Author Affiliations

Abstract

Aim: This study aimed to determine factors that contribute to antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Ghana.

Design: This study employed a systematic review methodology.

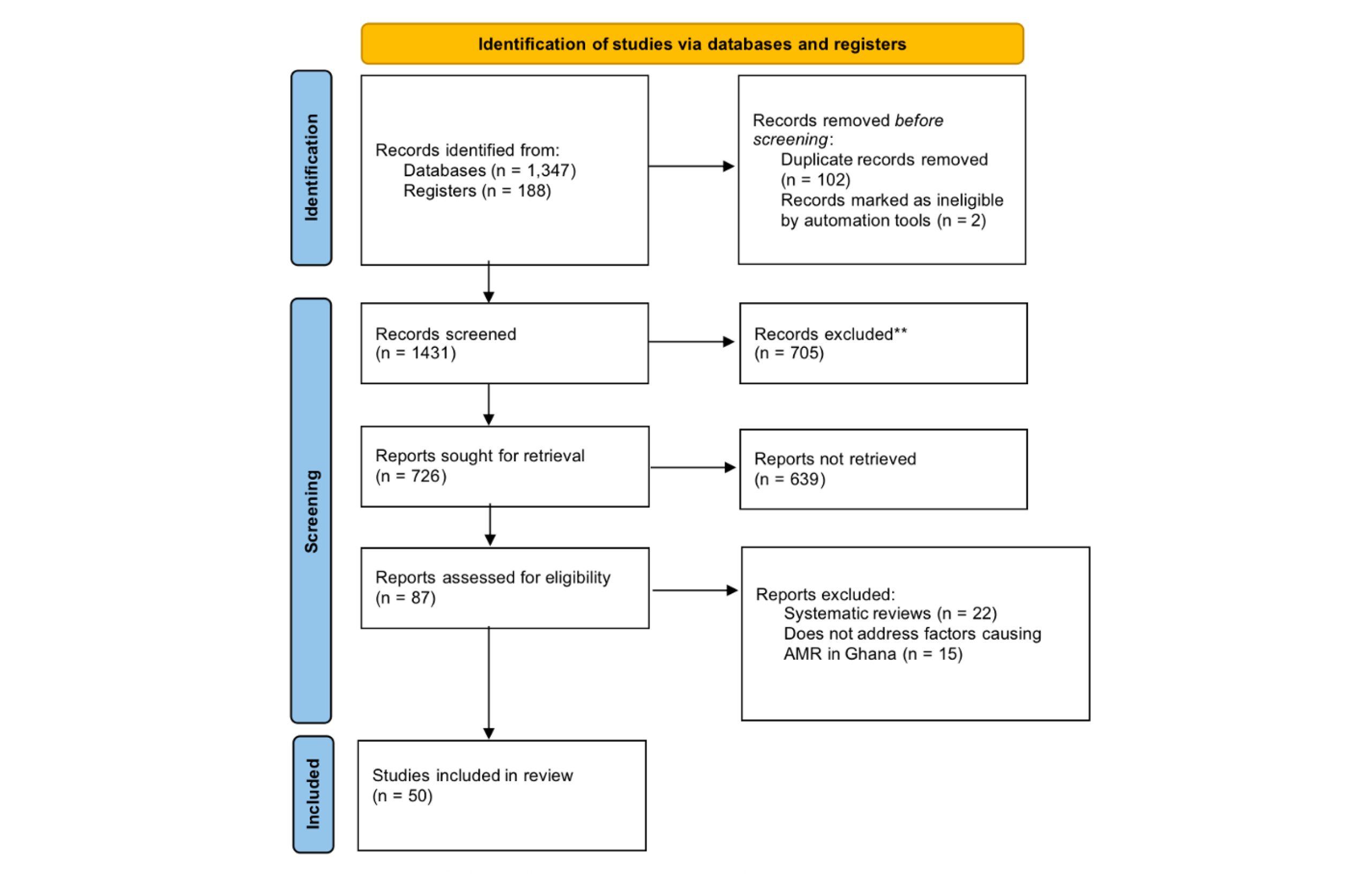

Methodology: A systematic search of five electronic databases was conducted, adhering to Cochrane Library guidelines (PubMed/Medline, Scopus, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, and Cochrane) from 2013 to 2023. The remaining articles were subjected to rigorous data extraction and subsequently analyzed thematically. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram was utilized to visualize the study selection process. The review included English-language studies published between 2013 and 2023.

Results: Four primary themes emerged as significant contributors to AMR: healthcare-associated AMR, community-associated AMR, agricultural AMR, and emerging threats to antibiotic efficacy. Urgent and comprehensive interventions are essential to mitigate Ghana’s growing threat of AMR. These include promoting responsible antibiotic prescribing practices in healthcare settings, educating communities about appropriate antibiotic use and hygiene, strengthening veterinary oversight in the agricultural sector, and investing in research and development to discover novel antibiotics.

Conclusion: This systematic review highlights the multifactorial drivers of AMR in Ghana, including misuse of antibiotics, poor sanitation, and knowledge gaps across health, community, and agricultural sectors. Most studies focus on urban referral hospitals; thus, broader research and urgent, coordinated interventions nationwide are vital to preserve antibiotic effectiveness.

Keywords

Antimicrobial resistance, Medications, Life-threatening infections, Databases, Cochrane Library guidelines.

Introduction

From preventing life-threatening infections to keeping food safe, antimicrobials are the guardians of our health. What are antimicrobials? Antimicrobial medications are chemical substances that demonstrate potent activities against a range of microbes, encompassing both elimination and growth inhibition, with a targeted focus on clinically relevant pathogens.[1] Ubiquitous, microscopic life forms- microbes- are found in water, soil, air, and even within the human body. They influence our health in two ways, either as our friend or enemy. Some are our essential partners, aiding digestion and immunity, while others wage war, causing infections. Understanding this microscopic dance is crucial for our health and is key to combating disease.[2,3]

Mechanism of antimicrobial medications: Microbes initiate infection through a carefully orchestrated sequence. First, they navigate host tissues via chemotaxis and other targeted cues, ultimately colonizing specific niches through adhesin-mediated attachment. Rapid replication ensues, fueled by efficient nutrient acquisition from the host environment. The final twist lies in immune evasion, where diverse strategies like antigenic variation and immune suppression allow microbes to persist and thrive.[4] Antimicrobials help stop the growth of microbes and are classified into two mechanisms: the swift kill of microbicidal agents, breaching defenses and ensuring cellular collapse, and the subtle sabotage of microbistatic ones, crippling growth and leading to a gradual decline. Both uniquely neutralize the microbial threat, one with a decisive blow and the other with a controlled descent.[5] Antimicrobial medications, including antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals, and antiparasitics, are crucial in preventing and treating infectious diseases across a diverse spectrum of life, encompassing humans, animals, and plants. But over time, some of these microbes no longer respond to the antimicrobial medication, making it harder to treat infections, leading to the term AMR.[6] For resistance to occur, some microbes develop biochemical pumps that remove antimicrobial drugs before they work, while others produce enzymes that inactivate the medications. This resistance makes infections tougher to beat, sometimes impossible, raising the risk of spread, illness, and even death. At the same time, inherent to microbial evolution, emerging antimicrobial resistance is significantly amplified by the interplay of drug exposure and microbial dissemination.[7]

Background: AMR has risen to become a leading public health threat, directly claiming over 1.27 million lives in 2019 and contributing to nearly 5 million additional deaths. Beyond the human cost, AMR incurs significant economic burdens. The World Bank estimates potential healthcare costs will exceed $1 trillion by 2050, and annual gross domestic product (GDP) losses will reach $3.4 trillion by 2030.[8,9] Beyond the inherent high cost of antimicrobial research and development, AMR’s rapid evolution has choked investment returns for pharmaceutical companies. This resistance cliff, where new drugs face limited efficacy and profitability, has driven numerous companies to abandon antimicrobial development altogether, creating a critical gap in the pipeline.[10]

Within the World Health Organization’s (WHO) regional framework, Africa bears the brunt of the global AMR burden.[11] An estimated 4.1 million lives in Africa are projected to be lost to antimicrobial resistance by 2050, highlighting the significant public health burden of this emerging threat. Though present in most African nations, national action plans fall short against AMR due to weak political commitment, insufficient surveillance infrastructure, and limited capacity for optimized antibiotic use and public awareness. Furthermore, inadequate infection control, poor water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) services exacerbate the issue.[12] Low-and middle-income countries like Ghana bear a weighty AMR burden, jeopardizing healthcare and patient outcomes. AMR in these settings fuels increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs, further straining already limited resources.[13] A recent sentinel site study in Ghana paints a concerning picture of AMR within Gram-negative bloodstream infections. A staggering 88% of isolated bacteria exhibited multi-drug resistance, with alarming resistance rates ranging from 56-78% for third-generation cephalosporins, a critical class of antibiotics.[14] Despite existing legislation regulating antibiotic sales in Ghana, weak enforcement remains a formidable obstacle. The primary culprit? Inadequate funding to monitor compliance with established regulations. Additionally, self-medication remains a pressing public health issue in Ghana, with a significant prevalence rate that remains unresolved.[15,16] This insufficient budgetary support hinders effective oversight, allowing gaps in enforcement to persist and potentially contribute to the ongoing challenge of antimicrobial resistance.

Understanding the drivers of AMR in Ghana is crucial for crafting effective interventions to address its high prevalence and optimize antibiotic usage. This review aims to delve into the key factors contributing to AMR in the Ghanaian context, pinpointing areas demanding further research to inform robust and targeted solutions.

Methodology

Study population: Ghana is in West Africa with approximately 32 million inhabitants.[17] This population is distributed among the coastal plains of the south to the savannas and forest areas of the north. The bustling urban centers like Accra hum with activity, while the vast rural communities paint a contrasting picture of potential disparities in healthcare access and antibiotic use.[18,19] Ghana comprises sixteen administrative regions, each with unique characteristics and challenges from the urban centers of Accra to the rural communities in the Upper East region.[20] Ghana, classified as a lower-middle-income country, faces significant challenges within its healthcare system, contributing to the rise of antimicrobial resistance, such as a shortage of healthcare personnel and limited access to essential medicines.[21,22] All these factors create a breeding ground for the ineffectiveness of antibiotics in treating common infections.

Search strategy: This systematic review adhered to the rigorous methodological standards outlined by the Cochrane Library guidelines. To ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant literature, this systematic review utilized five databases: PubMed/Medline, Scopus, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, and Cochrane. Search strategies were tailored to teach the database using appropriate keywords and indexing terms. The search strategy employed Boolean operators (AND and OR) to optimize the retrieval of relevant literature related to AMR. Key terms included “antimicrobials (antibiotics, antifungals, antivirals, antiparasitic)”, “resistance”, “Ghana”, “Ghanaians”, “drugs”, “medications”, “stewardship”, causes, determinants, or factors. These were used to identify impactful studies investigating the multifaceted drivers of AMR.

Selection criteria: This review adopted an inclusive approach, encompassing studies of all methodological types (qualitative, quantitative, mixed-methods) across diverse global contexts. This comprehensive strategy aimed to capture the full spectrum of research investigating AMR in Ghana, ensuring insightful findings. This review systematically examined literature published from January 1, 2013, to August 31, 2023, encompassing peer-reviewed journals, published books, and WHO reports relevant to AMR globally and in Ghana. The selection criteria prioritized studies in the English language with full-text availability that directly addressed the research questions of this review.

To ensure the review’s focus on current, readily accessible, and directly relevant research, systematic reviews and studies lacking full-text availability were excluded. Additionally, the scope was strictly limited to AMR in Ghana, excluding information on AMR in other countries.

Selection process: Initial article selection commenced with a meticulous screening of titles and abstracts to identify studies relevant to this review’s scope. Following title and abstract screening, the remaining articles underwent a full-text evaluation against the established inclusion and exclusion criteria. Identified duplicate articles or studies were eliminated, and only relevant selections were retrieved and saved for further analysis. Additionally, the bibliographies of these articles were scrutinized to identify potentially relevant publications not captured by the initial database search. A total of 50 articles were retrieved, comprehensively exploring the drivers and consequences of AMR in Ghana. These encompass analyses of AMR’s impact across diverse sectors (agriculture, healthcare settings, individual health, and economic ramifications), alongside proposed interventions and mitigation strategies.

Following careful selection, the identified articles were systematically organized into thematic categories. PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2) was adopted to ensure transparency in the review process.[23] A dedicated data extraction sheet was developed to capture key information from each article to facilitate further analysis and thematic exploration.

| Primary study design category | Count | Percentage (%) |

| Cross-Sectional Survey/Study | 20 | 40.0 |

| Retrospective Cross-Sectional / Audit | 10 | 20.0 |

| Point Prevalence Survey (PPS) | 5 | 10.0 |

| Mixed Methods (Quant. + Qual.) | 5 | 10.0 |

| Qualitative Research | 3 | 6.0 |

| Cross-Sectional Laboratory/Surveillance | 3 | 6.0 |

| Environmental/Molecular Surveillance | 3 | 6.0 |

| Prospective Cohort / Quasi-Experimental | 1 | 2.0 |

| Total unique studies | 50 | 100.0 |

Table 1: General characteristics of the study

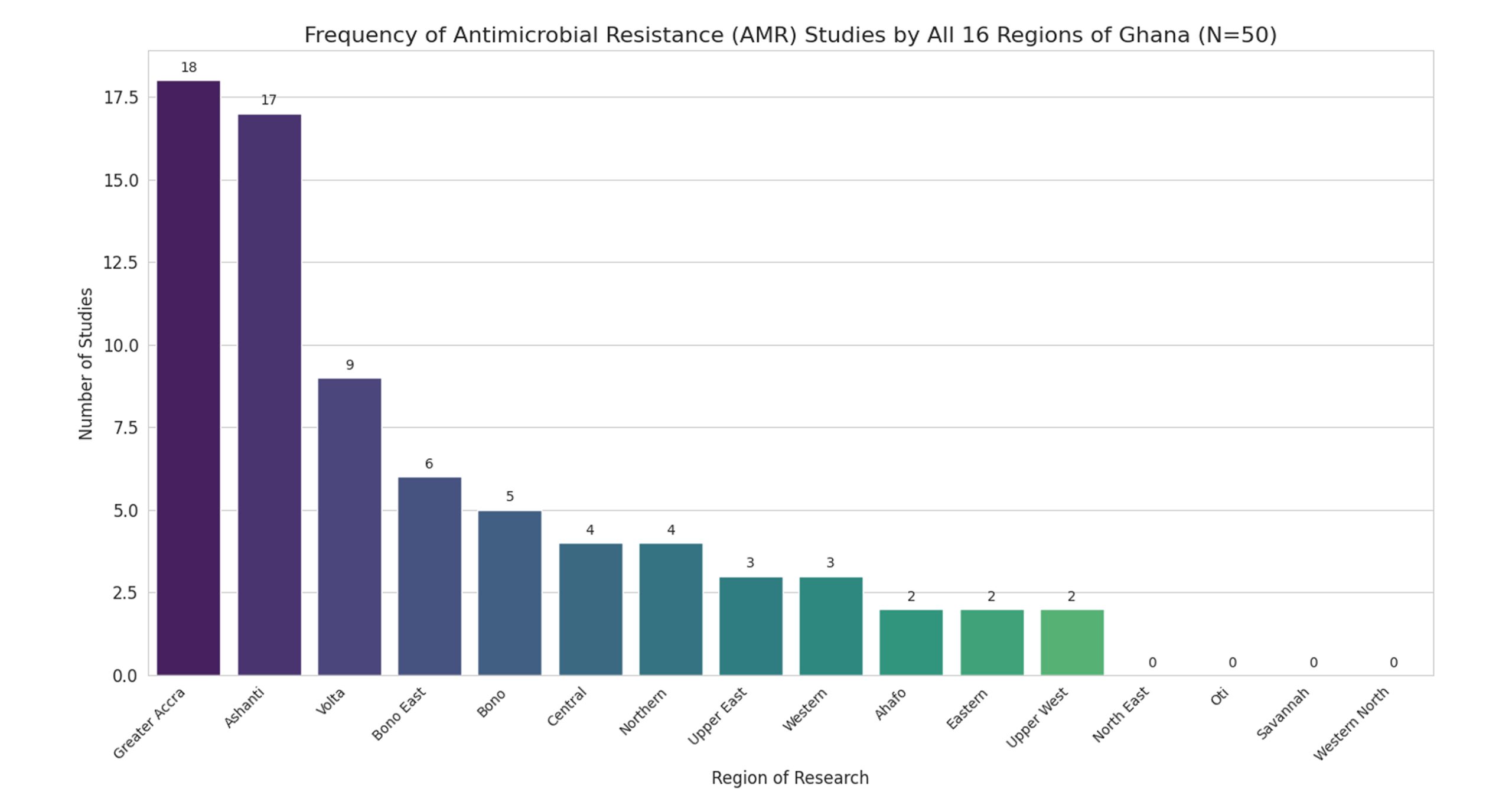

Figure 1: Study population by different regions

Figure 1 shows a geographical finding that reveals a severe imbalance in AMR research, with 70% of study assignments concentrated in the Greater Accra and Ashanti regions. This bias towards major urban centers leaves four of Ghana’s 16 regions – North East, Oti, Savannah, and Western North – with zero studies, representing a critical national surveillance gap.

Figure 2: Article search and selection process

Results

This review explored the latest research on factors contributing to AMR in Ghana, focusing exclusively on studies published from 2013 to 2023 to reflect the most recent dynamics and evidence. Table 1 illustrates the distribution of research methodologies employed within the reviewed studies. This research was dominated by observational quantitative methods, which comprise nearly 70% of all studies. The most frequent design was the cross-sectional survey/study at 40.0%, primarily used to capture a snapshot of knowledge or prevalence. A significant portion was dedicated to evaluating clinical practice, with retrospective audits (20.0%) and point prevalence surveys (PPS; 10.0%) measuring compliance and antibiotic consumption in healthcare facilities. Beyond quantifying the problem, the field adopted a holistic approach by utilizing mixed methods (10.0%) and qualitative research (6.0%) to explore the behavioral and social drivers of misuse. Finally, laboratory and environmental surveillance studies (12%) confirmed research is being conducted under the “One Health” framework to track resistance in clinical, animal, and environmental settings.

Healthcare-associated AMR (Human health/Clinical):

| Reference no. | Study | Population | Outcome definition | Total (N) | Inappropriate cases (k) | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI | Weight (%) |

| 19 | Sefah et al. | Surgical inpatients (SAP) | Non-compliance (Duration) | 597 | 582 | 97.5 | (96.2 – 98.7) | 1.9 |

| 21 | Hope et al. | Specialist eye hospital | Inappropriate decision to prescribe | 111 | 32 | 28.8 | (20.6 – 38.2) | 0.8 |

| 25 | Owusu et al. | Polyclinic (UTI patients) | Failure to meet all STG components | 3073 | 1226 | 39.9 | (38.0 – 42.0) | 10.1 |

| 45 | Amponsah et al. | Outpatient dept. (WHO/INRUD) | Antibiotic prescribed per encounter | 23,281 | 9,994 | 43.0 | (42.4 – 43.6) | 87.2 |

| Pooled estimate | Random-effects model | All settings combined | Overall suboptimal practice | 27,062 | 11,834 | 44.9 | (30.6 – 59.8) | 100.0 |

Table 2: Pooled analysis – Suboptimal antibiotic prescribing practice

This table shows the high burden of poor antibiotic prescribing practices in Ghana (pooled estimate: ≈ 45%). It aggregates different types of errors—such as prescribing the drug too frequently, for the wrong duration, or failing to meet official guidelines—to quantify the overall quality deficit in antibiotic use within healthcare settings.

| Reference no. | Study | Population | Total inpatients (N) | Patients on antibiotics (k) | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI` | Weight (%) |

| 31 | Labi et al. | Multi-center PPS (Pediatric) | 716 | 506 | 70.6 | (67.1-74.1) | 16.9 |

| 34 | Labi et al. | Multi-center PPS (7 hospitals) | 2,752 | 1,827 | 66.4 | (64.6-68.1) | 59.9 |

| 43 | Amponsah et al. | Multi-center PPS (3 hospitals) | 190 | 115 | 60.5 | (53.5–67.5) | 12.3 |

| 46 | Dodoo et al. | Ho teaching hospital (Inpatient PPS) | 239 | 163 | 68.2 | (62.0-74.0) | 10.9 |

| Pooled estimate | Random-effects model | Overall inpatient antibiotic use (AMU) | 3,897 | 2,611 | 67.0 | (64.1-69.8) | 100.0 |

Table 3: Pooled analysis – Antibiotic use prevalence in inpatients (Proportion of patients receiving ≥1 antimicrobial on survey day)

The above table shows AMU is near-universal in Ghanaian hospitals, with a highly precise pooled estimate of 67.0%. Two out of three inpatients are exposed to antibiotics on any given day, underscoring a critical need for large-scale Antimicrobial Stewardship. A significant number of the research results show that factors associated with healthcare-associated AMR are as follows: prescription adherence behaviors; a research result from the analyzed findings revealed a significant correlation between poor adherence to prescribed medications and several healthcare worker-related factors. These factors included ineffective communication strategies that emphasized illness severity and fear-mongering, as well as inadequate explanations regarding medication instructions, gaps in knowledge, and attitude of AMR among prescribers; variability in prescribers’ knowledge of antimicrobials emerges as a significant contributor to antimicrobial resistance as seen in these two results [23-29]. This variability likely stems from differences in prescriber experience, which can influence their understanding of the appropriate medication selection based on the causative organism, gaps in prescription patterns; a review of ten studies revealed a concerning association between inappropriate prescribing patterns and the rise of antimicrobial resistance. This association appears to be driven by several factors, including a significant number of prescribers deviating from WHO-recommended prescribing guidelines for all patient groups, including neonates. Furthermore, the increased prescription of antibiotics categorized as “WATCH” by WHO, which are highly susceptible to resistance development, further exacerbates the problems, gaps in dispensing practices; from the research result, health students’ knowledge, attitude, and self-medication practices, inappropriate antibiotics usage, widespread distribution of healthcare-associated infections [30-42].

Ineffective nurses’ communication and behavior towards nosocomial infection, hospital waste disposal and prescribers’ behaviors are all contributing factors to the alarming increase of antimicrobial resistance according to these four results listed here, inadequate implementation of antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) and infection prevention and control (IPC) programs within healthcare facilities creates a significant risk for the emergence of antimicrobial resistance [43-47,71]. A research publication showed an inappropriate proportion of prescribed antibiotics, their distribution, and completeness according to the WHO awareness category, diagnostic investigation before antibiotics prescription, and these are all contributing factors to antimicrobial resistance [13,48]. The findings from five studies consistently demonstrated a critical issue: the absence of essential diagnostic tools, particularly blood culture and susceptibility testing, can significantly compromise results. In some cases, even when these tests are ordered, delays or limitations in laboratory quality can lead to inaccurate results, and anti-microbial resistance biomarkers transmitted through blood transfusion; the presence of mutant alleles of p. falciparum in tested donor blood can reduce the effectiveness of some of these anti-malaria drugs [24,26,32,49,50].

Environmental & community-associated AMR (Self-medication & Health/Food safety):

| Reference no. | Study | Population | Outcome definition | Total (N) | ASM/Non-prescribed cases (k) | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI | Weight (%) |

| 13 | Kretchy et al. | Rural community | Overall prevalence of ASM | 350 | 126 | 36.0 | (34.6-42.8) | 36.4 |

| 24 | Owusu-Ofori et al. | Health students (KNUST) | Self-medication with antibiotics | 280 | 157 | 56.1 | (50.1-62.0) | 33.7 |

| 28 | Aborah et al. | Community (Malaria Patients) | Non-prescribed antimalarials | 392 | 66 | 16.8 | (13.3-21.0) | 29.9 |

| Pooled estimate | Random-effects model | All community/student populations | Overall prevalence of self-medication | 1,022 | 349 | 34.1 | (18.9-53.6) | 100.0 |

Table 4: Pooled analysis – Antimicrobial self-medication (ASM) prevalence

This summary shows that ASM is common in Ghana (pooled estimate: 34.1%). It aggregates data from various studies to quantify the practice, but notes high variability in rates between subgroups, such as students and general community members, which informs the need for targeted public health action.

| Reference no. | Study | Population | Outcome definition | Total samples (N) | Positive contamination (k) | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI | Weight |

| 8 | Agbeko et al. | Fish/pond water | Coliforms contamination | 120 | 95 | 79.2 | (71.8-86.6) | 24.2 |

| 15 | Dela et al | Ready-to-eat Food/Swabs | Multi-drug resistant (MDR) bacteria | 150 | 60 | 40.0 | (32.2-47.8) | 30.3 |

| 16 | Otoo et al. | Environmental (Water/Soil) | Detection of any antibiotic residue | 15 | 14 | 93.3 | (84.7-100.0) | 3.0 |

| 17 | Mtetwa et al. | Waste water | High AMR genes | 15 | 15 | 100.0 | (79.6-100.0) | 3.0 |

| 23 | Paintsil et al. | Poultry Farm Environment | Antibiotic residues in water | 35 | 16 | 45.7 | (29.2-62.2) | 7.1 |

| 26 | Tsekleves et al. | Household dust | MDR resistance | 40 | 28 | 70.0 | (55.8-84.2) | 8.1 |

| 48 | Saba et al. | Hospital surfaces swabs | Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus (MRSA) | 120 | 48 | 40.0 | (30.6-47.8) | 24.2 |

| Pooled estimate | Random-effects model | All sectors | Overall contamination/AMR risk | 495 | 275 | 55.6 | (51.2-59.9) | 100.0 |

Table 5: Pooled analysis – Environmental and food contamination

The combined prevalence of AMR contamination across seven studies (N=495) in Ghana is 55.6% (Precision (95% CI): 51.2%-59.9%). This means over half of all tested samples contain AMR risks (MDR bacteria, AMR genes, or antibiotic residues), confirming widespread environmental contamination that necessitates a “One Health” intervention. Major issues can lead to community-associated AMR, some of which include: unsafe and inappropriate antibiotic usage; several factors contribute to unsafe household antibiotic use: increased utilization without professional guidance, high prevalence of self-medication based on experiences, and limited access to healthcare leading to reliance on unlicensed sellers, as seen in these six articles [51-55]. Inappropriate knowledge and attitude toward antibiotics: three research results showed that sellers’ knowledge gaps contribute to AMR, as evidenced by inappropriate antibiotic selection for the causative organism. Self-reported illnesses necessitating antibiotic use: a tendency to self-medicate with antibiotics on perceived illness, without disclosing symptoms or undergoing diagnostic testing, contributes to the problem of antimicrobial resistance, as seen in the research results by widespread antimicrobial resistance amongst the community, inappropriate wastewater treatment, and inadequate hygiene practices across households [56,67,70]. According to the research studies, poor hygiene and sanitation are linked to the rise of AMR in communities. Treated wastewater showed a higher level of resistant bacteria compared to untreated water, suggesting the potential reintroduction of resistant strains back into the environment [57-59]. Additionally, studies found elevated levels of antibiotic-resistant pathogens in street vendors’ water sources, particularly reused storage water, and non-compliance with the WHO prescription completeness.

Agricultural AMR:

| Reference no. | Study | Population | Outcome definition | Total farms/Cases (N) | Cases of AMU (k) | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI | Weight |

| 4 | Boamah et al. | Selected poultry | Farms reporting use of antibiotics for disease treatment | 400 | 329 | 82.3 | (78.6-86.0) | 26.1 |

| 5 | Adeapena et al. | Kintampo Vet clinic (Case records) | Proportion of animals prescribed antibiotics | 1,416 | 973 | 68.7 | (66.2-71.1) | 39.1 |

| 8 | Agbeko et al. | Fish farms (Aquaculture) | Farms reporting the use of antibiotics for disease | 10 | 8 | 80.0 | (44.4-97.5) | 0.5 |

| 23 | Paintsil et al. | Commercial/domestic poultry | Farms reporting antimicrobial usage | 163 | 127 | 77.9 | (70.8-83.9) | 16.8 |

| 33 | Afakye et al. | Layer farms (Ghana Only) | Self-reported antimicrobial usage | 109 | 71 | 65.1 | (56.3-73.9) | 17.5 |

| Pooled estimate | Random-effects model | Overall agricultural AMU | Overall prevalence of antimicrobial use/prescription | 2,098 | 1,508 | 71.6 | (67.4-75.5) | 100.0 |

Table 6: Pooled analysis – Agricultural AMU

AMU is consistently high and pervasive in Ghana’s animal sectors (pooled: estimate: 71.6%). Nearly three-quarters of all animal health cases or farm operations involve antibiotic use. The highest rates are seen in poultry (82.3%), but the problem spans all key sectors, including veterinary practice and aquaculture. Antibiotic misuse in the agricultural sector was another contributing factor to AMR, these factors obtained from our search include inappropriate antibiotics use in animal farming and production; four articles came out with a result that some agricultural practices for example heavy reliance on antimicrobials by domestic and commercial farmers, often led to misuse due to lack of professional guidance, also informal knowledge sharing among farmers, where they rely on advice from friends or colleagues instead of consulting veterinarians contributed to AMR in Ghana, factors influencing farmers’ choice of antibiotics [60-62]. Knowledge gaps among Ghanaian farmers lead to excessive antibiotic use in livestock, potentially compromising the future effectiveness of these drugs, as seen in a research study [58]. Finally, one result of inappropriate antibiotic prescription practices and issues with the accurate investigation of bacterial contamination in farming water contributed to the rising AMR issue in Ghana [60].

Emerging threats to antibiotic efficacy: A concerning trend of increasing resistance to commonly used antibiotics among commonly isolated pathogens in Ghana, and a specific concern about some WHO-listed antibiotics losing their effectiveness [63]. This study demonstrated a worrying trend of increasing antimicrobial resistance in common pathogens like E. coli, emphasizing the critical need for novel antibiotics due to diminishing treatment options.

| S. No | Study information | Objective | Participants | Study design | Results |

| 1 | Compaore et al.[23] Shai-Osudoku District Hospital and St Andrews Hospital | To explore the determinants of patients’ prescription adherence behaviors as part of the Antimicrobial Resistance Diagnostics Use Accelerator clinical trial | Healthcare providers and patients/caregivers/household decision makers | Qualitative research | Drop in prescription adherence;1. Healthcare workers use very blunt messages to communicate; 2. the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) does not cover all medicines in health facility pharmacies, nor most medicines obtained at private pharmacies/drug shops; 3. Not buying the prescribed medication |

| 2 | Asante et al.[24] Public and private facilities | To guide policy recommendations on antibiotic resistance (ABR), a study was carried out among prescribers to identify gaps in their knowledge of ABR and to document their prescription practices. | Prescribers (Medical doctors, Physician assistants, nurses, Community health officers) | A cross-sectional survey | The knowledge of ABR is high among prescribers. There is, however, a gap in the knowledge and perception of optimal antibiotic prescription practices among health professionals. |

| 3 | Labi et al.[31] Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital (Tertiary care) | To investigate physicians’ knowledge and attitudes towards antibiotic resistance in a tertiary-care hospital setting in Ghana. | Physicians (Senior doctors and Junior doctors) | A cross-sectional respondent-driven survey | Survey showed variable knowledge on the extent and causes of antibiotic resistance, with a high likelihood for underestimating the problem in their own departments or units. |

| 4 | Boamah et al.[58] Selected poultry farms | To investigate the use of essential antibiotics in poultry production in Ghana and to assess factors influencing farmers’ choice of antibiotics for use on their farms. | Poultry farms (Both farmers and pet owners) | Cross-sectional survey | Poultry farmers in the three regions employed several essential antibiotics on their farms for the treatment of infections and prophylaxis purposes. Both internal and external factors influenced farmers’ choice and use of antibiotics on their farms, and if these identified factors are not checked and monitored, they can easily lead to increased antibiotic resistance among the antibiotics used for the treatment of microbial infections and animals. |

| 5 | Adeapena et al.[68] Kintampo North Municipal Veterinary Clinic | To describe antibiotic prescription practices and use in the Kintampo North Municipal Veterinary Clinic in Ghana using routinely collected data | Treatment registers of the Kintampo Municipal Veterinary Clinic | Descriptive study using routinely collected data (retrospective data analysis) | Antibiotics, specifically tetracycline, were commonly used for the treatment of animals in one veterinary clinic in Ghana within the context of poor documentation of antibiotic prescription and use practices. |

| 6 | Amankwa et al.[35] Selected pharmacies in the La Nkwantanang-Madina municipality | To address that gap by assessing factors associated with dispensers’ practices for antimalarials in the La Nkwantanang-Madina municipality | Selected community retail pharmacies | A cross-sectional analytic study | Dispensing practices for anti-malarial are unsatisfactory |

| 7 | Afari-Asiedu et al.[38] Two were selected in the Kintampo North and South Districts | To examine determinants of inappropriate antibiotic use at the community level in rural Ghana | Randomly selected household from the KHDSS database | Mixed Methods | Inappropriate antibiotic use was high and influenced by out-of-pocket payment for healthcare, seeking healthcare outside health centers, pharmacies, and buying antibiotics in installments due to cost. |

| 8 | Agbeko et al.[60] Some selected fish farms in the Central and Western regions of Ghana | To address these issues by obtaining information on farming practices, including the use of antibiotics at fish farms, and to investigate the level of bacterial contamination of water and fishery products. | Farmers with active fish farm production | Cross-sectional study | None of the farm managers admitted using antibiotics, and no record of a major disease outbreak was recorded at the farm throughout the study period. The contamination of fish and pond water with a wide variety of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including coliforms, suggests poor sanitary conditions at the farms. |

| 9 | Owusu-Ofori et al.[37] Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (Tertiary Institution) | To determine health students’ knowledge, attitudes, and self-medication practices on antibiotics and AMR. | First-year health students | Cross-sectional survey | This study has shown that self-medication is common among health students despite their knowledge that antibiotic abuse may lead to resistance. |

| 10 | Do et al.[69] Six low-income and middle-income countries (Ghana, Mozambique, South Africa, Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Thailand) | To use a comparative approach to assess access and use practices across communities in six LMICs in Asia (Bangladesh, Thailand, and Vietnam) and Africa (Mozambique, Ghana, and South Africa) to allow for comparison by national income status and identify key drivers through both qualitative and quantitative measures. | Drug suppliers and consumers, household surveys, and exit interviews among customers who purchased antibiotics | Mixed approach | In Ghana, the main and first approached sources of antibiotics were over-the-counter (OTC) sellers (who are not allowed by regulations to sell antibiotics other than co-trimoxazole) and drug peddlers (street vendors who sell drugs illegally); Unused medicines were shared with others or saved for future use; Purchase of antibiotics without a prescription. |

| 11 | Emmanuella N.[52] KNUST Commercial area in Kumasi (University Community) | To assess the knowledge, attitude, and use of antibiotics among the university community in Ghana. | People in a commercial area | Pilot Study | 78% indicated they purchase their antibiotics from community pharmacies, 15% purchase from the market peddlers and Over the Counter Medicine shops (OTCMS). |

| 12 | Gambrah et al.[26] Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital in Kumasi (Accident & Emergency) | To characterize antibiotic usage in the context of treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection (UTI) received through a Ghanaian Accident & Emergency, which found high rates of improper usage. | Patients | Prospective cohort study | Less than half of Ghanaian adults treated for UTIs had their diagnoses confirmed by urine culture. Few had their treatment appropriately tailored to pathogen susceptibilities. |

| 13 | Kretchy et al.[70] Ga East Municipality | To identify common self-reported illnesses that necessitated ASM, the commonly used antibiotics, and the reasons for ASM. | Adults aged 18 years and above residing in the community for not less than three months. | Community-based cross-sectional survey | The prevalence of ASM is quite high in rural dwellers of Accra, Ghana. There is a higher probability for persons with higher education and those who subscribe to a health insurance policy not to engage in the practice. |

| 14 | Labi et al.[43] Teaching hospitals, regional hospitals, and district hospitals in Ghana | To determine the prevalence and distribution of HAIs in acute care hospitals. | 10 acute care hospitals | Multi-centre Point-Prevalence Survey (PPS) | This study found a prevalence of healthcare-associated infections of 8.2%, which is low compared with findings from other low- and middle-income countries. |

| 15 | Dela et al.[65] Kaneshie Polyclinic, Maamobi General Hospital | To investigate microbial quality and antimicrobial resistance of bacterial species from Ready-to-Eat (RTE) food, water, and vendor palm swab samples. | Food vendors | Cross-sectional study | Although the overall microbiological quality of RTE food was considered safe despite borderline interpretations, some of the individual food items revealed unhygienic and unsafe conditions. |

| 16 | Otoo et al.[46] Sunyani municipality (Environmental Samples) | To investigate the occurrence of two classes of pharmaceuticals (antibiotics and analgesics) in hospital effluents, dumpsite soil and leachates, sachet water, and municipal waterworks samples, and to investigate the risks associated with the presence of these pharmaceuticals in both water and soil samples. | Soil-Soil and sediment samples from dumpsites and municipal waterworks stations; Liquid-Dumpsite leachates, hospital effluents, water samples | Environmental Occurrence and Risk Assessment Study | The findings from this study showed the presence of these pharmaceuticals at concentrations that could impact the ecosystem. Consistent monitoring of environmental levels and pursuing the development and implementation of a suitable remediation program is needed. |

| 17 | Mtetwa et al.[59] Sub-Saharan Africa (Kumasi, Ghana) | To monitor DR-TB in six African countries (Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, Cameroon, and South Africa) and examine the impact of treated wastewater on the spread of TB drug-resistant genes in the environment using Wastewater-Based Epidemiology (WBE) | Wastewater from wastewater treatment plants | Molecular Surveillance Study | Ghana’s wastewater had the highest antibiotic resistance gene levels. |

| 18 | Aninagyei et al.[50] 5 districts (Ashaiman, Accra Metropolis, Ada East, Ga South, and Ga West) | To determine the magnitude of the risk associated with the transmission of these putative anti-malaria drug-resistant biomarkers through blood transfusion. | Blood donors | Cross-sectional Study | This study underscores the high prevalence of malaria in Ghana, which translates into 11.8% of asymptomatic infections in blood donors. For the first time, this study reports the prevalence of putative anti-malaria drug-resistant markers in blood donors. Detection of C580Y Kelch 13 mutation, triple mutation haplotype, YFN, in Pfmdr1 gene and quadruple mutations in the Pfdhfr/Pfdhps genes (Pfdhfr: N51I, C59R, S108N resulting in IRNI haplotype and Pfdhps: A437G, K540E resulting in AGESS haplotype) could contribute to ACT treatment failure and reduced efficacy of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) in transfusion recipients of malaria-infected blood. |

| 19 | Sefah et al.[27] Ho Teaching Hospital | To assess SAP appropriateness among patients undergoing general and gynecological surgery in this hospital and, if needed, seek ways to address concerns raised. | Medical records of patients undergoing surgery over a 5-month duration from January to May 2021 | Retrospective cross-sectional clinical audit | There was poor compliance with SAP prescriptions with local guidelines, mainly due to prolonged duration (>1 day) of antimicrobial prescribing. The most common SAP prescribed was a combination of cefuroxime and metronidazole, which were used mostly for gynecological procedures, with caesarean section being the most prominent indication. |

| 20 | Gnimatin et al.[64] Tamale Zonal Public Health Reference Laboratory (TZPHRL) | To determine the prevalence and resistance profile of bacteria responsible for infections in northern Ghana. To also determine the factors associated with infections caused by multidrug-resistant strains. | Clinical records from patients whose samples have been received for bacterial culture and antibiotic susceptibility testing at the Microbiology section of the TZPHRL from June 2018 to May 2022 | Retrospective cross-sectional design | High resistance rates against the tested antibiotics in the Northern region. Hospitalization was a risk factor for infections by multidrug-resistant organisms. |

| 21 | Hope et al.[28] Bishop Ackon Memorial Christian Eye Centre (BAMCEC) | To document prescribing practices and assess the appropriateness of current antibiotic prescriptions in a specialist eye hospital in Ghana. To also serve as baseline data for determining patient and prescriber characteristics associated with antibiotic prescription patterns. | All patients with new acute conjunctivitis who presented to BAMCEC from 1 January to 31 December 2021 | Cross-sectional Study | Antibiotic prescribing practice in BAMCEC is appropriate and largely follows standard treatment guidelines. However, a relatively large proportion of antibiotics are from the Watch category, and still, almost 30% of the prescriptions were considered inappropriate. |

| 22 | Amponsah et al.[41] Ejisu Municipal, Asante North District, and Kumasi Metropolitan | To provide guidance on the need for pragmatic interventions through AMS and IPC to address and/or contain the high burden of AMR. | A pharmacist (H1), a nurse administrator (H2), and a specialist physician (H3) | Cross-sectional study | All the facilities assessed had AMS capacity and IPC conformity gaps that require strengthening to optimize antimicrobial use (AMU) and successful implementation of IPC protocols. |

| 23 | Paintsil et al.[61] Agogo and Ejisu | To investigate antimicrobial usage in both commercial and domestic poultry farming in two districts in the Ashanti region of Ghana. | 33 commercial farms and 130 domestic farms (household surveys) | Cross-sectional survey | This study revealed high levels of antimicrobial usage in both commercial and domestic poultry farming, with a potential impact on One Health. |

| 24 | Darko et al.[36] Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology | To determine the knowledge, attitudes, and self-medication practices of students in healthcare programs on antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance. | 280 health students | Cross-sectional survey | Self-medication is common among participants despite their knowledge that inappropriate use of antibiotics may lead to resistance. |

| 25 | Owusu et al.[71] Korle Bu Polyclinic or Family Medicine Department | To determine: (1) the proportion of prescribed empirical antibiotics and the distribution of antibiotics across the WHO AWaRE category, (2) the proportion of prescribed empirical antibiotics as recommended in the STGs (dose, frequency, and duration), and (3) the patient and prescriber characteristics associated with not being prescribed empirical antibiotics as recommended in the STGs. | EMR of adults (aged ≥ 18 years) who were diagnosed with uncomplicated UTI (N39.0 of ICD-10) in the outpatient department of the KBPFMD between October 2019 and October 2021. | Cross-sectional audit | The study from a primary health facility of Ghana showed that about nine in ten patients with uncomplicated UTIs were prescribed an empirical antibiotic, of whom 60% were as recommended in the STGs. The major gap was poor adherence in prescribing empirical antibiotics for a recommended duration of time, especially in male patients requiring more than ten days of antibiotics. Taking antibiotics for a shorter period could lead to AMR and recrudescence. |

| 26 | Tsekleves et al.[57] Ga East Municipal Assembly, Adenta Municipal Assembly, and the La Nkwantanang Municipal Assembly. | To develop an understanding of the home as a potential source of infection from AMR bacteria carried by dust by exploring hygiene practices across different household environments in Ghana. | 240 households (survey), 12 households (ethnography), and co-design workshop participants. | Mixed approach | The high prevalence of multidrug resistance observed in this study indicates the need for an antibiotic surveillance program, not only in hospital settings but also in the household environment. This study showed that household dust is just one of many human exposure points for bacteria carrying single or multiple resistances and contributes to the household microbiome. In this study, only opportunist pathogens were found to carry one or more resistances, but still, they pose a threat to human health. The study revealed different nuances in the cleaning patterns and tools across the four socio-economic groups. |

| 27 | Otieku et al.[53] Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital | To evaluate knowledge of AMR, to study how the judgement of health value (HVJ) and economic value (EVJ) affects antibiotic use, and to understand if access to information on AMR implications may influence perceived AMR mitigation strategies. | Adult patients aged 18 years and older seeking outpatient care | Quasi-experimental study | Among study participants, there was a general understanding of when and why to use antibiotics, as well as the implications of AMR. Nonetheless, there was no attributable change in attitude towards antibiotic use among study subjects. Our data showed that both HVJ and EVJ influenced antibiotic use, but the latter was a better predictor among participants when deciding which antibiotic to use. |

| 28 | Aborah et al.[56] Bolgatanga Municipality | To investigate the use of non-prescribed anti-malarial drugs for the treatment of malaria in the Bolgatanga Municipality of northern Ghana. | 392 adults and children with malaria in the last four weeks prior to the study. | Cross-sectional survey | The use of non-prescribed anti-malarial drugs among patients is influenced by respondents’ knowledge, peer influence, and perceived severity of symptoms. The high use of non-prescribed anti-malarial drugs in the municipality, most of which were monotherapy, has implications for the current malaria treatment policy. |

| 29 | Opoku et al.[29] 6 health facilities (Police, Pentecost Hospital, Ga South Municipal and La General Hospitals, Kekele Polyclinic, and Ngleshie Amanfrom Health Centre) | To determine the factors associated with antibiotic prescription to febrile outpatients who seek care in health facilities within the Greater Accra region of Ghana. | Medical records of 2519 febrile outpatients, Quantitative research | Secondary data analysis (cross-sectional audit) | Prescription of antibiotics to febrile outpatients was high. |

| 30 | Garcia-Vello et al.[30] Tamale Teaching Hospital | To assess the use of antibiotics in Tamale Teaching Hospital and provide information that could be used to develop an antibiotic stewardship program in the hospital. | 617 patients’ records | Cross-sectional study | The study revealed a high burden of antibiotic misuse in the Tamale Teaching Hospital. |

| 31 | Labi et al.[31] regional hospitals, teaching hospitals, and district hospitals in Ghana | To describe antibiotic prescribing patterns among hospitalized children and adolescents in Ghana using data from a multicenter point prevalence survey conducted between September and December 2016 | patients’ folders and charts > 18years | Quantitative research | The study shows high use of antibiotics among pediatric inpatients in Ghana. It also highlights key differences in antibiotic use among neonates and other pediatric populations. |

| 32 | Afari-Asiedu et al.[38] Kintampo North, South Districts | To further explore inappropriate antibiotic use and confusing antibiotics with other medicines that are in capsules, tablets, and antibiotics with similar colors at the community level in Ghana. | Health professionals and dispensers who prescribe and dispense antibiotics in the study area. | Explorative Study (Qualitative research) | Inappropriate antibiotic use was influenced by a general lack of knowledge on antibiotics and the identification of antibiotics by the colors of their capsules, which leads to confusion and could lead to inappropriate antibiotic use. |

| 33 | Afakye et al.[65] Dormaa Central Municipal | To assess how animal health-seeking practices on layer farms in Ghana and Kenya impact self-reported antimicrobial usage, engagement in prudent administration and withdrawal practices, and perceptions of AMR. | 109-layer farmers | Mixed approach (Cross-sectional survey) | Animal Health Service Providers (AHSP) seeking frequency was largely not associated with prudent use practices. |

| 34 | Labi et al.[40] Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital | To determine the prevalence and indications for use of antibiotics at the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana. | 677 inpatients | Point Prevalence Survey (PPS) (Cross-sectional chart) | This study indicated a high prevalence of antibiotic use among inpatients at the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital. Metronidazole was the most used antibiotic, mainly for surgical prophylaxis. |

| 35 | Donkor et al.[14] Bomso Clinic and St. Dominic Hospital | To determine the prevalence of prior antibiotic use through a cross-sectional survey of patients undergoing laboratory tests at two health facilities in Ghana. | 261 patients visiting the medical laboratory | Cross-sectional survey combined with urine bioassay | This study has shown that nearly a third of patients had used antibiotics prior to their bacteriological laboratory tests. It has also been shown that prior antibiotic use (as determined by urine antimicrobial activity) increases the likelihood of obtaining culture-negative results and thus influences the outcome of laboratory results. |

| 36 | Labi et al.[44] Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital | To investigate physicians’ knowledge and attitudes towards antibiotic resistance in a tertiary-care hospital setting in Ghana. | 159 Physicians of all levels of expertise at the Departments of Medicine, Surgery, Pediatrics, and Obstetrics and Gynecology | Retrospective Clinical Audit (cross-sectional) | In summary, respondents from this survey showed variable knowledge on the extent and causes of antibiotic resistance, with a high likelihood for underestimating the problem in their own departments or units. |

| 37 | Afari-Asiedu et al.[56] Kintampo North, South Districts | To provide insight into the differences between regulatory and community demands on the sale of antibiotics, and to explore how these differences in demand could be resolved to facilitate safe and appropriate use of antibiotics in rural Ghana. | 16 among antibiotic suppliers, predominantly LCS, and 16 among community members | Mixed-Method/Explorative study (IDIs and FGDs) | Generally, antibiotic suppliers were aware that regulations prevent Licensed Chemical Sellers (LCS from selling antibiotics except Cotrimoxazole. However, LCS sells all types of antibiotics because of community demand, economic motivations of LCS, and the poor implementation of regulations that are intended to prevent them from selling these medications. |

| 38 | Boakye-Yiadom et al.[49] Ho Teaching Hospital | To describe blood CDST requests by clinicians and the quality of CDST processes for the diagnosis of BSI among patients admitted to HTH from 2019 to 2021. | All inpatients admitted to HTH from January 2019 to December 2021 with at least one clinical diagnosis or suspicion of a BSI. | Cross-Sectional Study | This study found low clinician requests for blood CDST for inpatients with suspected BSI. Furthermore, the clinical utility of the test for the few for whom it was requested was limited by a significant delay in the decision to request and some laboratory quality issues. |

| 39 | Omenako et al.[32] The Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital | To describe: (a) antimicrobial prescription patterns and compliance with recommendations of the national standard treatment guidelines (STG) for the management of sepsis, (b) blood culture positivity rate and antimicrobial sensitivity pattern of bacterial isolates, and (c) treatment outcomes at the time of hospital discharge. | Medical records of neonates (<28 days of age) admitted with suspected sepsis. | Cross-Sectional Study (retrospective medical and laboratory records review) | In this cross-sectional study, in neonates admitted with suspected sepsis in a teaching hospital in Ghana between January and December 2021, we found a high prevalence of antimicrobial use, which was not compliant with national STGs |

| 40 | Darkwah et al.[34] Ghana Police Hospital | To evaluate the prescribing pattern of antibiotics at the Ghana Police Hospital using the National Standard Treatment Guidelines (STG) and the World Health Organization (WHO) prescribing indicators | Prescriptions of outpatients and inpatients’ folders within clinical areas and at the hospital pharmacies. | A cross-sectional descriptive study | Study revealed that the level of appropriateness for prescribing indicators assessed was relatively high, and the majority of prescribed antibiotics were from the “access” and “watch” group. |

| 41 | Kukula et al.[67] Shai-Osudoku District | To explore behavioral factors relating to the prescription and communication of prescription-adherence messages for patients with acute febrile illness, from which to develop a training-and-communication (T&C) intervention to be delivered as part of a clinical trial. | 39 health workers and 66 community members | Nested Qualitative research | Our study revealed that prescribers/dispensers communicate with patients depending on the patient’s educational level, existing disease condition, workload, religion, medicine availability, and language. Community members’ adherence to a prescription is determined by the availability of money, affordability of medicine, severity of the condition, and work schedule (which translates to forgetfulness). |

| 42 | Amponsah et al.[48] University Hospital, KNUST (Outpatient Prescribing) | To assess: (a) demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who received antibiotics, (b) the monthly trend of antibiotic prescribing per WHO AWaRe classification, and (c) completeness of antibiotic prescriptions. | Prescriptions of all patients treated at the OPD of the University Hospital between January and December 2021. | Cross-Sectional Study (retrospective EMR review) | There was high antibiotic usage in the hospital when compared to WHO standards. The use of antibiotics from the Watch group was widespread. The antibiotic prescription parameters were well-documented. |

| 43 | Amponsah et al.[41] University Hospital Service, KNUST, Agogo Presbyterian Hospital, Ejisu Government Hospital | To assess the prevalence of antibiotic use, the pattern of commonly used antibiotics, and patient factors that may be associated with the increased use of antibiotics in the study hospitals. | Hospital records of inpatients | Point Prevalence Survey (PPS) using WHO methodology | The prevalence of antibiotic consumption in the hospitals was lower than that reported in similar studies in Ghana, but high relative to some reports from high-income countries. |

| 44 | Vicar et al.[55] Dungu-Asawaba and Moshie Zongo (Household use) | To assess the relationship between knowledge, attitude, and practices of antibiotic use among households in urban informal settlements in the Tamale metropolis of Ghana. | 660 Households | A prospective cross-sectional survey | This study exposes the drivers of inappropriate use of antibiotics at the household level, particularly in urban informal settlements. |

| 45 | Amponsah et al.[48] The University Hospital, KNUST (Prescribing Indicators) | To assess adherence to the WHO/INRUD rational use of medicines prescribing indicators at the outpatient department of University Hospital, KNUST, in the Ashanti region of Ghana in 2021. | Electronic data from outpatient medical records | A cross-sectional study (retrospective EMR review) | The hospital practices of Random Use of Medicines (RUM) were mostly not in accordance with the WHO/INRUD standards. However, the use of injections seemed to be compliant with the standards. |

| 46 | Dodoo et al.[63] Ho Teaching Hospital | To determine the antimicrobial prescription pattern in the Ho Teaching Hospital on two separate occasions in a total of 14 wards in the hospital, including dedicated wards for pediatrics and neonates. | Patients’ folders and treatment charts | Global Point Prevalence Survey (PPS) – Two cross-sectional surveys | The indicators evaluated in the HTH showed that the facility has several positive practices regarding antimicrobial stewardship. This was evident during both surveys, as reasons for antimicrobial prescriptions were documented in almost 70% of the cases. In addition, there were stop or review dates documented in over 90% of the instances where antimicrobials were prescribed for inpatients. |

| 47 | Sefah et al.[42] The University of Health and Allied Sciences | To assess their knowledge on antibiotic use, AMR, and AMS | Student population of 252, comprising 30 pharmacy students, 73 medical students, 84 nursing students, and 65 physician assistant students | A cross-sectional survey | There are disparities in the overall level of knowledge of antibiotics, AMR, and ASPs among the different healthcare students at this University in Ghana. |

| 48 | Saba et al.[44] Tamale Teaching Hospital, Tamale Central Hospital, and Tamale West Hospital | To determine the prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility of S. aureus and Methicillin Resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in the environments of three hospitals in Ghana. | 120 swab samples form door handles, stair railings and other points of contact | Environmental Cross-Sectional Study (culture and disk diffusion AST) | The high multi-drug resistance of MRSA in hospital environments in Ghana reinforces the need for the effective and routine cleaning of door handles in hospitals. Further investigation is required to understand whether S. aureus from door handles the possible causes of nosocomial diseases in the hospitals. |

| 49 | Salu et al.[45] Hohoe Municipality |

To assess nurses’ knowledge on nosocomial infection (NCI) preventive measures and its associated factors in Ghana. | Nurses working in the Hohoe Municipality | A cross-sectional study design | A significant proportion of nurses in Ghana lack knowledge of NCI prevention. |

| 50 | Dodoo et al.[66] Ho Teaching Hospital (Antibiogram Development) |

To develop a local antibiogram for the Ho Teaching Hospital. | Routinely collected data on all isolates reported on the LHIMS from January 2021 to December 2021 | A retrospective cross-sectional study | The study reveals the resistance patterns of E. coli and Klebsiella spp. to some antibiotics on the WHO ‘Watch’ and ‘Reserve’ lists. |

Table 7: Data Extraction sheet

Discussion

Ghana confronts a relentless foe: the escalating threat of AMR. This chronic challenge demands immediate action. AMR erodes the bedrock of modern medicine, rendering antibiotics ineffective against bacterial infections. The consequences are dire: prolonged illnesses, soaring costs, and even mortality. To combat this menace, we must dissect the intricate web fueling AMR in Ghana, encompassing healthcare practices, patient behavior, and socio-economic realities. This study sheds light on this complex public health threat. Unravelling these factors is crucial in crafting effective interventions and safeguarding antibiotic efficacy in Ghanaian healthcare.

Healthcare-associated AMR: This systematic review underscores the critical role healthcare workers and healthcare facilities play in the rise of AMR in Ghana. Their practices and limitations emerge as a significant factor contributing to the problem. Patient adherence to antibiotic regimens is a complex issue influenced by various factors, including potential shortcomings in healthcare workers’ communication of essential prescription instructions. Healthcare workers’ (HCWs) communication tactics focused on severity and fear may be linked to lower patient adherence to antibiotic regimens. An emphasis on illness severity, fear-induction, and leveraging lab results to highlight seriousness might be associated with decreased adherence rates, as evidenced by a potential drop from 90.3% to 82.9%.[23]

Prescribers’ knowledge and behavior are also recognized as significant contributors to the rise of AMR. This study showed that prescribers’ knowledge of AMR exhibited significant variability. While senior prescribers demonstrated a high level of understanding regarding the extent and causes of AMR, junior prescribers displayed a tendency to underestimate the problem within their departments.[24,25] Another particularly concerning element is the presence of inconsistency and dissonance within antimicrobial prescribing practices. Hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) represent a significant contributor to the rise of AMR within the healthcare settings in Ghana. While the overall prevalence of HAIs remained relatively low in Ghana, a cause for concern emerged in the high levels of environmental contamination with Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) on hospital door handles, particularly in areas with high surgical caseloads. Similar concerns extend to water sources. The presence of antibiotic residues in hospital effluents and leachate from dumpsites raises concerns about potential environmental contamination. Notably, Ciprofloxacin was detected at alarmingly high concentrations, exceeding levels known to contribute to the development of antimicrobial resistance. Furthermore, the isolated strains of S. aureus and MRSA exhibited concerning resistance patterns, with some isolates demonstrating resistance to a broad spectrum of antibiotics, including a particularly alarming resistance to pan-resistant MRSA.[43,44,46] Adding to the complexities of addressing AMR in Ghana, a separate study revealed a knowledge gap regarding nosocomial (Hospital-acquired) infection (NCI) prevention among a significant portion of nurses. While this finding may not necessarily generalize to all healthcare workers, it underscores a potential vulnerability within the Ghanaian healthcare system. Inadequate knowledge of NCI prevention practices could facilitate the spread of antimicrobial-resistant pathogens within hospitals, ultimately contributing to the rise of AMR.[45]

While some studies indicate instances of guideline adherence for antimicrobial prescribing, a concerning trend emerges.[28,33] Overall, antibiotic use by healthcare providers significantly exceeds recommendations established by both local and international (WHO) guidelines.[27,30,34,48] This concerning pattern extends even to pediatric populations, particularly neonates.[31,32] Furthermore, research suggests a prevalence of prescriptions within the “Watch” category, a class of antibiotics associated with a higher risk of resistance development.[33,34] Beyond prescription practices, gaps in the AMS-IPC infrastructure fuel AMR in Ghana. Weaknesses in both AMS capacity and IPC conformity within Ghanaian healthcare facilities represent significant vulnerabilities that contribute to the rise of AMR.[47]

The widespread practice of prescribing antibiotics without proper diagnostic investigation is another critical challenge facing the fight against AMR in Ghana. This concerning trend extends to both inpatients and outpatients. Healthcare providers, aware of the potential viral nature of some infections and the limited benefit of antibiotics in such cases, nonetheless choose to prescribe these medications. This phenomenon can be attributed, in part, to the dearth of facilities equipped with culture and sensitivity testing capabilities, a crucial tool for identifying the causative agent of infection. Research corroborates this, revealing that less than half of both adult UTI patients and neonates with suspected sepsis receive confirmatory testing. Furthermore, even when such testing is requested, delays and potential laboratory quality issues can compromise its clinical utility.[24,26,29,32,49,64] This fight extends beyond prescribing practices to the realm of community pharmacy dispensing. This research identified a troubling trend: patients receiving inappropriate medication information during the dispensing process. Paradoxically, dispensers with extensive experience (over 10 years) were less likely to dispense the lifesaving Antimalarial combination therapy (ACT) medications appropriately. Conversely, pharmacy interns exhibited a higher level of adherence to proper ACT dispensing protocols.[35] The battle against AMR in Ghana takes an unexpected adversary with the emergence of a potential hidden reservoir: asymptomatic malaria parasites in donated blood. A recent study revealed a concerning prevalence: 11.8% of blood donors in Ghana tested positive for malaria despite exhibiting no symptoms. Further analysis revealed a troubling element-the presence of mutant alleles in key genes of P. falciparum, the malaria parasite, within these infected donors. These mutations could potentially reduce the efficacy of standard antimalarial therapies, raising the specter of AMR in transfusion-transmitted malaria cases.[50]

Community-associated AMR: AMR presents a formidable challenge to global healthcare, jeopardizing the effectiveness of antibiotics in treating common infections. This study also shows the alarming rise of community-acquired AMR in Ghana. It delves into the factors driving this public health threat, aiming to identify effective interventions to safeguard the community. There was a concerning prevalence of antibiotic use in households, with a significant portion coming from unlicensed vendors. This highlights the issue of self-medication with antibiotics, often driven by factors like past experiences, healthcare access limitations, and cost considerations. Another study also investigates antibiotic self-medication (ASM) in Ghana. It reveals a high prevalence of ASM in urban informal settlements, with concerning aspects like using leftover antibiotics and acquiring them from unlicensed sellers. Another study also suggests factors influencing ASM, such as limited knowledge, economic hardship, and difficulties getting prescriptions at hospitals. Additionally, the presence of unregulated sellers who dispense antibiotics undermines efforts to promote responsible antibiotic use.[52-55]

This study further explores knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) related to AMR in Ghana. Despite some general knowledge about antimicrobials and resistance in the community, there are concerning gaps. The study identifies a knowledge gap among some sellers of medications, potentially leading to misuse. Additionally, misconceptions and economic factors significantly influence how people use antimicrobials. These factors contribute to practices like using ineffective medications (using antibiotics for a viral infection) or stopping prescribed treatments prematurely.[56]

This study further examines the relationship between hygiene and sanitation practices in the community and the concerning rise of AMR. The findings provide evidence that deficiencies in these practices contribute significantly to the environmental spread of AMR. Wastewater analysis revealed the presence of antibiotic-resistance genes (ARGs) for various antibiotics, including those used for first-line and second-line tuberculosis (TB) treatment. This concerning result highlights the potential for the dissemination of AMR within the community. Furthermore, the study identified that the concentration of ARTs in treated wastewater was sometimes higher than in untreated wastewater. This suggests that existing wastewater treatment plants may not be entirely effective in removing these genes from the effluent, potentially creating a reservoir for the spread of resistant bacteria back into the community. Household cleaning practices were also investigated. While participants reported frequent cleaning routines, significant knowledge gaps were identified regarding the connection between dust and germs and the proper use of disinfectants. This suggests that current cleaning practices may be inadequate for effectively eliminating bacteria, potentially including those harboring antibiotic resistance. Further evidence for the link between hygiene and AMR was identified in the analysis of environmental samples from Ghana. The presence of antibiotics in concerning concentrations within street vendors’ water sources, particularly reused storage water, suggests potential fecal contamination and the transmission of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. In conclusion, deficiencies at both the community level, such as wastewater treatment inefficiencies, and the household level, through inadequate cleaning practices, contribute to the environmental spread of antibiotic-resistance genes.[46,57,59,65]

Agriculturally associated AMR: This study also unveils that the Ghanaian agricultural system is a potential reservoir for AMR transmission. Economic constraints lead heavily to antimicrobials, which are often misused. Domestic farmers, while using less overall, exhibit concerning trends: excessive daily use, unverified advice (from friends and other farmers), and readily available pharmacy purchases, bypassing veterinary services. Limited veterinary outreach and herbal remedy use alongside antimicrobials further exacerbate AMR risks. Inadequate communication with agro-vets and unhygienic environments suggest a link between antibiotic use and poor farm sanitation. Interestingly, a study showed that farmers reported no antibiotic use but displayed high bacterial contamination and resistance to specific antibiotics.[58,60-62] These findings highlight the urgent need to address farmers. Education, veterinary services, and antimicrobial use regulations to mitigate AMR within Ghana’s agricultural sector and safeguard public health.

This study also identified incomplete antibiotic courses and disregard for withdrawal periods on livestock farms in Ghana. These practices likely stem from a lack of veterinary oversight or farmer education. Incomplete courses expose microbes to sub-lethal antibiotic doses, promoting the development of resistance. Skipping withdrawal periods allows antibiotic residues to persist in animal products destined for human consumption.[58] These findings highlight the need for interventions that improve farmer knowledge and ensure proper veterinary guidance on antibiotic use in livestock.

Emerging threats to antibiotic efficacy: The specter of antibiotic resistance looms large in Ghana. While responsible use is crucial, our current arsenal is weakening. New antibiotics are urgently needed to combat this growing threat. A study at a healthcare referral facility in Ghana identified a worrying trend of antibiotic resistance among common bacterial pathogens. E. coli, Pseudomonas spp., and Klebsiella spp. were frequently isolated from patients with urinary tract infections and ear infections. These pathogens exhibited concerning resistance levels, particularly to beta-lactam antibiotics like ampicillin, piperacillin, ceftriaxone, and ceftazidime. The emergence of resistance to even last-resort antibiotics like colistin is particularly alarming.[63] These findings highlight the urgent need for the development of new antibiotics. The current arsenal of antibiotics is becoming increasingly ineffective in Ghana, leaving healthcare providers with limited options for treating serious infections. Investing in research and development of novel antibiotics is essential to combat the growing antimicrobial resistance.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this systematic review identified a multifactorial challenge driving AMR in Ghana. Inappropriate antibiotic use, knowledge gaps, and sanitation deficiencies across healthcare facilities, communities, and the agricultural sector all contribute significantly to the rise of AMR. Notably, most of the research originated from referral hospitals within prominent Ghanaian cities. Further research is necessary in other regions, especially newly created regions and rural areas, to obtain a more comprehensive national understanding of AMR in Ghana. Urgent interventions are required to address these issues and preserve the efficacy of antibiotics in Ghana. These include promoting responsible prescribing practices within healthcare facilities, educating communities on proper antibiotic use and hygiene practices, strengthening veterinary oversight in the agricultural sector, and investing in research and development of novel antibiotics. By implementing a multi-pronged approach across all Ghanaian regions, the nation can combat AMR and safeguard public health for future generations.

References

- InformedHealth.Org. In Brief: What Are Microbes? Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2022.

In Brief: What Are Microbes? - Nemours Kidshealth. Germs: Bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa.

Germs: Bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa - Merriam Webster. Definition of antimicrobial.

Definition of ANTIMICROBIAL - Microbiology Society. Microbes and the human body.

Microbes and the human body - Nankervis H, Thomas KS, Delamere FM, Barbarot S, Rogers NK, Williams HC. Antimicrobials Including Antibiotics, Antiseptics and Antifungal Agents. NIHR Journals Library; 2016.

Antimicrobials Including Antibiotics, Antiseptics and Antifungal Agents - World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance. 2023.

Antimicrobial resistance - CDC. About Antimicrobial Resistance. 2025.

About Antimicrobial Resistance - World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance. 2024.

Antimicrobial resistance - Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629-655. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Uddin TM, Chakraborty AJ, Khusro A, et al. Antibiotic resistance in microbes: History, mechanisms, therapeutic strategies and future prospects. J Infect Public Health. 2021;14(12):1750-1766. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2021.10.020

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR). 2025.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) - African health ministers mobilize against dangerous threat of antimicrobial resistance. WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Accessed September 11, 2025.

African health ministers mobilize against dangerous threat of antimicrobial resistance - Amponsah OKO, Courtenay A, Ayisi-Boateng NK, et al. Assessing the impact of antimicrobial stewardship implementation at a district hospital in Ghana using a health partnership model. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2023;5(4):dlad084. doi:10.1093/jacamr/dlad084

Crossref | Google Scholar - Donkor ES, Muhsen K, Johnson SAM, et al. Multicenter Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance among Gram-Negative Bacteria Isolated from Bloodstream Infections in Ghana. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023;12(2):255. doi:10.3390/antibiotics12020255

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Opoku R, Dwumfour-Asare B, Agrey-Bluwey L, et al. Prevalence of self-medication in Ghana: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2023;13(3):e064627. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2022-064627

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Jimah T, Ogunseitan O. National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance: stakeholder analysis of implementation in Ghana. Journal of Global Health Reports. 2020;4:e2020067. doi:10.29392/001c.13695

Crossref | Google Scholar - Ghana 2021 Population and Housing Census. Population Projection 2021 – 2050. Accessed September 11, 2025.

Population Projection 2021 – 2050 - Ofori FNK. The Socio-economic challenges and opportunities of Ghana’s coastal communities: The cases of Ada and Keta. Reg Mag. 2021. doi:10.1080/13673882.2021.00001101

Crossref - Kwabena N. Map of Ghana showing the 16 regions. Adinkra Symbols & Meanings. 15 September 2020. Accessed September 11, 2025.

Map of Ghana showing the 16 regions - Adua E, Frimpong K, Li X, Wang W. Emerging issues in public health: a perspective on Ghana’s healthcare expenditure, policies and outcomes. EPMA J. 2017;8(3):197-206. Published 2017 Aug 18. doi:10.1007/s13167-017-0109-3

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - UNICEF Ghana. Ghana Poverty and Inequality Analysis. Accra, Ghana: UNICEF; 2016.

Ghana Poverty and Inequality Analysis - Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Compaoré A, Ekusai-Sebatta D, Kaawa-Mafigiri D, et al. Viewpoint: Antimicrobial Resistance Diagnostics Use Accelerator: Qualitative Research on Adherence to Prescriptions. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;77(Suppl 2):S206-S210. doi:10.1093/cid/ciad323

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Asante KP, Boamah EA, Abdulai MA, et al. Knowledge of antibiotic resistance and antibiotic prescription practices among prescribers in the Brong Ahafo Region of Ghana; a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):422. Published 2017 Jun 20. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2365-2

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Labi AK, Obeng-Nkrumah N, Bjerrum S, et al. Physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions concerning antibiotic resistance: a survey in a Ghanaian tertiary care hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:126. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-2899-y

Crossref | Google Scholar - Gambrah E, Owusu-Ofori A, Biney E, Oppong C, Coffin SE. Diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract infections in hospitalized adults in Ghana: The role of the clinical microbiology laboratory in improving antimicrobial stewardship. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:497-500. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.068

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Sefah IA, Denoo EY, Bangalee V, Kurdi A, Sneddon J, Godman B. Appropriateness of surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis in a teaching hospital in Ghana: findings and implications. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2022;4(5):dlac102. Published 2022 Oct 10. doi:10.1093/jacamr/dlac102

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Hope PKF, Lynen L, Mensah B, et al. Appropriateness of Antibiotic Prescribing for Acute Conjunctivitis: A Cross-Sectional Study at a Specialist Eye Hospital in Ghana, 2021. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(18):11723. Published 2022 Sep 17. doi:10.3390/ijerph191811723

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Opoku MM, Bonful HA, Koram KA. Antibiotic prescription for febrile outpatients: a health facility-based secondary data analysis for the Greater Accra region of Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):978. Published 2020 Oct 27. doi:10.1186/s12913-020-05771-9

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Garcia-Vello P, Brobbey F, Gonzalez-Zorn B, Setsoafia Saba CK. A cross-sectional study on antibiotic prescription in a teaching hospital in Ghana. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35:12. Published 2020 Jan 15. doi:10.11604/pamj.2020.35.12.18324

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Labi AK, Obeng-Nkrumah N, Sunkwa-Mills G, et al. Antibiotic prescribing in paediatric inpatients in Ghana: a multi-centre point prevalence survey. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):391. Published 2018 Dec 20. doi:10.1186/s12887-018-1367-5

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Omenako KA, Enimil A, Marfo AFA, et al. Pattern of Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Antimicrobial Treatment of Neonates Admitted with Suspected Sepsis in a Teaching Hospital in Ghana, 2021. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19):12968. Published 2022 Oct 10. doi:10.3390/ijerph191912968

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Darkwah TO, Afriyie DK, Sneddon J, et al. Assessment of prescribing patterns of antibiotics using National Treatment Guidelines and World Health Organization prescribing indicators at the Ghana Police Hospital: a pilot study. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;39:222. Published 2021 Aug 2. doi:10.11604/pamj.2021.39.222.29569

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Amponsah OKO, Nagaraja SB, Ayisi-Boateng NK, et al. High Levels of Outpatient Antibiotic Prescription at a District Hospital in Ghana: Results of a Cross Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(16):10286. Published 2022 Aug 18. doi:10.3390/ijerph191610286

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Amankwa CE, Bonful HA, Agyabeng K, Nortey PA. Dispensing practices for anti-malarials in the La Nkwantanang-Madina municipality, Greater Accra, Ghana: a cross-sectional study. Malar J. 2019;18(1):260. Published 2019 Jul 30. doi:10.1186/s12936-019-2897-5

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Darko E, Owusu-Ofori A. Antimicrobial resistance and self-medication: A survey among first-year health students at a tertiary institution in Ghana. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;101:43. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.145

Crossref | Google Scholar - Owusu-Ofori AK, Darko E, Danquah CA, Agyarko-Poku T, Buabeng KO. Self-Medication and Antimicrobial Resistance: A Survey of Students Studying Healthcare Programmes at a Tertiary Institution in Ghana. Front Public Health. 2021;9:706290. Published 2021 Oct 8. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.706290

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Afari-Asiedu S, Hulscher M, Abdulai MA, et al. Every medicine is medicine; exploring inappropriate antibiotic use at the community level in rural Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1103. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09204-4

Crossref | Google Scholar - Labi AK, Obeng-Nkrumah N, Nartey ET, et al. Antibiotic use in a tertiary healthcare facility in Ghana: a point prevalence survey. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7:15. Published 2018 Jan 26. doi:10.1186/s13756-018-0299-z