Author Affiliations

Abstract

Over the last decades, the scientific research focus has been shifted to finding the connection between gut bacteria and brain health. The gut-brain axis connects the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) to the central nervous system (CNS), and this axis plays a critical role in neurodevelopment, mental health, and neurodegenerative disorders. The trillions of microorganisms present in the gut help to promote the health of both the digestive and nervous systems. Dysbiosis can lead to mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. In this review, methodologies used to provide valuable insights into how gut bacteria impact brain health are also included. It also emphasizes the therapeutic potential of probiotics, prebiotics, personalized treatment, and dietary modifications to maintain mental and neurological health. However, there are still issues to be resolved, such as the need for longitudinal studies, standardized research procedures, and an in-depth understanding of the mechanisms. The researcher should focus more on understanding the gut-brain axis and its utilization and finding therapeutic potential for medical breakthroughs in the treatment of various neurological disorders. This review emphasizes the importance of preserving a balanced gut microbiome for optimum brain health and identifies current research gaps and suggests future directions.

Keywords

Gut-brain axis, Gut microbiota, Mental health, Neurodevelopment, Neurodegenerative diseases, Probiotics, Neurotransmitters.

Introduction

The gut-brain axis is a complex and dynamic communication network connecting the GIT with the CNS. All neurological, hormonal, and immunological processes are influenced by the gut microbiota. Recent studies showed that the gut microbes are essential for physiological functions such as behavior and brain health [1,2]. Another research finding showed that gut microbes play a key role in modifying mental health conditions, the development of the brain, and slowing down neurodegenerative disorders [3,4].

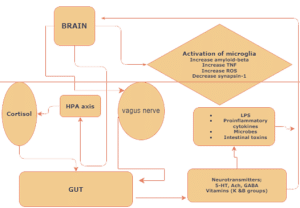

Figure 1: Illustrative diagram depicts the bidirectional connection between the gut and brain through the vagal neuronal pathway.

The proposed bidirectional communication shows the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis influencing the gut microbiota, which in turn stimulates the brain through neuropeptides, neurotransmitters, bacterial secretions, and metabolites.

The proper understanding of the gut-brain axis aids in developing possible therapeutic interventions for the treatment of brain diseases. Disorders such as depression, anxiety, stress, autism, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s are linked to the imbalance in the gut microbiota [5,6]. The mechanisms by which gut microbes impact brain function are studied through germ-free animal models, clinical trials, and sequencing technologies. For instance, the analysis of specific microbial groups associated with mental health outcomes is done by utilizing 16S Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) sequencing and metagenomics [7]. The causal effects of gut microbiota on brain development and behavior are demonstrated by using germ-free models [3,4]. Clinical trials have further highlighted the possibility of treating depression and anxiety through modifications in the gut microbiota [8].

The aim of this review is to reveal the connection between the gut and brain and to explore future research directions to find out the therapeutic potential of the gut microbiota. A detailed understanding of the gut microbiota and its influences on overall brain health could help in developing effective therapeutic strategies for myriad of neurological disorders.

| Mechanism | Description |

| Immune System Modulation | Gut microbes regulate immune responses, impacting neuroinflammation and brain health. |

| Production of Neuroactive Compounds | Gut bacteria produce neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin, gamma-aminobutyric acid [GABA]) that affect brain function. |

| HPA Axis Regulation | Gut microbiota influences stress responses by modulating the HPA axis. |

Table 1: Key Mechanisms of Gut-Brain Communication

Key Concepts and Theories

Microbiota and Neurodevelopment: Research conducted using Germ-free animal models has illustrated a notable change in brain structure and behavior in the absence of gut microbiota during early life. A study conducted by Heijtz et al. [3] and Sampson & Mazmanian [4] has shown that conventionally raised mice have better neural development and behavioral patterns as compared to germ-free mice. These findings emphasize the influence of gut microbes on the developmental process of the brain through neurotransmitter production and immune system modulation.

Microbiota and Mental Health: There is strong proof of linkage between the composition of gut microbes and mental disorders such as depression and anxiety. Research conducted by Cryan & Dinan [1] and Kelly et al. [9] has shown neuroactive substances like serotonin and GABA are produced by gut microbes, and these substances regulate the mood and emotional responses. The increased susceptibility to psychiatric disorders has been associated with dysbiosis, or an imbalance in gut microbiota composition. A clinical trial conducted by Romijn et al. [8] demonstrated that probiotics can improve mood and reduce symptoms of depression. These findings highlight that the treatment of mental disorders can be done by modifying gut microbes.

Microbiota and Neurodegenerative Diseases: The neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, have been associated with imbalances in the gut microbiota. The neuronal inflammation, protein aggregation, and neuronal damage are associated with specific bacterial strains and microbial metabolites [6,10]. Scheperjans et al. [6] compared the gut microbiota composition between healthy controls and Parkinson’s disease patients and concluded that there is a difference in composition of the gut microbiota between these individuals and suggested a potential role of the microbiota in disease susceptibility. According to Agahi et al. [11], probiotics improve cognitive function in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. A study has suggested that the ecological balance of gut flora regulates neurotropic factor expression. It has also been shown that gut flora is involved in regulating the microbiota-gut-brain (MGB) axis and suppressing inflammation [20].

| Gut microbiota composition | Reference |

| Firmicutes, Actinobacteria phylum and Eubacteriumrectale↓; Bacteroides and Shigella ↑ | Cattaneo et al. [21] |

| Prevotella, Sutterella, Haemophilus↓ | Paley [22] |

| Escherichia-Shigella and Desulfovibrio↑ | Chen et al. [23], Borsom et al. [24] |

| Pseudomonas, Faecalibacterium, Fusicatenibacter, Blautia, and Dorea↑ | Xi et al. [25] |

| Candidatus Saccharibacteria phylum and Proteobacteria ↑ | Heravi, Naseri & Hu [26] |

| Saccharibacteria, Anaerotruncus, Vampirovibrio, and Alistipes ↑;Dorea, Anaerostipes, Hallella, and Ruminococcus↓ | Favero et al. [27] |

| Helicobacter pylori↑ | Xie et al. [28] |

Table 2: Gut microbiota composition in patients with Alzheimer’s disease

Gut Microbiota and Brain-Gut Interactions: Collins et al. [13] reviewed the effects of the gut microbiome on brain-gut interactions, highlighting bidirectional interactions and suggesting that dysbiosis may contribute to the development of mental illness, including depression and anxiety.

Gut Microbiota’s Role in Anxiety and Mood Disorders: According to Bercik et al., gut microbiota can influence behavior in mice, suggesting that bacterial infections can induce anxiety-like behaviors, which can be reversed by antibiotic treatment [14].

Probiotics and Neuroplasticity: Neufeld et al. determined that Bifidobacterium longum, a probiotic, decreased anxiety-like behavior in mice and normalized brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels inside the hippocampus, indicating a connection between gut microbiota and neuroplasticity [15].

Gut Microbiota and Stress Regulation: Sudo et al. demonstrated that colonization of the gut with specific bacterial strains can modulate the body’s stress response. It suggests that to maintain a balanced HPA axis, a healthy gut microbiome is essential [16].

Probiotics and Mental Health: Research has shown that probiotics can improve mental health. A study by Bravo et al. [17] found that long-term treatment with Lactobacillus rhamnosus, a probiotic, reduced anxiety and depression-like behavior in mice by influencing GABA receptor expression in the brain. Similarly, Forsythe et al. [18] found that probiotics could attenuate inflammation and behavioral modifications induced by early life stress in animal models, suggesting that probiotics may also offer a promising healing pathway for treating mood disorders.

Gut Microbiota and Cognitive Function: The gut microbiota plays a significant role in cognitive function. Gareau et al. [19] observed that postnatal colonization of germ-free mice with gut microbiota from control animals has shown improvement in cognitive function and reduced anxiety-like behavior. This result indicates that a healthy gut microbiome is important for emotional regulation and cognitive development, and functioning.

Methodology

Instruments and Methods

Germ-free (GF) Animal Models: GF models enable researchers to introduce specific microbes and examine their physiological and psychological effects. Research conducted by Heijtz et al. [3] has demonstrated that the conventionally raised mice have normal brain development and behavior as compared to germ-free mice. When these GF mice are introduced to a normal gut microbiota, their behavior is also normalized. Hence, this research suggests the importance of microbiota in the development of the brain and behavior. Sampson et al. [4] revealed that the introduction of microbiota from Parkinson’s disease patients into GF mice has developed motor deficits and neuroinflammation, concluding the role of microbiota in disease pathology. The impact of gut microbiota from depressed patients on GF rats was studied by Kelly et al. [9] who highlighted that GF rats showed depression-like behavior and suggested the direct influence of microbiota on mental health.

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT): FMT is a method of transferring the gut microbiota of a healthy donor to a recipient. Research carried out by Kang et al. [12] showed that autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is treatable. They observed an improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms and behavioral outcomes following transplantation in ASD patients. The study’s purpose is to establish the effectiveness of FMT in treating ASD symptoms. They suggest that FMT will also be beneficial for the treatment of other mental problems like depression, anxiety, and Parkinson’s.

Clinical Trials with Probiotics and Prebiotics: Recent clinical trials have demonstrated the benefit of probiotics and prebiotics in the treatment of depression and anxiety. Romijn et al. [8] conducted a controlled clinical trial to assess the efficacy of probiotics on depression and anxiety. The depression patients were administered probiotics containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 and Bifidobacterium lactis HN019. They found that symptoms of depression and anxiety decreased as compared to the placebo group. It is also observed that probiotics have anti-inflammatory and stress-reducing effects.

Sequencing Technologies: With the advancement in technologies, the study of gut microbiota to get insight into microbial diversity, their stability, and metabolic capabilities has become easier. The advanced sequencing technologies, such as 16S rRNA sequencing and metagenomics, are used for detailed examination of gut microbes. Valles-Colomer et al. [7] found that specific microbial species were associated with depression by utilizing metagenomic sequencing technologies. They also uncovered functional pathways related to neurotransmitter metabolism and inflammation through which gut microbes impact mental health.

Neuroimaging Assessments: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain structure and function is better understood with the utilization of neuroimaging techniques such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scan. The proper investigation of the gut-brain axis requires advanced techniques, such as neuroimaging. Kelly et al. [9] used a neuroimaging technique and found that regions associated with mood regulation were impacted by changes in gut microbial composition.

| Study Year | Authors | Key Findings | Methodology |

| 2011 | Heijtz et al. | Gut microbiota influences brain development and behavior | Germ-free animal models |

| 2012 | Cryan & Dinan | Gut microbiota impacts mental health through neurotransmitter production | Review of existing studies |

| 2015 | Sampson & Mazmanian | Absence of gut microbiota leads to altered brain structure and function | Germ-free animal models |

| 2016 | Kelly et al. | Depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioral changes | Animal models |

| 2017 | Romijn et al. | Probiotics reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety | Clinical trial |

| 2017 | Kang et al. | Microbiota Transfer Therapy alters gut | Open-label study |

| 2018 | Agahi et al. | Probiotic supplementation improves cognitive function in mild cognitive impairment | Clinical trial |

| 2019 | Valles-Colomer et al. | Gut microbiota’s neuroactive potential affects quality of life and depression | Microbiome analysis |

Table 3: Key Findings and Methodology

Discusssion

Applications and Implications

Probiotics and Prebiotics: Promising treatments for brain health because they alter gut microbiota composition and alleviate symptoms of mental and neurological illnesses. Clinical trials have demonstrated that probiotic supplementation with strains can alleviate depression and anxiety symptoms. Prebiotics, which are present in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, encourage the growth of healthy gut bacteria, improving overall gut health and indirectly enhancing brain function.

Dietary Treatments: Such as fiber-rich meals, fermented foods, and polyphenol-rich sources like green tea and berries have all been linked to a diverse and beneficial gut flora. These components act as substrates for microbial fermentation in the gut, creating metabolites such as Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that have anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties.

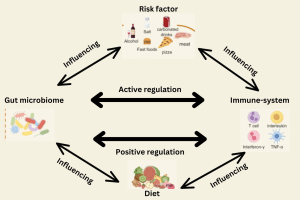

Figure 2: Microbiota-targeting therapies and influencing factors

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM): Treatments regulate the gut microbiota and are increasingly applied in clinical practice. Studies have demonstrated that traditional Chinese medicine modulates gut microbiota function and composition, benefiting overall brain health.

| TCM formula | Impact on gut microbiota | Impact on cognitive function | Reference |

| Huanglian Jiedu Decoction | Prevotellaceae and its genus Prevotellaceae_UCG-001↑, Prevotellaceae_Ga6A1_group, and Parasutterella↑ | Suppressed Aβ accumulation, harnessed neuroinflammation, and reversed cognitive impairment | Gu et al. [29] |

| Liuwei Dihuang Bolus | Bacteroides and Parabacteroides ↓ Acidiphilium↑

|

Delayed ageing processes, improved cognitive impairments, and balanced the neuroendocrine immunomodulation system | Wang et al. [30] |

| Xiao yao san | Alpha diversity and the relative abundance of Lachnospiraceae↑ | Improved cognitive function, including shortened escaped latency and increased number platforms crossed | Hao et al. [31] |

| Shu Dihuang | Bacteroidetes, Bacteroidia ↑ Firmicutes and Bacill ↓ | Improved cognitive dysfunction and brain pathological changes | Su et al. [32] |

| Chaihu Shugan San | The relative abundance of L. reuteri significantly ↑ the relative abundance of S. xylosus↓ | improved the memory deficits and the learning function and ameliorated neuronal injury, synaptic injury, and Aβ deposition in the brain of SAMP8 mice | Li et al. [33] |

Table 3: TCM and its impact on gut microbiota and cognitive function

Weaknesses and Gaps in Research

Lack of Longitudinal Studies: Longitudinal studies are important to understand the relationship between gut bacteria and brain health because they track microbial changes over time and how they affect brain function. These studies contribute to the understanding of microbial dynamics throughout the life cycle and establish causal relationships.

Heterogeneity in Study Designs: Differences in study design, such as number of participants, sample size, and methods used to assess microbial composition, contribute to the diversity of study findings. Sample collection, methods, sequencing, and data analysis design standards are needed to ensure reproducibility and robustness in microbiological studies by addressing methodological inconsistencies and systematic review and weakening that evidence, and to elucidate the impact of gut microbiota on specific neurological conditions [1].

Mechanistic Understanding: Although links between the gut microbiota and brain health have been established, the mechanisms underlying these interactions are poorly understood. Mechanistic studies are needed to explain how metabolites are derived from microbial, immune, and neural signaling pathways and affect brain function and behavior. Advanced approaches such as microbiome metabolism and neuroimaging combined with genetic manipulation in animal models may provide mechanistic insights into the causal relationship between the gut microbiota and neurodegenerative disease [4].

Translation from Animal Models to Human Applications: Translation of findings from animal studies to human clinical applications represents a major challenge for microbiota research. While animal models, especially germ-free models, provide valuable insights into basic mechanisms, the human microbiome and environment are highly diverse and thus require rigorous clinical trials with well-defined patient cohorts to validate preclinical findings and evaluate the efficacy of microbiota-targeted interventions in larger populations. Establishing compelling evidence from human research can be essential for directing healthcare practices and regulatory decisions regarding microbiota-based treatment plans.

Future Trends and Challenges

Advanced Sequencing and Bioinformatics: The advancement of sequencing technologies, combined with advanced bioinformatics tools, will help to revolutionize our knowledge of microbiota composition and characteristics in relation to brain health. High-throughput sequencing techniques, together with metagenomics and transcriptomics, allow complete profiling of microbial communities and their genetic capabilities.

Translating Preclinical Findings: Translating findings from preclinical models to clinical applications represents a major challenge in microbiota research. Although animal studies provide fundamental insights into microbiota-brain interactions, species-specific differences in gut microbiota composition and immune response require caution while translating the interpretation in a human context. Future efforts should prioritize large, multicenter clinical trials with diverse patient populations to confirm preclinical findings and assess safety, efficacy, and the long-term effects of microbiome-based interventions.

Ethical and Regulatory Considerations: The implementation of microbiota-based therapies increases ethical considerations concerning consent, privacy, and the potential for accidental consequences. Agahi et al. [11] emphasized the need for effective oversight and strong regulatory frameworks to minimize the risks associated with microbial therapies, build public confidence, and facilitate accurate access to emerging therapies.

Conclusion

This review article on the gut-brain axis revealed profound links between gut bacteria and brain health. Utilization of technologies such as advanced sequencing, and neuroimaging techniques helps to understand in-depth gut microbiota composition and its relation to various neurological disorders. Extensive research took place to show that changes in the gut microbiota could affect cognitive functioning, psychological distress, and neurodevelopmental conditions. Clinical trials and studies have provided compelling evidence for the therapeutic potential of probiotics and dietary intervention to alter the gut microbiota to improve gastrointestinal symptoms, behavioral outcomes, and mental health. Advances in neuroimaging, such as MRI and PET scans, allow researchers to understand how microbial changes in the gut could impact brain structure and function. Future research should delve into the development of microbiota-based therapies for the treatment of brain-related disorders and to enhance the overall mental health of the individual.

References

- Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behavior. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(10):701-712. doi:10.1038/nrn3346 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mayer EA, Knight R, Mazmanian SK, Cryan JF, Tillisch K. Gut microbes and the brain: Paradigm shift in neuroscience. J Neurosci. 2014;34(46):15490-15496. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3299-14.2014 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Heijtz RD, Wang S, Anuar F, et al. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(7):3047-3052. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010529108 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sampson TR, Mazmanian SK. Control of brain development, function, and behavior by the microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17(5):565-576. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.011 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Foster JA, Neufeld KAM. Gut-brain axis: How the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36(5):305-312. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2013.01.005 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Scheperjans F, Aho V, Pereira PA, et al. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson’s disease and clinical phenotype. Mov Disord. 2015;30(3):350-358. doi:10.1002/mds.26069 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Valles-Colomer M, Falony G, Darzi Y, et al. The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4(3):623-632. doi:10.1038/s41564-018-0337-x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Romijn AR, Rucklidge JJ, Kuijer RG, Frampton C. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of Lactobacillus helveticus and Bifidobacterium longum for the symptoms of depression. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51(8):810-821. doi:10.1177/0004867416686694 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kelly JR, Borre Y, O’Brien C, et al. Transferring the blues: Depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;82:109-118. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.07.019 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wang Y, Kasper LH. The role of microbiome in central nervous system disorders. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;38:1-12. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2013.12.015 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Agahi A, Hamidi GA, Daneshvar R, et al. Does severity of Alzheimer’s disease contribute to its responsiveness to modifying gut microbiota? A double blind clinical trial. Front Neurol. 2018;9:662. doi:10.3389/fneur.2018.00662 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kang DW, Adams JB, Gregory AC, et al. Microbiota Transfer Therapy alters gut ecosystem and improves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms: An open-label study. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):10. doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0225-7 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Collins SM, Surette M, Bercik P. The interplay between the intestinal microbiota and the brain. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(5):356-366. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2100 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bercik P, Denou E, Collins J, et al. The intestinal microbiota affect central levels of brain-derived neurotropic factor and behavior in mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(2):599-609. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.052 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Neufeld KA, Kang N, Bienenstock J, Foster JA. Effects of intestinal microbiota on anxiety-like behavior. Commun Integr Biol. 2011;4(4):492-494. doi:10.4161/cib.4.4.15702 PubMed | Google Scholar

- Sudo N, Chida Y, Aiba Y, et al. Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. J Physiol. 2004;558(1):263-275. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2004.063388 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bravo JA, Forsythe P, Chew MV, et al. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(38):16050-16055. doi:10.1073/pnas.1102999108 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Forsythe P, Sudo N, Dinan T, Taylor VH, Bienenstock J. Mood and gut feelings. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(1):9-16. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2009.05.058 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gareau MG, Wine E, Rodrigues DM, et al. Bacterial infection causes stress-induced memory dysfunction in mice. Gut. 2011;60(3):307-317. doi:10.1136/gut.2009.202515 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Zou X, Zou G, Zou X, Wang K, Chen Z. Gut microbiota and its metabolites in Alzheimer’s disease: From pathogenesis to treatment. 2024;12:e17061. doi:10.7717/peerj.17061 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Cattaneo A, Cattane N, Galluzzi S, et al. Association of brain amyloidosis with pro-inflammatory gut bacterial taxa and peripheral inflammation markers in cognitively impaired elderly. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;49:60-68. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.08.019 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Paley EL. Discovery of gut bacteria specific to Alzheimer’s associated diseases is a clue to understanding disease etiology: Meta-analysis of population-based data on human gut metagenomics and metabolomics. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;72:e319-355. doi:10.3233/JAD-190873 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Chen Y, Fang L, Chen S, et al. Gut microbiome alterations precede cerebral amyloidosis and microglial pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:e8456596. doi:10.1155/2020/8456596 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Borsom EM, Conn K, Keefe CR, et al. Predicting neurodegenerative disease using prepathology gut microbiota composition: A longitudinal study in mice modeling Alzheimer’s disease pathologies. Microbiol Spectr. 2023;11:e0345822. doi:10.1128/spectrum.03458-22 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Xi J, Ding D, Zhu H, et al. Disturbed microbial ecology in Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence from the gut microbiota and fecal metabolome. BMC Microbiol. 2021;21:e226. doi:10.1186/s12866-021-02286-z PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Heravi FS, Naseri K, Hu H. Gut microbiota composition in patients with neurodegenerative disorders (Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s) and healthy controls: A systematic review. Nutrients. 2023;15(20):e4365. doi:10.3390/nu15204365 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Favero F, Barberis E, Gagliardi M, et al. A metabologenomic approach reveals alterations in the gut microbiota of a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0273036. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0273036 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Xie J, Cools L, Van Imschoot G, et al. Helicobacter pylori-derived outer membrane vesicles contribute to Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis via C3-C3aR signalling. J Extracell Vesicles. 2023;12:e12306. doi:10.1002/jev2.12306 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gu X, Zhou J, Zhou Y, et al. Huanglian Jiedu decoction remodels the periphery microenvironment to inhibit Alzheimer’s disease progression based on the brain-gut axis through multiple integrated omics. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2021;13:e44. doi:10.1186/s13195-021-00779-7 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wang J, Lei X, Xie Z, et al. CA-30, an oligosaccharide fraction derived from Liuwei Dihuang decoction, ameliorates cognitive deterioration via the intestinal microbiome in the senescence-accelerated mouse prone 8 strain. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11:e3463-3486. doi:10.18632/aging.101990 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Hao W, Wu J, Yuan N, et al. Xiaoyaosan improves antibiotic-induced depressive-like and anxiety-like behavior in mice through modulating the gut microbiota and regulating the NLRP3 inflammasome in the colon. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:e619103. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.619103 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Su Y, Liu N, Sun R, et al. Radix Rehmanniae Praeparata (Shu Dihuang) exerts neuroprotective effects on ICV-STZ-induced Alzheimer’s disease mice through modulation of INSR/IRS-1/AKT/GSK-3β signaling pathway and intestinal microbiota. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:e1115387. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1115387 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Li Z, Zeng Q, Hu S, et al. Chaihu Shugan San ameliorated cognitive deficits through regulating gut microbiota in senescence-accelerated mouse prone 8. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:e1181226. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1181226 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

First, we acknowledge the authors and researchers whose work has laid the foundation for this review. We express our gratitude for their contribution in the medical field and for playing a key role in advancing the understanding of the gut microbiota and its role in mental health. We would like to thank all contributors who supported completing this review article.

Lastly, we are grateful to our institution, mentors, colleagues, families, and friends for their unwavering support and encouragement. With their invaluable assistance only, we have successfully completed this endeavor.

Funding

None

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Sannu Ahmed

Department of Pharmacy

National Academy for Medical Sciences, Old Baneshwor, Kathmandu, Nepal

Email: pr.sannu.ahmed@gmail.com

Co-Author:

Pradip Regmi

Department of Pharmacy

Nepal Institute of Health Sciences, Jorpati, Kathmandu, Nepal

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Not applicable

Guarantor

Not applicable

DOI

Cite this Article

Sannu A, Pradip R. Advancements in Gut Microbiota Research: A Critical Review. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(3):e3062236. doi:10.63096/medtigo3062236 Crossref