Author Affiliations

Abstract

Anti-synthetase antibody syndrome (ASA) is a rare and complex immune-mediated condition that presents in various ways. It is diagnosed by antibodies against aminoacyl tRNA synthetase, with anti-JO-1 being the most common. The clinical features include myositis, interstitial lung disease (Non-Specific Interstitial Pneumonitis (NSIP) pattern), non-erosive arthritis, unexplained recurrent fever, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and mechanic’s hands, primarily affecting the skin, respiratory, and musculoskeletal systems. We present a case of a 37-year-old woman who experienced multiple hospital admissions due to symmetrical, progressive polyarthritis affecting both large and small joints. This was accompanied by morning stiffness that was temporarily relieved by medication, followed by respiratory symptoms such as intermittent cough, fever, shortness of breath, exertional dyspnea, and cracks on her fingers (mechanic’s hands). Over time, her symptoms gradually worsened, impacting her daily activities like combing her hair and changing clothes, and causing debilitating exertional dyspnea after just a few steps, significantly diminishing her quality of life. A thorough workup revealed positive anti-histidyl-transfer RNA synthetase (Anti-Jo-1) and anti–Sjögren’s-syndrome-related antigen A (Anti-SSA/Ro) antibodies, elevated creatine phosphokinase (CPK) and serum aldolase levels, and high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) chest imaging indicative of interstitial lung disease, likely NSIP. Antinuclear antibody (ANA) was negative, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels were normal, and a bronchial biopsy showed benign respiratory mucosa with no signs of malignancy. The patient was diagnosed with anti-synthetase antibody syndrome and began pulse therapy with methylprednisolone. This article discusses the clinical manifestations, diagnostic criteria, treatment options, disease progression, and prognosis associated with this condition.

Keywords

Anti-synthetase antibody syndrome, Mechanic’s hands, Interstitial lung disease, Antibodies, Non-specific interstitial pneumonitis.

Introduction

Anti-synthetase antibody syndrome, a subtype of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIMs), a rare multisystem disease, consists of a triad of muscle inflammation(myositis), multiple joint involvement(polyarthritis), and progressive inflammation and scarring of the lung (interstitial lung disease).[1] Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies include polymyositis, dermatomyositis, myositis overlap syndrome, immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy, and inclusion body myositis (IMS).[2] Autoantibodies against enzymes characterize ASA, i.e., aminoacyl tRNA synthetases or ASA.[3] These enzymes play a role in protein synthesis by linking specific amino acids to their respective t RNA molecules.[4] The most common antibodies in ASA are Anti Jo-1, targeted against anti-histidyl t RNA, then followed by anti-PL-7 (threonyl), anti-PL-12 (alanyl), anti-EJ (glycyl), anti-OJ (isoleucyl), anti-KS (asparaginyl), anti-Zo (phenylalanyl), and anti-Ha (tyrosyl).[5]

The epidemiology of Antisynthetase Antibody Syndrome (ASA) remains unclear. A study in Manchester revealed a mean incidence of IIM of 17.6/1,000,000 person-years, with 28% identified as ASA. Females are more affected than males, and the mean age at onset ranges from 43 to 60 years. Black patients may have more frequent and severe interstitial lung disease (ILD), but ASA epidemiology is not influenced by ethnicity. Older studies with varying disease definitions, failure to include antisynthetase antibodies, and lack of data-driven classification criteria have impacted reported epidemiology. [1,3,6] Moreover, complete clinical manifestations are not seen in all patients, making diagnosis difficult and delayed.

The symptoms range from a triad of myositis, polyarthritis, and ILD to other non-specific symptoms like mechanic’s hand, Raynaud disease, unexplained fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, unintended weight loss, along with some experiencing dry eyes, dry mouth, dysphagia, overlapping with symptoms of other autoimmune diseases.[7] Pulmonary involvement is seen in 90-95% of patients, with ILD being associated with severity and worsening prognosis of the disease.[8]

Only 5% of the AENEAS cohort had the traditional triad of ILD, myositis, and arthritis, which included patients with anti-Jo1, anti-PL7, anti-PL12, anti-EJ, and anti-OJ antibodies. [9] ILD onset is primarily a single triad feature in all included antibody groupings, indicating that the disorder can frequently manifest as isolated ILD, myopathy, or arthritis.[10] During the follow-up period, many patients in the AENEAS cohort developed new clinical characteristics. Cough and dyspnea are the most common symptoms of pulmonary illness, which affects 67 to 100% of people with ASA. According to specific findings, anti-PL7 and anti-PL12 positive patients have a higher prevalence of ILD than anti-Jo1, who are more commonly encountered.[11] ILD is detected in 82% of anti-Jo1 patients at follow-up, with 20.8% asymptomatic. The presentation of ILD in the disease course might vary, with pulmonary symptoms emerging early, developing concurrently with other symptoms, or appearing later in the disease.[12] Patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis are more likely to be male and older at onset than those with ASA and other connective tissue disease-associated ILD. Pleural involvement has been observed in ASA, with 42.2% having pleural effusions. The 6-minute walk test can be used to monitor and quantify performance status, using saturation probe measurements to identify drops in oxygen saturation.[13,14]

We present a case of a female with progressive non-erosive polyarthritis and other non-specific symptoms along with lung involvement. Informed consent was obtained from the patient to present and study her unusual clinical manifestations.

Case Presentation

A 37-year-old woman was admitted to the outpatient department with symptoms of fever, increasing shortness of breath, and rheumatoid arthritis, along with joint pain deterioration for the last year. Her chronic physical history calls for polyarticular, symmetrical pain in the joints that initially set in ten years back, the large joints, such as the knees and the wrists, and then spread to the smaller joints and the temporomandibular joint. These symptoms were treated with medication temporarily.

In 2019, she was hospitalized with suspected COVID-19, but it turned out to be pneumonia, which led to multiple subsequent hospital visits due to persistent respiratory symptoms and joint pain. She was later diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis and started on steroid treatment. However, about a year ago, her joint pain worsened significantly, accompanied by morning stiffness, challenges with daily activities, and severe shortness of breath even with minimal exertion, which led to further investigations. Six to seven months ago, she was diagnosed with interstitial lung disease and polymyositis.

On the general physical examination, her vital signs were recorded as BP 130/80 mmHg, a temperature of 101°F, and a SpO2 level of 92% while on room air. The musculoskeletal examination showed synovitis in the wrists and metacarpophalangeal joints, along with proximal myopathy (Figures 01 & 02).

Figure 1: Peeling and cracks in the mechanic’s hands

Figure 2: Hyperkeratosis, peeling, and cracks in the mechanic’s hand

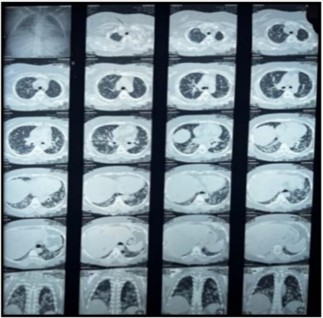

Bilateral coarse crackles were noted upon chest auscultation, suggesting possible interstitial lung involvement. A comprehensive set of laboratory tests was performed. The results indicated significantly elevated CPK levels at 1250 U/L (normal range: 20-75 U/L), and a serum aldolase level of 10 U/L (normal: <7.60 U/L). The ENA profile was particularly noteworthy for positive Anti-Jo-1 antibodies (96 U/L, normal: 6-12 U/L) and Anti-SSA/Ro 52 antibodies (67 U/L, normal: 6-12 U/L), while the remainder of the ENA profile, including rheumatoid factor (10 U/L), ANA, and anti-CCP, returned negative results. HRCT chest showed features of interstitial lung disease consistent with a NSIP pattern, including bilateral ground-glass opacities more pronounced in the lower lobes, interstitial septal thickening, and increased attenuation in a reticular pattern, with preserved lung volumes and no honeycombing (Figure 03). ACE levels were within normal limits at 32.4 U/L (normal: 8-65 U/L). Bronchial biopsy indicated benign respiratory mucosa with no malignancy, and echocardiography demonstrated normal biventricular systolic function with an ejection fraction of 62%.

Figure 3: HRCT Chest: NSIP pattern with bilateral ground-glass opacities, interstitial septal thickening, and reticular attenuation

Polymyositis, dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis with pulmonary involvement, systemic Lupus erythematosus (SLE), and scleroderma were all explored as alternative diagnoses. Muscle weakness, increased CPK, and positive anti-Jo-1 antibodies all contributed to polymyositis. Dermatomyositis was considered due to muscle involvement but ruled out due to the absence of skin abnormalities. Rheumatoid arthritis with lung involvement was considered due to joint pain and increased markers. Scleroderma was hypothesized based on symptoms such as Raynaud’s and mechanic’s hands, but negative antibodies and skin involvement lowered the possibility.

Case Management

The patient’s treatment regimen was initiated with prednisolone at a dosage of 1mg/kg/day. Concurrently, she began monthly pulse cyclophosphamide therapy at a 1 G intravenous monthly dose, scheduled for six months to manage the underlying condition. To prevent Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, a common risk associated with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide therapy, prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was also prescribed. Supportive care included antibiotics to manage any infections. Ten days following the first cycle of cyclophosphamide, the patient was successfully weaned off oxygen support. After induction therapy, she was put on azathioprine as maintenance therapy. Since that time, she has maintained stability and has not required further respiratory assistance.

Discussion

Diagnosing anti-synthetase antibody syndrome can be challenging due to the varied and often vague clinical signs associated with this rare autoimmune disorder.[3,4] As seen in this case, individuals with ASS may exhibit a wide array of symptoms, such as myositis, ILD, arthritis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and even general symptoms like fever and malaise. This diversity in clinical features and the gradual onset and evolution of symptoms over time can significantly hinder timely recognition and diagnosis.[7]

The exact cause of the disease remains unclear. Still, it is thought to involve the activation of both innate and adaptive immune systems, producing autoantibodies that target aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Notable autoantibodies, including anti-Jo-1, anti-PL-7, and anti-PL-12, are considered key indicators of the disease and can be essential for diagnosis.[8,15]

In this case, the patient’s clinical journey was marked by a complex and changing presentation. Initially, the patient experienced polyarticular, symmetrical joint pain, which was soon followed by respiratory problems, interstitial lung disease, and weakness in the proximal muscles. Key diagnostic indicators included elevated creatine phosphokinase (CPK) levels, positive anti-Jo-1 and anti-SSA/Ro 52 antibodies, along with HRCT findings suggestive of interstitial lung disease, likely nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, which pointed towards the possibility of ASS.[13,14] The differential diagnoses were thoroughly assessed, including polymyositis, dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis with lung involvement, systemic lupus erythematosus, and scleroderma. The absence of distinctive skin symptoms and negative anti-CCP antibodies helped eliminate dermatomyositis and rheumatoid arthritis from consideration. The negative ANA and specific autoantibodies also made systemic lupus erythematosus and scleroderma less probable.[16-18]

| S. No. | Connors et al. 2010 |

Solomon et al. 2011 |

EULAR/ACR 2017 |

| 1 | SPECIFIC: ASA antibody

+ 1 of the following |

SPECIFIC: ASA antibody

+ 2 Major or 1 Major and two minor criteria |

Specific: IIM Score of 7.5(8.7 with muscle biopsy)

Probable: IIM Score of 5.5(6.7 with muscle biopsy |

| 2 | Myositis or polydermatositis by Bohan and Peter

ILD Arthritis Raynaud’s phenomenon Fever Mechanics hands |

Major criteria:

Minor criteria:

|

Anti-jo 1

Symmetric proximal weakness in upper and lower limbs Proximal leg muscle weakness is more pronounced Dysphagia or esophageal motility disorders Skin involvement (Gottrons papules, heliotrope rash) Age at onset Raised skeletal muscle markers and typical features in muscle biopsy |

Table 1Comparison of diagnostic criteria of ASA and EULAR/ACR criteria for IIM

This case highlights the necessity of a detailed clinical approach and the awareness of atypical signs and symptoms when diagnosing ASA. A multidisciplinary team, including rheumatologists, pulmonologists, and other specialists, must navigate the complex clinical picture and reach an accurate diagnosis. Recognizing the condition early and starting appropriate treatment promptly, as shown in this case with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide, can significantly improve management and outcomes for patients with ASS. This underscores the importance of raising awareness among healthcare providers about the various manifestations of this rare condition, which can lead to earlier diagnoses and more effective treatment strategies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, ASA should be considered in patients with unexplained ILD and related symptoms. ILD in ASA is often severe and linked to poor outcomes, especially with Anti-SSA/Ro 52 antibodies. Early diagnosis and a multidisciplinary approach are crucial, with treatment mainly involving corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs, as targeted therapies are not yet available.

References

- Wells M, Alawi S, Thin KYM, et al. A multidisciplinary approach to the diagnosis of antisynthetase syndrome. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:959653. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.959653

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Patel P, Marinock JM, Ajmeri A, Brent LH. A Review of Antisynthetase Syndrome-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(8):4453. doi:10.3390/ijms25084453

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Elsayed M, Abdelgabar A, Karmani J, Majid M. A Case of Antisynthetase Syndrome Initially Presented With Interstitial Lung Disease Mimicking COVID-19. J Med Cases. 2023;14(1):25-30. doi:10.14740/jmc4031

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Lima Corrêa de Araújo B, Victor DR, Farias Fontes HM, Caminha Mendes Gomes RM, Lima Corrêa de Araújo L. Antisynthetase Syndrome With Predominant Pulmonary Involvement: A Case Report. Cureus. 2023;15(8):e43966. doi:10.7759/cureus.43966

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - De Andrade VP, Miossi R, De Souza FH, Shinjo SK. Anti-Ha Antisynthetase Syndrome: A Case Report. Cureus. 2024;16(5):e61251. doi:10.7759/cureus.61251

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Patel P, Marinock JM, Ajmeri A, Brent LH. A Review of Antisynthetase Syndrome-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(8):4453. doi:10.3390/ijms25084453

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Aslam M, Khan S, Batool W, Ali Z, Hanif IM. Anti-synthetase Syndrome: A Diagnostic Dilemma. Cureus. 2023;15(3):e36760. doi:10.7759/cureus.36760

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Elsayed M, Abdelgabar A, Karmani J, Majid M. A Case of Antisynthetase Syndrome Initially Presented With Interstitial Lung Disease Mimicking COVID-19. J Med Cases. 2023;14(1):25-30. doi:10.14740/jmc4031

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Cavagna L, Trallero-Araguás E, Meloni F, et al. Influence of Antisynthetase Antibodies Specificities on Antisynthetase Syndrome Clinical Spectrum Time Course. J Clin Med. 2019;8(11):2013. doi:10.3390/jcm8112013

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Jiang M, Dong X, Zheng Y. Clinical characteristics of interstitial lung diseases positive to different anti-synthetase antibodies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(19):e25816. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000025816

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - González-Pérez MI, Mejía-Hurtado JG, Pérez-Román DI, et al. Evolution of Pulmonary Function in a Cohort of Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease and Positive for Antisynthetase Antibodies. J Rheumatol. 2020;47(3):415-423. doi:10.3899/jrheum.181141

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Masiak A, Marzec M, Kulczycka J, Zdrojewski Z. The clinical phenotype associated with antisynthetase autoantibodies. Reumatologia. 2020;58(1):4-8. doi:10.5114/reum.2020.93505

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Barratt SL, Morales M, Speirs T, et al. Specialist palliative care, psychology, interstitial lung disease (ILD) multidisciplinary team meeting: a novel model to address palliative care needs. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2018;5(1):e000360. doi:10.1136/bmjresp-2018-000360

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Badshah A, Haider I, Pervez S, Humayun M. Antisynthetase syndrome presenting as interstitial lung disease: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2019;13(1):241. doi:10.1186/s13256-019-2146-0

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Galindo-Feria AS, Notarnicola A, Lundberg IE, Horuluoglu B. Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases: On Anti-Synthetase Syndrome and Beyond. Front Immunol. 2022;13:866087. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.866087

Crossref | Google Scholar - Moghadam-Kia S, Oddis CV, Aggarwal R. Approach to asymptomatic creatine kinase elevation. Cleve Clin J Med. 2016;83(1):37-42. doi:10.3949/ccjm.83a.14120

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Gomes Ferreira S, Fernandes L, Santos S, Ferreira S, Teixeira M. From Suspected COVID-19 to Anti-synthetase Syndrome: A Diagnostic Challenge in the Pandemic Era. Cureus. 2024;16(1):e52733. doi:10.7759/cureus.52733

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Rojas-Serrano J, Herrera-Bringas D, Mejía M, Rivero H, Mateos-Toledo H, Figueroa JE. Prognostic factors in a cohort of antisynthetase syndrome (ASS): serologic profile is associated with mortality in patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD). Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34(9):1563-1569. doi:10.1007/s10067-015-3023-x

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

None

Funding

None

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Fatima Khurshid

Department of Radiation Oncology

Shifa International Hospitals Limited, Islamabad, Pakistan

Email: fatimakhurshid61@yahoo.com

Co-Authors:

Asif Islam

Department of Medicine & Rheumatology

Omar Hospital & Cardiac Centre Lahore, Pakistan

Kinza Shahid Randhawa

Department of Medicine

Ali Fatima Hospital Lahore, Pakistan

Umer Haider

Department of Medicine

Ali Fatima Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan

Memoona Khalood

Department of Radiology

Ali Fatima Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan

Authors Contributions

Asif Islam contributed to the study concept and drafting of the case study. Kinza Shahid Randhawa and Umer Haider were involved in data collection. Fatima Khurshid contributed to manuscript writing and correspondence of all the work, while Memoona Khalood performed the critical review of the manuscript.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None

Guarantor

Fatima Khurshid serves as the guarantor of the work.

DOI

Cite this Article

Khurshid F, Islam A, Randhawa KS, Haider U, Khalood M. Anti-Synthetase Antibody Syndrome: A Case report of Rare and Challenging Diagnosis for Interstitial Lung Disease. medtigo J Emerg Med. 2025;2(4):e3092242. doi:10.63096/medtigo3092242 Crossref