Author Affiliations

Abstract

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) is an inherited myocardial disease; the hallmark of which is progressive fibro-fatty replacement of the myocardium. The predominant clinical presentation is ventricular arrhythmia. It is a major cause of sudden cardiac death in the young. We presented a 27-year-old male patient from Addis Ababa who presented with dyspnea and palpitation of 2 years duration and a history of syncope during physical exertion. His physical examination and basic laboratory tests were unremarkable. His electrocardiogram (ECG) showed deep T wave inversion in leads V1-V4 with a slurred S wave in these leads. Echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) showed a dilated right ventricle (RV) with RV systolic dysfunction. The CMR also showed diffuse RV wall hypokinesis and mild RV apex dyskinesia. With a definite diagnosis of ARVC, the patient was started on bisoprolol and put on follow-up at the cardiac clinic with strict advice on exercise restriction.

Keywords

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, Fibro fatty replacement, Ventricular arrhythmia, Inherited myocardial disease, Sudden cardiac death.

Introduction

ARVC is an inherited condition characterized by fibro-fatty degeneration of the myocardium.[1] The fibro fatty replacement can be partial or total, and it is due to the mutation of genes encoding desmosomal proteins.[2,3] The most common inheritance pattern is autosomal dominant with variable penetrance.[4] It usually involves the right ventricular myocardium, but the left ventricle can also be involved.[5] The predominant clinical presentation is documented or symptomatic ventricular arrhythmia. Sudden cardiac death can occur at any phase in the course of the disease.[3,6] The prevalence of ARVC ranges from 1 in 2000 to 1 in 500of the population.[4-6] It has a male preponderance with a male-to-female ratio of 2.7:1, and the mean age at presentation is 30 years.[4,5]

Case Presentation

Our case is a 27-year-old male patient from Addis Ababa who presented with exertional dyspnea of two years duration associated with intermittent Palpitation. He had a history of one episode of syncope 18 months back, which occurred while pushing a heavy object. He also had a history of nonspecific chest pain, which is non-radiating and has no improvement with rest when it occurs during exertion.

He is a non-alcoholic and a nonsmoker. He has no chronic cough; He has no orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND) or leg swelling; He has no recreational drug use history; He has no known medical or surgical comorbidity. There is no family history of cardiac illness or sudden death. He is a well-looking young man. Blood pressure (BP) 110/70mmHg, pulse rate (PR) 100 bpm (beats per minute) regular, respiratory rate (RR) 20 breaths/min, SPO2 92%, temperature 36.3 °C. The chest was resonant on percussion with good air entry on auscultation; no finger clubbing. His cardiovascular examination was also unremarkable.

His basic laboratory tests included white blood cell (WBC) 7.1k/mcL (65.3% neutrophil, 26.5%lymphocyte), hemoglobin 18g/dL (hematocrit 51.7%), platelet count 380k/mcL; creatinine 0.67mg/dl, urea 29mg/dl, sodium 140mmol/L, potassium 3.79mmol/L, chloride 98mmol/L, ionized calcium 1.19mmol/L. His echocardiography (Figure 1) showed dilated RV (basal diameter 49mm) and right atrium (RA minor dimension 47mm), dilated main pulmonary artery (MPA) (26mm), tricuspid regurgitation velocity (TRV) 3.6m/sec; concluded as severe pulmonary hypertension (right ventricular systolic pressure/pulmonary artery systolic pressure (RVSP/PASP) 65mmHg), RV systolic dysfunction (TAPSE 14mm, RV fractional area change (FAC) 17%) but normal left ventricular function (LVEF 65%).

Figure 1: 4-chamber view echocardiography with right-sided chamber dilatation

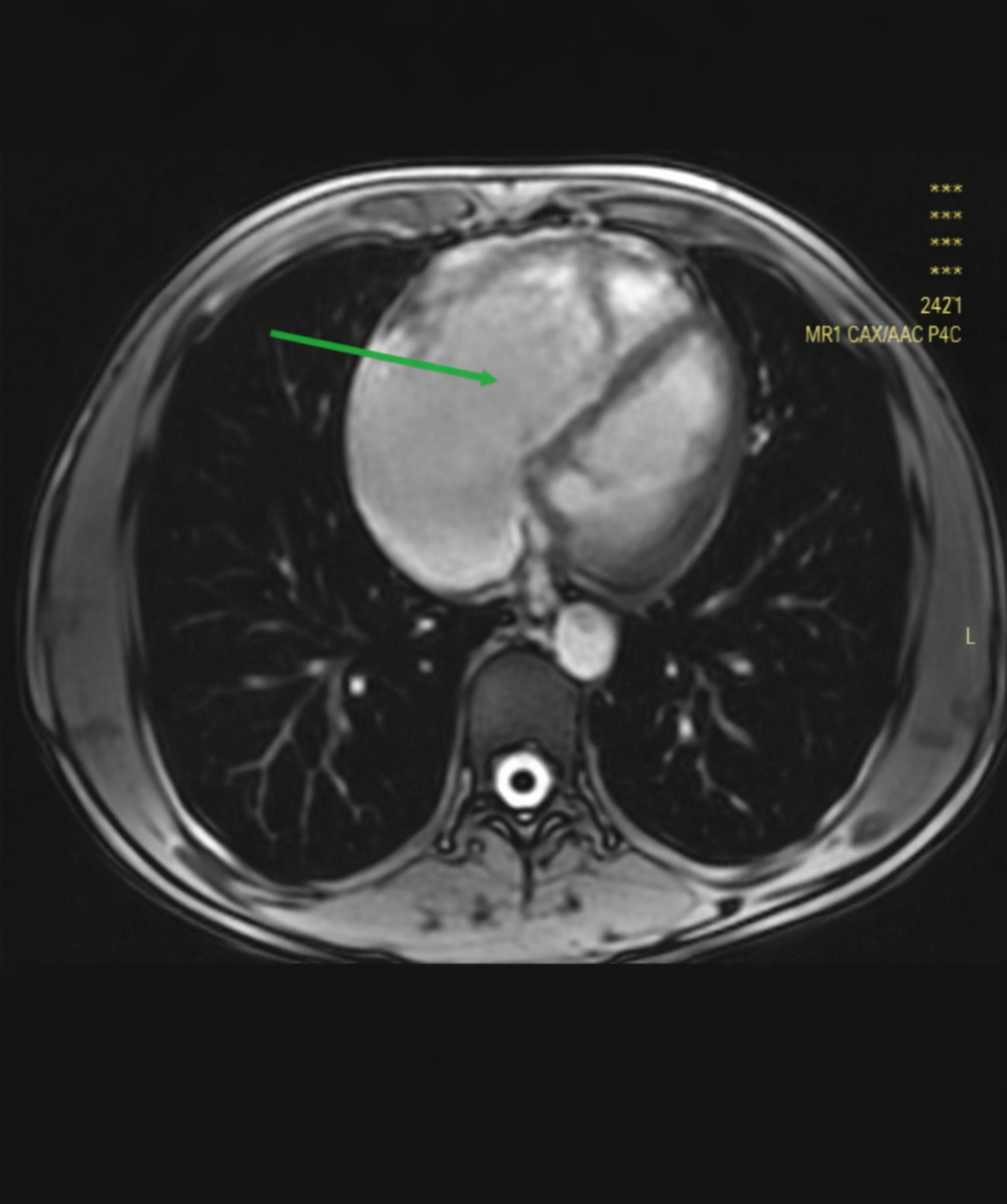

Figure 2: CMR-axial scout cine image of the chest shows markedly dilated right heart chamber as indicated by the solid arrow

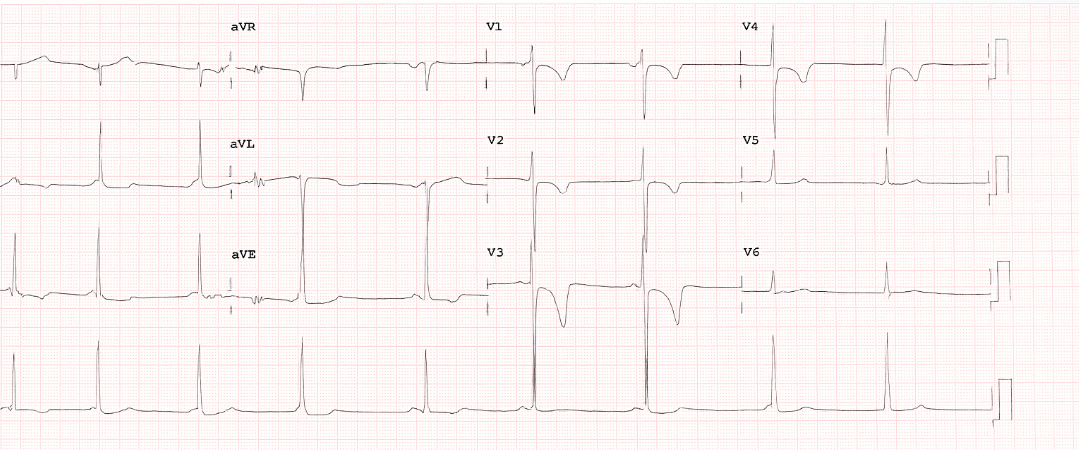

Figure 3: T wave inversion in precordial leads V1, V2, V3, and V4 with terminal activation duration of 60 millisecond classic for ARVC

High resolution chest CT (HRCT) showed bilateral upper lung and parahailar areas of ground glass opacity possibly suggesting atypical pneumonia which was treated. There was no evidence of acute or chronic pulmonary embolism on CT pulmonary angiogram. Pulmonary function tests, including diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO), were normal. These tests were done because the first impression was idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. 24-hour Holter monitoring showed occasional atrial and ventricular ectopies with intermittent junctional escape rhythm, but no ventricular or atrial tachyarrhythmias were seen during the study.

CMR (Figure 2) showed diffuse RV wall hypokinesis, mild RV apex dyskinesia with right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF) 43%. The RV was dilated and hypertrophied; the ratio of RV end diastolic volume to body surface area (RV-EDV/BSA) was 125 milliliters/meter square. Fibro fatty infiltration or late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) was not seen during the study. LVEF was 50%; interventricular septal thickness was normal.

Case Management

The treatment of ARVC includes exercise restriction, implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) insertion, anti-arrhythmic drug use, and catheter ablation during an electrophysiological study, among others, as stipulated by international society guidelines. ICD is inserted in selected patients for secondary or primary prevention of major arrhythmic events, including sudden cardiac death. Our patient had intermediate risk for major arrhythmic events, and the indication for ICD insertion was soft for this index case; as such, ICD was not inserted.[6,7]

Beta blockers are indicated for patients with ventricular ectopies, non-sustained or sustained ventricular tachycardias.[8] Our patient was started on bisoprolol with the aim of preventing symptomatic ventricular arrhythmias. The patient was advised against engagement in competitive sports or frequent high-intensity physical activity, because vigorous exercise is associated with increased occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias and promotes progression of structural disease.[9,10]

Discussion

Despite its rarity, ARVC is a common cause of sudden cardiac death in young adults below the age of 35.[5] It accounts for 11% of sudden cardiac deaths in the general population and up to 22% in athletes.[6] Patients can be asymptomatic for decades; when symptoms are present, palpitation is the most common symptom (27%-64%), and it reflects underlying ventricular arrhythmia. Other symptoms include syncope (26%-32%), atypical chest pain (27%), and dyspnea (11%). The classic presentation is exertional dyspnea and palpitation.[5] Our patient had all these symptoms.

ARVC is diagnosed according to the more inclusive 2020 international criteria, also called the Padua criteria, which were put forward from the revised international task force 2010 criteria.[5,7] According to the Padua criteria, a set of 6 parameters is included, each with major and minor criteria differentiation based on specificity for ARVC diagnosis.[8] These parameters include Morpho-functional ventricular abnormalities, Structural myocardial abnormalities, ECG repolarization abnormalities, ECG depolarization abnormalities, Ventricular arrhythmias, Family history, and genetic testing. The Padua criteria have two sets of criteria for right ventricular dominant (ARVC) and left ventricular dominant (ALVC) phenotypes. Here we see some details of the criteria for ARVC pertaining to our patient as follows.

Morpho-functional ventricular abnormalities: It is assessed by echocardiography, cardiac MRI, or angiography, including Ventricular dilation, Ventricular dysfunction, and Ventricular wall motion abnormality. Any degree of RV dilatation or RV dysfunction with RV wall motion abnormality is a major criterion of ARVC.[8] Our patient has RV dilatation and RV systolic dysfunction on both echocardiography and CMR in the presence of diffuse and apical wall motion abnormality on CMR and hence fulfills one major criterion in this category.

Structural myocardial abnormalities: Mean fibrous or fibro-fatty replacement of the myocardium, which is the hallmark of ACM. It is evaluated with endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) or CMR. Demonstration of fibrous replacement of the RV myocardium in at least 1 sample, with or without fatty tissue, is a major criterion. The presence of transmural late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) in at least 1 RV segment, confirmed in 2 orthogonal views, is a major criterion. The role of EMB for the diagnosis of ARVC is limited due to its invasive nature and low sensitivity.[8] CMR has emerged as the imaging modality of choice in ARVC, allowing for non-invasive morphological and functional evaluation as well as tissue characterization in a single investigation.[7] EMB was not done in our patient, and there was no LGE seen on the CMR.

ECG repolarization abnormalities: in ARVC are reflected by T wave inversion in right precordial leads (V1-V3). T wave inversion in V1-V3 or beyond in the absence of right bundle branch block (RBBB) in individuals with complete pubertal development is a major criterion for ARVC. Our patient has T wave inversion in leads V1-V4, again fulfilling one more major criterion in this category. Extension of the T wave inversion beyond V3 reflects severe RV dilatation, as is seen in our patient.[8]

ECG depolarization abnormalities: Include Epsilon wave in v1-v3, terminal activation duration (TAD)>55msec in the absence of RBBB in v1-v3. These two are minor criteria for ARVC diagnosis.[8] The ECG in our patient (Figure 3) has a terminal activation duration of 60 milliseconds, which fulfills minor criteria.

Ventricular arrhythmias: include premature ventricular beats, ventricular tachycardia of RV origin, which is the most common arrhythmia in ARVC. These ventricular arrhythmias can be detected and documented using standard surface ECG, holter monitoring, or exercise ECG and reflect clinically with palpitation, syncope, or sudden cardiac death. Frequent ventricular extrasystoles (>500 per 24 h), non-sustained or sustained ventricular tachycardia of LBBB morphology.[8] Even though no ventricular arrhythmias were documented on surface ECG or during 24-hour Holter monitoring in our patient, his symptoms can reflect an undetected ventricular arrhythmia.

Family history and genetic testing: Genetic testing is recommended in patients with a definite biventricular or ARVC diagnosis in order to apply mutation-specific cascade genetic testing to identify gene carriers in the families of the proband.[8] Family history was negative, and genetic testing was pending in our case because the test was not available in our local laboratories.

Our case with two major criteria fulfills the diagnosis of definite ARV: He has RV dilatation and RV systolic dysfunction in the presence of diffuse RV hypokinesis and apical RV dyskinesis from morpho-functional abnormality; he has T wave inversion in V1-V4 (Figure 3) from repolarization abnormality.

Conclusion

Our case showed that ARVC is still diagnosed in the absence of documented ventricular arrhythmias, provided that diagnostic criteria are fulfilled in patients who have symptoms suggestive of arrhythmia.

References

- Latt H, Tun Aung T, Roongsritong C, Smith D. A classic case of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) and literature review. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2017;7(2):115-121. doi:10.1080/20009666.2017.1302703 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Khan Z, Rayner T, Sethumadhavan D, Hamid S. A Case Report of a Young Patient Presenting With Syncope Secondary to Arrhythmogenic Ventricular Cardiomyopathy. Cureus. 2023;15(1):e33731. doi:10.7759/cureus.33731 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kuwabara K, Hirata K, Wake M, et al. A case of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy presenting with progressive right ventricular failure and recurrent multifocal monomorphic ventricular tachycardia during 15 years of follow-up. J Cardiol Cases. 2014;10(6):216-220. doi:10.1016/j.jccase.2014.07.014 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Sitwala P, Ladia V. Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy: A Case Presentation with a Review. Int J Cardiovasc Res. 2015;4. doi:10.4172/2324-8602.1000239 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Aiwuyo HO, Javed G, Ataiyero O, et al. Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy: A Review of a Rare Case of Biventricular Phenotype. Cureus. 2022;14(10):e30040. doi:10.7759/cureus.30040 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Elias Neto J, Tonet J, Frank R, Fontaine G. Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia (ARVC/D) – What We Have Learned after 40 Years of the Diagnosis of This Clinical Entity. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019;112(1):91-103. doi:10.5935/abc.20180266 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- te Riele AS, Tandri H, Bluemke DA. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC): cardiovascular magnetic resonance update. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2014;16(1):50. doi:10.1186/s12968-014-0050-8 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Corrado D, Perazzolo Marra M, Zorzi A, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy: The Padua criteria. Int J Cardiol. 2020;319:106-114. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.06.005 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Towbin JA, McKenna WJ, Abrams DJ, et al. 2019 HRS expert consensus statement on evaluation, risk stratification, and management of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16(11):e301-372. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2019.05.007 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Arbelo E, Protonotarios A, Gimeno JR, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(37):3503-3626. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehad194 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our gratitude to the patient for allowing his own case to be educational.

Funding

There is no source of funding for this manuscript.

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Habtamu Gebeyehu Jenbere

Department of Internal Medicine

Saint Paul Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Email: doctorhabtamugjenberei@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Alebachew Girum, Seifu Bacha, Fitsum Negusse Assefa

Department of Internal Medicine

Saint Paul Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Kibrom Mulugeta

Department of Internal Medicine

MeQrez General Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Mekonen Birhanu

Department of Radiology

Saint Paul Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed equally to conceiving the idea, acquiring the data, writing the manuscript, and reviewing the literature.

Ethical Approval

Ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional review board (IRB) of St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College (Ref. No: PM23/727; Protocol No: SPHMCC-ERC-144/25).

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and the document has been submitted to the journal with the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Guarantor

The guarantor of this case report is the corresponding author who ensures the accuracy and integrity of the content presented.

DOI

Cite this Article

Girum A, Jenbere HG, Mulugeta K, Bacha S, Birhanu M, Assefa FN. A Case of Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy with Symptomatic Arrhythmia. medtigo J Med. 2025;3(2):e30623230. doi:10.63096/medtigo30623230 Crossref