Author Affiliations

Abstract

Background: Adolescent motherhood poses significant public health challenges, marked by adverse maternal health outcomes. Adolescent mothers face a higher risk of pregnancy complications and death than their older counterparts, yet they exhibit improper health-seeking behavior in the uptake of maternal health services (MHS). Understanding the factors affecting health-seeking behavior in the uptake of MHS among adolescent mothers remains limited and inadequately understood. This study aims to identify those factors affecting health-seeking behavior in the uptake of maternal health services among adolescent mothers in Nigeria.

Methodology: This study employed a literature review approach, drawing from databases such as Elsevier, PubMed, Google, and Google Scholar, utilizing the socioecological model as an analytical framework to comprehensively explore the factors affecting health-seeking behaviour in the uptake of maternal health services among adolescent mothers in Nigeria. The geographical focus extends to West African countries with similar contexts.

Findings: The findings reveal multilevel factors contributing to flawed health-seeking behavior and low MHS utilization among adolescent mothers, encompassing education disparities, poverty, limited autonomy, weak support systems, stigmatization, judgmental healthcare attitudes, and accessibility barriers.

Conclusion and Health Implications: The study underscores the imperative of integrating adolescent-friendly MHS within Nigeria’s maternal health framework to address specific needs and calls for tailored policies and interventions targeting adolescent mothers, particularly in underserved areas, to bridge existing disparities in maternal health service access and further enhance health outcomes.

Keywords

Antenatal care, Postnatal care, Adolescent mothers, Health-seeking behavior, Nigeria.

Introduction

Adolescent pregnancies and childbirths are serious social and public health crises that have negative impacts on maternal health.[1-8] Young mothers are more likely than older women aged 20 to 24 to experience pregnancy problems such as systemic infections, puerperal endometritis, eclampsia, preterm delivery, perinatal mortality, low birth weight, and death.[1-3,8-14] Compared to women aged 20 to 24, they have a 1.5 times higher risk of dying while giving birth.[15-19] Additionally, due to their higher risk of illness, newborns born to them are more likely to pass away before their first birthday.[20-22]

Per World Bank data, Nigeria had an extremely high rate of maternal mortality of roughly 917 per 100,000 live births in 2017.[23-30] In the Fragile State Index of 2017, Nigeria was placed fourth among the 15 African nations on “high alert” for maternal deaths.[31] The proportion of adolescent mothers in Nigeria appears to be rising, and it is worth noting that adolescents’ voices are presently under-represented, despite the pregnancy-related risk they face.[11,32-36] According to the 2018 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS), the rate of teenage births is 106 births per 1000 women, in the northern area of Nigeria, where the average age of marriage and first encounter is about 16 years, having the highest rate. Furthermore, the study reveals that 19% of adolescents have begun to procreate, 14% already have children, and 4% are expecting their first child.[35,37] To achieve the sustainable development goal (SDG) of lowering the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) to 70 per 100,000 deaths per live delivery by 2030, it is crucial and necessary to focus on this age group. Research shows that with proper use of maternal health services, these pregnancy-related complications and fatalities can be avoided.[16,38,39] Women who received skilled maternal health services had better pregnancies and did better in the postpartum period than those who did not.[40-42] However, there have been reports of adolescent moms engaging in poor health-seeking behavior.[12,33,41-44] Even in locations where maternal health services are freely available and affordable, this age group exhibits poor maternal health-seeking behavior despite the elevated risk they incur.[24,32,45]

What factors influence adolescent mother’ usage of maternal health services and their behavior concerning seeking out health care in Nigeria? This literature review aims to pinpoint factors influencing adolescent mothers’ health-seeking behavior in Nigeria. The findings will aid in the formulation of policies by policymakers and other pertinent parties to promote the use of maternal health care. Designing adolescent-friendly maternity care would also help to increase the adoption of maternal health treatments, thereby helping to reduce the incidence of maternal death in Nigeria overall.[29,46]

Methodology

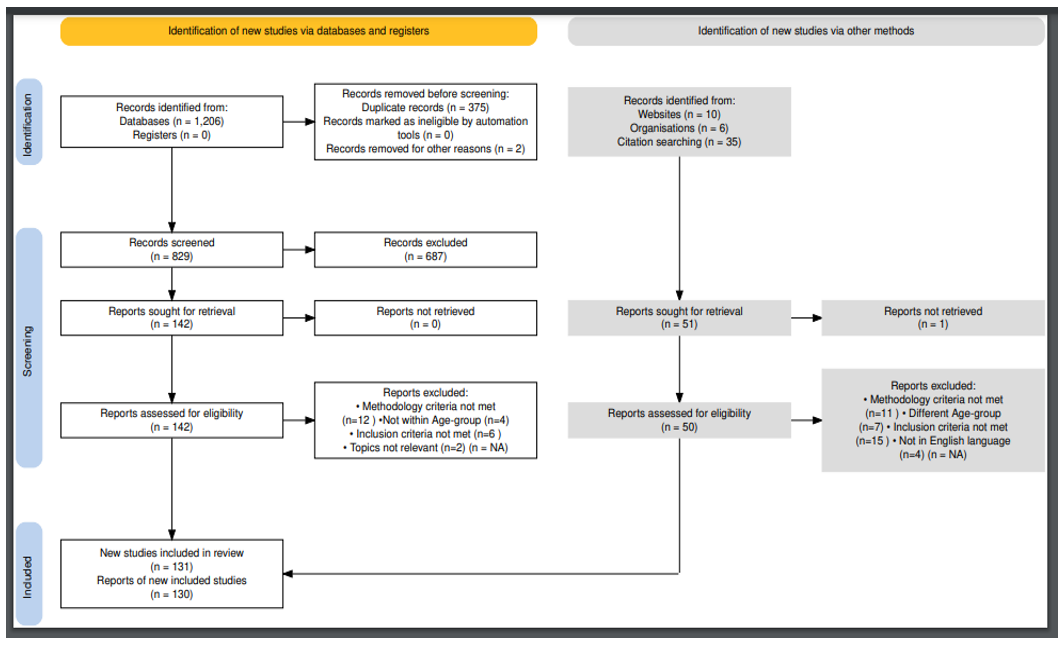

The study employed a narrative review of the literature. We extracted articles unsystematically from the National Library of Medicine (PubMed), Research Gate, Science Direct, and Google Scholar, released between 2013 and 2023, using keywords specific to each section. We used the “OR” and “AND” Boolean combinations iteratively to search for relevant articles. The keywords and search terms used during the search included but were not limited to: “Health seeking behavior”, “Adolescent mothers”, “maternal mortality”, “maternal health services”, “Adolescent health services”, “reproductive health policies”, “decision-making autonomy”, Individual factors”, Interpersonal factors”, “Cultural beliefs”, “Religious beliefs”, “traditional factors”, “stigmatization”, “health worker attitudes”. Due to a dearth of information specifically tailored to adolescent mothers, pertinent studies using qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods research approaches on women of reproductive age (15-49) were included. The World Health Organization (WHO), Federal Ministry of Health, NDHS, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), National Health Management Information System (NHMIS), World Bank, and United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) also provided pertinent data. NDHS is a country-specific survey, was included because it offers accurate and age-specific estimates of associated health variables among adolescents (15-19). Pertinent articles from Africa and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) with comparable features were also included. On combining the keywords and search terms differentially, we retrieved a total of 377 articles. However, we disregarded 246 articles after reading the abstract and taking into account the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Synthesis of results:

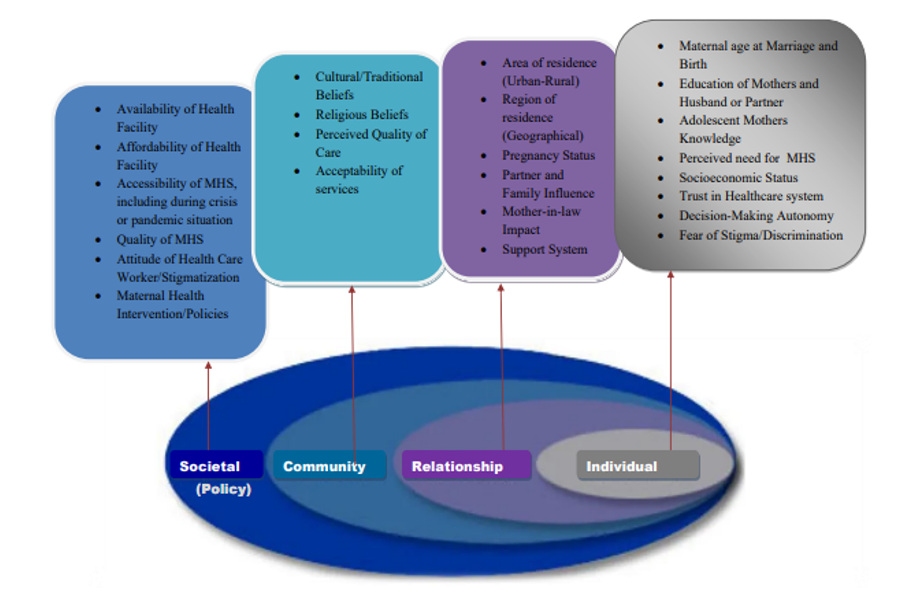

This study modified a socioecological model to classify the multiple interrelated factors influencing health-seeking behavior and the use of maternal health care among adolescent mothers in Nigeria.[14,47] The model was chosen because it pinpoints the demand-related (client-related) and supply-related (system-related) factors influencing maternal health-seeking behavior and the uptake of maternal health care. It explains the intricate relationships at the individual, interpersonal, community, and organization/policy levels.[14] This review employed the socioecological model (SEM) at individual, interpersonal, community, and organizational/policy levels.

Figure 1: Synthesis of results

Figure 2: PRISMA 2020 Flow Chart [132]

Results

Individual-Level Factors

Maternal age at marriage and childbirth:

The maternal health-seeking behaviour of adolescent mothers is influenced by the mother’s age at birth.[43,48,49] Poor and uneducated women frequently get married young, which puts them in danger of both an undesired pregnancy and death.[11,49,50] Maternal age at birth and use of maternal health care are significantly correlated.[51] Adolescent women used less maternal health care than older mothers, particularly in northern Nigeria, where child marriage is common.[43,45]

Educational status of mothers and husbands/partners:

One of the primary keys to improving maternal health and achieving the SDGs in general is education.[52] Education had a big impact on how many women used maternal health care.[53,54] The most important factor influencing adolescent mothers’ health-seeking behavior is the education level of both their husbands or partners and themselves.[43,55,56] Studies show that adolescent mothers and partners with at least a secondary education or higher level of education were more likely to use any maternal health care than those with no formal education.[43,55,56] This further proves that uneducated and underprivileged women do not employ expert birthing techniques, leaving them susceptible to impairments and maternal mortality.[45,56-59] Education also raises mothers’ awareness of the advantages of maternal health care and aids in their ability to make informed decisions regarding their health.[56,60]

Adolescent mothers knowledge and perceived need for maternal services:

Adolescent mothers’ use of prenatal, skilled delivery, and postpartum care may be influenced by their awareness of their risk for pregnancy difficulties and the advantages of maternal health services.[61] Significant correlations between maternal health-seeking behaviour and understanding of pregnancy risk have been found in studies.[10,61] Christian urban inhabitants in the southern part of Nigeria who are aware of the factors that contribute to maternal mortality exhibit better health-seeking behaviour than their rural counterparts in the northern part of Nigeria.[48,61] Furthermore, women in the Northern area were shown to have poor maternal health-seeking behaviour and to know little about the causes of maternal mortality and the advantages of maternal health care, which academics have linked to low levels of education and poverty.[48]

Socioeconomic status:

The likelihood of a skilful delivery was 10 times higher among wealthy women than among poor and vulnerable women.[62,63] Poor women in Nigeria cannot obtain maternal health treatments due to the high out-of-pocket costs, which increase access disparity to healthcare facilities.[62,64,65] Numerous adolescent mothers were not able to use maternal health services because of poverty, long travel times to medical facilities, and cultural barriers, especially those who live in remote regions.[12,62] As stated by academics, health-seeking behaviour is impacted by the high expense of healthcare.[62,64,65] This is consistent with other research, including the one conducted by Adedokun and colleagues, which found that the high cost of service is a major obstacle to using the mother and child health treatments that were offered.[12,56,66-68]

Trust in the health system:

According to studies, people’s and the entire community’s acceptance of maternal health care can be impacted by a lack of faith in the system.[59,69-71] Along with cultural and religious views, prior unpleasant personal experiences also have a role in the lack of faith people have in the healthcare system.[59,69-71] The utilization of maternal health services and mothers’ opinions of formal healthcare institutions are severely impacted by their prior delivery experiences.[59,69-71] Many women’s confidence in the official health system has been damaged by prior instances of poor care, abuse, and maltreatment by healthcare professionals, which has affected their choice to use maternal health services.[72-74] Mothers prefer traditional birth attendants so they can give birth in peace without any abuse or maltreatment of any type due to their belief in traditional birth practices as well as previous terrible experiences they had with healthcare professionals.[72-74]

Decision-making autonomy:

Some scholars stated that women who have control over their decisions and a favourable opinion of healthcare providers are more likely to receive maternal health treatments.[8,47,71,75-77] Osamor and colleagues find that Nigerian women have a low level of decision-making autonomy and link it to the fact that their husbands or partners are in charge of deciding on their medical care.[76] The study goes on to say that women’s decision-making about their health is predicted by their spouses’ occupations and educational backgrounds.[76] Fayomi and contemporaries further point out that patriarchal societies frequently inhibit the autonomy of women, and they go on to say that the biblical designation of males as the family’s head only strengthens their dominance.[78] Because they must wait for their spouses to provide financial support or seek authorization per religious or cultural standards, women with little decision-making autonomy have a lower adoption of professional birth delivery.[22,47,71,75-77,79-82]

Fear of stigma and discrimination:

The social repercussions of adolescent pregnancy and unmarried status include stigma, prejudice from peers, rejection from family, and violence by partners.[83-85] Adolescents are often expected to get pregnant in the western part of Nigeria only after being married, which exposes them to a lot of humiliation and prejudice.[22,85,86] Since they are frequently treated with contempt due to their young age during pregnancy, some people may be afraid to access official health services for fear of being judged and discriminated against by health professionals.[22,87-89] Namadi and colleagues, alongside other researchers, reveal that family members and neighbours view adolescent mothers as being wayward for being pregnant at a young age, against societal standards, and condemn and discriminate against them.[22,73,85-89]

Interpersonal-Level Factors

Area of residence (urban-rural) :

Research shows that where people live has an impact on the occurrence of adolescent pregnancies as well as the use of prenatal care and competent delivery.[59,90-92] Edward and colleagues’ studies show that adolescent mothers who live in urban areas frequently use maternal health facilities.[79,93] This is explained by the fact that people who live in cities frequently come from groups with higher incomes, have advanced degrees, and can afford to receive care from qualified caregivers.[79,93] In certain rural regions, home deliveries with inexperienced birth attendants are common, according to Garces and colleagues.[94] Other studies that explained that many pregnant women in rural regions give birth at home without a trained birth attendant, owing to a lack of information about the possible risks of pregnancy problems, financial limitations, and cultural views, were used to support this.[59,90-92,95,96]

Pregnancy status, partners/family influence, and mother-in-law’s impact:

Pregnancy status, partners/family influence, and mothers-in-law are significant factors in whether or not expert maternal health care is used.[59,69,71,82,97] A substantial correlation between pregnancy status, planned or unplanned, and health-seeking behaviour was found by researchers.[98] Peer pressure and family support have a big impact on how people behave while seeking out health.[98] In a different survey, mothers with more than four children frequently have negative views regarding using maternal health care.[99] Another researcher agrees that mothers-in-law’s views have a big impact on how their daughters-in-law seek out maternal health care. [97]

Support system:

Young women who lack sufficient parental support run the risk of not obtaining prenatal care. Reduced risks from adolescent pregnancy can be achieved with the aid of family and friends who provide positive encouragement for receiving prenatal care.[4,22,100] Teenagers who are pregnant may not be encouraged to sign up for or attend prenatal care without the necessary encouragement from their families or other reliable adults in the community.[4,22,100] Those who are experiencing severe early pregnancy symptoms may not be getting enough food, rest, or medical attention. Adolescent moms must have a strong social network to get the mental and physical support they need to be well during pregnancy and delivery.[4,22,100]

Community-Level Factors

Cultural and traditional beliefs:

As derived from research, some women prefer to engage untrained and traditional birth attendants instead of experienced medical personnel because of cultural norms and beliefs that lead them to believe that pregnancy and labour are unassisted, natural health processes.[12,81,96] Some researchers, as well as Adedokun et al. and Dada et al., showed that traditional beliefs, culture, and religion all have an impact on how often women use maternal health care and put both the mother and the unborn child at a high risk of illness or death.[30,56,78,81,96,101-103] Researchers observed that despite having the necessary information about pregnancy and its difficulties, adolescent mothers nevertheless demonstrated poor maternal health-seeking behaviour because of their religious and cultural backgrounds, which influence their attitudes.[30,56,78,81,96,101-103]

Most women favour traditional birth attendants (TBAs) because they think herbs should be consumed whole during pregnancy and labour and because they perceive TBAs to provide holistic care. Also, due to their fear of miscarriage or other pregnancy issues, most pregnant women put off signing up for prenatal care. They argue that witchcraft and supernatural powers can have an adverse effect on a pregnancy’s outcome.[12,96]

Religious belief:

Most rural residents frequently attribute religious justifications to every circumstance, which keeps qualified healthcare professionals from seeking assistance.[79,104] Additionally, some Muslims forbid male healthcare professionals from attending to their women, and some Christians refuse to use maternal health services because they oppose conventional medical practices.[79,82] According to studies, prenatal care and skilled delivery are more commonly used in the South than in the North, and northern Muslims are less likely to use maternal health services than southern Christians.[104-106] Women are also not expected to reveal their bodies to males who are not their spouses, such as male medical professionals. This may have an impact on their ability to make independent decisions about obtaining maternal health treatments and prevent their use of such services.[79,82,104-106]

Perceived quality of care/acceptability of service:

The way that women see maternal health care influences both their acceptance of the services and the results in terms of maternal health.[107-109] According to studies, the unfavourable impression that healthcare professionals are unfriendly contributes to the low adoption of maternal health treatments.[107-110] The acceptance and use of maternal care are also impacted by the public’s opinion of it. Mothers’ perceptions of the acceptability and uptake of maternal health services determine whether they are provided for free or not. Mother’s perceptions are also influenced by the attitude of healthcare providers, the perceived quality of their care, and their level of trust in the existing health system.[108,109]

Kola and colleagues also found evidence of healthcare professionals’ unfavourable sentiments toward adolescents who are pregnant because of societal beliefs in sexual celibacy until marriage. The acceptance of and access to maternal health treatments are significantly hampered by this unfavourable stereotype.[109] Some women choose to seek care from subpar maternity homes because they believe these facilities are more compassionate, which influences how acceptable maternal health services are seen. In line with Ndegwa et al., competent care providers who are unsupportive, particularly towards teenage moms, because of the negative stereotype about teenage pregnancy, spend less time caring for pregnant women than TBAs.[108]

Organisational/Policy Level Factors

Availability of health facilities:

Due to the lack of institutional facilities in their communities, more than half of Nigerian women have had difficulty obtaining maternity health treatments.[68,79,80] Scholars show that the lack of high-quality healthcare facilities in rural regions correlates with poor maternal health-seeking behaviour and unfavourable health outcomes.[79] The provision of quality maternal health services throughout pregnancy can assist in lowering maternal mortality. According to research, rural residents in Nigeria frequently experience neglect in terms of the distribution of health facilities.[68,79,80] Even in areas with access to healthcare facilities, there aren’t enough trained caregivers or the right tools.[79]

Affordability of quality maternal health services:

Another element influencing health-seeking behaviour is the availability of maternal health care that is both inexpensive and accessible. Teenagers may not be able to pay for service prices since they often earn less than adults, according to Nigeria’s excessive reliance on out-of-pocket expenditures.[57] According to a survey, the majority of adolescents still depend on parents or other family members for financial support to use the available health services, making it challenging for them to pay for maternal health care.[57,111] Ekpenyong and colleagues found that because the poor may not be able to pay the cost of care, the cost of treatment affects both women’s decision-making about the use of maternal health services and the attitudes of healthcare staff.[111]

Attitudes of healthcare workers:

The stigma or prejudice connected with the services has an impact on how people behave while seeking health care.[57,100,111-116] According to research, healthcare professionals’ opinions have an impact on how often pregnant women use maternal health services, particularly among adolescent moms.[117,118] For instance, Ishola and colleagues report that certain healthcare personnel in Nigeria abuse and discriminate against Nigerian women during childbirth, which is one of the reasons some women choose not to give birth in a hospital.[117]

Afulani et al. and Ziblim et al demonstrated that certain healthcare professionals’ attitudes toward adolescent mothers throughout pregnancy and childbirth might discourage them from seeking out maternal health treatments.[118,119] Maternal health services are not being used as a result of negative attitudes of healthcare professionals, including slapping, bodily restraint of the bed during birth, and hospital detention of moms who cannot afford to pay for delivery expenses.[117] Additionally, adolescent moms want readily available, reasonably priced maternal health services; they demand care that is completely private, respectful, and free of bias.[120]

Discussion

The review of studies discovered that practically all individual characteristics have an impact on how people behave while seeking health care and how often they utilize maternal health services. Pregnancy outcomes are influenced by the mother’s age at conception and marriage. Teenagers who become pregnant at this age are more prone to fatal pregnancy problems and other dangers. Marriage is frowned upon for this age group in the western portion of Nigeria, where most people are already married. As a result, once a girl gets pregnant, her family and society frequently discriminate against her.

Adolescent women who become mothers often become school dropouts. They run the risk of being unemployed and running into financial trouble in the future because of their poor level of education. Because they cannot access or afford maternity services owing to poverty and lack of information about the risk of pregnancy problems, poor and uneducated women are more likely to experience pregnancy issues. Adolescents’ decisions to seek out maternal health treatments are influenced by sociocultural norms in a patriarchal nation like Nigeria and a lack of decision autonomy.[95] Additionally, a lack of understanding of the risks linked with pregnancy and illiteracy has an impact on their behaviour when seeking out maternal health treatments.

In addition, cultural or religious beliefs that exclude using conventional medications or giving birth in a hospital, and a lack of faith in the health system (caused by a prior unpleasant experience with services) have an impact on the adoption of maternal health care. These results are important for addressing personal obstacles to utilizing maternal health care. Nigeria, with a high youthful population of over 43 per cent, offers tremendous economic potential for adequate investment in adolescent health. To improve females’ health-seeking behaviour, it is essential to emphasize the importance of education. One specific behaviour modification strategy that might influence her use of maternal health care is increasing her understanding of the risks connected to adolescent pregnancies.

Most of the publications discussed both favourable and unfavourable impacts of location and region on health-seeking behaviour and utilization of maternal health care. Mothers in metropolitan regions frequently seek out maternal health care compared to their counterparts in rural areas. Regional differences in MMR show that the northern area has a higher-than-average rate of low consumption of maternal health services.[121,122] This discrepancy was linked to widespread rural poverty, poor partner and mother education levels, cultural and religious views, and long travel times to medical facilities.[90]

The results demonstrate how a strong support network has a big impact on healthy behaviour.[114] The majority of adolescent pregnancies are not planned; if they do not receive the necessary help, they may resort to illegal means to end the pregnancy, incurring risks or perhaps dying as a result. For young moms to have the required physical and emotional assistance to be healthy during pregnancy and childbirth, they need to have adequate support from their partners, families, mother-in-law, and the community.[1,123,124]

The decision to get maternal health treatments by a woman is strongly influenced by her cultural and religious beliefs. Nigeria is home to many different cultures, some of which have an impact on how women seek out health care and use it. For instance, some women opt to engage traditional birth attendants rather than qualified professionals because of cultural prejudices and misconceptions about pregnancy. Because they think that disclosing their pregnant status may subject them to witchcraft and supernatural powers, some women delay enrolling in prenatal care until it is too late.[109,112] Due to their belief in herbs, holy water, anointing oil, or other objects regarded as sacred, some people who even register early nonetheless prefer to deliver with the TBA at churches or other places of worship. The acceptance of maternal health care is also impacted by cultural norms that view pregnancy and delivery as effortless, natural occurrences.

In a similar vein, northern Muslims use less maternal health care than southern Christians. Male healthcare professionals were forbidden by fanatical Muslims, particularly in northern Nigeria, from caring for their women, while some Christians disapprove of the use of modern medicine. Moreover, most rural residents gave spiritual significance to every circumstance. Their behaviour in seeking health is impacted by these various ideas. Poor health-seeking behaviour among northern Muslim women is influenced by healthcare staff’s insensitivity to religious demands, cultural influences, and financial dependency on spouses or partners.[118] According to other research, patriarchal and hierarchical societies, where males frequently exert extensive control over women’s autonomy in decision-making, are to blame for Nigeria’s poor adoption of maternal health care.[83] These findings emphasize the necessity for raising knowledge about the negative effects of cultural and religious beliefs that are used by traditional leaders and religious institutions to persuade their followers of the value of formal maternal health treatments. To be able to give quality treatment regardless of cultural or religious convictions, healthcare professionals should also get training on cultural competency.

The results of this review demonstrate the significance of several health-related determinants and policies and how they influence behaviour linked to seeking health care and utilization of maternal health services. It is impossible to overstate the value of official maternity services. The results demonstrate that women who received expert maternal health care had better pregnancy outcomes and more successfully adapted to postpartum life than those who did not.[125-128] However, more than 50% of Nigerian women indicated that some locations lacked official health facilities and made it difficult to get prenatal care. In Nigeria, rural residents are frequently overlooked when allocating health facilities. Where there are healthcare facilities, there are either no qualified caregivers or no delivery tools to take care of patients. Due to poverty, bad roads, a lack of awareness of the benefits of maternal health care, and vast travel distances between their place of residence and the nearest medical facilities, many rural residents also display poor uptake of maternal health services. Adolescent mothers are pushed away by healthcare professionals’ unfavourable and judgmental attitudes toward them throughout pregnancy and delivery, which has an impact on the acceptability and use of maternal health services. Because they are thought to provide supportive care, most women choose to have their babies with inexperienced birth attendants.

The issues related to adolescent mothers who are already pregnant are never addressed by national initiatives that seek to expand access to high-quality reproductive health information and services for adolescents and young people. Additionally, this regulation created a minimum age requirement for several of these services, making it challenging for teenagers under the age of 18 to use them.

Additionally, adolescent mothers’ age-specific requirements were not met by the available maternal health services. Adolescent moms prefer readily available, reasonably priced maternal health services; they also demand to be treated with the utmost respect, privacy, and dignity while seeking treatment.[73,129-131] Adolescent mothers unique needs must be the focus of policies and programs if we are to increase their use of maternal health care.

Conclusion

This review concludes that numerous factors affecting health-seeking behaviors and the uptake of maternal health services by adolescent mothers in Nigeria cut across all levels of the socioecological model. The major factors include maternal age, low education level, poverty, low decision-making autonomy, stigmatization and discrimination, healthcare workers judgmental attitude, and inability to access and afford the cost of health facilities. Adolescent mothers prefer accessible and affordable maternal health services; they want to be treated with utmost privacy and respect, and not be judged when seeking care. However, the available maternal health services do not target adolescent mothers’ health and developmental needs.

The national policies that aim to increase access to quality reproductive health information and services for adolescents and young people only address the reduction of adolescent pregnancy, but never address problems associated with poor uptake of maternal health services by adolescent mothers. In addition, the existing strategies to improve the uptake of maternal health services target the underserved populace and are promising strategies because of the reported success rate; however, they are not sustainable. Therefore, policymakers need to explore sustainable sources of generating funds for the sustainability of existing strategies.

References

- Diabelková J, Rimárová K, Dorko E, Urdzík P, Houžvičková A, Argalášová Ľ. Adolescent pregnancy outcomes and risk factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(5):0-9. doi:10.3390/ijerph20054113 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- World Health Organization. Adolescent pregnancy. WHO Fact sheet. Published 2023. Accessed October 10, 2024. Adolescent pregnancy

- Nam JY, Oh SS, Park EC. The association between adequate prenatal care and severe maternal morbidity among teenage pregnancies: a population-based cohort study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:782143. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.782143 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lambonmung A, Acheampong CA, Langkulsen U. The effects of pregnancy: a systematic review of adolescent pregnancy in Ghana, Liberia, and Nigeria. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;20(1):605. doi:10.3390/ijerph20010605 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Oluma FA, Gabriel TS, Kasim M, et al. The role of the World Health Organisation and related funds on maternal and child health in Nigeria. Prevention. 2023;2(2):14-31. doi:10.56626/egis.v2i2.12965. Crossref | Google Scholar

- Akeju DO, Oladapo OT, Vidler M, et al. Determinants of health care seeking behaviour during pregnancy in Ogun State, Nigeria. Reprod Health. 2016;13(Suppl 1):32. doi:10.1186/s12978-016-0139-7 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Adebowale SA, Akinyemi JO. Determinants of maternal utilization of health services and nutritional status in a rural community in South-West Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2016;20(2):72-85. doi:10.29063/ajrh2016/v20i2.8 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Alex-Ojei CA, Odimegwu CO, Ntoimo LFC. A qualitative investigation into pregnancy experiences and maternal healthcare utilisation among adolescent mothers in Nigeria. Reprod Health. 2023;20(1):77. doi:10.1186/s12978-023-01613-z PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Singh N, Sethi A. Endometritis – Diagnosis,Treatment and its impact on fertility – A Scoping Review. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2022;26(3):538-546. doi:10.5935/1518-0557.20220015 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Maheshwari MV, Khalid N, Patel PD, Alghareeb R, Hussain A. Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes of Adolescent Pregnancy: A Narrative Review. Cureus. 2022;14(6):e25921. doi:10.7759/cureus.25921 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Oyeyemi AL, Aliyu SU, Sa’ad F, et al. Association between adolescent motherhood and maternal and child health indices in Maiduguri, Nigeria: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e024017. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024017 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Akeju DO, Oladapo OT, Vidler M, et al. Determinants of health care seeking behaviour during pregnancy in Ogun State, Nigeria. Reprod Health. 2016;13(Suppl 1):32. doi:10.1186/s12978-016-0139-7 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Asante KO, Kugbey N, Osafo J, Quarshie EN-B, Sarfo JO. The prevalence and correlates of suicidal behaviours (ideation, plan and attempt) among adolescents in senior high schools in Ghana. SSM Popul Health. 2017;3:427-434. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.05.005 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Oppong J, Moore A, Hudak P, Ebeniro J. The geography of maternal mortality in Nigeria. In: Geographies of Health and Development. 2020:49-64. doi:10.4324/9781315584379-10 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Folorunsho-Francis A. Nigeria’s maternal mortality rate worst in the world – Ehanire. Healthwise blog. 2025. Nigeria’s maternal mortality rate worst in the world – Ehanire

- World Health Organization. Maternal mortality. WHO Fact sheet. Published 2023. Accessed October 10, 2024. Maternal mortality

- Yakubu I, Salisu WJ. Determinants of adolescent pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):15. doi:10.1186/s12978-018-0460-4 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mekonnen T, Dune T, Perz J. Maternal health service utilisation of adolescent women in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic scoping review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:366. doi:10.1186/s12884-019-2501-6 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Noori N, Proctor JL, Efevbera Y, Oron AP. Effect of adolescent pregnancy on child mortality in 46 countries. BMJ Global Health. 2022;7(5).doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007681 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- World Health Organization. Newborns: improving survival and well-being. 2020. Accessed November 2, 2023. Newborn mortality (who.int)

- United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. Under-five mortality – UNICEF data. 2023. Accessed November 2, 2023. Child Mortality – UNICEF DATA

- Mekwunyei LC, Odetola TD. Determinants of maternal health service utilisation among pregnant teenagers in Delta State, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:81. doi:10.11604/pamj.2020.37.81.16051 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Otu A, Ukpeh I, Okuzu O, Yaya S. Leveraging mobile health applications to improve sexual and reproductive health services in Nigeria: implications for practice and policy. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):1-5. doi:10.1186/s12978-021-01051-2 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ajegbile ML. Closing the gap in maternal health access and quality through targeted investments in low-resource settings. J Glob Heal Reports. 2023;7(1):1-5. doi:10.29392/joghr.2023.000001 Crossref | Google Scholar

- United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. Maternal mortality UNICEF data. 2021. Accessed November 2, 2023. Maternal mortality rates and statistics – UNICEF DATA

- Suzuki EMI, K Charles, M Samuel. Progress in reducing maternal mortality has stagnated and we are not on track to achieve the SDG target: new UN report. World Bank Blogs. February 22, 2023. Accessed November 2, 2023. Progress in reducing maternal mortality has stagnated and we are not on track to achieve the SDG target: new UN report

- Our World in Data team. Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. 2023. Accessed November 2, 2023. Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages – Our World in Data

- UN Women SDG 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. 2023. Accessed November 2, 2023. In focus: Women and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): SDG 3: Good health and well-being | UN Women – Headquarters

- World Health Organization. SDG Target 3.1 | Maternal mortality: By 2030, reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100 000 live births. 2023. Accessed November 2, 2023. SDG Target 3.1 | Maternal mortality: By 2030, reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100 000 live births (who.int)

- Adedokun ST, Uthman OA, Bisiriyu LA. Determinants of partial and adequate maternal health services utilization in Nigeria: analysis of cross-sectional survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23(1):457. doi:10.1186/s12884-023-05712-4 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Aliyu L, Kadas AS, Mohammed A, et al. Impediments to maternal mortality reduction in Africa: a systemic and socioeconomic overview. J Perinat Med. 2022;51(2):202-207. doi:10.1515/jpm-2022-0052 PubMed | Crossref |

Google Scholar - Mekonnen T, Dune T, Perz J. Maternal health service utilisation of adolescent women in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic scoping review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):366. doi:10.1186/s12884-019-2501-6 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Idowu A, Olowookere SA, Abiola OO, Akinwumi AF, Adegbenro C. Determinants of skilled care utilization among pregnant women residents in an urban community in Kwara State, Northcentral Nigeria. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2017;27(3):291-298. doi:10.4314/ejhs.v27i3.11 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Okoli CI, Hajizadeh M, Rahman MM, Velayutham E, Khanam R. Socioeconomic inequalities in teenage pregnancy in Nigeria: evidence from Demographic Health Survey. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1729. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-14146-0 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Soumah, A., Balde, M., Camara, B., et al. (2022) Factors Associated with the Continuum of Prenatal Care in the Post-Ebola Context in Guinea. Open Journal of Epidemiology. 2022;12:207-220. doi:10.4236/ojepi.2022.122017 Crossref | Google Scholar

- World Health Organization. More than 1.2 million adolescents die every year, nearly all preventable. 2017. Accessed June 13, 2021. More than 1.2 million adolescents die every year, nearly all preventable (who.int)

- Mekonnen T, Dune T, Perz J. Maternal health service utilisation of adolescent women in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic scoping review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):191. doi:10.1186/s12884-019-2501-6 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- March of Dimes. Maternal death and pregnancy-related death. 2021. Accessed November 2, 2023. Maternal death and pregnancy-related death | March of Dimes

- Brindis CD, Decker MJ, Gutmann-Gonzalez A, Berglas NF. Perspectives on Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention Strategies in the United States: Looking Back, Looking Forward. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2022;13:107-108. doi:10.2147/AHMT.S402218 PubMed | Crossref

- Shitie A, Assefa N, Dhressa M, Dilnessa T. Completion and factors associated with maternity continuum of care among mothers who gave birth in the last one year in Enemay District, Northwest Ethiopia. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2020;2020:7019676. doi:10.1155/2020/7019676 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Stowasser T, Heiss F, McFadden D, Winter J. Healthy, Wealthy and Wise?” Revisited: An Analysis of the Causal Pathways from Socio-economic Status to Health. Natl Bur Econ Res. Published online 2011:267-317. doi:10.3386/w17273 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Olibamoyo O, Ola B, Coker O, Adewuya A, Onabola A. Trends and patterns of suicidal behaviour in Nigeria: mixed-methods analysis of media reports from 2016 to 2019. S Afr J Psychiatr. 2021;27:1572. doi:10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v27i0.1572 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Alex-Ojei CA, Odimegwu CO. Correlates of antenatal care usage among adolescent mothers in Nigeria: a pooled data analysis. J Adolesc. 2021;61(1):38-49. doi:10.1080/03630242.2020.1844359 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Banke-Thomas A, Banke-Thomas O, Kivuvani M, Ameh CA. Maternal health services utilisation by Kenyan adolescent mothers: analysis of the Demographic Health Survey 2014. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2017;12:37-46. doi:10.1016/j.srhc.2017.02.004 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Banke-Thomas OE, Banke-Thomas AO, Ameh CA. Factors influencing utilisation of maternal health services by adolescent mothers in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):65. doi:10.1186/s12884-017-1246-3 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- World Health Organization. World health statistics 2018: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. 2018. Accessed May 31, 2021. World health statistics 2018: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals (who.int)

- Okedo-Alex IN, Akamike IC, Ezeanosike OB, Uneke CJ. Determinants of antenatal care utilisation in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e031890. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-03189048 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mekwunyei LC, Odetola TD. Determinants of maternal health service utilisation among pregnant teenagers in Delta State, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:81. doi:10.11604/pamj.2020.37.81.16051 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Khaki J, Sithole L. Factors associated with the utilization of postnatal care services among Malawian women. Malawi Med J. 2019;31(1):2-11. doi:10.4314/mmj.v31i1.2 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Bolarinwa OA, Sakyi B, Ahinkorah BO, et al. Spatial Patterns and Multilevel Analysis of Factors Associated with Antenatal Care Visits in Nigeria: Insight from the 2018 Nigeria Demographic Health Survey. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(10):1389. doi:10.3390/healthcare9101389 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Imo, Chukwuechefulam & Isiugo-Abanihe, Uche & Chikezie, David. Socioeconomic determinants of under-five children health outcome among childbearing mothers in Abia state, Nigeria. International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology. 2017;9(2):17-27.

doi:10.5897/IJSA2016.0678 Crossref | Google Scholar - Weitzman A. The effects of women’s education on maternal health: evidence from Peru. Soc Sci Med. 2017;180:1-9. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.004 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ogu RN, Agholor KN, Okonofua FE. Engendering the attainment of the SDG-3 in Africa: overcoming the socio-cultural factors contributing to maternal mortality. Afr J Reprod Health.2016;20(3):62-74. doi:10.29063/ajrh2016/v20i3.11 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Onwujekwe O, Ezumah N, Mbachu C, et al. Exploring effectiveness of different health financing mechanisms in Nigeria: what needs to change and how can it happen? BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:661. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4512-4 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- National Population Commission. 2018 Demographic and Health Survey Key Findings. 2019. Accessed April 5, 2021. Demographic and Health Survey Key Findings

- Adedokun ST, Uthman OA. Women who have not utilized health services for delivery in Nigeria: who are they and where do they live? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):93. doi:10.1186/s12884-019-2242-6 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kifle D, Azale T, Gelaw YA, Melsew YA. Maternal health care service seeking behaviors and associated factors among women in rural Haramaya District, Eastern Ethiopia: a triangulated community-based cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):6. doi:10.1186/s12978-016-0270-5 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- World Health Organization. Health financing policy brief no. 6 – purchasing health services for universal health coverage: how to make it more strategic? 2019. WHO-UCH-HGF-PolicyBrief-19.6-eng.pdf

- Somefun OD, Ibisomi L. Determinants of postnatal care non-utilization among women in Nigeria. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:21. doi:10.1186/s13104-015-1823-3 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Rai RK, Singh PK, Kumar C, Singh L. Factors associated with the utilization of maternal health care services among adolescent women in Malawi. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;32(2):106-125. doi:10.1080/01621424.2013.779354 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Oguntunde O, Nyenwa J, Yusuf F, Dauda DS, Salihu A, Sinai I. Factors associated with the knowledge of obstetric danger signs, and perceptions of the need for obstetric care amongst married young women in northern Nigeria. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2021;13(1):2557. doi:10.4102/phcfm.v13i1.2557 PubMed | Crossref |

Google Scholar - Global Burden of Disease Health Financing Collaborator Network. Trends in future health financing and coverage: future health spending and universal health coverage in 188 countries, 2016-40. Lancet. 2018;391(10132):1783-1798. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30697-4 PubMed | Crossref

- Premium Times. Basic Health Care Provision Fund: A Slow Start to a Long Journey. 2021. Accessed August 7, 2021. Basic Health Care Provision Fund: A Slow Start to a Long Journey (premiumtimesng.com)

- The World Bank. Nigeria releases new report on poverty and inequality in country. The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). 2020. Accessed May 26, 2021. datacatalogfiles.worldbank.org/ddh-published/0064942/DR0092448/Global_POVEQ_NGA.pdf?versionId=2024-04-16T15:19:00.4018291Z

- Statista. Nigeria: poverty rate, by state 2019. 2021. Accessed May 31, 2021. Nigeria: poverty rate, by state | Statista

- Okpani AI, Abimbola S. The midwives service scheme: a qualitative comparison of contextual determinants of the performance of two states in central Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:1-16. doi:10.1186/s41256-016-0017-4 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ochieng CA, Odhiambo AS. Barriers to formal health care seeking during pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal period: a qualitative study in Siaya County in rural Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):339. doi:10.1186/s12884-019-2485-2 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Chibueze Nwadinobi G, Chima FO, Ojobah C. Social Economic Determinants of Maternal Mortality in Rural Communities of Umuahia North Local Government Area in Abia State, Nigeria. Int J Humanit Soc Sci Rev. 2020;6(3):1-9. 1-5.pdf (ijhssrnet.com)

- Shahabuddin A, Delvaux T, Nöstlinger C, et al. Maternal health care-seeking behaviour of married adolescent girls: A prospective qualitative study in Banke District, Nepal. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0217968. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217968 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Shahabuddin A, Nöstlinger C, Delvaux T, et al. Exploring maternal health care-seeking behavior of married adolescent girls in Bangladesh: a social-ecological approach. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169109. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169109 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Gopalakrishnan S, Anantha Eashwar VM, Muthulakshmi M. Health-seeking behaviour among antenatal and postnatal rural women in Kancheepuram District of Tamil Nadu: a cross-sectional study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(3):1035-1042. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_323_18 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Okafor II, Ugwu EO, Obi SN. Disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in a low-income country. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;128(2):110-113. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.08.015 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kruk ME, Kujawski S, Mbaruku G, Ramsey K, Moyo W, Freedman LP. Disrespectful and abusive treatment during facility delivery in Tanzania: a facility and community survey. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(1):e26-e33. doi:10.1093/heapol/czu079 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Aziato L, Odai PNA, Omenyo CN. Religious beliefs and practices in pregnancy and labour: an inductive qualitative study among post-partum women in Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:138. doi:10.1186/s12884-016-0920-1 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Alemayehu M, Meskele M. Health care decision making autonomy of women from rural districts of Southern Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:213–221. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S131139 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Osamor P, Grady C. Factors associated with women’s health care decision-making autonomy: empirical evidence from Nigeria. Health Policy Plan. 2018;50(1):70-85. doi:10.1017/S0021932017000037 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Brizuela V, Tunçalp Ö. Global initiatives in maternal and newborn health. Perspect Public Health. 2017;10(1):21-25. doi:10.1177/1753495X16684987 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Azuh D, Fayomi O, Ajayi L. Socio-cultural factors of gender roles in women’s healthcare utilization in Southwest Nigeria. J Soc Sci. 2015;3(4):1-10. doi:10.4236/jss.2015.34013 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Uche EO. Factors affecting health seeking behaviour among rural dwellers in Nigeria and its implication on rural livelihood. Eur J Soc Sci Stud. 2017;2(2). doi:10.46827/ejsss.v0i0.70 Google Scholar

- Chukwuma A, Ekhator-Mobayode UE. Armed conflict and maternal health care utilization: Evidence from the Boko Haram Insurgency in Nigeria. Soc Sci Med. 2019;226:104-112. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.02.055 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Dada AA. Factors affecting maternal health seeking behaviour in a Yoruba community of Nigeria: An analysis of socio-cultural beliefs and practices. PhD thesis. University of Kwa-Zulu-Nata; 2019. Accessed July 1, 2021. Factors affecting maternal health seeking behaviour in a Yoruba community of Nigeria: an analysis of socio-cultural beliefs and practices. (ukzn.ac.za)

- MCSP Nigeria. Sokoto State Family Planning Costed Implementation Plan. 2018. Accessed October 9, 2024.

Sokoto State Family Planning Costed Implementation Plan - Human Rights Watch. Leave No Girl Behind in Africa: Discrimination in Education Against Pregnant Girls and Adolescent Mothers. 2018. Accessed October 9, 2024. Leave No Girl Behind in Africa: Discrimination in Education against Pregnant Girls and Adolescent Mothers

- Africa Check. FACTSHEET: Understanding Nigeria’s teenage pregnancy burden. 2021. Accessed October 9, 2024. FACTSHEET: Understanding Nigeria’s teenage pregnancy burden

- Aládésanmí Ọ́A, Ògúnjìnmí ÍB. Yorùbá thoughts and beliefs in childbirth and child moral upbringing: a cultural perspective. Adv Appl Sociol. 2019;9(12):41041. doi:10.4236/aasoci.2019.912041 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Agunbiade OJ, Titilayo A, Opatola M. Pregnancy stigmatization and coping strategies of adolescent mothers in two Yoruba communities, Southwestern Nigeria. Paper presented at: XXVI IUSSP International Population Conference; September 27–October 2, 2009; Marrakech, Morocco. Pregnancy Stigmatisation and Coping Strategies of Adolescent Mothers in two Yoruba Communities , Southwestern Nigeria By AGUNBIADE

- Hackett K, Lenters L, Vandermorris A, LaFleur C, Newton S, Ndeki S, Zlotkin S. How can engagement of adolescents in antenatal care be enhanced? Learning from the perspectives of young mothers in Ghana and Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:184. doi:10.1186/s12884-019-2326-3 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Namadi HM, Msughter AE. Survey of reproductive health information seeking behaviour among pregnant women in some selected hospitals in Kano metropolis, Nigeria. Biology and Medicine. 2020;30(5):23699-23708. doi:10.26717/BJSTR.2020.30.005006 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Olonade O, Olawande TI, Alabi OJ, Imhonopi D. Maternal mortality and maternal health care in Nigeria: implications for socio-economic development. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019 Mar 14;7(5):849-855. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2019.041 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Fagbamigbe AF, Idemudia ES. Wealth and antenatal care utilization in Nigeria: policy implications. Health & Social Work. 2017 Jan;38(1):17-37. doi:10.1080/07399332.2016.1225743 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Agho KE, Ezeh OK, Ogbo FA, Enoma AI, Raynes-Greenow C. Factors associated with inadequate receipt of components and use of antenatal care services in Nigeria: a population-based study. International Health. 2018 May 1;10(3):172-181. doi:10.1093/inthealth/ihy011 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Oyedele D. Nigeria’s incidence of teenage pregnancies is unacceptably high. D+C – Development + Cooperation. 2017. Accessed May 13, 2021. Face the truth (dandc.eu)

- Iacoella F, Tirivayi N. Determinants of maternal healthcare utilization among married adolescents: evidence from 13 sub-Saharan African countries. Public Health. 2019;175:119-129. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2019.07.002 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Garces A, McClure EM, Chomba E, et al. Home birth attendants in low income countries: who are they and what do they do? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012 May 14;12:34. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-12-34 PubMed | Crossref |

Google Scholar - El-Hadj Imorou S. Socio-economic and health determinants of rural households consent to prepay for their health care in N’Dali (North of Benin). Open Journal of Social Sciences. 2020;8:348-360. doi:10.4236/jss.2020.85024 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mbaya N. Influence of Social-Cultural Factors on Women Preference for Traditional Birth Attendants Services: A Case of Nakuru County, Kenya. Master’s thesis. Kenyatta University; 2017. Influence of Social-cultural Factors on Women Preference for Traditional Birth Attendants Services: a Case of Nakuru County, Kenya (uonbi.ac.ke)

- White D, Dynes M, Rubardt M, Sissoko K, Stephenson R. The influence of intrafamilial power on maternal health care in Mali: perspectives of women, men, and mothers-in-law. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2013 Jun;39(2):58-68. doi:10.1363/3905813 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ilyn W. Factors determining antenatal health seeking behavior of adolescent mothers at the antenatal clinic in Naivasha District Hospital, Kenya. Master’s thesis. University of Nairobi; 2012. Factors determining antenatal health seeking behavior of adolescent mothers at the antenatal clinic in Naivasha District Hospital, Kenya

- WHO. Adolescent pregnancy. 2024. Adolescent pregnancy

- Okeke SR, Idriss-Wheeler D, Yaya S. Adolescent pregnancy in the time of COVID-19: what are the implications for sexual and reproductive health and rights globally? Reprod Health. 2022;19(1):207. doi:10.1186/s12978-022-01505-8 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Olakunde BO, Adeyinka DA, Mavegam BO, et al. Factors associated with skilled attendants at birth among married adolescent girls in Nigeria: evidence from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, 2016/2017. Int Health. 2019 Nov 13;11(6):545-550. doi:10.1093/inthealth/ihz017 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Dafi M, Lackshman IM, Abeysinghe D, Jidda KI. Socio-cultural and health-seeking beliefs in maternal health care utilization among women in rural Nigeria. Int J Edu. 2018;1:1-10. Accessed July 1, 2021. Socio-cultural and health-seeking beliefs in maternal health care utilization among women in rural Nigeria

- Roberts J, Hopp Marshak H, Sealy D-A, Manda-Taylor L, Mataya R, Gleason P. The role of cultural beliefs in accessing antenatal care in Malawi: a qualitative study. Public Health Nursing. 2017;34(1):42-49. doi:10.1111/phn.12242 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Al-Mujtaba M, Cornelius LJ, Galadanci H, Erekaha S, Okundaye JN, Adeyemi OA, Sam-Agudu NA. Evaluating religious influences on the utilization of maternal health services among Muslim and Christian women in North-Central Nigeria. International Journal of Maternity and Neonatal Health. 2016:3645415. doi:10.1155/2016/3645415 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ganle JK. Why Muslim women in Northern Ghana do not use skilled maternal healthcare services at health facilities: a qualitative study. BMC International Health and Human Rights. 2015;15:10. doi:10.1186/s12914-015-0048-9 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Pushpalata NK, Chandrika KB. Health care seeking behaviour-A theoretical perspective. Paripex Indian J Res. 2017;6(1):790-2. Health care seeking behaviour-A theoretical perspective

- Balde MD, Diallo BA, Bangoura A et al. Perceptions and experiences of the mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities in Guinea: a qualitative study with women and service providers. Reproductive Health. 2017;14:3. doi:10.1186/s12978-016-0266-1 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ndegwa MN. Factors influencing uptake of antenatal care in Taita Taveta County, Kenya. Master’s thesis. University of Kenya Methodist University.; 2019. Accessed August 1, 2021. Factors influencing uptake of antenatal care in Taita Taveta County, Kenya

- Kola L, Bennett IM, Bhat A, et al. Stigma and utilization of treatment for adolescent perinatal depression in Ibadan Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):294. doi:10.1186/s12884-020-02970-4 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Edu BC, Agan TU, Monjok E, Makowiecka K. Effect of free maternal health care program on health-seeking behaviour of women during pregnancy, intra-partum and postpartum periods in Cross River State of Nigeria: a mixed method study. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5(3):370–382. Published online 2017 Jun 11. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2017.075 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ekpenyong MS. Challenges of maternal and prenatal care in Nigeria. January 2019. doi:10.21767/2471-8505.100125 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ajayi AI, Athero S, Muga W, Kabiru CW. Lived experiences of pregnant and parenting adolescents in Africa: A scoping review. Reprod Health. 2023;20(1):113. doi:10.1186/s12978-023-01654-4 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Girum T, Wasie A. Correlates of maternal mortality in developing countries: an ecological study in 82 countries. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2017;3:19. doi:10.1186/s40748-017-0059-8 PubMed | Crossref |

Google Scholar - Akaba G, Dirisu O, Okunade K, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on utilization of maternal, newborn and child health services in Nigeria: protocol for a country-level mixed-methods study. F1000Res. 2020;9:1106. doi:10.12688/f1000research.26283.2 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Stangl AL, Earnshaw VA, Logie CH, et al. The health stigma and discrimination framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019;17:31. doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Pant S, Koirala S, Subedi M. Access to maternal health services during COVID-19. EJMS. 2020;2(2). doi:10.46405/ejms.v2i2.110 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ishola F, Owolabi O, Filippi V. Disrespect and abuse of women during childbirth in Nigeria: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0174084. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0174084 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Afulani PA, Kelly AM, Buback L, et al. Providers’ perceptions of disrespect and abuse during childbirth: a mixed-methods study in Kenya. Health Policy Plan. 2020;35(5):577-586. doi:10.1093/heapol/czaa009 PubMed | Crossref |

Google Scholar - Ziblim S-D, Yidana A, Mohammed A-R. Determinants of Antenatal Care Utilization among Adolescent Mothers in the Yendi Municipality of Northern Region, Ghana. Ghana J Geogr. 2018;10(1):78-97. Determinants of Antenatal Care Utilization among Adolescent Mothers in the Yendi Municipality of Northern Region, Ghana | Ghana Journal of Geography (ajol.info)

- Owolabi O, Wong KLM, Dennis ML, et al. Comparing the use and content of antenatal care in adolescent and older first-time mothers in 13 countries of West Africa: a cross-sectional analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys. E Clinical Medicine. 2017;1(3):203-212.

doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(17)30025-1 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - The World Bank. Development Projects: Nigeria – Program to Support Saving One Million Lives – P146583. 2022. Accessed July 30, 2021. What We do

- Benjet C, Bromet E, Karam EG, et al. The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychol Med. 2016;46(2):327-343. doi:10.1017/S0033291715001981 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- World Health Organization. Key Country Indicators | Nigeria – key indicators. WHO. 2016. Accessed June 7, 2021. Key Country Indicators | Nigeria – key indicators

- Antsaklis A, Papamichail M, Antsaklis P. Maternal mortality: What are women dying from? Donald School J Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;14(1):64–69. Maternal Mortality: What are Women Dying from?

- United Nations Fund for Population Activities. The Social determinants of maternal death and disability. 2012. Accessed June 24, 2021. The Social determinants of maternal death and disability

- Speizer IS, Story WT, Singh K. Factors associated with institutional delivery in Ghana: the role of decision-making autonomy and community norms. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:398. doi:10.1186/s12884-014-0398-7 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Benjet C, Bromet E, Karam EG, et al. The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychol Med. 2016;46(2):327-343. doi:10.1017/S0033291715001981 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Namutebi M, Kabahinda D, Mbalinda SN, et al. Teenage first-time mothers’ perceptions about their health care needs in the immediate and early postpartum period in Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22:743. doi:10.1186/s12884-022-05062-7 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mannava P, Durrant K, Fisher J, Chersich M, Luchters S. Attitudes and behaviours of maternal health care providers in interactions with clients: a systematic review. Global Health. 2015;11:36.

doi:10.1186/s12992-015-0117-9 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Govender D, Taylor M, Naidoo S. Adolescent pregnancy and parenting: perceptions of healthcare providers. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:1607–1628. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S258576 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Pampati S, Liddon N, Dittus PJ, Hocevar Adkins S, Steiner RJ. Confidentiality matters but how do we improve implementation in adolescent sexual and reproductive health care? J Adolesc Health. 2019;65(3):315-322. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.03.021 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Haddaway NR, Page MJ, Pritchard CC, McGuinness LA. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and open synthesis. Campbell Syst Rev. 2022;18. doi:10.1002/cl2.1230 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

Not Applicable

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Olayinka Olutade-Babatunde

Department of Nursing

University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Benin City, Edo-State, Nigeria

Email: shindybabz@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Anke van der Kwaak

Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights

KIT Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Bet-ini- N. Christian

Department of Clinical Services

Hospital Management Board, Uyo, Akwa-Ibom State, Nigeria

Maryam I. Keshinro

Department of Public Health

State House Medical Centre, Abuja, Nigeria

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Olutade OB, van Der AK, Bet-ini NC, Maryam IK. A Critical Review of Factors Affecting Health-Seeking Behavior Among Adolescent Mothers in Nigeria: Towards Inclusive and Targeted Interventions. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622420. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622420 Crossref