Author Affiliations

Abstract

This systematic review evaluates recent advances in awake anaesthesia techniques in high-risk surgeries. The objective was to synthesize evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and clinical studies published between January 2020 and June 2025 regarding anaesthetic strategies, airway management, and perioperative outcomes. Awake surgery anaesthesia, especially in neurosurgical and thoracic contexts, has shown benefits in functional preservation, reduced intraoperative complications, and enhanced recovery. Included studies examined the effects of rocuronium-sugammadex regimens in awake craniotomy, extubation depth in nasal surgeries, regional blocks versus nebulization for airway preparation, and particle size optimization in nebulization. Findings revealed that awake approaches decrease arousal time, emergence agitation, and procedural complications while improving patient comfort and airway management. The results highlight the clinical advantages and encourage broader, evidence-based application of awake techniques, though further trials are warranted for standardization.

For patients with difficult airways, awake fiberoptic intubation is optimized using superior laryngeal nerve blocks, which show improved intubation conditions and patient comfort compared to nebulization. Among nebulization techniques, particles sized 9-10 μm offer superior patient tolerance, minimal airway reactivity, and the shortest intubation preparation. These findings highlighted the importance of individualized anaesthesia planning and support the expanded use of awake techniques in various surgical settings while underscoring the need for further high-quality trials.

Keywords

Awake surgery anaesthesia, Randomized controlled trials, Complications, Rocuronium-sugammadex, Awake craniotomy.

Introduction

Awake surgery anaesthesia has emerged as a pivotal approach in modern surgical practice, particularly in neurosurgical and spinal procedures. By enabling patient responsiveness during critical operative phases, awake techniques offer functional preservation, superior perioperative outcomes, and minimized exposure to general anaesthesia (GA). The concept primarily gained traction in AC for tumor resections near eloquent brain regions, where intraoperative neurological testing under conscious sedation facilitates maximal safe resection while preserving cognitive and motor function. More recently, its application has extended to spinal surgeries, particularly in the elderly and high-risk populations, where spinal or regional anaesthesia reduces cardiopulmonary complications and supports enhanced recovery protocols.[1-5]

Various sedative regimens, such as propofol-remifentanil, dexmedetomidine, and midazolam, have been investigated for their ability to balance patient comfort, airway safety, and neurological accessibility. Trials comparing spinal versus GA in lumbar procedures have demonstrated significant benefits of awake spinal anaesthesia in terms of reduced blood loss, operative time, hospital stay, and postoperative complications. Newer pharmacological strategies, such as the use of alpha-2 agonists and novel benzodiazepine analogs, are being evaluated to improve sedation depth control and rapid recovery.[6-10]

Awake intubation is indicated in patients with an anticipated difficult airway when securing or maintaining the airway after GA induction poses risks of failure or harm. This approach is particularly critical in cases involving severe airway obstruction, high aspiration risk, or rapid oxygen desaturation. A rare but dangerous complication of delayed or failed intubation is a post-induction “cannot intubate, cannot oxygenate” (CICO) situation, often requiring emergency front-of-neck access.[11-14]

Emergency agitation is a common complication following GA and is particularly frequent after nasal surgeries. It can lead to adverse outcomes such as self-injury and respiratory or circulatory issues. This study evaluates the incidence of emergence agitation in nasal surgery patients who were extubated either under deep anaesthesia or when fully awake. Additionally, for patients with intra-oral malignancies who often present with difficult airways, awake fiberoptic-assisted nasotracheal intubation is preferred. To enhance the success of this technique, various airway anaesthesia methods such as nerve blocks, local anaesthetic gargles, sprays, nebulization, and mild sedation are employed.[15-20]

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally, with NSCLC comprising 80-85% of all cases. However, only 25-30% of patients diagnosed with NSCLC are eligible for surgical resection. Minimally invasive approaches, such as video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) and robotic-assisted thoracic surgery (RATS), have become the preferred surgical techniques due to their association with reduced postoperative pain and shorter hospital stays.[21-23]

Traditionally, intubated GA with one-lung mechanical ventilation (MV) is considered the gold standard for airway control during these surgeries. Despite its widespread use, this approach carries notable risks. Studies have reported a 4% incidence of ventilation-induced lung injury following major lung resections performed under one-lung MV, along with a postoperative mortality rate of up to 25%.[24,25]

Thus, this systematic review aims to examine and summarize current evidence on awake anaesthesia techniques in high-risk surgeries, focusing on their effectiveness, safety, and clinical applications in airway management and surgical outcomes.

Methodology

This review article was conducted following a structured literature search to evaluate the current evidence on awake surgery anaesthesia, focusing on studies published between January 2020 and June 2025. The primary objective was to identify RCTs and prospective clinical studies that investigated anaesthesia techniques and outcomes in awake surgical procedures, particularly AC, ENT surgeries, and airway management.

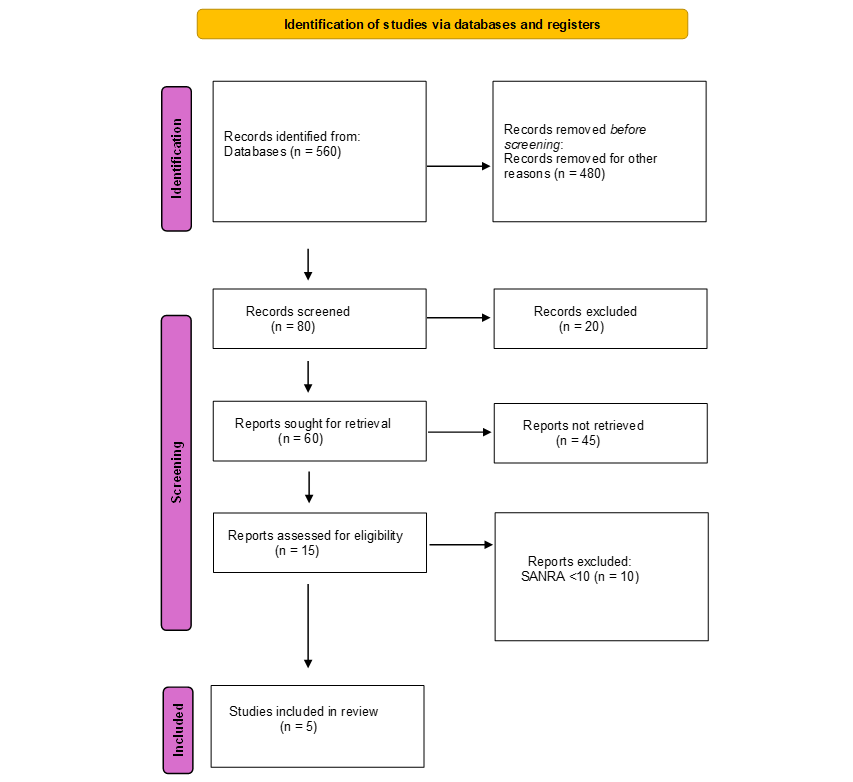

The process began with the identification of 560 records from database searches. Four hundred eighty records were removed before screening due to other reasons, likely duplicates or non-relevant material, leaving 80 records for screening. During the screening phase, 20 records were excluded based on title and abstract review, and 60 reports were sought for retrieval. While 45 of these reports could not be retrieved, possibly due to inaccessibility or unavailability of full texts.

This left 15 reports for full-text assessment of eligibility. Of these, 10 reports were excluded for scoring below the SANRA threshold (SANRA <10), which assesses the quality of narrative reviews. Finally, five studies met all the eligibility criteria and were included in the final review. A PRISMA-style flow diagram summarizing the study selection process is included in Figure 1.

A comprehensive search was performed using the PubMed database with the keywords: “awake surgery anaesthesia,” “awake craniotomy,” “awake fiberoptic intubation,” “sedation in awake neurosurgery,” and “regional anaesthesia for surgery.”

Inclusion criteria:

- Involved adult patients undergoing awake surgery with specific anaesthesia protocols

- Reported clinical outcomes such as arousal time, emergence agitation, hemodynamic stability, patient comfort, or procedural success

Exclusion criteria:

- Books, commentaries, editorials, letters, documents, and book chapters

- Articles published in languages other than English

- Animal studies and in vitro (laboratory) studies

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram

Results

Arousal dynamics and adverse events in two anaesthetic approaches for awake surgery

In Chen Y et al., a study shows that a prospective, single-blind, randomized clinical trial (NCT05202899) was conducted at the General Hospital of the Southern Theatre Command from June to November 2023, with ethics approval (NZLLKZ2023032). Forty-eight patients undergoing AC for supratentorial lesions were screened; 42 eligible patients were randomized (1:1) into either the rocuronium-sugammadex (RS) or non-RS (nRS) groups using sealed envelopes. Key exclusion criteria included pregnancy, drug allergies, major organ dysfunction, communication issues, and body mass index (BMI) ≥35 (women) or ≥42 (men).

Patients received propofol and remifentanil infusions for initial sedation. In the nRS group, a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) was inserted when the Narcotrend Index (NI) fell below 64. In the RS group, rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg) was administered, followed by LMA insertion at train of four (TOF) <25%; sugammadex (2 mg/kg) was given at TOF >25%. All drugs were stopped once brain exposure began, and the LMA was removed when NI >90. Diaphragmatic excursion, TOF, and clinical responses were monitored throughout. Mapping was performed after lesion removal. GA was used if complications increased.

Primary outcomes were awake time (drug cessation to LMA removal) and arousal quality, and standard rating scales for nausea, seizures, and shivering. Demographics, intraoperative parameters, complications, and extent of resection (total, subtotal, partial) were also recorded. Diaphragmatic ultrasound and TOF monitoring ensured respiratory and neuromuscular assessment. Data analysis employed t-tests, Mann-Whitney U, and Chi-square/Fisher’s exact tests with significance set at P<0.05. The sample size was calculated to detect a difference in awake time with 90% power.

Between June and November 2023, 48 patients were screened; six were excluded, and 42 were randomized into RS (n=21) and nRS (n=21) groups. One patient from each group did not undergo AC, and one in the nRS group was lost to follow-up, resulting in 18 patients per group for analysis. Baseline demographics, tumor types, and surgical characteristics were similar across groups (P>.05).

The RS group demonstrated significantly shorter arousal time (13.5 minutes) compared to the nRS group (21 minutes) (P< .01). However, arousal quality including VAS, OAA/S scores, and events like nausea, seizures, or shivering showed no significant differences (P=.229 and all P>.05). Propofol and remifentanil doses were comparable between groups (P>.05).

Laryngeal mask airway (LMA) adjustment was less frequent in the RS group (P = .001). Diaphragmatic excursion during calm and deep breathing remained similar pre- and postoperatively in both groups (P=.674 and P=.399, respectively). Tumor resection rates and postoperative neurological deficits were also similar (P=.838 and P=.523, respectively).

The RS group experienced fewer intraoperative spontaneous movements (0% vs 21%, P=.047) and less brain swelling. Incidence of coughing and xerostomia did not differ significantly (P>.05).[26]

Impact of extubation depth on emergence agitation and hemodynamic stability after nasal surgery

Suo L et al., study demonstrated as a prospective, randomized controlled trial (NCT04844333) was conducted at Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital with ethical approval (SH9H-2020-T414-2) granted on 25/02/2021. Patients aged 18-60 years with ASA physical status I-II, scheduled for elective nasal surgery under GA between May 2021 and April 2022, were recruited. Written informed consent was obtained. Exclusion criteria included mental, neurological, pulmonary, cardiovascular, hepatic, renal disorders, chronic pain, drug or alcohol abuse, pregnancy, epilepsy, obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m²), sleep apnea, and any conditions deemed unsuitable by investigators.

Patients were monitored for heart rate (HR), arterial blood pressure (ABP), peripheral arterial oxygen saturation (SpO₂), and bispectral index (BIS). Standard induction included midazolam, fentanyl, propofol, and rocuronium, followed by intubation. Anaesthesia was maintained with intravenous (IV) propofol (2-15 mg/kg/h) and remifentanil (0.05-2 µg/kg/min), targeting BIS 40-60. No inhalational agents were used.

Post-surgery, patients were randomized (1:1) into Group A (awake extubation) or Group D (deep extubation with continued propofol 2-4 mg/kg/h). Extubation criteria differed between groups but included stable vital signs, respiratory function, and consciousness (Group A). Monitoring continued in the Post-Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU) at T1-T5 (end of surgery to 90 min). Parameters recorded included SpO₂, HR, BP, BIS, VAS, time to spontaneous respiration, extubation time, PACU stay, agitation episodes, and adverse events.

Randomization was via SAS 9.2 with a block size of 4 and allocation concealed in sequential envelopes opened post-surgery. The primary outcome was EA incidence during T1-T5. Secondary outcomes included recovery times, adverse events, and vital sign trends. Sample size was calculated at 202 (91 per group + 10% dropout) based on expected EA rates (30% vs. 50%).

A total of 202 patients were enrolled and randomized equally into deep extubation (Group D) and awake extubation (Group A) groups. Fifteen were excluded due to failure to meet extubation conditions, resulting in 187 patients for analysis (Group D: n=95; Group A: n=92). Baseline characteristics were generally balanced between groups, with the only significant differences observed in surgery type and remifentanil dosage.

EA occurred in 53.5% of all patients but was significantly less frequent in Group D than in Group A (34.7% vs. 72.8%, P<0.001). RASS and Ramsay scores at T2–T4 supported a lower agitation level and higher sedation in Group D. Group D also had longer spontaneous respiration recovery and extubation times than Group A (P=0.010 and P=0.008, respectively). No differences were observed in pain scores.

Vital signs showed less fluctuation in mean arterial pressure (MAP) in Group D, particularly at T1-T3. BIS values were lower in Group D at T2 and T3. SpO2 and HR showed no significant intergroup differences. Adverse events in the PACU, including airway obstruction, respiratory depression, bradycardia, and blood pressure abnormalities, did not significantly differ between groups. No serious complications were reported, indicating both extubation methods were safe and well tolerated.[27]

Airway anaesthesia techniques: A comparative study of block and nebulization methods

In Chavan G., a prospective, randomized crossover study was conducted at the Oncosurgery OT of a medical college hospital in India from April 2017 to April 2018, following approval by the Institutional Ethics Committee. Sixty cooperative adults aged 18-80 years, classified as ASA I–II and scheduled for wide local excision and neck dissection for intraoral malignancies, were enrolled. Exclusion criteria included unwillingness, allergy to local anesthetics, hematologic or psychiatric disorders, and tumors involving the posterior third of the tongue, tonsils, or larynx.

All participants underwent thorough preoperative assessment, including airway evaluation. Standard fasting guidelines and anti-aspiration prophylaxis (IV ranitidine 50 mg) were followed. Informed consent was obtained after explaining the awake fiberoptic bronchoscope (FOB)-guided intubation procedure in the patient’s native language.

Standard monitors were applied. Premedication included glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg, midazolam 1 mg, and fentanyl 50 mcg IV. FOB was performed using a preloaded flexometallic ETT (7.5 mm for females, 8.0 mm for males). Parameters assessed included intubation time, intubation score, patient comfort score, and complications. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0; P<0.05 was considered significant.

A total of 60 patients were randomized into the Airway Nebulization (AN) and Airway Block (AB) groups (n=30 each). Demographic parameters, Mallampati scores, mouth opening, thyromental distance, and neck movements were comparable between the groups. Hemodynamic parameters, including heart rate and blood pressure, remained stable across both groups, with no significant intergroup differences. However, a transient drop in SpO₂ to 95% was observed in the AN group during and after passage through the vocal cords. Two patients in the AN group developed laryngospasm and required conversion to GA.

Total intubation time was significantly shorter in the AB group (200 ± 146.35 sec) compared to the AN group (266.62 ± 115.86 sec; P<0.05). The time from the nasopharynx to the trachea was notably longer in the AN group. Intubation scores were optimal in 90% of patients in the AB group versus 36% in the AN group. Patient comfort during fiberoptic intubation was significantly better in the AB group, with higher frequencies of “no reaction” and “cooperative” scores on the 5-point and 3-point scales, respectively (p<0.01). The AB technique demonstrated superior efficacy, patient comfort, and fewer complications.[28]

Clinical outcomes of two SLN block approaches in difficult airway management

Study by Shan T. et al., a single-center, randomized, prospective study was conducted at Nanjing First Hospital, approved by the ethics committee (KY20220425-01) and registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2200061287). Written informed consent was obtained. Fifty patients (age 18-65, weight 45-80 kg, ASA I–II) undergoing elective abdominal/orthopedic surgery with anticipated difficult airways were enrolled. Exclusion criteria included infection at the puncture site, local anaesthetic allergy, or anticoagulant use. Patients were randomly assigned to receive ultrasound-guided superior laryngeal nerve (SLN) block via parasagittal (PS) or transverse (T) approach. Block techniques used 2 mL of 2% lidocaine bilaterally.

Preoperatively, all patients fasted and received 0.5 mg penehyclidine IM. Monitoring included ECG, SpO₂, BP, and radial artery catheterization. Sedation was achieved with midazolam (0.03 mg/kg) and sufentanil (0.1 µg/kg). Supplemental oxygen was administered via nasal cannula. Topical anaesthesia included 2.4% lidocaine spray (32 mg total) and a transtracheal injection of 3 mL 2% lidocaine. Fiberoptic-guided nasotracheal intubation was performed using 7.5 mm (males) or 7.0 mm (females) reinforced tubes. The anesthesiologist performing intubation was blinded to group allocation.

Primary outcome: quality of airway anesthesia (5-point scale). Secondary outcomes: tube tolerance (1-3 scale), time to identify landmarks, anesthetic administration, total time, MAP and HR at four time points (T0-T3), Ramsay sedation score (1-6), incidence of sore throat (1 h, 24 h), and hoarseness (pre-intubation, 1 h, 24 h). Sample size was calculated with PASS 15.0; 50 patients were enrolled to accommodate potential dropout. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22.

Fifty patients were randomly assigned to the PS group (n=25) and the transverse (T) group (n=25). Baseline demographics such as age (46.1 ± 8.1 vs. 45.9 ± 9.7 years), sex (F/M: 15/10 in both), BMI (24.6 ± 2.8 vs. 23.5 ± 3.6 kg/m²), and ASA status were comparable (P> 0.05). All patients underwent awake orotracheal intubation. Airway anaesthesia quality was significantly better in the PS group (median grade 0 (0-1) vs. 1 (0-1), P=0.036), with 72% experiencing no gagging/coughing vs. 44% in the T group. Tube tolerance score was significantly lower in the PS group (1 (1) vs. 1 (1-1.5), P=0.042), with 96% showing good cooperation compared to 76% in the T group.

Time to identify the nerve was significantly shorter in the PS group (18 (16-19) vs. 88 (59-132) sec, P<0.001). Total procedure time was also shorter (113 (98.5-125.5) vs. 188 (149.5-260) sec, P<0.001). The performance time showed no significant difference. Hemodynamic variables and Ramsay sedation scores showed no significant differences between groups at all measured time points (P>0.05). The incidence of sore throat at 24 hours was significantly lower in the PS group (8% vs. 36%, P=0.041). However, hoarseness before intubation was higher in the PS group (72% vs. 40%, P=0.023). No significant differences were observed at 1 or 24 hours post-extubation.[29]

Effect of nebulization parameters on patient tolerance and anaesthetic efficiency in awake intubation

A study conducted by Li C et al., a randomized, double-blind trial, was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Henan Provincial People’s Hospital (2020 Ethics No. 136) and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Patients aged 18–65 years with ASA status I–III requiring awake tracheal intubation (ATI) were recruited between September 2024 and January 2025. Inclusion criteria involved patients with known or suspected difficult airways based on medical history or physical examination. Exclusion criteria included refusal, airway bleeding, or allergy to local anesthetics. Participants were randomized equally into four groups (A3, A6, A9, A11) via SAS 9.4 to receive 20 mL of 2% lidocaine via vibrating mesh nebulizers generating particle sizes of 3-4, 6-7, 9-10, and 11-12 μm, respectively. Randomization and allocation concealment were performed using a web-based system. Patients, observers, outcome assessors, and statisticians were blinded to group assignments.

Preoperative assessments included airway examination and monitoring setup. Intravenous penehyclidine hydrochloride and midazolam were administered before topical anaesthesia. After nebulization, dexmedetomidine and remifentanil provided sedation. Additional lidocaine sprays were used if discomfort persisted. Tracheal intubation was performed under video laryngoscopy, and airway responses and hemodynamics were recorded. The primary outcome was cough score during intubation. Secondary outcomes included reaction/discomfort scores, hemodynamics, nebulization time, lidocaine sprays used, and vomiting. A sample of 54 patients per group (216 total) was determined via power analysis. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 21.0 with significance set at P< 0.05.

A total of 230 patients were recruited between September 2024 and January 2025. Following exclusions for protocol violations, 211 participants were randomized into four groups: A3, A6, A9, and A11. After further exclusions, 184 patients were included in the final analysis: A3 (n=42), A6 (n=51), A9 (n=51), and A11 (n=40). Particle sizes (V50) closely matched intended distributions: A3 (3.61 μm), A6 (6.53 μm), A9 (9.19 μm), A11 (11.94 μm). Cough, reaction, and discomfort scores showed significant intergroup differences (P=0.021, P=0.036, and P=0.017, respectively). A9 group demonstrated the best comfort with significantly lower scores compared to A3 (cough: P=0.005; reaction: P=0.024; discomfort: P=0.003). A6 also outperformed A3 in cough scores (P=0.036), and A11 showed lower reaction scores than A3 (P=0.011).

Nebulization time varied significantly across groups (P<0.001), with A3 having the longest duration (3605.9 ± 316.5 s), compared to A6 (748.2 ± 75.6 s), A9 (529.8 ± 51.7 s), and A11 (452.1 ± 67.3 s). Hemodynamic parameters were mostly comparable, but HR increases were significantly smaller in the A6 and A9 groups at various intubation stages compared to A3.[30]

| Study | Design & population | Groups/interventions | Primary outcomes | Key findings | Notable adverse events |

| Chen Y et al. Awake Surgery (AC) |

RCT, single-blind, 42 patients undergoing AC for supratentorial lesions | RS group (rocuronium-sugammadex) vs. nRS (no muscle relaxant) | Awake time, arousal quality | The RS group had shorter arousal time (13.5 vs. 21 min, P<0.01); similar arousal quality, nausea, seizures, or shivering. | Fewer LMA adjustments (P=0.001) and spontaneous movements (P=0.047) in RS; brain swelling lower |

| Suo L et al. Nasal Surgery Extubation | RCT, 187 patients (ASA I–II) | Group A: Awake extubation; Group D: Deep extubation (propofol maintained) | Emergence agitation (EA) incidence | EA was significantly lower in Group D (34.7% vs. 72.8%, P<0.001); there was a slower recovery in Group D. | Stable hemodynamics; no major differences in SpO₂, HR; safe outcomes for both |

| Chavan G. Airway anesthesia technique | Prospective crossover, 60 patients for intraoral surgery | Airway block (AB) vs. Airway nebulization(AN) | Intubation time, intubation score, and patient comfort | AB group had shorter intubation time (P<0.05); better comfort & intubation scores (P<0.01) | 2 laryngospasms in the AN group requiring conversion to GA |

| Shan T. et al. SLN Block Approach |

RCT, 50 patients with a difficult airway | Parasagittal (PS) vs. Transverse (T) SLN block | Airway anesthesia quality, tube tolerance | PS group had better anesthesia quality (P=0.036), higher cooperation (96% vs. 76%), shorter procedure time (P<0.001) | Higher hoarseness pre-intubation in PS (P=0.023), lower sore throat at 24h (P=0.041) |

| Li C. et al. Nebulization parameters | RCT, double-blind, 184 patients for ATI | Groups A3, A6, A9, A11 (particle sizes 3-12 μm) | Cough score (primary), reaction/discomfort, hemodynamics | A9 had the lowest cough, discomfort, and reaction scores (P<0.05); A6 and A11 also had better scores than A3 | A3 had longest nebulization time (~60 mins); A9 and A6 had better HR control during intubation |

Table 1: Summary of comparative outcomes in anaesthetic approaches

Discussion

Awake surgery anaesthesia continues to evolve as a key advancement in neurosurgical and high-risk procedures, offering a balance between patient safety, functional preservation, and perioperative efficiency. The study by Chen Y et al. demonstrates the advantages of incorporating rocuronium-sugammadex (RS) in AC, achieving significantly shorter arousal times (13.5 vs. 21 min, P < .01) and reduced spontaneous movements (0% vs. 21%, P = .047), with comparable resection rates and adverse events. These findings emphasize the value of refined sedation and airway strategies in enhancing surgical workflow and patient outcomes.

Similarly, Suo L et al. highlighted how deep extubation significantly lowered emergence agitation rates (34.7% vs. 72.8%, P < .001) in nasal surgeries without compromising safety, albeit with delayed respiratory recovery. This supports individualized extubation strategies to minimize postoperative agitation.

In difficult airway scenarios, multiple studies demonstrated the superiority of targeted regional airway anaesthesia. Chavan G. showed that airway block (AB) yielded shorter intubation times, better patient comfort, and fewer complications than nebulization. Shan T. et al. further confirmed the parasagittal SLN block’s superiority in quality, efficiency, and reduced sore throat incidence. Complementing these, Li C. et al. found that intermediate particle sizes (9-10 µm) during nebulization significantly reduced cough and discomfort during awake intubation, optimizing patient tolerance.

Collectively, these findings underscore the necessity of tailoring anaesthetic strategies based on procedure type, patient comorbidities, and airway complexity, leveraging pharmacological advances and technique modifications to improve outcomes and perioperative experience in awake surgery contexts.

Conclusion

Awake surgery anaesthesia offers significant advantages across neurosurgical, thoracic, and airway-related procedures, including:

- Shorter arousal times with neuromuscular block reversal (e.g., rocuronium-sugammadex)

- -Reduced emergence agitation with deep extubation strategies

- Improved intubation success and patient comfort using superior laryngeal nerve blocks or airway blocks

- Optimal nebulization particle size (9–10 μm) resulting in less airway reactivity and better tolerance

In patients with anticipated difficult airways, the use of precise regional anaesthesia techniques improves intubation quality and patient comfort. Chavan G. demonstrated that airway blocks outperform nebulization in terms of intubation success, patient cooperation, and complication rates. Shan T. et al. confirmed that parasagittal SLN blocks provide better airway anaesthesia and reduced sore throat incidence, while Li C. et al. found that lidocaine particle size significantly affects tolerability, with 9-10 μm offering optimal patient response and minimal side effects.

These techniques reduce the risks associated with GA, particularly in high-risk populations, and allow real-time assessment of neurological function. Further high-quality, multicenter trials are needed to validate these approaches and develop standardized protocols.

References

- Özlü O. Anaesthesiologist’s approach to awake craniotomy. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim. 2018;46(4):250-256. doi:10.5152/TJAR.2018.56255 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kim SH, Choi SH. Anesthetic considerations for awake craniotomy. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul). 2020;15(3):269-274. doi:10.17085/apm.20050 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sairyo K, Chikawa T, Nagamachi A. State-of-the-art transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic lumbar surgery under local anesthesia: Discectomy, foraminoplasty, and ventral facetectomy. J Orthop Sci. 2018;23(2):229-236. doi:10.1016/j.jos.2017.10.015 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lim WY, Wong P. Awake supraglottic airway guided flexible bronchoscopic intubation in patients with anticipated difficult airways: a case series and narrative review. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2019;72(6):548-557. doi:10.4097/kja.19318 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mugnaini G, Tombelli S, Burlone A, et al. Awake thoracic surgery for lung cancer treatment: where we are and future perspectives-our experience and review of literature. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2025;20(1):62. doi:10.1186/s13019-024-03313-6 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Potters JW, Klimek M. Local anesthetics for brain tumor resection: Current perspectives. Local Reg Anesth. 2018;11:1-8. doi:10.2147/LRA.S135413 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hans P, Bonhomme V. Anesthetic management for neurosurgery in awake patients. Minerva Anestesiol. 2007;73(10):507-512. Anesthetic management for neurosurgery in awake patients

- Conte V, Baratta P, Tomaselli P, Songa V, Magni L, Stocchetti N. Awake neurosurgery: An update. Minerva Anestesiol. 2008;74(6):289-292. Awake neurosurgery: an update

- Min KT. Practical guidance for monitored anesthesia care during awake craniotomy. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul). 2025;20(1):23-33. doi:10.17085/apm.24183 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Murselović T, Makovšek A. Airway management in neuroanesthesia. Acta Clin Croat. 2023;62(Suppl 1):119-124. doi:10.20471/acc.2023.62.s1.15 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Izzo A, Piano C, D’Ercole M, et al. Intraoperative microelectrode recording during asleep deep brain stimulation of subthalamic nucleus for Parkinson Disease. A case series with systematic review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev. 2024;47(1):342. doi:10.1007/s10143-024-02563-1 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Duarte-Gamas L, Pereira-Neves A, Sousa J, Sousa-Pinto B, Rocha-Neves J. The Diagnostic Accuracy of Intra-Operative Near Infrared Spectroscopy in Carotid Artery Endarterectomy Under Regional Anaesthesia: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2021;62(4):522-531. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2021.05.042 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Fiani B, Reardon T, Selvage J, et al. Awake spine surgery: An eye-opening movement. Surg Neurol Int. 2021;12:222. doi:10.25259/SNI_153_2021 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Uribe AA, Stoicea N, Echeverria-Villalobos M, et al. Postoperative nausea and vomiting after craniotomy: An evidence-based review of general considerations, risk factors, and management. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2021;33(3):212-220. doi:10.1097/ANA.0000000000000667 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Evidente VGH, Ponce FA, Evidente MH, et al. Adductor Spasmodic Dysphonia Improves with Bilateral Thalamic Deep Brain Stimulation: Report of 3 Cases Done Asleep and Review of Literature. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2020;10:60. doi:10.5334/tohm.575 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lee KS, Yordanov S, Stubbs D, et al. Integrated care pathways in neurosurgery: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0255628. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0255628 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Syrous NS, Sundstrøm T, Søfteland E, Jammer I. Effects of intraoperative dexmedetomidine infusion on postoperative pain after craniotomy: A narrative review. Brain Sci. 2021;11(12):1636. doi:10.3390/brainsci11121636 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- de Gray LC, Matta BF. Acute and chronic pain following craniotomy: A review. Anaesthesia. 2005;60(7):693-704. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.03997.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Luo Z, Jiao B, Zhao H, Huang T, Zhang G. Comparison of retrograde intrarenal surgery under regional versus general anaesthesia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2020;82:36-42. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.08.012 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gandhe RU, Bhave CP. Intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging for neurosurgery-An anaesthesiologist’s challenge. Indian J Anaesth. 2018;62(6):411-417. doi:10.4103/ija.IJA_29_18 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- McPhaden E, Tobias JD, Smith A. Clinical experience with remimazolam in neuroanesthesiology and neurocritical care: An educational focused review. J Clin Med Res. 2025;17(3):125-135. doi:10.14740/jocmr6193 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Li Y, Wu J, Chen C, Su C. Effects of spinal-epidural anesthesia combined with intravenous etomidate on adrenocortical and immune stress in elderly patients undergoing anorectal surgery: A retrospective analysis. Biomol Biomed. 2025;25(3):701-707. doi:10.17305/bb.2024.10759 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Zhang Y, Liu T, Zhou Y, Yu Y, Chen G. Analgesic efficacy and safety of erector spinae plane block in breast cancer surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Anesthesiol. 2021;21(1):59. doi:10.1186/s12871-021-01277-x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wang H, Huang X, Wu A, Li Q. Management of anesthesia in a patient with osteogenesis imperfecta and multiple fractures: a case report and review of the literature. J Int Med Res. 2021;49(6):3000605211028420. doi:10.1177/03000605211028420 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Deng J, Liu J, Rong D, et al. A meta-analysis of locoregional anesthesia versus general anesthesia in endovascular repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2021;73(2):700-710. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2020.08.112 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Chen Y, Yang R, Sun M, et al. The efficacy and safety of using a combination of rocuronium and sugammadex for awake craniotomy anesthesia: A randomized clinical trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103(12):e37436. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000037436 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Suo L, Lu L, Li J, et al. The effect of deep and awake extubation on emergence agitation after nasal surgery: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024;24(1):177. doi:10.1186/s12871-024-02565-y PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Chavan G, Chavan AU, Patel S, Anjankar V, Gaikwad P. Airway Blocks Vs LA Nebulization- An interventional trial for Awake Fiberoptic Bronchoscope assisted Nasotracheal Intubation in Oral Malignancies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020;21(12):3613-3617. doi:10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.12.3613 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Shan T, Tan Q, Wu D, et al. Ultrasound-guided superior laryngeal nerve block: a randomized comparison between parasagittal and transverse approach. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024;24(1):269. doi:10.1186/s12871-024-02612-8 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Li C, Sun M, Zhang L, et al. Nebulization with differently sized 2% lidocaine atomized particles in awake tracheal intubation by video laryngoscopy: a proof-of-concept randomized trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2025;25(1):321. doi:10.1186/s12871-025-03178-9 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not applicable

Funding

No funding

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Samatha Ampeti

Department of Pharmacology

Kakatiya University, University College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Warangal, TS, India

Email: ampetisamatha9@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Shubham Ravindra Sali, Mansi Srivastava, Raziya Begum Sheikh, Sonam Shashikala B V, Patel Nirali Kirankumar

Independent Researcher, Department of Content

medtigo India Pvt Ltd, Pune, India

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing, original draft preparation, and writing review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest Statement

None

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Shubham RS, Samatha A, Mansi S, Raziya BS, Sonam SBV, Patel NK. Awake Anaesthesia in High-Risk Surgeries: A Systematic Review of Techniques, Airway Management, and Patient Outcomes. medtigo J Anesth Pain Med. 2025;1(2):e3067124. doi:10.63096/medtigo3067124 Crossref