Author Affiliations

Abstract

Background: A mass casualty incident (MCI) presents a significant burden on medical resources, necessitating accurate primary triage to ensure optimal outcomes. Numerous algorithm-based triage systems have been proposed, but their accuracy and reliability remain uncertain. The American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACSCT) recommends an under-triage rate below 5% and an over-triage rate below 50%, but these standards are rarely met.

Aim: This study aimed to assess the replicability of Kilner and Kilner & Hall’s MCI paper exercises, apply 21 identified algorithm-based primary triage systems to the scenario, and statistically compare their accuracy.

Methodology: A quantitative approach was used, analyzing a sample of 30 casualties using analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess differences in performance among triage systems. Modifications were made to ensure compatibility with all systems.

Results: ANOVA results showed no statistically significant difference among systems (P = 0.135). The START/JumpSTART system was most accurate (76.7%), while the Sacco Triage Method was least accurate (40%). None met the <5% under-triage threshold. Modified physiological triage tool-24 (MPTT-24) and national health service major incident triage tool (NHS MITT) showed the best sensitivity/specificity, but still failed ACSCT criteria.

Conclusion: Algorithm-based triage systems do not reliably meet accepted benchmarks. Intuitive triage by experienced paramedics may outperform algorithmic models, warranting further investigation.

Keywords

Triage, Mass casualty incident, Mass casualty triage system, Intuitive primary triage system, Algorithm primary triage systems, Over-triage, Under-triage.

Introduction

In 1983, the Newport Beach Fire Department and the Hoag Memorial Hospital Presbyterian, Los Angeles, California, United States of America (USA), developed a system of sorting casualties based on who needed care first, the simple triage and rapid treatment (START). This algorithm, a primary triage system, was developed to be used by paramedics while responding to an MCI. By the mid-1990s, START had become standard across the USA, later spreading to Canada, Australia, and Europe.[1] START aimed to classify each casualty above 8 years old. Thus, recognising that the normal physiological parameters of children differ from those of adults, in 1995, Lou Romig from the Miami Children’s Hospital developed the JumpSTART Field Pediatric Multicasualty Triage System, hereafter referred to as JumpSTART 1995, to be applied to children between 1 and 8 years of age.[2] In 2002, Lou Roming updated the JumpSTART 1995, becoming JumpSTART Pediatric MCI Triage, hereafter referred to as JumpSTART 2002; and conceived a combination between START and JumpSTART 2002 called Combined START/JumpSTART Triage Algorithm. START also evolved to Modified START, including the presence of radial pulse as an alternative to capillary refill time (CRT).[3]

In the United Kingdom (UK), Kilner developed an MCI paper exercise involving 20 casualties to examine the accuracy of theoretical triage decision-making among physicians, nurses, and paramedics. In his MCI paper exercise and using the SIEVE (Sieve and Sort) Triage, Kilner concluded that paramedics were significantly more likely to over-triage casualties when compared with both physicians and nurses, and there was no significant difference between the professional groups in relation to frequency of under-triage. Kilner paper exercise suggested a predicted triage priority for each casualty but did not provide enough clinical information to classify the casualties correctly, giving space for different interpretations, even when using the SIEVE Triage. Furthermore, when the article was published, the UK paramedics had a relatively reduced number of hours of training.[4]

Later, Kilner & Hall updated the MCI paper exercise from Kilner now involving 20 adults and 10 children. The aim was to determine the accuracy of triage decision-making of firearms-trained police officers with and without printed decision-support materials. Instead of SIEVE Triage, Kilner & Hall applied the modified SIEVE triage and the paediatric triage tape (PTT), also known as smart tape, to be used in casualties below 13 years of age.[5] The predicted triage priority per casualty was not presented in the Kilner & Hall article, but suggested the existence of great potential to provide accurate triage decisions in an MCI with the use of a triage decision support material. However, it is not clear if using MCTS other than the Modified SIEVE Triage and the PTT combined, the results would be the same.

In 2008, the Modified START, the JumpSTART 2002, the Modified SIEVE Triage, the PTT, the Care Flight Triage, the Sacco Triage Method (STM), the Military Triage, Conscienza, Emorragie, Shock, Insufficienza respiratoria, Rotture, Altro (CESIRA), and Homebush were reviewed.[6,7] They suggested the use of the intuitive primary triage system Sort, Assess, Lifesaving interventions, treatment, and/or transport (SALT) as a national guideline for the USA. SALT is currently the MCTS of choice taught by the National Disaster Life Support Foundation (NDLSF) and included in the curricula of most international prehospital courses, such as the American versions of Prehospital Trauma Life Support (PHTLS) and Paediatric Education for Prehospital Professionals (PEPP). However, PHTLS also supports the Modified START and JumpSTART 2002 because these courses recognise that not all paramedics worldwide can gather clinical information, interpret, and evaluate to select an evidence-based choice of action; therefore, to use intuitive primary triage systems.[7]

In 2011, compared the Modified SIEVE Triage in use by the UK Ambulance Service with the military SIEVE triage (MST). With the publication of the national ambulance service medical directors group (NASMeD) triage sieve on behalf of the national ambulance resilience unit (NARU), the UK ambulance service moved away from the modified SIEVE triage and implemented NASMeD triage sieve into their practice.[8] In 2017, the modified physiological triage tool (MPTT) was published, and the MPTT-24 months later. In 2022, the national health service published the major incident triage tool (NHS MITT), and the ten-second triage (TST) months later. Both NHS MITT and TST are expected to be implemented into practice soon.[9,10]

Intuitive Vs Algorithm primary triage systems: Although clinical theory is paramount for paramedic training, the paramedics typically learn by pattern recognition, associating the presentation of the casualty with a specific clinical diagnosis and, consequently, with a specific clinical outcome. Thus, the accuracy of intuitive primary triage systems may depend on the experience and knowledge of the paramedics, creating a risk of misinterpretations and, consequently, inaccurate results. Examples are the expressions “Not in respiratory distress?” or “Likely to survive given current resources?” from the SALT triage system, or the identification of “Shock” and “Respiratory insufficiency” from CESIRA.[11] So, while triaging casualties using an intuitive primary triage system, the accuracy of the triage executed by a Portuguese Tripulante de Ambulância de Socorro with only 210 hours of training should be different in comparison to the accuracy of the triage executed by a UK paramedic with a minimum of three-year bachelor of science (BSc) degree in Paramedic Science, using critical thinking and evidence-based practice.[12] Algorithm primary triage systems were conceived to be followed with no deviation, being simple, rapid, and easy to apply, therefore more appropriate to the Portuguese emergency medical service (EMS).

Secondary triage: Furthermore, some authors claim that primary triage systems are not perfect, suggesting the application of secondary triage on the scene. The primary triage on the scene is considered a quick overview, spending only seconds for each casualty to identify immediate threats. The secondary triage on scene involves an examination and evaluation of the condition of the casualty. Examples of the use of the modified START, followed by the secondary assessment of victim endpoint (SAVE) in the USA, or the modified SIEVE triage, followed by SORT in the UK.[13] It is important to highlight that, presently, in some countries, triage is normally divided into three phases: primary triage, performed by the EMS dispatch centre; secondary triage, performed by the first paramedic on the scene; and third triage, upon arrival at the ED. Including each extra triaging moment will inevitably increase the time spent, delaying the delivery of treatment and transport. According to Castle, performing a secondary triage on the scene has the potential to under-triage the casualty who, despite being critical, has acceptable vital signs secondary to compensatory mechanisms.[14] The triage system is a standardised method of rapidly determining the clinical urgency of the casualties and prioritising them; therefore, it is part of an assessment and not a treatment.

Aim: This study aims to statistically examine Kilner (2002) and Kilner & Hall (2004 )’s MCI paper exercises previously published and their replicability; apply all the identified MCTS to the MCI paper exercise; and statistically compare the accuracy of its results.

Methodology

The study adopted an objectivist, positivist, and quantitative approach. Descriptive statistical analysis was applied to a non-random secondary sample (n) of 30 casualties presented by Kilner (2002) and Kilner & Hall (2004), as an MCI paper exercise.[3,5] This study only applies algorithm primary triage systems, a triage system that can be quickly applied by any paramedic to casualties on the scene without the use of any diagnostic equipment. Some modifications were made, and additional information was added to make it possible to apply all the identified algorithm primary triage systems.

Ethics: Privacy, confidentiality, and consent are factors to be considered while analysing non-random secondary n. Kilner (2002) and Kilner & Hall (2004) did not disclose any information regarding n capable of identifying the casualties. Nevertheless, the Kilner (2002) and Kilner & Hall (2004) MCI paper exercises were understood to be fictitious. Regarding ethics of triage, MCTS rely, implicitly or explicitly, on paramedic values such as beneficence, autonomy, non-maleficence, and justice. Nevertheless, when used, MCTS also should comply with the three principles of distributive justice: the principle of utility, the difference principle, and the principle of equal chances. If the word triage means to pick out or sort, and its application aims to achieve the greatest good for the greatest number of casualties using the minimal amount of time due to potential resource limitations, triage can be considered a discriminatory process.[15] The use of MCTS raises ethical questions when the delivery of care is denied, and to be lawful in the UK (except Northern Ireland), the MCTS needs to comply with the Equality Act 2010 and its nine protected characteristics.

12 Variable factors: In their MCI paper exercises, Kilner (2002) and Kilner & Hall (2004) provided information about the number of casualties, their sex, age, and height for paediatric casualties. However, the MCI paper exercises do not provide enough clinical information necessary to apply all the identified algorithms in the primary triage systems. Due to such reason, some information was added or adapted taking into consideration 12 variable factors: the scene description; the age of the casualty; the height of the casualty if paediatric; catastrophic bleeding; their ability to walk; their Alert, Verbal, Painful, Unresponsiveness (AVPU) scale; their Glasgow Coma Score (GCS); their Respiratory Rate (RR) per minute; their Heart Rate (HR) per minute; the patency of their airway; the presence or absence of radial pulses; and their CRT.

Data analysis: A triage table error (TET) was developed, inspired by the table error from Dittmar et al., with the introduction of a numeric classification.[16]

| Expected triage category | |||||

| Triaged As | Priority 1 | Priority 2 | Priority 3 | Priority 0 | |

| Priority 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Priority 2 | -2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Priority 3 | -3 | -2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Priority 0 | -4 | -4 | -4 | 0 | |

Table 1: TET

Based on the classification from Kilner (2002), the 30 casualties were classified as Priority 1 (P1), Priority 2 (P2), Priority 3 (P3), and Priority 0 (P0). When an algorithm primary triage system classifies the casualty according to the expected triage category, the TET classification is “0”. However, when an algorithm primary triage system classifies a casualty one priority below their expected triage category, the TET classification is “-2” due to the consequences that under-triage has in the outcome of the casualty. When the casualty is salvageable and an algorithm primary triage system classifies the casualty as P0, the TET classification is “-4” because, once classified as P0, the casualty probably will not receive any care afterward.

Priority 4 (P4) was not included in this study because such a decision requires clinical judgment and, therefore, is intuitive. The use of this classification suggests that paramedics must have robust clinical knowledge, and algorithm-based primary triage systems should not be used. P4 is defined as “casualties that are so severe that they cannot survive despite the best available care and whose treatment would divert medical resources from salvageable casualties who may then be compromised.” An Accuracy Chart was produced with the number of correct and incorrect triage classifications, and Microsoft Excel was used to analyse the data. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) Single Factor was applied to the triage results, aiming to find the P-value with an α of 0.01; F value; and F crit.

Under-triage and Over-triage: During the process of triaging a casualty, errors can be committed. It is considered over-triage when a casualty is classified in a more severe triage category than what they should be identified with. On the other hand, it is considered under-triage when a casualty is classified in a less severe triage category than what they should be identified.[17] ACSCT recommends an under-triage rate under 5% and an over-triage rate under 50%. However, this recommendation is far from optimal. Although over-triaging can be accepted in most developed countries with abundant resources to avoid under-triage, it will cause economic, logistical, financial, and administrative pressure on the EMS, and, consequently, the emergency departments (ED), Trauma Units, and Trauma Centers will be receiving many more casualties than are feasible for them to treat. This will significantly delay the definitive care of the casualties, leading to unnecessary mortality among the more salvageable casualties. For such reason, it is essential to distinguish casualties who have life-threatening injuries from those who have non-severe injuries.[18] Although the accepted percentage of under-triage is relatively low, if a casualty falls into that category, the consequences will be catastrophic.

Another problem is how to deal with the cost of treatment, pushing the limited resources of the hospitals onto those casualties who do not immediately need it. A study from 2013 performed in seven regions of the USA estimated that the average adjusted per-episode cost of care was $5,590 higher in a trauma center than in a trauma unit or an ED. The study also concluded that of the 248,342 identified low-risk casualties that did not meet prehospital triage guidelines for transport to a trauma center, 85,155 were still transported to trauma centers. According to this study, improving prehospital triage guidelines that minimize the over-triage of low-risk injured casualties to trauma centers could save up to $136.7 million annually in the seven regions.[19]

Results

A total of 68,259 articles were analysed. Duplicated files and articles related to triage systems referring to specific pathologies, such as cerebrovascular accidents or myocardial infarcts, were excluded. A total of 163 triage systems were identified. Of those, 59 were identified as secondary triage systems, taking into consideration their requirement to measure the blood pressure (BP) and/or saturation of peripheral oxygen (SpO2) and/or Saturation of peripheral carboxyhemoglobin (SpCO).[20] 57 triage systems were identified as hospital triage systems, taking into consideration their requirements to measure variables not available in the prehospital setting. 58 triage systems were identified as primary triage systems: 21 algorithmic, 13 specific for burns, 10 specific for chemical, biological, radioactive, and nuclear (CBRN), 19 specific for paediatric, and three specific for mental health. Some triage systems were identified in more than one category.

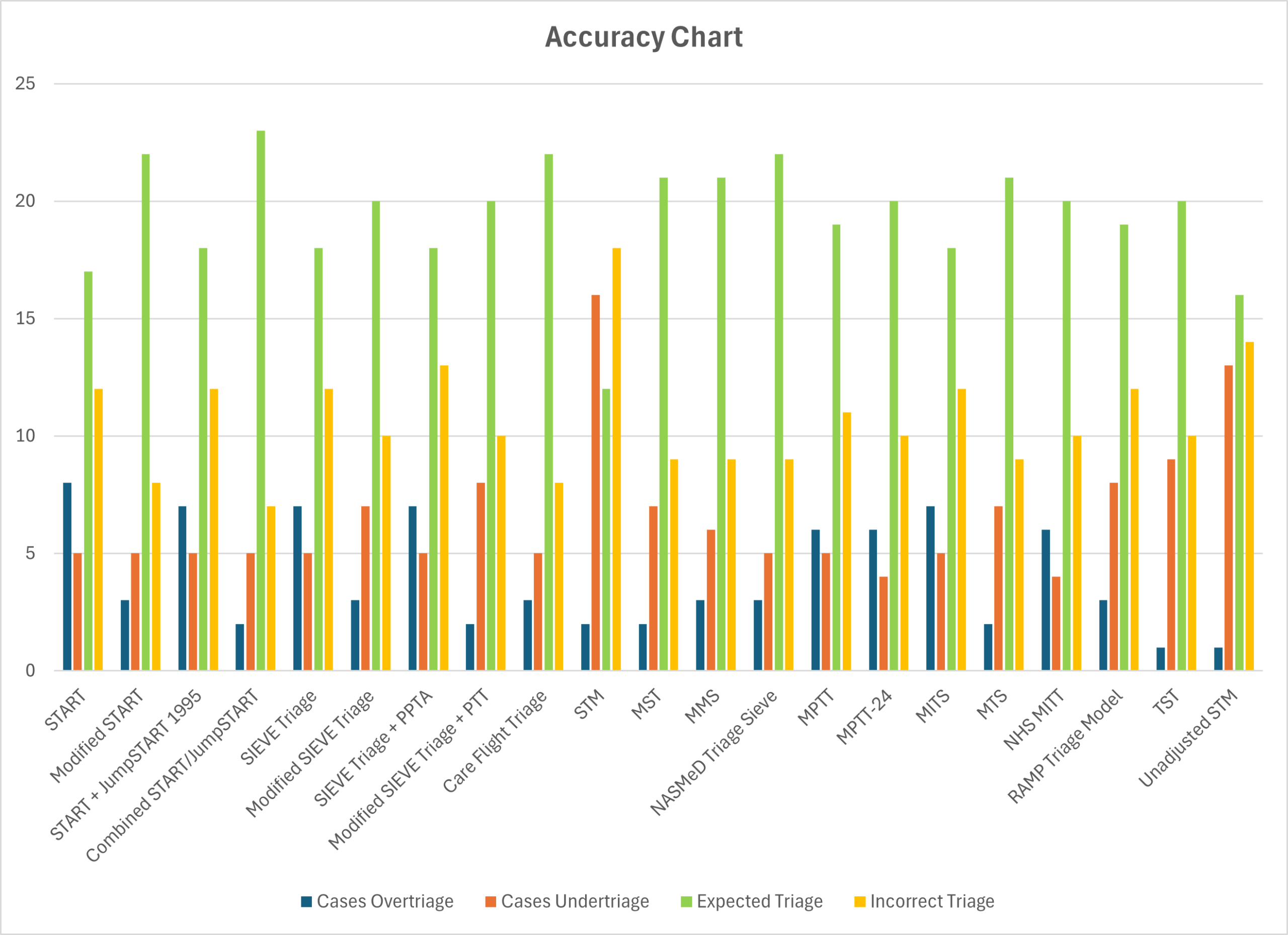

Accuracy chart: Using the TET and based on the triage results, the accuracy chart was produced:

Figure 1: Accuracy chart

Observing the accuracy chart, the combined START/JumpSTART triage algorithm appears to be the most accurate algorithm, primary triage system with 23 (76.7%) correct results, 2 (6.7%) over-triage, and 5 (16.7%) under-triage rate. Nevertheless, the combined START/JumpSTART triage algorithm failed to comply with a maximum of 5% under-triage rate suggested by ACSCT. STM appears to be the least accurate algorithm, primary triage system with 12 (40%) correct results, 2 (6.7%) over-triage, and 16 (53.3%) under-triage rate, failing to comply with a maximum of 5% under-triage rate suggested by ACSCT. TST and Unadjusted STM appear to be the most accurate in over-triage rate, with 1 (3.3%). Nevertheless, both failed to comply with a maximum of 5% under-triage rate suggested by ACSCT, with 9 (30%) and 13 (43.3%) rates, respectively.[21]

START appears to be the least accurate in over-triage rate, with 8 (26.7%), complying with the maximum of 50% over-triage rate suggested by ACSCT. MPTT-24 and NHS MITT appear to be the most accurate in under-triage rate, with 4 (13.3%), but not complying with a maximum of 5% under-triage rate suggested by ACSCT. STM also appears to be the least accurate in under-triage rate, with 16 (53.3%), not complying with a maximum of 5% under-triage rate suggested by ACSCT. Although the accepted percentage of under-triage is only 5%, when it happens, the consequences may be catastrophic for the casualty. In this MCI paper exercise, all 21 algorithm primary triage systems failed to achieve an under-triage rate below 5%. Therefore, they should not be considered suitable to continue to be used as MCTS.[22]

Statistics: ANOVA single factor shows a P-value result of 0.135 (above 0.01), suggesting that there is no statistical difference between the triage results. F of 1.35 and F crit of 1.90 (F < F crit) also suggest the test is not significant (Tables 2 and 3).

| Groups | n | Ʃ | x̅ | S² |

| START | 30 | 49 | 1.633 | 1.206 |

| Modified START | 30 | 54 | 1.800 | 1.131 |

| START + JumpSTART 1995 | 30 | 50 | 1.667 | 1.195 |

| Combined START/JumpSTART | 30 | 55 | 1.833 | 1.109 |

| SIEVE triage | 30 | 49 | 1.633 | 1.206 |

| Modified SIEVE triage | 30 | 56 | 1.867 | 1.085 |

| SIEVE triage + PPTA | 30 | 49 | 1.633 | 1.206 |

| Modified SIEVE triage + PPT | 30 | 58 | 1.933 | 1.030 |

| Care flight triage | 30 | 55 | 1.833 | 1.109 |

| Sacco triage method | 30 | 74 | 2.467 | 0.740 |

| MST | 30 | 57 | 1.900 | 1.059 |

| MMS | 30 | 55 | 1.833 | 1.109 |

| NASMeD triage sieve | 30 | 53 | 1.767 | 1.082 |

| MPTT | 30 | 51 | 1.700 | 1.183 |

| MPTT-24 | 30 | 49 | 1.633 | 1.137 |

| MITS | 30 | 49 | 1.633 | 1.206 |

| MTS | 30 | 57 | 1.900 | 1.059 |

| NHS MITT | 30 | 49 | 1.633 | 1.137 |

| RAMP triage model | 30 | 51 | 1.700 | 1.459 |

| TST | 30 | 60 | 2.000 | 0.966 |

| Unadjusted STM | 30 | 70 | 2.333 | 0.920 |

Table 2: ANOVA single factor – summary

| Source of variation | SS | df | MS | F | P-value | F crit |

| Between groups | 30.194 | 20 | 1.510 | 1.359 | 0.135874 | 1.908602 |

| Within groups | 676.600 | 609 | 1.111 | |||

| Total | 706.794 | 629 |

Table 3: ANOVA single factor of triage results

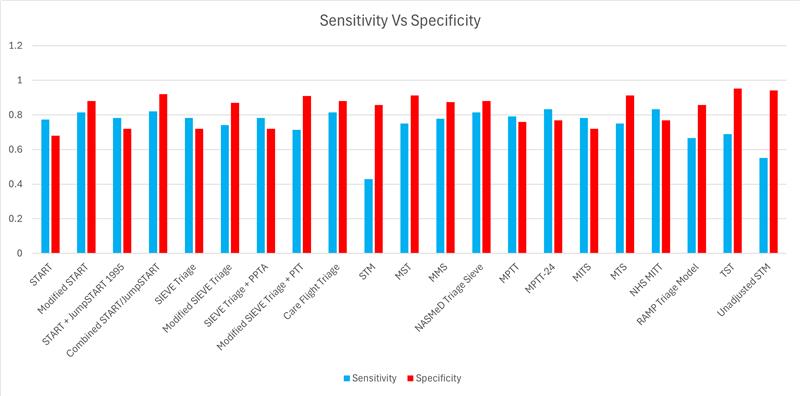

Sensitivity and specificity: The sensitivity and specificity of the 21 algorithm primary triage systems were calculated:

Figure 2: Sensitivity & specificity

MPTT-24 and NHS MITT have both a maximum sensitivity of 83.33%, with a specificity of 76.92%. STM has a minimum sensitivity of 42.86%, with a specificity of 85.71%. TST has a maximum specificity of 95.24%, with a sensitivity of 68.97%. START has a minimum specificity of 68.00%, with a sensitivity of 77.27%. According to Power et al, the rule of thumb for an acceptable sensitivity and specificity is above 80%. Applying the rule to this MCI paper exercise, only the Modified START, the Combined START/JumpSTART Triage Algorithm, Care Flight Triage, and NASMeD Triage SIEVE could be considered acceptable to be used.[23] Nevertheless, other authors have different conclusions. Malik et al concluded that Modified START has a sensitivity of 57.20% and a specificity of 89.00%, therefore failing the Power et al rule. Although Garner et al concluded that care flight triage has a sensitivity of 82.00%, Vassallo et al, Horne et al, Challen et al, and Malik et al attribute care flight triage a sensitivity of 33.5%, 45.00%, 50.00%, and 43.30% respectively, therefore failing the Power et al rule. Malik et al also attribute a sensitivity of 44.90% to NASMeD triage SIEVE, failing the Power et al minimum acceptable sensitivity and specificity of 80%.[24]

Discussion

For this study, the paediatric primary triage algorithm (PPTA) was used in conjunction with SIEVE triage. The Modified Military SIEVE (MMS), major incident triage SIEVE (MITS), military triage SIEVE (MTS), and rapid assessment of mentation and pulse (RAMP) triage model were also identified as algorithm primary triage systems and used in this study.[25] JumpSTART 2002 was initially identified as an algorithmic primary triage system capable of being combined with Modified START. Nevertheless, with the combined START/JumpSTART triage algorithm identified, JumpSTART 2002 alone was not considered for this study.

The pediatric South African triage score was also identified as an algorithmic primary triage system. Nevertheless, such a system was published in combination with the South African triage scale or with the Cape triage score. Taking into consideration that the South African triage scale and/or Cape triage score require the measurement of BP, therefore unacceptable to be considered a primary triage system due to the time spent, the pediatric South African triage score was not considered for this study.[26] STM and Unadjusted STM are numerical triage systems. These triage systems use a computer-based system that requires paramedics to use a scorecard, laptop, or tablet to calculate the score of the casualty; therefore, their priority. Nevertheless, because it is possible to use these two triage systems without such equipment, STM and unadjusted STM were considered for this study.

Homebush triage taxonomy, reviewed by Lerner et al, was considered a colour code system to be applied in conjunction with other MCTS such as START. Therefore, it was not considered an MCTS and was not considered for this study.[27] Lerner et al suggest the use of SALT, an intuitive primary triage system, as a national guideline for the USA.[6] SALT has the potential to be superior to algorithm primary triage systems if used by experienced paramedics. Studying the accuracy of intuitive primary triage systems and algorithm primary triage systems is difficult, taking into consideration multiple variables and factors. Therefore, further research is needed.[28] Simulation of MCIs is an alternative to measure the accuracy of the intuitive primary triage systems and algorithmic primary triage systems. Such simulations can be difficult to recreate due to the absence of stress from the paramedics. Without stress, the simulation will produce controversial results.[29]

The failure of algorithm primary triage systems may be attributed to the complex decision-making process that needs to fit into a concrete and objective set of guidelines. Individuals performing triage have the ability and responsibility to make lifesaving decisions within seconds based on limited information.[30] If much of triage is done on emotional or other subjective grounds, personal interpretation rather than adherence to the objective criteria may likely become the guiding impulse and thus, the source of error and failure of proper allocation of resources.[31]

Equality Act 2010

In the civilian world, paramedics may come across casualties who take medication such as beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers, preventing them from having an increase in HR, therefore affecting the triage classification. A similar situation occurs when a casualty has a definitive pacemaker due to a complete atrioventricular block.[32] The disability of some casualties and the medication they take can positively or negatively influence their vital signs, with consequences for their triage classification. Its opposite is also true. An athlete at rest can reach an HR from 24 to 48.[33] All algorithm primary triage systems failed to correctly address the protected characteristics “disability” and/or “age”. Such characteristics are expected to be detected by an experienced paramedic while assessing a casualty, but not by less experienced or trained EMS providers.

Recommendations

Given these findings, algorithmic primary triage systems are not recommended for use during MCIs. Instead, intuitive primary triage systems—when applied by experienced paramedics—may offer superior performance. Further research is essential to validate this potential and to develop triage systems that meet both ACSCT standards and legal frameworks such as the Equality Act 2010.

Conclusion

CI imposes significant demand on medical resources, necessitating an efficient MCTS to ensure optimal casualty outcomes. This study evaluated 21 algorithm-based primary triage systems. The Combined START/JumpSTART Triage Algorithm showed the highest overall accuracy, while the Sacco triage method (STM) demonstrated the lowest. Despite varying performance, none of the algorithms met the ACSCT standard of under 5% under-triage. ANOVA analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between the systems.

MPTT-24 and NHS MITT displayed the highest sensitivity (83.33%) and specificity (76.92%), while STM had the lowest sensitivity (42.86%). TST had the highest specificity (95.24%). START had the lowest specificity (68%). All 21 triage systems failed to meet the under-triage benchmark and failed to comply with the Equality Act 2010.

References

- Hart A, Nammour E, Mangolds V, Broach J. Intuitive versus algorithmic triage. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2018;33(4):355-361. doi:10.1017/S1049023X18000626 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Jerkins J, McCarthy M, Sauer L, et al. Mass-casualty triage: time for an evidence-based approach. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2008;23(1):3-8. doi:10.1017/s1049023x00005471 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kilner T. Triage decisions of prehospital emergency health care providers, using a multiple casualty scenario paper exercise. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:348-353. doi:10.1136/emj.19.4.348 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Advanced Life Support Group. Major Incident Medical Management and Support: The Practical Approach. BMJ publishing group; 1995. Major Incident Medical Management and Support: The Practical Approach

- Kilner T, Hall E. Triage decisions of United Kingdom police firearms officers using a multiple-casualty scenario paper exercise. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2004;20(1):40-46. doi:10.1017/s1049023x00002132 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lerner E, Schwartz R, Coule P, et al. Mass casualty triage: an evaluation of the data and development of a proposed national guideline. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2008;2(1):S25-34. doi:10.1097/DMP.0b013e318182194e PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Tiffen J, Corbridge S, Slimmer L. Enhancing clinical decision making: development of a contiguous definition and conceptual framework. J Prof Nurs. 2014;30(5):399-405. doi:10.1016/j.profnurs.2014.01.006 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Horne S, Vassallo J, Read J, Ball S. UK triage – an improved tool for an evolving threat. Injury. 2011;44(1):23-28. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2011.10.005 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Vassallo J, Beavis J, Smith J, Wallis L. Major incident triage: derivation and comparative analysis of the Modified Physiological Triage Tool (MPTT). Injury. 2017;48(1):992-999. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2017.01.038 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Vassallo J, Moran C, Cowburn P, Smith J. New NHS prehospital major incident triage tool: from MIMMS to MITT. Emerg Med J. 2022;0:800-802. doi:10.1136/emermed-2022-212569 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Stephenson J, Andrews L, Moore F. Developing and introducing a new triage sieve for UK civilian practice. Trauma. 2014;17(2):140-141. doi.org/10.1177/1460408614561173 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wilson A, Howitt S, Holloway A, Williams AM, Higgins D. Factors affecting paramedicine students’ learning about evidence-based practice: a phenomenographic study. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):45. doi:10.1186/s12909-021-02490-5 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Benson M, Koenig K, Schultz C. Disaster triage: START, then SAVE – a new method of dynamic triage for victims of a catastrophic earthquake. Prehosp Disaster Med. 1996;11(2):117-124. doi:10.1017/s1049023x0004276x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bazyar J, Farrokhi M, Khankeh H. Triage systems in mass casualty incidents and disasters: a review study with a worldwide approach. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7(3):482-494. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2019.119 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Australasian College for Emergency Medicine. Guidelines on the Implementation of the Australasian Triage Scale in Emergency Departments. 2023. Guidelines on the Implementation of the Australasian Triage Scale in Emergency Departments

- Dittmar M, Wolf P, Bigalke M, Graf B, Birkholz T. Primary mass casualty incident triage: evidence for the benefit of yearly brief re-training from a simulation study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2018;26:35. doi:10.1186/s13049-018-0501-6 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Burkle F, Sanner P, Wolcott B. Disaster Medicine: Application for the Immediate Management and Triage of Civilian and Military Disaster Victims. Medical Examination Publishing Co., Inc.; 1984. Disaster Medicine: Application for the Immediate Management and Triage of Civilian and Military Disaster Victims

- Gaul A. Mass casualty triage: an in-depth analysis of various systems and their implications for future considerations. Master’s thesis. University of Pittsburgh; 2015. Mass casualty triage: an in-depth analysis of various systems and their implications for future considerations

- Nguyen H, Meczner A, Burslam-Dawe H, Hayhoe B. Triage errors in primary and pre-primary care. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(6):e37209. doi:10.2196/37209. PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Williams C, Clemency J, Lazada M, Sanddal N, eds. Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patients. American College of Surgeons; 2014. Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patients

- Frykberg E. Triage: principles and practice. Scand J Surg. 2005;94:272-278. doi:10.1177/145749690509400405 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Voskens F, Rein E, Sluijs R, et al. Accuracy of prehospital triage in selecting severely injured trauma patients. JAMA. 2017;153(4):1. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4472 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Newgard C, Staudenmayer K, Hsia R, et al. The cost of overtriage: more than one-third of low-risk injured patients were taken to major trauma centers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(9):1591-1599. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1142 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Malik N, Chernbumroong S, Xu Y, et al. The BCD Triage Sieve outperforms all existing major incident triage tools: comparative analysis using the UK national trauma registry population. eClinicalMedicine. 2021;36:100888. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100888 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Power M, Fell G, Wright M. Principles for high-quality, high-value testing. Evid Based Med. 2012;18(1):5-10. doi:10.1136/eb-2012-100645 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cross K, Cicero M. Head-to-head comparison of disaster triage methods in pediatric, adult, and geriatric patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.12.023 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mackway-Jones K, Carley S, Robson J. Planning for major incidents involving children by implementing a Delphi study. Arch Dis Child. 1999;80:410-413. doi:10.1136/adc.80.5.410 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Falzone E, Pasquier P, Hoffmann C, et al. Triage in military settings. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2016;36:43-51. doi:10.1016/j.accpm.2016.05.004 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cheema B, Westwood A. Paediatric triage in South Africa. South Afr J Child Health. 2019;7(2):43-45. doi:10.7196/sajch.585 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Twomey M, Wallis LA, Thompson ML, Myers JE. The South African Triage Scale (adult version) provides reliable acuity ratings. Int Emerg Nurs. 2012;20(3):142-150. doi:10.1016/j.ienj.2011.08.002 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wallis L, Gottschalk S, Wood D, Bruijns S, Vries S, Balfour C. The Cape Triage Score a triage system for South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2006;96(1):53-56. The Cape Triage Score a triage system for South Africa

- Atzema C, Austin P. Rate control with beta-blockers versus calcium channel blockers in the emergency setting: predictors of medication class choice and associated hospitalization. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(11):1334-1348. doi:10.1111/acem.13303 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Knabben V, Chhabra L, Slane M. Third-degree atrioventricular block. eBook. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Third-degree atrioventricular block

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Csaba Dioszeghy from the College of Remote and Offshore Medicine.

Funding

No funding bodies/grants supported this research or contributed to the author’s salary.

Author Information

Alfredo Manuel da Silva Leal

Independent Researcher

College of Remote and Offshore Medicine, Portugal

Email: a.leal@corom.edu.mt

Author Contribution

The author contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles and was involved in the writing – original draft preparation and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest Statement

I, Alfredo Manuel da Silva Leal, declare that I have no conflict of interest relating to this article. I have no personal, financial, or other relationships that could influence my work or decisions in this matter.

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Leal AMS. Algorithm Primary Triage Systems Should Not Be Used in Mass Casualty Incidents. medtigo J Emerg Med. 2025;2(3):e3092233. doi:10.63096/medtigo3092233 Crossref