Author Affiliations

Abstract

Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) is a rare and progressive mitochondrial disorder most caused by the m.3243A>G point mutation. The disease affects multiple organ systems, including the central nervous system, muscular system, and cardiovascular system, and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality across a wide age range. Here, we present the case of a 44-year-old male with genetically confirmed MELAS who developed cardiogenic shock, multiorgan failure, and metabolic decompensation. Despite aggressive standard mitochondrial support therapy (MST), his clinical condition continued to deteriorate, ultimately resulting in death. This manuscript explores the underlying mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction in MELAS, with a focus on its cardiovascular complications, particularly cardiogenic shock. We further review the limitations of existing treatment options and examine the potential therapeutic role of emerging interventions such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP) supplementation, EPI-743 (vatiquinone), and intravenous nicotinamide. Our goal is to highlight the urgent need for novel and more effective interventions in this vulnerable patient population.

Keywords

Mitochondria, Stroke, Adenosine triphosphate, Maternal inheritance, Metabolic crisis.

Introduction

Mitochondrial diseases represent the most common form of inherited neurometabolic disorders, arising from mutations in either nuclear deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) or mitochondrial genomes (mtDNA). These conditions exhibit remarkable heterogeneity in both clinical presentation and genetic etiology, creating substantial challenges for diagnosis, clinical management, and understanding of underlying molecular mechanisms.[1] Among these disorders, MELAS stands as one of the most prevalent maternally inherited mitochondrial diseases, with profound impacts on the nervous system and skeletal muscles.[2] MELAS typically emerges in childhood or early adulthood following a period of apparently normal development. The syndrome is characterized by distinctive hallmark features, including recurrent stroke-like episodes, seizures, migraine-like headaches, episodic vomiting, progressive muscle weakness, and lactic acidosis. The disease typically follows a relapsing-remitting course that leads to cumulative neurological damage, resulting in progressive cognitive deterioration and eventual dementia.[2] Unlike conventional ischemic strokes, the stroke-like episodes in MELAS have a metabolic rather than vascular etiology, stemming from fundamental mitochondrial dysfunction rather than vascular occlusion. This distinctive pathophysiology leads to cortical necrosis and irreversible neurological deficits, characterized by a unique clinical profile. Beyond its neurological manifestations, MELAS presents as a multi-system disorder with wide-ranging clinical features that may include dementia, epilepsy, myopathy, recurrent headaches, sensorineural hearing impairment, diabetes mellitus, and growth abnormalities manifesting as short stature.[2]

From a genetic perspective, MELAS is predominantly associated with specific mitochondrial DNA mutations. Approximately 80% of affected patients carry the m.3243A>G mutation in the MT-TL1 gene encoding mitochondrial tRNALeu (UUR), while roughly 7-15% harbor the m.3271T>C variant.[3] The complex maternal inheritance pattern and variable tissue heteroplasmy levels contribute significantly to the phenotypic diversity observed across patients. Diseases caused by m.3243A>G are one of the most phenotypically diverse of all mitochondrial diseases [2]. MELAS is primarily caused by pathogenic mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), with the most common being “m.3243A>G” in the “MT-TL1” gene, which encodes mitochondrial transfer RNA for leucine tRNA^Leu (UUR).[4] This mutation disrupts mitochondrial protein synthesis, impairing oxidative phosphorylation and resulting in reduced ATP production, particularly in high-energy-demand tissues such as the brain, muscles, and heart.[5] Due to the unique maternal inheritance pattern of mtDNA, disease severity and presentation vary widely depending on the proportion of mutated mitochondria (heteroplasmy) in different tissues.

Higher heteroplasmy levels correlate with earlier disease onset and more severe manifestations, while lower levels may result in milder phenotypes or asymptomatic carriers. Mutation also plays a role in metabolic dysfunction, contributing to the hallmark “lactic acidosis” seen in MELAS patients. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of this mutation has provided valuable insights into disease pathogenesis and potential therapeutic strategies targeting mitochondrial metabolism. This paper aims to explore the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying MELAS syndrome and discuss novel therapeutic strategies that may offer improved clinical outcomes for affected individuals.

Case Presentation

We report a 44-year-old male with a documented diagnosis of MELAS due to the m.3243A>G mutation in the MT-TL1 gene. His longstanding clinical history was notable for childhood-onset sensorineural hearing loss, epilepsy, insulin-resistant diabetes mellitus, short stature, progressive cardiomyopathy, and recurrent stroke-like episodes necessitating multiple hospital admissions. These manifestations were consistent with a high burden of mitochondrial dysfunction affecting multiple organ systems. He presented to the emergency department following a three-day history of sore throat, cough, nausea, vomiting, and poor oral intake. His parents, who accompanied him, reported a possible environmental toxin exposure due to a recent gas leak in their home. On arrival, he was hypothermic and hypotensive, prompting urgent evaluation and escalation of care. He was not taking prescribed outpatient medication and reportedly self-administered antibiotics obtained abroad. Initial laboratory findings were notable for severe metabolic acidosis (pH 7.1, bicarbonate 6 mmol/L, anion gap 28), acute kidney injury (Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 113 mg/dL, Creatinine (Cr) 7.61 mg/dL), transaminitis (Aspartate transaminase (AST) >1100 IU/L, alanine transaminase (ALT) >1200 IU/L), hyperlactatemia (lactate 8.2 mmol/L), hyponatremia (Na 128 mmol/L), and leukocytosis (White blood cells (WBC) 16K/uL) shown in Table 1.

| Laboratory parameter | Value |

| pH | 7.1 |

| Bicarbonate | 6 mmol/L |

| Anion Gap | 28 |

| BUN | 113 mg/dL |

| Cr | 7.61 mg/dL |

| AST | >1100 IU/L |

| ALT | >1200 IU/L |

| Lactate | 8.2 mmol/L |

| Sodium (Na) | 128 mmol/L |

| WBC | 16,000 /µL |

Table 1: The initial laboratory findings seen in the patient

Case Management

Imaging included a non-contrast head computed tomography (CT) that demonstrated a left posterior parietal infarct of indeterminate age, without signs of acute ischemia or hemorrhage. Echocardiography revealed a severely reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (25–30%) with severe global hypokinesis, moderate right ventricular dilation with systolic dysfunction, and moderate mitral and tricuspid regurgitation. These findings were consistent with decompensated cardiogenic shock in the setting of mitochondrial cardiomyopathy. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) and intubated for encephalopathy and respiratory failure. He initiated continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) for anuric renal failure and volume overload.

Nutritional support started with high-concentration dextrose (D10%), SMOF lipids, and insulin infusion to prevent catabolism and provide metabolic substrate. However, severe hypertriglyceridemia (>2,600 mg/dL) necessitated discontinuation of lipids, and the dextrose concentration was increased to D20%. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) was subsequently initiated with stable glucose levels. MST was initiated, including IV L-arginine for neuroprotection, coenzyme Q10 to enhance electron transport, levocarnitine to support fatty acid metabolism, and citrulline. The labs that were trended while optimizing the MST, as well as monitoring the success of CRRT, are shown in Table 2. It is to be noted that the patient was admitted to the ICU for a long time, so it was difficult to list every single lab value measure for the patient. Thus, lab values from the end of the week are averaged and shown in Table 2.

| Lab value | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 |

| Na+/K+/Cl– * | 131/5.6/98 | 133/4.7/107 | 133/4.5/100 | 131/4.1/104 |

| BUN* | 114 à 70 | 50 | 30 | 27 |

| Cr* | 6.97 à 3.57 | 1.64 à146 | 0.52 à 1.82 | 1.39 |

| ABG* pH/PCO2/HCO3– |

7.26/35/15 | 7.37/38/21 | 7.29/40.6/19.7 | 7.29/37.6/18 |

| Lactate* | 9.0 à7.2 | 3.1 à 2.3 | 1.3 | 6.7 à7.3 |

| WBC* | 16.4 à11.5 | 12.0 | 29.6 | 38.2 à 18.2 |

| Hb* | 9.1 à10.5 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 6.8 à 8.3 |

| Glucose* | 206 à110 | 163 | 130 | 152 |

| ALT/AST | 1597/1200 | Not measured | 56/52 | 358/218 |

| Triglycerides | 2284 | Not measured | Not measured | Not measured |

Table 2: Lab values over the 4 weeks of admission. * Shows lab values that are an average throughout the week

Due to the mitochondrial toxicity associated with propofol, the sedative was discontinued shortly after admission. Despite these comprehensive interventions, the patient’s condition continued to deteriorate. Clinically, he remained encephalopathic, sedated, and hemodynamically unstable, requiring vasopressor support. Serial laboratory testing revealed worsening hepatic and renal function, and neurologic assessments remained limited due to sedation and ventilation. The constellation of multiorgan failure, refractory cardiogenic shock, and ongoing catabolic stress reflected profound mitochondrial energy failure. Despite the use of standard mitochondrial therapies, metabolic stabilization could not be achieved, emphasizing the critical need for novel interventions aimed at directly restoring cellular ATP in MELAS crises.

Figure 1: CT scan of a 44-year-old MELAS patient showing infraction and ischemic changes

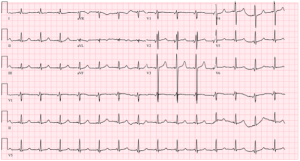

Figure 2: ECG finding of a 44-year-old MELAS patient who had progressive cardiomyopathy since childhood

Discussion

The mitochondrial genome consists of 37 genes encoded within a 16,569 bp double-stranded circular mtDNA molecule. The unique genetic properties of mitochondria, particularly maternal inheritance and heteroplasmy, contribute significantly to the diverse clinical manifestations observed in mitochondrial diseases. Heteroplasmy, the coexistence of mutated and wild-type mtDNA within cells, creates a threshold effect for clinical expression that varies between different tissues based on their energy demands and mitochondrial content. Among the most clinically significant mtDNA mutations are m.1555A>G (associated with aminoglycoside-induced deafness), m.3460G>A and m.11778A>G (associated with Leber’s Hereditary Optic Neuropathy), and notably, the m.3243A>G mutation in mitochondrial tRNA-Leu (UUR) that predominantly underlies both MELAS syndrome and Maternally Inherited Diabetes and Deafness (MIDD).[6]

The m.3243A>G mutation represents the genetic basis for approximately 80% of MELAS cases, making it the most common causative mutation for this syndrome. The wide variability in clinical manifestations of MELAS remains incompletely understood, though heteroplasmy significantly contributes to this phenotypic diversity. Approximately one-third of patients develop cardiac disease, which frequently contributes to increased mortality. This cardiac involvement exemplifies the threshold effect, where tissues are affected to varying degrees based on their energetic demands and mutational load, resulting in cardiomyopathy in some patients while being absent in others. Multiple studies have demonstrated that higher heteroplasmy levels correlate with more severe clinical manifestations, including seizures, stroke-like episodes, and myopathy, and typically predict an earlier age of disease onset. Conversely, lower heteroplasmy levels more commonly manifest as hearing loss, visual impairment, and gastrointestinal dysfunction.[7]

Current therapeutic approaches like MST represent the current standard of care for MELAS and aim to optimize mitochondrial function through a combination of preventive measures, metabolic stabilization, and avoidance of mitochondrial toxins. The case presented herein underscores the critical need for more effective mitochondrial-directed therapies, particularly during acute metabolic decompensation. Contemporary MST primarily employs supplementation with several key compounds: Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10). This essential electron carrier in the mitochondrial respiratory chain plays a crucial role in oxidative phosphorylation and ATP production.[8]

Riboflavin: As a precursor for flavoproteins vital to electron transport and energy metabolism, riboflavin has demonstrated efficacy in slowing disease progression in multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiencies.[8] Creatine: Acting as a high-energy phosphate shuttle between mitochondria and cytoplasmic sites of ATP utilization, creatine supplementation has been shown to improve muscle function in patients with mitochondrial myopathies. L-carnitine: This compound facilitates fatty acid transport into mitochondria for β-oxidation, potentially mitigating metabolic crises during acute illness.[8] Antioxidants: Various antioxidant compounds may help neutralize reactive oxygen species generated by dysfunctional mitochondria, potentially reducing oxidative damage to cellular components.

In critically ill patients with MELAS, metabolic crises frequently precipitate multi-organ failure due to ATP depletion, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction. During acute decompensation, MST aims to prevent further catabolism and support mitochondrial function through several interventions. Intravenous L-arginine administration is commonly employed to mitigate stroke-like episodes by improving endothelial function and nitric oxide production.[9] High-dose dextrose infusion and TPN are frequently utilized to counteract the metabolic crisis and provide essential nutrients, though lipid-based nutrition may be limited due to potentially impaired fatty acid oxidation and the risk of hypertriglyceridemia in these patients.

Despite these interventions, the effectiveness of current MST approaches remains limited, as evidenced by the case presented, where progressive metabolic failure ultimately led to cardiogenic shock and death. This outcome highlights the urgent need for novel, targeted mitochondrial therapies that can directly enhance ATP production and mitochondrial resilience in patients with MELAS syndrome. Medications to avoid mitochondrial diseases must exercise caution with certain medications that may exacerbate mitochondrial dysfunction, increase oxidative stress, or disrupt ATP production. While no absolute contraindications exist, these drugs should be used judiciously, particularly during periods of metabolic vulnerability or acute illness.

High-risk medications for mitochondrial patients: Valproic acid: Known to cause hepatotoxicity, hyperammonemia, and mitochondrial respiratory chain inhibition. It depletes carnitine and impairs fatty acid oxidation, increasing the risk of metabolic decompensation. Statins may exacerbate myopathy by inhibiting CoQ10 synthesis and affecting mitochondrial energy production. Aminoglycoside Antibiotics (e.g., gentamicin, tobramycin): Can induce mitochondrial ribosomal dysfunction, leading to ototoxicity, nephrotoxicity, and neuromuscular blockade, particularly in individuals with preexisting mitochondrial mutations properties.[9] Erythromycin and chloramphenicol can inhibit mitochondrial protein synthesis, leading to respiratory chain dysfunction. Metformin: Inhibits mitochondrial complex I, potentially exacerbating lactic acidosis in individuals with mitochondrial disorders. Aspirin (in pediatric patients): Associated with Reye syndrome, a severe condition involving hepatic failure and encephalopathy, due to its impact on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Propofol: Associated with propofol infusion syndrome (PRIS) in mitochondrial disease, characterized by lactic acidosis, cardiac depression, and rhabdomyolysis. It disrupts fatty acid metabolism and inhibits oxidative phosphorylation.

Mechanisms of mitochondrial toxicity in common medications require close monitoring of liver function, ammonia levels, and lactate levels, which is essential when administering these drugs in patients with mitochondrial disease. Anesthesia considerations in mitochondrial disease patients with mitochondrial disorders exhibit increased sensitivity to anesthetic agents, necessitating specialized perioperative management. These patients frequently experience delayed recovery from anesthesia, respiratory depression, metabolic acidosis, and an elevated risk of perioperative complications. Key considerations for anesthesia in mitochondrial disease: Volatile anesthetics (Isoflurane, Halothane): Patients with complex I dysfunction often exhibit increased sensitivity to volatile anesthetics, requiring lower doses to achieve adequate sedation. Sevoflurane is generally better tolerated than isoflurane or halothane.[10] Propofol: While acceptable for short procedures (<30–60 minutes), prolonged infusions can precipitate propofol infusion syndrome (PRIS), characterized by lactic acidosis, hypotension, cardiac failure, and rhabdomyolysis. Its use should be minimized in patients with mitochondrial dysfunction. Benzodiazepines (Midazolam, Lorazepam): Generally well-tolerated but may cause prolonged sedation in patients with neuromuscular involvement. Ketamine: Considered relatively safe due to its ability to maintain hemodynamic stability and respiratory drive while minimizing mitochondrial toxicity.[10]

Regional anesthesia (Epidural, spinal anesthesia): Often preferred when feasible, as it avoids systemic exposure to general anesthetic agents with potential mitochondrial toxicity. Emerging therapeutic strategies: ATP restoration therapies for cardiomyocytes, with their exceptionally high energy demands, rely heavily on oxidative phosphorylation for ATP generation. In MELAS-associated cardiomyopathy, ATP depletion, oxidative stress, and calcium dysregulation contribute to contractility failure, diastolic dysfunction, and arrhythmogenesis, ultimately leading to cardiogenic shock. Several promising therapies targeting direct enhancement of ATP production and mitochondrial function are currently under investigation: EPI-743 (Vatiquinone): A para-benzoquinone derivative that modulates NAD(P) hoxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), counteracting oxidative stress and enhancing ATP synthesis. Currently under clinical investigation for various mitochondrial disorders. Sonlicromanol (KH176): A novel redox modulator designed to restore the balance of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in patients with mitochondrial disease. Idebenone: A synthetic short-chain CoQ10 analog with antioxidant properties that has demonstrated benefit in Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy and is under investigation for broader applications in mitochondrial dysfunction.[11] IV nicotinamide: A precursor of NAD+, a critical cofactor in mitochondrial metabolism, which enhances ATP production and shows promise for metabolic disorders. ATP supplementation: Preclinical studies suggest exogenous ATP administration may improve myocardial bioenergetics, reduce ischemic injury, and enhance cardiac function in settings of metabolic compromise. These emerging therapeutic approaches hold promise for addressing the fundamental bioenergetic deficits in MELAS and other mitochondrial disorders, potentially offering more effective management options for these challenging conditions.

Conclusion

This case highlights the devastating impact of MELAS-related cardiogenic shock and exposes critical limitations in current therapeutic approaches. The m.3243A>G mutation in mitochondrial tRNA-Leu (UUR) creates a fundamental bioenergetic crisis that can overwhelm conventional interventions, particularly during acute metabolic decompensation. While MST with CoQ10, riboflavin, creatine, and L-carnitine provides valuable metabolic stabilization, these approaches primarily address downstream consequences rather than core pathophysiological mechanisms. The complex interplay between heteroplasmy levels, tissue-specific energy demands, and environmental stressors creates unique management challenges in MELAS syndrome. The unpredictable threshold effects in high-energy-demanding tissues like cardiac muscle necessitate more targeted interventions that directly address ATP production deficits. This therapeutic gap becomes particularly evident during metabolic crises, where rapid progression to multi-organ failure can occur despite optimal conventional management.

Several emerging bioenergetic therapies show promise for addressing these fundamental deficits. ATP restoration strategies, including direct ATP supplementation, may potentially bypass compromised oxidative phosphorylation pathways. Novel compounds targeting oxidative stress and energy production, such as EPI-743 (vatiquinone), sonlicromanol (KH176), IV nicotinamide, and idebenone, directly address the core pathophysiology of mitochondrial dysfunction. However, these approaches require rigorous clinical validation through trials specifically designed for mitochondrial disorders. The heterogeneity and relative rarity of mitochondrial diseases present significant challenges for traditional clinical trial designs, necessitating innovative approaches like N-of-1 trials, adaptive study designs, and more sensitive outcome measures. Future investigations should prioritize evaluating these emerging therapies in MELAS-associated cardiomyopathy while incorporating a comprehensive assessment of cardiac function, tissue heteroplasmy levels, and metabolic biomarkers to identify predictors of treatment response. Improving outcomes for MELAS patients will ultimately require a multifaceted approach combining:

- Refined diagnostic protocols enable earlier intervention.

- Personalized treatment regimens based on individual heteroplasmy patterns.

- Novel therapeutics directly targeting mitochondrial ATP production.

- Preventive strategies to avoid metabolic decompensation during physiological stress.

- Comprehensive supportive care addressing the multi-system nature of the disease.

This case serves as both a sobering reminder of current therapeutic limitations and a compelling impetus for continued research and innovation in this challenging field. As our understanding of mitochondrial biology evolves, so too must our therapeutic strategies advance to address the fundamental energy crisis at the heart of these devastating disorders.

References

- Boggan RM, Lim A, Taylor RW, McFarland R, Pickett SJ. Resolving complexity in mitochondrial disease: Towards precision medicine. Mol Genet Metab. 2019;128(1-2):19–29. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2019.09.003 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- El-Hattab AW, Adesina AM, Jones J, Scaglia F. MELAS syndrome: Clinical manifestations, pathogenesis, and treatment options. Mol Genet Metab. 2015;116(1-2):4–12. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.06.004 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gallego-Delgado M, Cobo-Marcos M, Bornstein B, et al. Mitochondrial cardiomyopathies associated with the m.3243A>G mutation in the MT-TL1 gene: Two sides of the same coin. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2015;68(2):153–155. doi:10.1016/j.rec.2014.09.007 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Goto Y, Nonaka I, Horai S. A mutation in the tRNALeu(UUR) gene associated with the MELAS subgroup of mitochondrial encephalomyopathies. Nature. 1990;348(6302):651–653. doi:10.1038/348651a0 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hirano M, Ricci E, Koenigsberger MR, et al. MELAS: An original case and clinical criteria for diagnosis. Neuromuscul Disord. 1992;2(2):125–135. doi:10.1016/0960-8966(92)90045-8 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ng YS, Turnbull DM. Mitochondrial disease: genetics and management. J Neurol. 2016;263(1):179–191. doi:10.1007/s00415-015-7884-3 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ryytty S, Modi SR, Naumenko N, et al. Varied responses to a high m.3243A>G mutation load and respiratory chain dysfunction in patient-derived cardiomyocytes. Cells. 2022;11(16):2593. doi:10.3390/cells11162593 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Haas RH. The evidence basis for coenzyme Q therapy in oxidative phosphorylation disease. Mitochondrion. 2007;7(Suppl):S136–145. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2007.03.008 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Pia S, Lui F. Melas Syndrome. eBook. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Melas Syndrome

- Morgan PG, Hoppel CL, Sedensky MM. Mitochondrial defects and anesthetic sensitivity. Anesthesiology. 2002;96(5):1268–1270. doi:10.1097/00000542-200205000-00036 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Tarnopolsky MA, Parise G. Direct measurement of high-energy phosphate compounds in patients with neuromuscular disease. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22(9):1228–1233. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199909)22:9<1228::AID-MUS9>3.0.CO;2-6 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

No acknowledgments

Funding

Not applicable

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Miriam Michael

Department of Internal Medicine

Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

Email: miriambmichael@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Divya Rath, Vincent Roberts, Shivani Waghmare, Hassan Hassan, Marek Harris, Miguel Ramallo

College of Medicine

Howard University, Washington, DC, USA

Perry Kuo

Department of Internal Medicine

University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

Samrawit Zinabu, Mekdem Bisrat

Department of Internal Medicine

Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

Authors Contributions

Divya Rath, Perry Kuo, Samrawit Zinabu, Mekdem Bisrat, and Miriam Michael contributed to the conceptualization, drafting, and editing of the report. Shivani Waghmare, Vincent Roberts, Hassan Hassan, Marek Harris, and Miguel Ramallo contributed to drafting the report and editing, with Shivani Waghmare also involved in revisions. Mekdem Bisrat and Miriam Michael are also participating in revisions.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s family to discuss the current diagnosis, treatment, and the outcome of the patient’s condition in the current case report. There are no ethical concerns for this case report.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Rath D, Roberts V, Waghmare S, et al. Aiding the “Powerhouse of the Cell”: Investigating ATP Supplementation as a Potential Therapeutic Strategy in MELAS-Associated Cardiogenic Shock. medtigo J Emerg Med. 2025;2(2):e3092224. doi:10.63096/medtigo3092224 Crossref