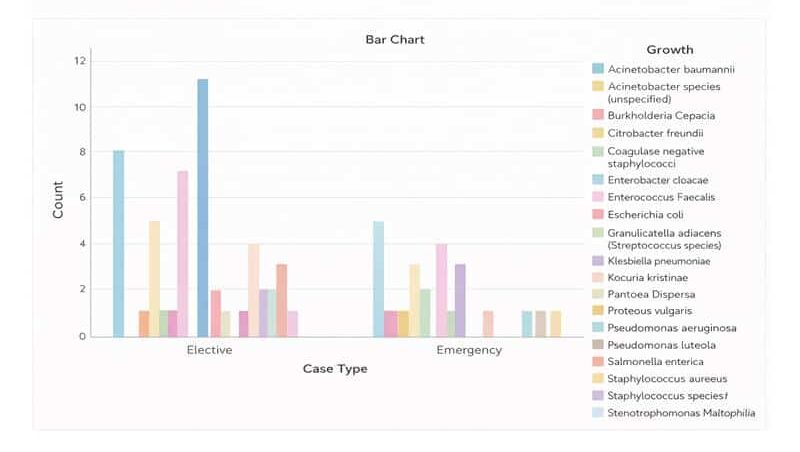

Among the elective surgeries, Klebsiella pneumonia was the most identified organism at 22.8%; while Acinetobacter baumannii was the most common organism identified from the emergency surgeries (figure 1).

Figure 1: Bacterial isolates from SSI based on case type from patients with SSI with culture growth and sensitivity test in MCM

Klebsiella pneumoniae was found in 3/5 (60%) of cultures sent from patients who underwent craniotomy, while CoNS was seen in 4/7 (57%) of the cultures sent from patients with a VP shunt inserted.

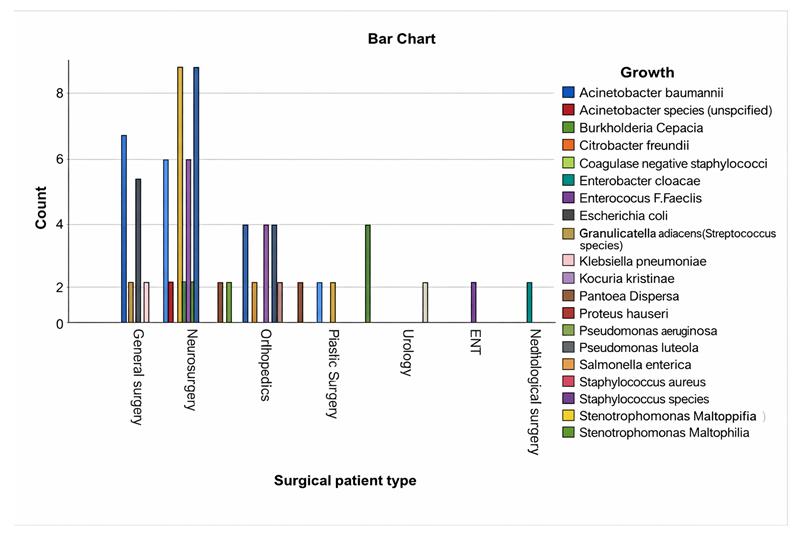

Bacterial isolates varied by surgical department, with Klebsiella pneumoniae and CoNS accounting for half of the culture growths from neurosurgical patients, while Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae were most common among general surgery patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Bacterial isolates from SSI based on surgical patient type from patients with SSI with culture growth and sensitivity test in MCM

Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern among gram-positive growth

Coagulase-negative staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus aureus are the most common isolates among the gram positives, accounting for 8/16 (50%) and 3/16 (18.8%), respectively. The drug resistance pattern of the CoNS isolates showed that 100% (4/4), 66.7% (4/6), and 57.1% (4/7) were resistant to LZD, PEN, and GEN, respectively. CoNS also showed a 2/2(100%) resistance towards oxacillin. However, more than fifty percent of CoNS were sensitive to CLI and VAN.

Two-thirds of S. aureus strains were resistant to PEN, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and CLI. Compared to findings in CoNS isolates, analysis showed that S. aureus strains were 3/3 (100%) sensitive to GEN.

Seventy-five percent of gram-positive bacteria were sensitive to VAN, but nearly 70% were resistant to PEN (Table 2).

| CONS | S. aureus | K. kristinae | E. fecalis | Strep. species | Steph. (unspecified) | |

| R | R | R | R | R | R | |

| Antibiotics | N % | N % | N % | N % | N % | N % |

| CIP | 2/3(66.7) | 0(0) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| CLI | 3/7(42.9 | 2/3(66.7) | 2/2(100) | ND | 1/1(100) | 1/1(100) |

| ERY | 5/7(71.4) | 1/2(50) | 1/1(100) | ND | ND | ND |

| GEN | 4/7(57.1) | 0(0) | 1/1(100) | ND | 0(0) | 1/1(100) |

| LZD | 4/4(100) | 0(0) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| OXA | 2/2(100) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| PEN | 4/6(66.7) | 2/3(66.7) | 2/2(100) | 0(0) | 1/1(100) | 1/1(100) |

| TET | 2/3(66.7) | 0(0) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| TGC | 2/4(50) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| SXT | 3/6(50) | 2/3(66.7) | 2/2(100) | ND | 1/1(100) | ND |

| VAN | 1/6(16.7) | 1/2(50) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

R: resistance, ND: not done

Table 2: Antimicrobial resistance profile of gram-positive bacteria isolated from SSI in MCM.

Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern among gram-negative growth

Among the gram negatives Acinetobacter baumannii, E. coli, and K. pneumoniae were the most identified gram-negative isolates. The drug resistance pattern of Acinetobacter baumannii showed that 8/10 (80%) and 10/13 (76.9%) were resistant to ceftazidime and cefepime, respectively. It also showed a 4/5 (80%), 8/13 (61.5), and 9/13 (69.2%) resistance to amikacin, tobramycin, and GEN respectively. Acinetobacter baumannii also had an 11/13 (84.6%) resistance to ciprofloxacin and an 8/10 (80%) resistance to levofloxacin. The organism was additionally found to be resistant to the carbapenem class with meropenem and imipenem resistance at 5/6 (83.3%) and 2/3 (66.7%), respectively. A. baumannii also showed a 100% resistance to piperacillin-tazobactam out of the 8 isolates tested for it.

Escherichia coli isolates also had a 1/1 (100%) resistance to commonly used antibiotics ampicillin and augmentin. The organism also showed a 100% resistance to all cephalosporins. More than eighty percent were resistant to ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin. Out of the ten E. coli isolates tested for gentamycin and tobramycin, more than fifty percent showed resistance. E. coli had an 8/9 (88.9%) resistance to the widely used antibiotic sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. Like Acinetobacter baumannii, E. coli had 100% resistance to piperacillin-tazobactam. Only two E. coli isolates were tested for the broad-spectrum antibiotic imipenem, and both were 100% sensitive.

Similar to the E. coli species, K. pneumoniae had a 100% resistance toward ampicillin. There was a high resistance toward the cephalosporin classes by K. pneumoniae. With 100% resistance towards cefuroxime and cefpodoxime, and 12/13 (92.3%), 6/7 (85%) resistance to cefepime and ceftazidime, respectively. More than seventy-five percent of K. pneumoniae were resistant to GEN and tobramycin. Unlike the other gram negatives, 6/6 (100%) Klebsiella isolates were sensitive to moxifloxacin.

Pseudomonas Aeruginosa had 100% resistance to ampicillin, augmentin, and aztreonam. However, it showed 100% sensitivity towards the aminoglycosides tested.

MDR pattern of bacterial isolates

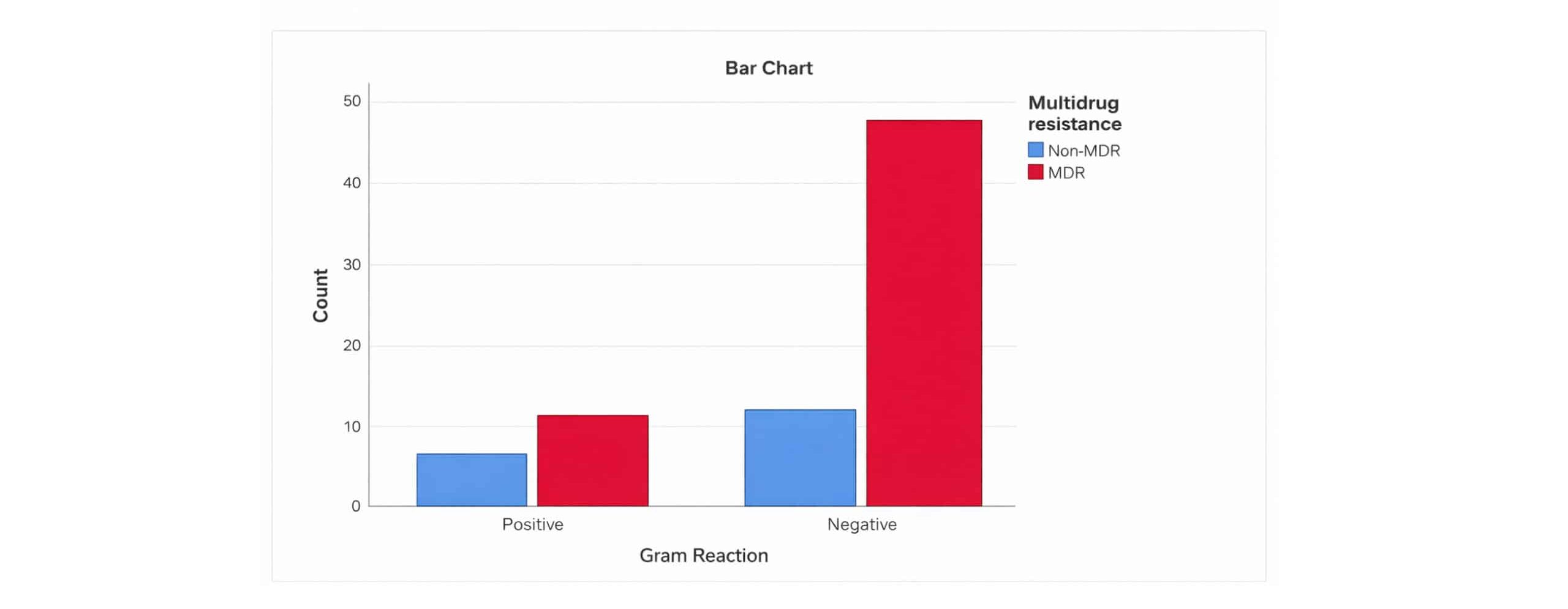

Of all the isolates obtained, 58/74 (78.4%) were MDR strains. The overall prevalence of MDR strains was 11/16 (68.8%) and 47/58 (81%) among gram-positive isolates and gram-negative isolates, respectively (Figure 3). Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase resistance was observed in 4/74 (5.4%) of all isolates. Of these isolates, two isolates were accounted for by gram-positive isolates, namely Staphylococcus aureus and CoNS. While the other two isolates consisted of Gram-negative isolates, namely E. coli. Seventy-five percent (3/4; CONS 1, E. coli 2) of isolates demonstrating extended-spectrum beta-lactamase resistance were MDR strains, while 25% (1/4; S. aureus) were non-MDR strains.

Figure 3: Distribution of MDR strains based on gram reaction among patients with SSI with culture growth and sensitivity test in MCM

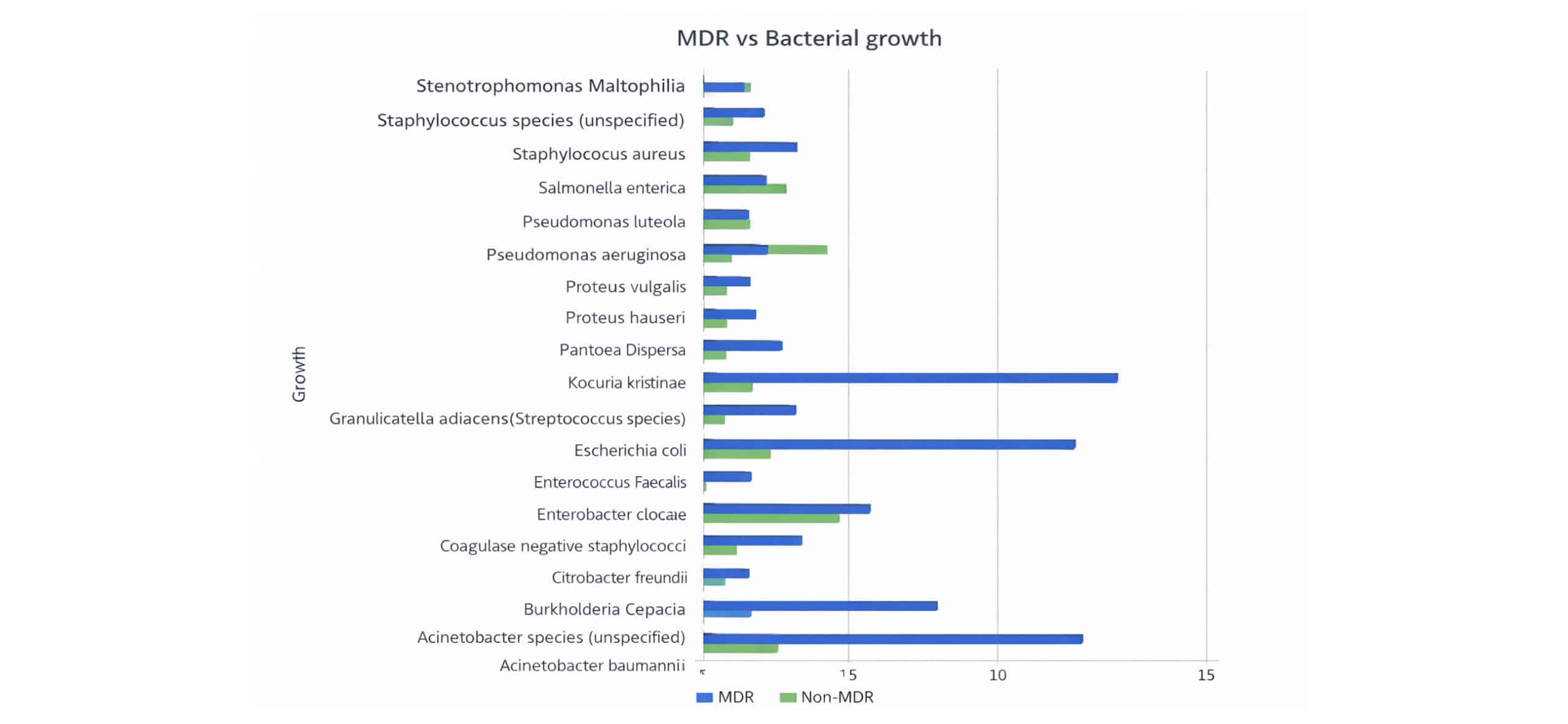

Of all the isolates, K. pneumonia, E. coli, and Acinetobacter baumannii were the isolates with the highest number and percentages of MDR strains, amounting to 13/14 (92.9%), 11/11 (100%), and 11/13 (84.6%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: MDR of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria isolated from SSI among patients with SSI with culture growth and sensitivity test in MCM

MDR strains accounted for 41/50 (82%) isolates in elective cases and 17/24 (70.8%) isolates in emergency cases. The highest number of MDR strains was seen in isolates among general surgery and neurosurgery patients, amounting to 23/30 (76.7%) and 22/28 (78.6%), respectively.

Discussion

In our study, the most identified group of organisms belonged to gram-negative bacteria, with K. pneuomoniae, Acinetobacter baumanni, and E. coli being the top three most common isolates. The overall prevalence of MDR strains among isolates obtained was high at 78.4%.

Like our findings, Enterobacteriaceae were the most common pathogens found in 73.6% of patients in a study done in Los Angeles in 2010. Of those, E.coli (54.9%) was the predominant isolate, followed by Enterobacter cloacae (26.4%), Klebsiella spp. (16.5%), and Proteus mirabilis (4.4%).[11-13] However, studies done in Belize and Karachi showed that Staphylococcus aureas was the predominant isolate from surgical site infections.[14,15] This difference in the pattern of distribution of bacterial isolates may be due to variance in the study population among facilities.

Our study showed that out of the culture growths of general surgery patients, the most common isolates were Acinetobacter baumannii followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae and E. coli. Other studies also had a similar trend, with Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa being the three most common pathogens isolated from such patients. This can be due to contamination of wounds with the patient’s endogenous flora since E. coli and other coliforms are normally found in the gastrointestinal tract.[16-19]

In our study, the predominant gram-positive isolates were CoNS and S. aureus. A study done in Gonder, Ethiopia, also showed a similar result with S. aureus and CoNS at 23.4% and 19.8%, respectively.[20] Our results showed that more than half of CoNS isolates demonstrated resistance to penicillin and 100% resistance to oxacillin, which might illustrate the presence of methicillin-resistant Coagulase-negative staphylococcus aureus (MRCoNS). CoNS showed lower resistance to vancomycin, which is in contrast to a study done in Hawassa, Ethiopia, which showed 100% resistance to vancomycin.[21] A study done in Tanzania showed that CoNS were 100% sensitive to clindamycin, but our study showed 57.1% sensitivity.[11]

According to our study, half of the S. aureus isolates were resistant to vancomycin, a drug used for the treatment of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), while studies done in the Northern part of Ethiopia showed more than 90% sensitivity toward the drug.[22] Furthermore, the results of our study show that two-thirds of S. aureus isolates were resistant to clindamycin. This is much higher than a study done in Gonder, Ethiopia, which showed a 15% resistance to clindamycin.[23]

There was a high level of resistance to commonly used antibiotics like amoxicillin, augmentin, ampicillin, and ceftriaxone among the gram negatives. Acinetobacer baumannii was one of the gram negatives which showed a high level of resistance to cephalosporins like ceftazidime, which is a study done in Addis Ababa, which showed a resistance of 82.6% towards ceftazidime.[24]

In our study, all E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and K. pneumoniae isolates were resistant to ampicillin, which was identical to other studies done in Ethiopia. Both E. coli and K. pneumoniae showed higher resistance to ciprofloxacin as compared to a study done in Jimma.[25-27] Pseudomonas aeruginosa showed a high sensitivity to gentamycin, which was similar to that of a study in Jimma. This was different from the study done in Gondar, which showed a high level of resistance to the aminoglycoside class.[28] Acinetobacter baumannii, E. coli, and K. pneumoniae displayed complete resistance to ceftriaxone, a drug used for surgical prophylaxis, and the proportion was higher than in other studies done in Ethiopia.[29]

In this hospital, a single dose of 1 gram of ceftriaxone intravenous with or without 500 milligrams of Metronidazole intravenous (depending on the need for anaerobic coverage, especially in colorectal surgery) is given up to an hour before the procedure. However, the recommended dosage is 1 gram for metronidazole while 2 grams in the case of ceftriaxone according to American society of health-system pharmacists (ASHP) guidelines. Administering a lower dose than the recommended amount not only predisposes patients to infections but also contributes to the development of resistance.[28] This shows that revaluation of antibiotics administered for prophylaxis may be needed.

Most of the gram negatives showed better sensitivity to gentamycin as compared to other drugs, thus usage of the drug in the treatment of surgical site infection could be considered. The prevalence of MDR strains among isolates obtained from SSI in our study was comparable to other studies, with the prevalence of MDR strains obtained from SSI ranging from 66% to 85%.[30] This shows that there is a high prevalence of MDR strains in isolates from SSI, which could be explained by the fact that these infections occur in a hospital setting where there is frequent exposure to antibiotics.[31]

There was a higher prevalence of MDR strains among gram negatives amounting to 81 % while MDR strains accounted for 68.8% of gram positives. The higher prevalence of MDR strains among gram negatives was reflected in most of the studies reviewed that reported gram reaction among MDR strains, with a prevalence of MDR strains among gram negatives ranging from 61% to 97%.[32]

The highest prevalence of MDR strain was seen among E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter baumannii which was similar to studies done in Tanzania and Uganda. A study done in Tanzania listed E. coli (100%), Acinetobacter baumannii (100%), and Klebsiella species (87.5%).[33] While another study done in Uganda reported that Enterobacteriaceae (73.3%) had the largest number and proportion of MDR strains.[23]

Furthermore, carbapenem resistance was completely accounted for by Acinetobacter baumannii, K. pneumoniae, and E. coli. In addition to that, all carbapenem-resistant isolates were MDR strains. This complete overlap between carbapenem resistance and multidrug resistance raises the concern of the possible presence of OXA-23-producing A. baumannii and horizontal gene transfer.[25] And considering the well-documented ability to transfer antimicrobial resistance capability genes both within and across species with nearly all methods of gene transfer, in some cases even occurring across domains, it poses the risk of further development of MDR strains. This would be very concerning as it could potentially lead to the further development of highly resistant bacteria. [22]

SSIs are generally associated with an increase in mortality, longer days of hospitalization, and adverse impact on clinical outcomes.[34] Therefore, the addition of MDR pathogens further complicates treatment by contributing to an increase in morbidity and mortality, increasing hospital stay, and increasing the cost of treatment among these patients. Furthermore, these patients are situated in intensive care units and wards with patients from other departments. This means that other patients, some of whom are immunocompromised, are also at risk of acquiring infections by MDR pathogens. In addition, as mentioned above, one of the most common isolates (Acinetobacter baumannii) carries the risk of transmitting antibiotic resistance among other pathogens. Considering these results were reported in a hospital with various departments treating thousands of patients every year, the result of the increasing prevalence of MDR pathogens would cause a general increase in morbidity, mortality, and expenditure throughout the hospital.

The study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. During our sampling, we only included patients with SSI who had positive culture results. Therefore, we are not aware of the total number of patients who may have developed a post-operative infection. This would limit the research’s ability to determine the magnitude of SSI in our hospital, thus it may impact the result we obtained. Anaerobic and fungal agents were not included in this study due to limited laboratory setup and expertise. There was no follow-up testing on MDR strains exhibiting 100% resistance to the tested antibiotics. We were unable to identify XDR strains due to a lack of complete and consistent antibiotic susceptibility testing. To that end, we could not assess the proportion of MRSA, MRCoNS, and VRSA as well.

Recommendation

From the results of our study, we recommend that a prior antibiotic susceptibility test be ordered by treating physicians before treating any SSIs due to the high patterns of MDR among isolates from SSIs. There is a need to reinforce rational Antibiotic use to limit the emergence and spread of resistance, as well as ongoing surveillance of bacterial Antibiotic sensitivity tests at the local level to guide empirical drug choice. There is also a need for further antibiotic susceptibility testing, specifically among MDR strains that show resistance to all antibiotics tested, to identify XDR strains. The practice of more targeted and consistent testing is required by the microbiology department in order to make the results more usable in terms of applying them in treatment and analysis for studies.

In addition, due to the high prevalence of resistance towards ceftriaxone among isolates from SSI and the fact that its use is not consistent with standard treatment guidelines, there may be a need to revise perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis practice guidelines in this hospital. It’s also recommended that the institution regularly fund assessments of microbial profile and antibiotic susceptibility. Developing and strengthening an infection prevention and control department should be held as a priority. Encouragement and preparation of continuing medical education programs on good antibiotic stewardship should also be a priority.

Considering the relative increase in the use of carbapenems within the past two years in this hospital, further studies should be considered in the following years to observe changes in the rates of resistance to carbapenems. Further prospective studies correlate the prevalence of MDR strains with previous antibiotic exposure, Intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and OR microbiome, as well as the association between antibiotic susceptibility patterns and preoperative prophylaxis use.

Conclusion

Most of the isolates found in SSI were gram-negative bacteria. And nearly half of all the isolates obtained were accounted for by gram-negative MDR strains, namely Acinetobacter baumannii, E.coli, and K. pneumoniae. These isolates are also the most common isolates from SSIs overall (51%).

Among the gram negatives, high rates of resistance were seen towards amoxicillin-clavulanate, cefepime, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, gentamycin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and tobramycin, while relatively lower rates of resistance were seen towards amikacin and carbapenems. And among the gram positives, more than two-thirds were resistant to penicillin, while only a quarter were resistant to vancomycin.

Furthermore, in our result, less than a tenth of the isolates were sensitive to ceftriaxone, which is the only antibiotic used in cases of surgical prophylaxis (excluding cases of beta-lactam allergies and except for Metronidazole use for anaerobic coverage). And in view of recommendations affirming the need for considering local resistance patterns and resistance patterns of organisms causing SSI before choosing antibiotics for preoperative prophylaxis, this high rate of resistance found against the only antibiotic used for preoperative prophylaxis calls its use into question.

References

- Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27(2):97-132. doi:10.1016/S0196-6553(99)70088-X PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gelaw A, Gebre-Selassie S, Tiruneh M, Fentie M. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of bacterial isolates from patients with postoperative surgical site infection, health professionals and environmental samples at a tertiary level hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Int J Pharm Ind Res. 2018;2. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of bacterial isolates from patients with postoperative surgical site infection, health professionals and environmental samples at a tertiary level hospital, Northwest Ethiopia

- Tedla BA, Abdurrahman Z, Moges B, et al. Postoperative surgical site bacterial infections and drug susceptibility patterns at Gondar University Teaching Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. J Bacteriol Parasitol. 2011;2:126-130. doi:10.4172/2155-9597.1000126 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Dessie W, Mulugeta G, Fentaw S, Mihret A, Hassen M, Abebe E. Pattern of bacterial pathogens and their susceptibility isolated from surgical site infections at selected referral hospitals, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int J Microbiol. 2016:2016:2418902. doi:10.1155/2016/2418902 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Janugade HB, Nagur BK, Sajjan KR, Biradar SB, Savsaviya JK. Abdominal surgical site infection occurrence and risk factors in Krishna Institute of Medical. Int J Sci Stud. 2016;3(11):53-56. doi:10.17354/ijss/2016/56 Google Scholar

- Kirkland KB, Briggs JP, Trivette SL, Wilkinson WE, Sexton DJ. The impact of surgical-site infections in the 1990s: attributable mortality, excess length of hospitalization, and extra costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20(11):725-730. doi:10.1086/501572 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rahman MH, Anson J. Peri-operative antibacterial prophylaxis. Pharm J. 2004;272:743-745. Peri-operative antibacterial prophylaxis

- Farina C, Goglio A, Conedera G, Minelli F, Caprioli A. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Escherichia coli O157 and other enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli isolated in Italy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15(4):351-353. doi:10.1007/BF01695674 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Nichols RL. Preventing surgical site infections: a surgeon’s perspective. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(2):220-224. doi:10.3201/eid0702.010214 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Budhani D, Kumar S, Sayal P, Singh S. Bacteriological profile and antibiogram of surgical site infection/postoperative wound infection. Int J Med Res Rev. 2016;4(11):1994-1999. doi:10.17511/ijmrr.2016.i11.17 Crossref

- Manyahi J, Kibwana U, Mgimba E, Majigo M. Multi-drug-resistant bacteria predict mortality in bloodstream infection in a tertiary setting in Tanzania. PLoS One. 2020;15(3):e0220424. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0220424 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Anderson DJ, Kaye KS, Chen LF, et al. Clinical and financial outcomes due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus surgical site infection: a multi-centre matched outcomes study. PLoS One. 2009;4(12):e8305. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008305 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Okeke IN, Lamikanra A, Edelman R. Socioeconomic and behavioral factors leading to acquired bacterial resistance to antibiotics in developing countries. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5(1):18-27. doi:10.3201/eid0501.990103 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ameh EA, Mshelbwala PM, Nasir AA, et al. Surgical site infection in children: prospective analysis of the burden and risk factors in a sub-Saharan African setting. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2009;10(2):105-9. doi:10.1089/sur.2007.082 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sasmal PK, Mishra TS, Rath S, Meher S, Mohapatra D. Port site infection in laparoscopic surgery: A review of its management. World J Clin Cases. 2015;3(10):864–871. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v3.i10.864 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Azuogu BN, Eze NC, Azuogu VC, Onah CK, Ossai EN, Agu AP. Appraisal of healthcare-seeking behavior and prevalence of workplace injury among artisans in automobile site in Abakaliki, Southeast Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2018;59(5):45-49. doi:10.4103/nmj.NMJ_110_18 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Dlamini LD, Sekikubo M, Tumukunde J, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for caesarean section at a Ugandan hospital: a randomised clinical trial evaluating the effect of administration time on the incidence of postoperative infections. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:91. doi:10.1186/s12884-015-0514-3 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Tuyud V, Thiagarajan T, Salazar D, Chun J, Perez L. Antibiotic resistance patterns of pathogens isolated from surgical site infections at public health facilities in Belize. J Antibiot Res. 2018;2(2):204. Antibiotic resistance patterns of pathogens isolated from surgical site infections at public health facilities in Belize

- Bhatiani A, Mishra V, Pal N, Chandna A. Bacteriological profile of surgical site infections and their antimicrobial susceptibility pattern at tertiary care centre in Kanpur. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2016;5:6141-6144. doi:10.14260/jemds/2016/1387 Crossref

- Prabhakar PK. Assessment of microbiological profile in surgical site infections following hollow viscus injury at a tertiary care teaching hospital. Int J Med Res Prof. 2019;5(3):304-307. doi:10.21276/ijmrp.2019.5.3.070 Crossref

- Auna AJ. Antibiotic susceptibility patterns of bacteria isolated from wards, operating room, and post-operative wound infections among patients attending Mama Lucy Hospital, Kenya. 2021. Antibiotic susceptibility patterns of bacteria isolated from wards, operating room, and post-operative wound infections among patients attending Mama Lucy Hospital, Kenya

- Ussiri EV, Mkony CA, Aziz MR. Surgical wound infection in clean-contaminated and contaminated laparotomy wounds at Muhimbili National Hospital. East Cent Afr J Surg. 2005;10(2):19-23. Surgical wound infection in clean-contaminated and contaminated laparotomy wounds at Muhimbili National Hospital

- Baguma A, Musinguzi B, Bazira J. Antimicrobial resistance profile among bacteria isolated from patients presenting with wounds at Kabale Regional Referral Hospital, Southwestern Uganda. 2020. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-17292/v1 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Fair RJ, Tor Y. Antibiotics and bacterial resistance in the 21st century. Perspect Medicin Chem. 2014;6:25-64. doi:10.4137/PMC.S14459 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Adwan G, Hasan N, Sabra I, et al. Detection of bacterial pathogens in surgical site infections and their antibiotic sensitivity profile. Int J Med Res Health Sci. 2016;5(5):75-82. Detection of bacterial pathogens in surgical site infections and their antibiotic sensitivity profile

- Mengesha RE, Kasa BG, Saravanan M, Berhe DF, Wasihun AG. Aerobic bacteria in post surgical wound infections and pattern of their antimicrobial susceptibility in Ayder Teaching and Referral Hospital, Mekelle, Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:575. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-575 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). NHSN- Surgical Site Infection Event (SSI). 2024. Surgical Site Infection Event (SSI)

- Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Olsen KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(3):195-283. doi:10.2146/ajhp120568 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Magiorakos A-P, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(3):268-81. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gebissa T, Bude B, Yasir M, et al. Bacterial isolates and their antibiotic sensitivity pattern of surgical site infections among the surgical ward patients of Asella Referral and Teaching Hospital. Futur J Pharm Sci. 2021;7:100. doi:10.1186/s43094-021-00255-x Crossref | Google Scholar

- Abosse S, Genet C, Derbie A. Antimicrobial resistance profile of bacterial isolates identified from surgical site infections at a referral hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2021;31(3):635-644. doi:10.4314/ejhs.v31i3.21 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mama M, Abdissa A, Sewunet T. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of bacterial isolates from wound infection and their sensitivity to alternative topical agents at Jimma University Specialized Hospital, South-West Ethiopia. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2014;13:14. doi:10.1186/1476-0711-13-14 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mawalla B, Mshana SE, Chalya PL, Imirzalioglu C, Mahalu W. Predictors of surgical site infections among patients undergoing major surgery at Bugando Medical Centre in Northwestern Tanzania. BMC Surg. 2011;11:21. doi:10.1186/1471-2482-11-21 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bajaj A, Rathod P, Thakur A, et al. Bacteriological profile and antimicrobial resistance of postoperative wound infections: a threat to human health. 2018;8(1):23-30. Bacteriological profile and antimicrobial resistance of postoperative wound infections: a threat to human health

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our advisors, Dr. Jeffrey Thompson, Dr. Jiksa Dabessa, and Mr. Wondimagegn Demsiss, who are always available to guide us and give us timely, constructive feedback. We would also like to acknowledge with great thanks the technicians of the Department of Microbiology at Myungsung Christian Medical Center, especially Mr. Solomon, for his advice and constructive feedback.

Funding

This study was conducted without any external funding.

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Mihiret Girma Ketema

Department of Internal Medicine

Baptist Institute of Health Science

Mbingo Baptist Hospital, Cameroon

Email: mihret.girma@mmc-edu.net

Co-Authors:

Edom Tesfaye Degefa, Leul Biruk Habtegebriel, Maranatha Tesfaye Assefa, Yeabsira Worku Atena

Department of Medicine

Myungsung Medical College, Ethiopia

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Ethical Approval

Ethical clearance from MCM REC or IRB was obtained before the research began. Permission was obtained from MCM. The participants’ names were kept confidential to provide anonymity.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Edom TD, Leul BH, Maranatha TA, Mihiret GK, Yeabsira WA. Bacterial Profile and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Patterns of Isolates Among Patients Diagnosed With Surgical Site Infection at MCM Comprehensive Specialized Hospital: Cross-sectional Study. medtigo J Med. 2024;4(4):e30622451. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622451 Crossref